Our astrophysics simulator is driven by a powerful combination of hope, hype, and access to new computing power.

We achieve this computing power using web workers. If you are already well-versed in web workers, you might want to examine the code and proceed directly to the section on WebAssembly, which is covered in the subsequent article.

JavaScript rose to prominence as the most widely installed, learned, and accessible programming language due to its introduction of groundbreaking features to the static web:

- Single-threaded event loop

- Asynchronous code

- Garbage collection

- Data without rigid typing

Single-threaded execution eliminates concerns about the complexities and challenges of multithreaded programming.

Asynchronous code allows us to use functions as parameters that can be executed later as events within the event loop.

These features, along with Google’s significant investments in enhancing the performance of Chrome’s V8 JavaScript engine and the availability of robust developer tools, have established JavaScript and Node.js as the ideal options for microservice architectures.

Single-threaded execution is also advantageous for browser developers, who are tasked with securely isolating and running multiple browser tab runtimes, often laden with spyware, across various cores of a computer.

Question: How can a single browser tab utilize all the CPU cores of your computer? Answer: Web workers!

Web Workers and Threading

Web workers utilize the event loop to exchange messages asynchronously between threads, effectively circumventing many potential issues associated with multithreaded programming.

Furthermore, web workers can offload computations from the main UI thread, allowing it to focus on handling user interactions like clicks and animations, as well as managing the DOM.

Let’s examine some code snippets from the project’s GitHub repo.

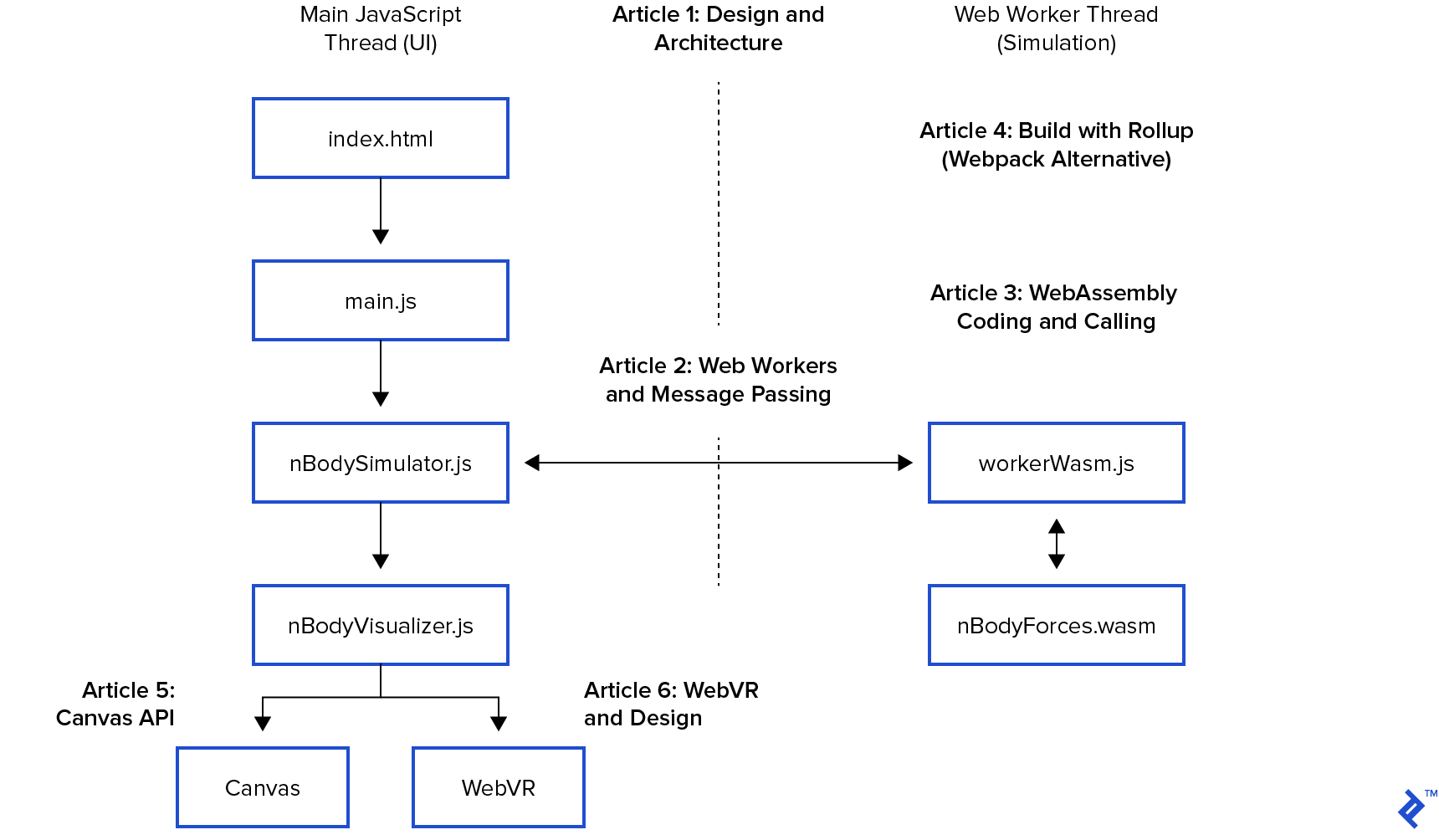

As per our architecture diagram, we’ve handed over the entire simulation to nBodySimulator, which is responsible for managing the web worker.

Recall from the introductory post that nBodySimulator has a step() function that’s called every 33ms during the simulation. This function invokes calculateForces(), updates positions, and redraws the simulation.

| |

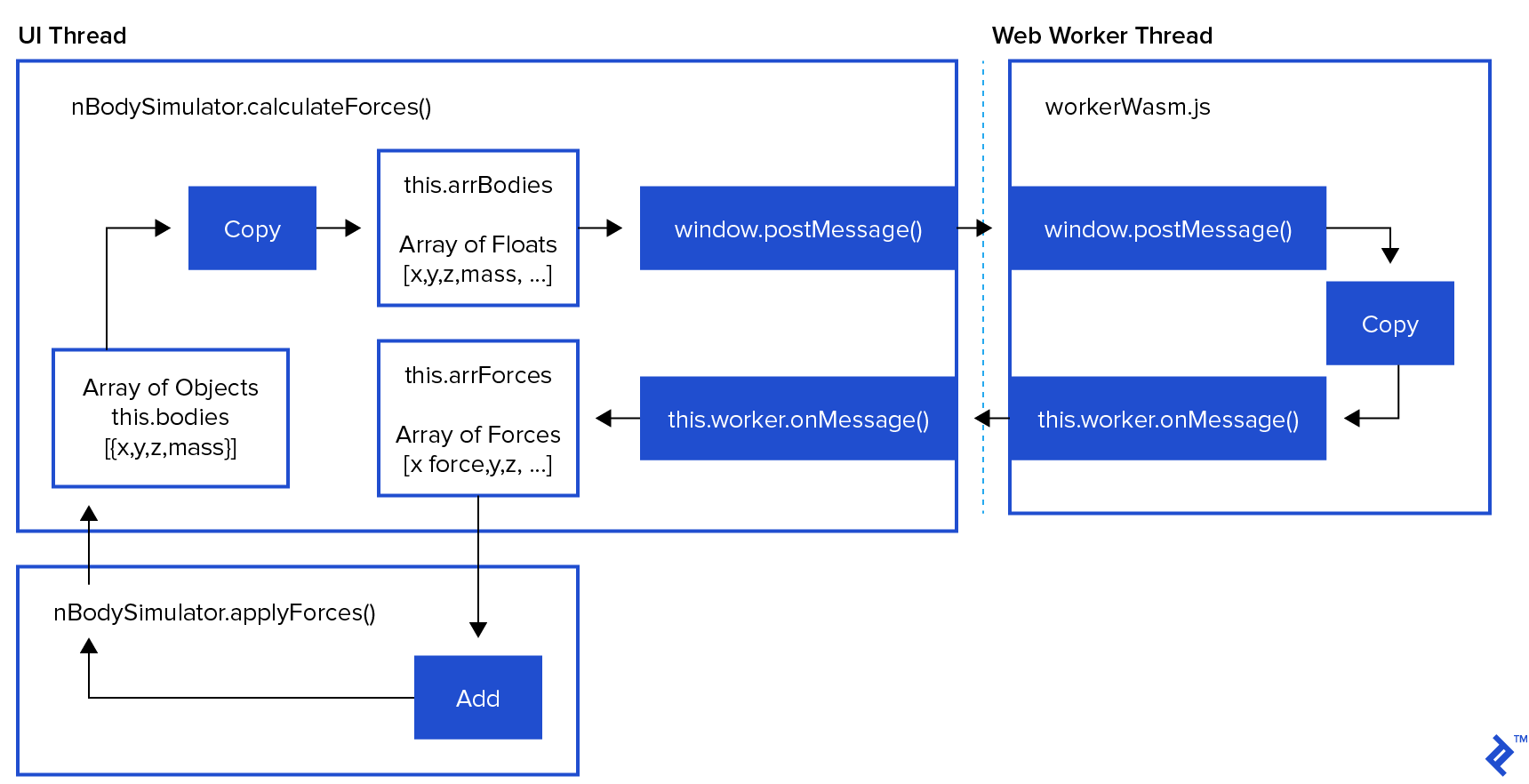

The web worker’s role is to provide a dedicated thread for WebAssembly. Being a low-level language, WebAssembly only works with integers and floats. We cannot directly pass JavaScript Strings or Objects to it; instead, we use pointers to “linear memory.” For simplicity, we package our “bodies” into an array of floats called arrBodies.

We will delve deeper into this aspect in the article dedicated to WebAssembly and AssemblyScript.

In this section, we are creating a web worker to execute calculateForces() in a separate thread. This is accomplished by first converting the bodies’ properties (x, y, z, mass) into an array of floats called arrBodies. Then, we use this.worker.postMessage() to send this array to the worker. Finally, we return a promise that the worker will resolve later in this.worker.onMessage().

| |

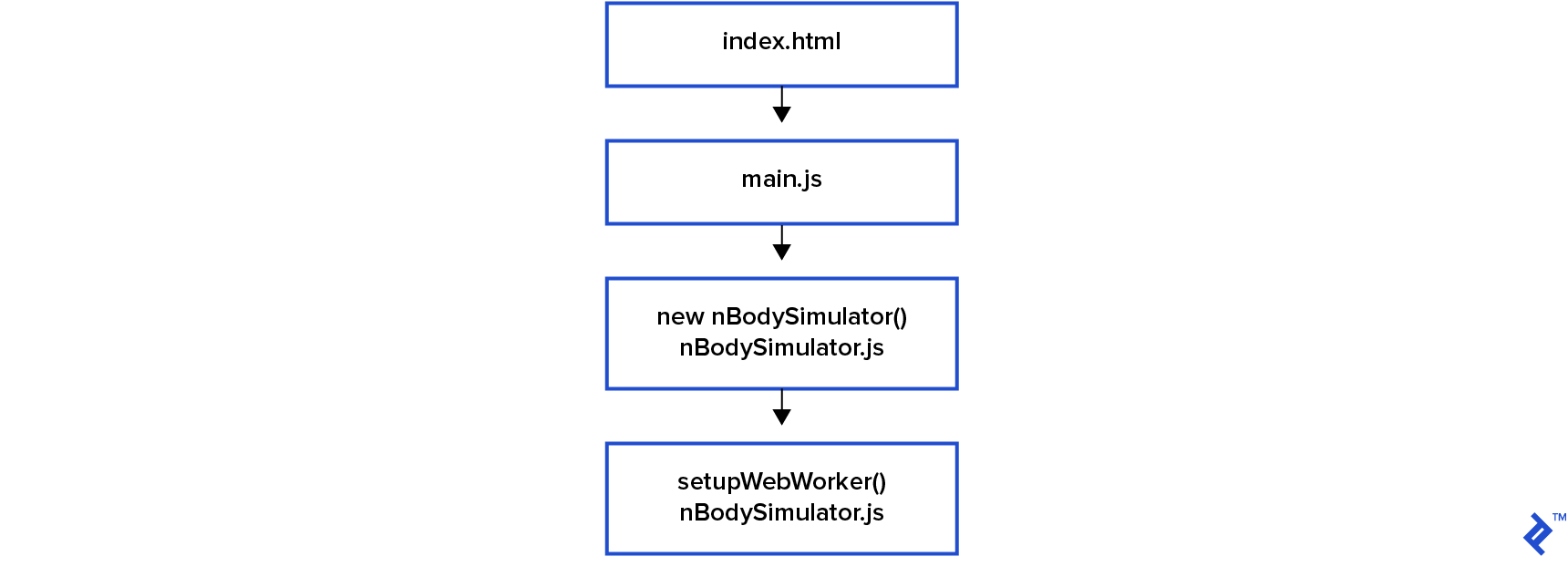

The process begins with the browser sending a GET request to retrieve index.html, which then executes main.js. This, in turn, creates a new nBodySimulator(). Within its constructor, we find setupWebWorker().

| |

Our new nBodySimulator() instance resides in the main UI thread, and the setupWebWorker() function is responsible for creating the web worker by fetching workerWasm.js from the network.

| |

When new Worker() is executed, the browser retrieves and runs workerWasm.js within a separate JavaScript runtime (and thread) and initiates message passing.

Next, workerWasm.js delves into the intricacies of WebAssembly, essentially boiling down to a single this.onmessage() function with a switch() statement.

It’s important to remember that web workers lack direct network access. Therefore, the main UI thread must deliver the compiled WebAssembly code to the web worker as a message, resolving it as resolve("action packed"). We’ll explore this process in detail in the following post.

| |

Returning to the setupWebWorker() method within our nBodySimulation class, we handle messages from the web worker using a familiar onmessage() + switch() pattern.

| |

In this particular instance, calculateForces() creates and returns a promise, storing resolve() and reject() as self.forcesReject() and self.forcesResolve(), respectively.

This setup allows worker.onmessage() to resolve the promise that was initially created in calculateForces().

Recall the step() function from our simulation loop:

| |

This allows us to bypass calculateForces() and reuse the previous forces in case WebAssembly is still occupied with calculations.

This step function executes every 33ms. If the web worker isn’t ready, it proceeds to apply and render the previous forces. In situations where a particular step’s calculateForces() calculation extends beyond the beginning of the next step, the subsequent step will utilize forces calculated based on the position from the previous step. These previous forces are either sufficiently similar to appear “correct” or occur at such a rapid pace that they are imperceptible to the user. This trade-off effectively enhances the perceived performance, even though it might not be suitable for actual human space travel.

Can this be further enhanced? Absolutely! An alternative to employing setInterval for our step function is requestAnimationFrame().

For my current objectives, this implementation is adequate for exploring Canvas, WebVR, and WebAssembly. Feel free to provide feedback or reach out if you believe there are areas for improvement or modification.

If you’re seeking a comprehensive and modern physics engine design, take a look at the open-source Matter.js.

What About WebAssembly?

WebAssembly is a portable binary format that functions seamlessly across various browsers and operating systems. It can be generated from a multitude of languages, including C/C++, Rust, and others. For my personal project, I opted to experiment with AssemblyScript, a language built upon TypeScript, which itself is an extension of JavaScript. This choice was motivated by its turtles all the way down.

AssemblyScript compiles TypeScript code into a portable “object code” binary format, allowing for just-in-time compilation into a new, high-performance runtime environment known as Wasm. During the compilation of TypeScript into the .wasm binary, it’s also possible to generate a human-readable .wat “web assembly text” format that provides a representation of the binary code.

The concluding part of setupWebWorker() sets the stage for our next article on WebAssembly and demonstrates how to circumvent web workers’ limitations regarding network access. We fetch the wasm file in the main UI thread and then employ just-in-time compilation to transform it into a native Wasm module. This module is then sent to the web worker via postMessage():

| |

Subsequently, workerWasm.js instantiates this module, granting us the ability to invoke its functions:

| |

This is how we harness the power of WebAssembly. Examining the unredacted source code reveals that the ... represents a series of memory management operations designed to transfer data into dataRef and retrieve results from resultRef. Memory management in JavaScript—how exciting!

In the next installment, we will delve into the intricacies of WebAssembly and AssemblyScript in greater detail.

Execution Boundaries and Shared Memory

Another crucial aspect to address is the concept of execution boundaries and shared memory.

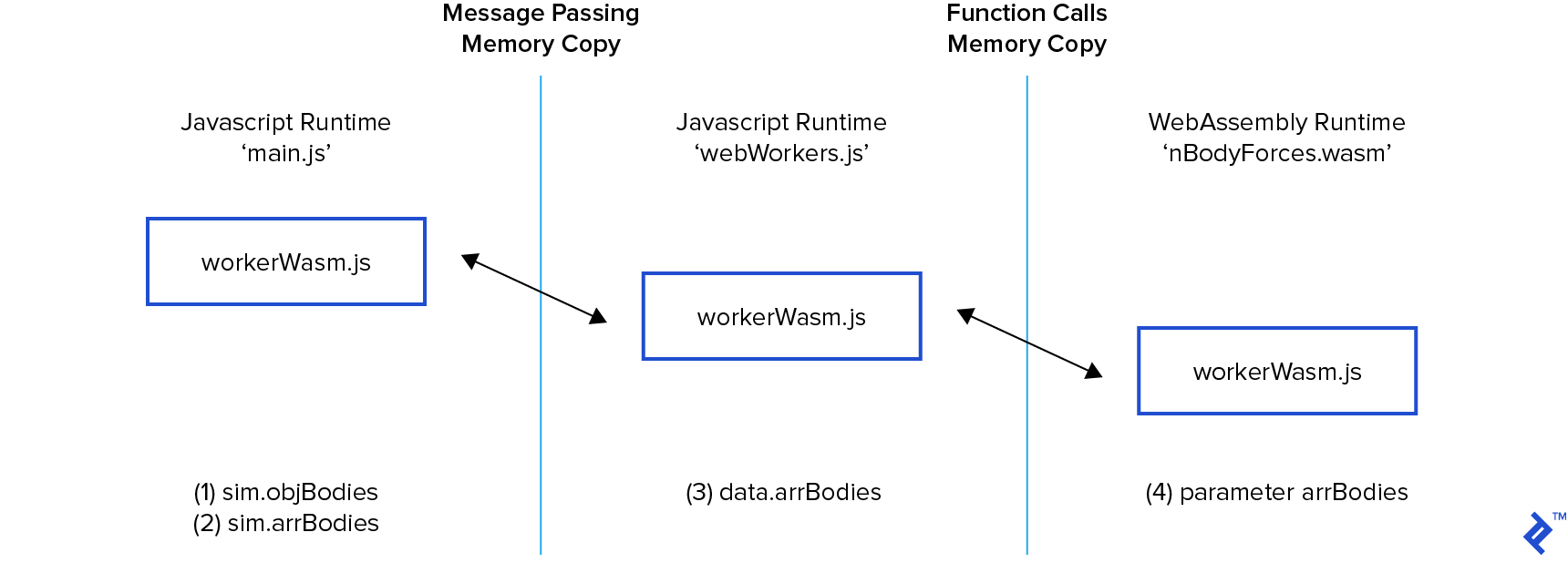

While the WebAssembly article provides a tactical perspective, it’s important to discuss runtimes. Both JavaScript and WebAssembly operate within “emulated” runtimes. In the current implementation, every time we cross a runtime boundary, a copy of our body data (x, y, z, mass) is created. Although memory copying is relatively inexpensive, it’s not the most efficient approach for high-performance scenarios.

Fortunately, a dedicated group of brilliant minds is actively engaged in developing specifications and implementations for these cutting-edge browser technologies.

JavaScript offers SharedArrayBuffer, which enables the creation of shared memory objects. This would effectively eliminate the need to copy data during postMessage() from (2) to (3) during the call and onmessage()’s copying of arrForces from (3) back to (2) when returning the result.

Similarly, WebAssembly has a Linear Memory design in progress that could potentially host a shared memory space for the nBodyForces() call from (3) to (4). Additionally, the web worker could leverage shared memory to handle the result array.

Join us next time as we embark on a captivating exploration of JavaScript memory management.