In 1993, the early days of the web saw only about 14 million users and 100 websites. While webpages were static, there was a growing demand for dynamic content, such as real-time news and data. To meet this need, Rob McCool and other developers created the Common Gateway Interface (CGI) within the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) HTTPd web server (which later evolved into Apache). This marked the first instance of a web server capable of delivering content generated by an external application.

Since then, the internet has witnessed an explosion in user numbers, making dynamic websites commonplace. Developers, even those new to coding or a specific language, are often eager to learn how to integrate their code with the web.

Python’s Web Journey and the Emergence of WSGI

The landscape has shifted dramatically since CGI’s inception. The CGI method, which spawned a new process for every request, proved inefficient, consuming excessive memory and CPU resources. Subsequently, alternative low-level approaches like FastCGI](http://www.fastcgi.com/) (1996) and mod_python (2000) emerged, offering different ways for Python web frameworks to interact with web servers. This proliferation of approaches created a compatibility issue, where the choice of framework limited web server options, and vice versa.

To address this challenge, Phillip J. Eby proposed PEP-0333, the Python Web Server Gateway Interface (WSGI), in 2003. The aim was to establish a high-level, standardized interface between Python applications and web servers.

In the same year, PEP-3333](https://peps.python.org/pep-3333/) introduced updates to the WSGI interface, adding support for Python 3. Today, WSGI has become the primary, if not the sole, method for nearly all Python frameworks to communicate with their web servers. This is the approach adopted by frameworks like Django, Flask, and numerous others.

This article aims to provide readers with a basic understanding of WSGI’s workings and guide them in building a simple WSGI application or server. However, it is not meant to be comprehensive, and developers aiming to create production-ready servers or applications are encouraged to delve deeper into the WSGI specification.

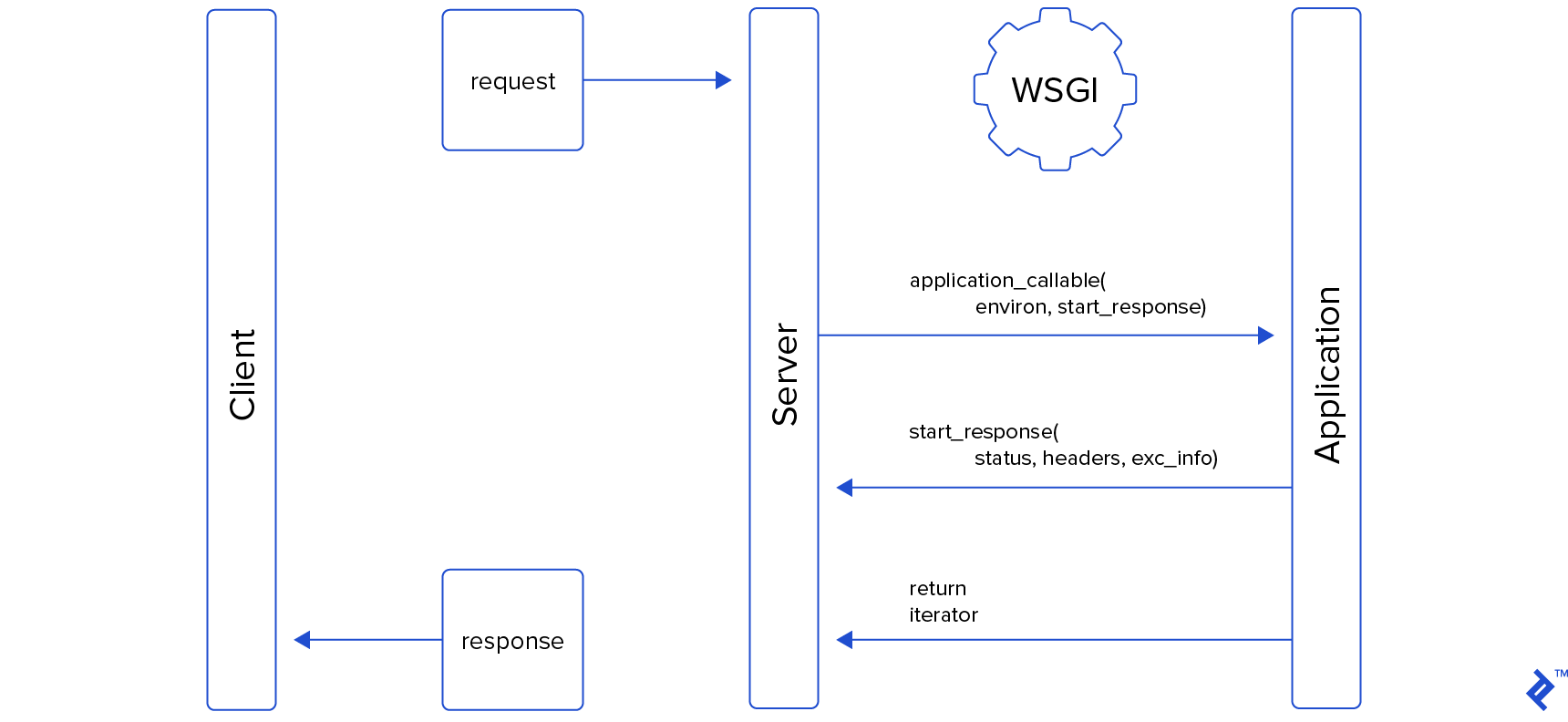

Demystifying the Python WSGI Interface

WSGI establishes straightforward guidelines that both servers and applications must adhere to. Let’s start by examining this general pattern.

Application Interface

In Python 3.5, the application interface is structured as follows:

| |

In Python 2.7, the interface remains largely similar; the sole difference is that the body is represented as a str object instead of a bytes object.

While we’ve used a function in this example, any callable is suitable. The rules governing the application object are as follows:

- It must be callable, accepting

environandstart_responseas parameters. - It must invoke the

start_responsecallback before transmitting the body. - It must return an iterable comprising parts of the document body.

Here’s another example of an object that fulfills these rules and produces the same result:

| |

Server Interface

A WSGI server might interact with this application like this:

| |

You might have noticed that the start_response callable returned a write callable, which the application can use to send data back to the client. However, our example application code didn’t utilize this feature. This write interface is deprecated and can be disregarded for now; it will be briefly touched upon later in the article.

Another responsibility of the server is to call the optional close method on the response iterator, if it exists. As highlighted in Graham Dumpleton’s article here, this is a frequently overlooked aspect of WSGI. Calling this method, if present, enables the application to release any resources it might still be holding.

Unveiling the Application Callable’s environ Argument

The environ parameter takes the form of a dictionary object, serving as a conduit for passing request and server information to the application, much like CGI. In fact, all CGI environment variables are valid in WSGI, and the server is expected to pass all applicable ones to the application.

While numerous optional keys can be passed, some are mandatory. Consider the following GET request as an example:

| |

Here are the mandatory keys that the server must provide, along with the values they would assume:

| Key | Value | Comments |

|---|---|---|

REQUEST_METHOD | "GET" | |

SCRIPT_NAME | "" | server setup dependent |

PATH_INFO | "/auth" | |

QUERY_STRING | "token=123" | |

CONTENT_TYPE | "" | |

CONTENT_LENGTH | "" | |

SERVER_NAME | "127.0.0.1" | server setup dependent |

SERVER_PORT | "8000" | |

SERVER_PROTOCOL | "HTTP/1.1" | |

HTTP_(...) | Client supplied HTTP headers | |

wsgi.version | (1, 0) | tuple with WSGI version |

wsgi.url_scheme | "http" | |

wsgi.input | File-like object | |

wsgi.errors | File-like object | |

wsgi.multithread | False | True if server is multithreaded |

wsgi.multiprocess | False | True if server runs multiple processes |

wsgi.run_once | False | True if the server expects this script to run only once (e.g.: in a CGI environment) |

It’s worth noting that if any of these keys are empty (like CONTENT_TYPE in the table above), they can be omitted from the dictionary. In such cases, it’s assumed that they correspond to an empty string.

wsgi.input and wsgi.errors

Most environ keys are self-explanatory, but two warrant further clarification: wsgi.input and wsgi.errors. The former houses a stream containing the request body from the client, while the latter serves as a channel for the application to report any encountered errors. Errors relayed from the application to wsgi.errors typically end up in the server’s error log.

These keys must contain file-like objects, meaning objects that offer interfaces for reading from or writing to streams, similar to how we interact with files or sockets in Python. While this might seem intricate initially, Python provides convenient tools for handling this.

Firstly, what kind of streams are we dealing with? As per the WSGI definition, wsgi.input and wsgi.errors must handle bytes objects in Python 3 and str objects in Python 2. In either case, if we want to use an in-memory buffer for passing or receiving data through the WSGI interface, we can employ the io.BytesIO class.

For instance, if we’re developing a WSGI server, we could provide the request body to the application as follows:

- For Python 2.7:

| |

- For Python 3.5:

| |

From the application’s perspective, if we want to convert a received stream input into a string, we would do something like this:

- For Python 2.7:

| |

- For Python 3.5:

| |

The wsgi.errors stream should be used to communicate application errors to the server, with lines terminated by a \n character. It’s the web server’s responsibility to handle the conversion to a different line ending based on the system.

Understanding the Application Callable’s start_response Argument

The start_response argument must be a callable that accepts two required arguments: status and headers, and one optional argument: exc_info. The application must call this callable before transmitting any part of the body back to the web server.

In the initial application example at the beginning of this article, we returned the response body as a list, giving us no control over when the list would be iterated over. Consequently, we had to call start_response before returning the list.

In the second example, we called start_response just before yielding the first (and in this case, only) piece of the response body. Both approaches are valid within the WSGI specification.

From the web server’s standpoint, invoking start_response shouldn’t immediately send the headers to the client. Instead, it should delay this until there’s at least one non-empty bytestring in the response body ready to be sent to the client. This architecture ensures that errors can be reported correctly until the very last moment of the application’s execution.

Examining the status Argument of start_response

The status argument passed to the start_response callback must be a string consisting of an HTTP status code and a description, separated by a single space. Valid examples include '200 OK' or '404 Not Found'.

Examining the headers Argument of start_response

The headers argument passed to the start_response callback must be a Python list of tuples, with each tuple structured as (header_name, header_value). Both the name and value of each header must be strings, regardless of the Python version. This is a rare instance where type enforcement is crucial, as mandated by the WSGI specification.

Here’s a valid example of what a header argument might look like:

| |

HTTP headers are case-insensitive, which is something to keep in mind when writing a WSGI-compliant web server and handling these headers. Moreover, the list of headers provided by the application isn’t expected to be exhaustive. The server is responsible for ensuring that all required HTTP headers are present before sending the response back to the client, filling in any headers omitted by the application.

Examining the exc_info Argument of start_response

The start_response callback should support a third argument, exc_info, used for error handling. The proper usage and implementation of this argument are paramount for production-ready web servers and applications but fall outside this article’s scope.

You can find more information on this in the WSGI specification, here.

Understanding the start_response Return Value – The write Callback

For backward compatibility, web servers implementing WSGI should return a write callable. This callback allows the application to write response body data directly to the client, bypassing the iterator-based yielding mechanism.

Despite its existence, this is a deprecated interface, and new applications should avoid using it.

Generating the Response Body

Applications implementing WSGI should generate the response body by returning an iterable object. In most cases, the response body is relatively small and fits comfortably within the server’s memory. In such scenarios, the most efficient approach is to send it all at once using a one-element iterable. However, in situations where loading the entire body into memory is impractical, the application can return it in parts through this iterable interface.

There’s a minor difference between Python 2’s and Python 3’s WSGI implementations: in Python 3, the response body is represented by bytes objects, while in Python 2, the correct type is str.

Converting UTF-8 strings into bytes or str is straightforward:

- Python 3.5:

| |

- Python 2.7:

| |

If you’re interested in learning more about handling Unicode and bytestrings in Python 2, there’s an excellent tutorial on YouTube.

Web servers implementing WSGI should also support the write callback for backward compatibility, as previously mentioned.

Testing Applications Without a Web Server

Armed with an understanding of this simple interface, we can effortlessly create scripts to test our applications without needing to launch an actual server.

Consider this small script, for example:

| |

This allows us to, for instance, initialize some test data and mock modules within our application and make GET calls to verify if it responds as expected. It’s evident that this isn’t a real web server; instead, it interacts with our application in a comparable manner by providing the application with a start_response callback and a dictionary containing our environment variables. Upon request completion, it consumes the response body iterator and returns a string with its entire content. Similar methods (or a more generic one) can be created for different HTTP request types.

In Conclusion

This article doesn’t cover how WSGI handles file uploads, as this is considered a more advanced topic not suitable for an introductory piece. If you’d like to learn more about it, take a look at the PEP-3333 section referring to file handling.

I hope this article helps you better grasp how Python communicates with web servers and empowers you to use this interface in innovative and interesting ways.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to express my gratitude to my editor, Nick McCrea, for his invaluable assistance with this article. His contributions have significantly enhanced the clarity of the original text and prevented several errors from slipping through the cracks.