Domain-driven design (DDD) is not just a technology or a methodology. It offers a set of practices and terms to help make design choices that simplify and speed up software projects, especially those dealing with complex domains. As described by Eric Evans and Martin Fowler have noted, Domain objects are a suitable place for storing validation rules and business logic.

Eric Evans states:

The Domain Layer (or Model Layer) is key to representing business concepts, information about the business situation, and business rules. It manages and uses the state that reflects the business situation, although the technical storage details are handled by the infrastructure. This layer is at the core of business software.

Martin Fowler adds:

The logic within a domain object should be domain logic - validations, calculations, business rules - whatever term you prefer.

However, placing all validation within Domain objects can lead to unwieldy and complicated objects. I believe in separating domain validations into independent validator components that can be reused whenever needed and adapt to the context and user action.

Martin Fowler writes in an insightful article: ContextualValidation.

I frequently observe developers creating validation routines for objects. These routines can take different forms: within the object or external, returning a boolean or throwing an exception to signal failure. However, developers often stumble when they view object validity without considering the context, like an isValid method suggests. […] I believe it’s more helpful to consider validation as something tied to a specific context, usually an action you want to perform. For instance, asking if an order is valid for fulfillment or a customer is valid for hotel check-in. Therefore, instead of methods like isValid, use methods like isValidForCheckIn.

Action Validation Proposal

This article will demonstrate a simple interface, ItemValidator, requiring you to implement a validate method returning a ValidationResult. This object contains the validated item and a Messages object, which gathers errors, warnings, and information validation states (messages) based on the execution context.

Validators are self-contained components, easily reusable wherever needed. This approach allows for the straightforward injection of any dependencies required for validation checks. For instance, validating if a user with a specific email exists in the database would only require the UserDomainService.

Validator separation will be context (action) specific. So, UserCreate and UserUpdate actions will have separate components, and the same applies to other actions (UserActivate, UserDelete, AdCampaignLaunch, etc.). This can lead to a rapid increase in validation components.

Each action validator should have a corresponding action model containing only the permitted fields for that action. For creating users, the necessary fields are:

UserCreateModel:

| |

For updating a user, the allowed fields are externalId, firstName, and lastName. The externalId is used for user identification, and only changes to firstName and lastName are permitted.

UserUpdateModel:

| |

Validations related to field integrity can be shared. For instance, the maximum length for firstName is always 255 characters.

During validation, it is beneficial to gather all encountered issues instead of just the first error. For example, the following three issues could occur simultaneously and should be reported accordingly:

- invalid address format [ERROR]

- email must be unique among users [ERROR]

- password too short [ERROR]

To achieve this, a validation state builder is needed, which is where Messages comes in. I learned about the concept of Messages from a mentor who introduced it for validation and various other purposes, as Messages are not limited to validation.

Note: We will be using Scala to illustrate the implementation in the following sections. Don’t worry if you are not a Scala expert; it should be easy to understand.

Messages in Context Validation

Messages is an object representing the validation state builder. It offers a convenient way to collect error, warning, and information messages during validation. Each Messages object contains a collection of Message objects and can reference a parentMessages object.

A Message object includes the following: type, messageText, key (optional, used to support validation of specific inputs identified by an identifier), and childMessages (enables the creation of composable message trees).

A message can be one of these types:

- Information

- Warning

- Error

Structuring messages in this way allows for iterative building and enables decisions about subsequent actions based on the current message state. For instance, consider validation during user creation:

| |

This code snippet utilizes ValidateUtils, utility functions for populating the Messages object in predefined scenarios. You can examine the implementation of the ValidateUtils on Github code.

During email validation, we first check if the email is valid using ValidateUtils.validateEmail(…, followed by checking its length using ValidateUtils.validateLengthIsLessThanOrEqual(…. Only if both checks pass do we proceed to verify if the email is already assigned to a user using if(!localMessages.hasErrors()) { …. This approach avoids unnecessary database calls. Keep in mind that this is only a part of UserCreateValidator; the complete source code is available here.

Notice the validation parameter UserCreateEntity.EMAIL_FORM_ID. This parameter links the validation state to a specific input ID.

In the previous examples, the next action depends on whether the Messages object contains errors (using the hasErrors method). You could easily check for “WARNING” messages and retry if necessary.

Another notable aspect is the use of localMessages. Local messages are created like any other message but with a parentMessages reference. The goal is to have a reference solely to the current validation state (in this example, emailValidation), allowing the use of localMessages.hasErrors. This checks for errors only within the emailValidation context. Additionally, adding a message to localMessages also adds it to parentMessages, ensuring that all validation messages are present in the higher context of UserCreateValidation.

Having seen Messages in action, let’s focus on ItemValidator in the next section.

ItemValidator - Reusable Validation Component

ItemValidator is a simple trait (interface) that requires developers to implement a validate method returning a ValidationResult.

ItemValidator:

| |

ValidationResult:

| |

By implementing ItemValidators, such as UserCreateValidator, as dependency injection components, you can inject and reuse them in any object requiring UserCreate action validation.

After validation, we check if it was successful. If so, user data is saved to the database; otherwise, an API response containing validation errors is returned.

Next, we will explore how to present validation errors in a RESTful API response and communicate execution action states to API consumers.

Unified API Response - Simple User Interaction

After successfully validating a user action (in this case, user creation), you need to present the results to the RESTful API consumer. The best approach is to use a unified API response, where only the context changes (specifically, the “data” value in JSON). Unified responses facilitate the presentation of errors to API consumers.

Unified response structure:

| |

The unified response has two message tiers: global and local. Local messages are tied to specific inputs (e.g., “username is too long, at most 80 characters allowed”), while global messages reflect the state of the entire page’s data (e.g., “user will not be active until approved”). Both local and global messages have three levels: error, warning, and information. The “data” value is context-specific. When creating users, it contains user data; when retrieving a list of users, it contains an array of users.

This structured response allows for creating a simple client UI handler to display error, warning, and information messages. Global messages are displayed at the top of the page due to their relation to the global API action state, while local messages appear near their corresponding input fields. Error messages are displayed in red, warnings in yellow, and information in blue.

For example, in an AngularJS client app, you could have two directives handling local and global response messages. This ensures consistent handling of all responses.

The local message directive needs to be applied to the parent element of the element holding all the messages.

localmessages.direcitive.js:

| |

The global message directive will be included in the root layout document (index.html) and register for an event to handle all global messages.

globalmessages.directive.js:

| |

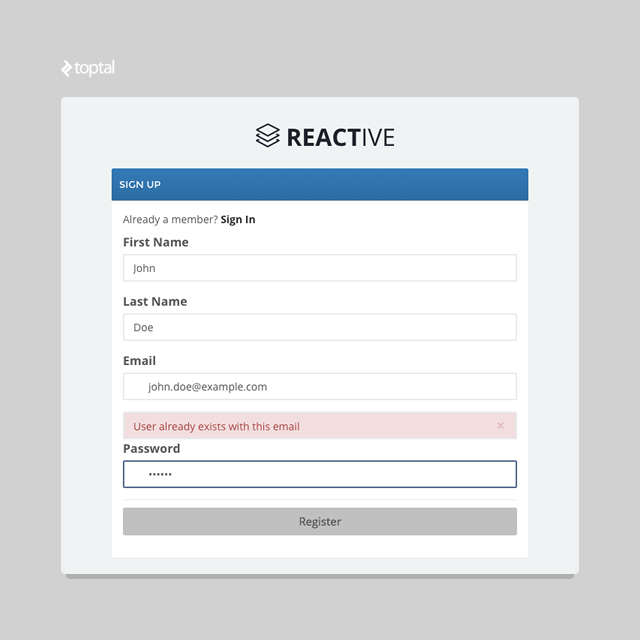

For a clearer illustration, consider the following response containing a local message:

| |

This response could lead to the following:

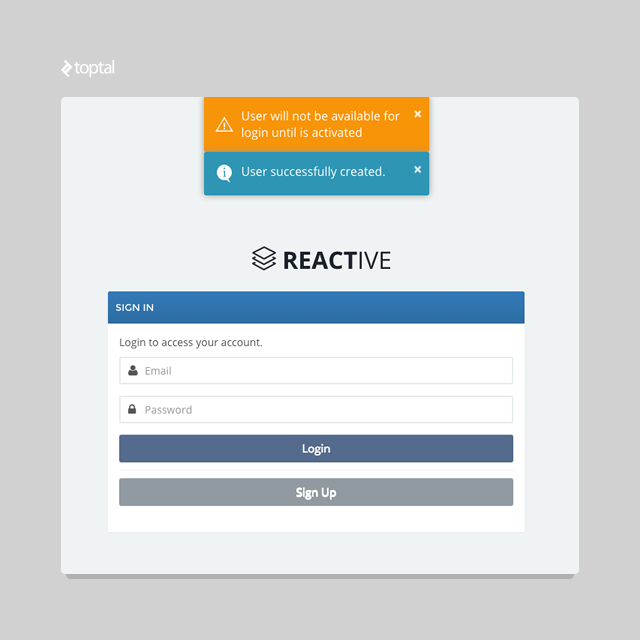

Conversely, consider a response with a global message:

| |

The client app can then display this message with higher prominence:

These examples demonstrate how a unified response structure allows handling different requests with the same handler.

Conclusion

Implementing validation in large projects can easily become disorganized, leading to validation rules scattered throughout the codebase. Maintaining consistent and well-structured validation makes it easier to manage and reuse.

You can find these ideas implemented in two different boilerplate versions:

- Standard Play 2.3, Scala 2.11.1, Slick 2.1, Postgres 9.1, Spring Dependency Injection

- Reactive non-blocking Play 2.4, Scala 2.11.7, Slick 3.0, Postgres 9.4, Guice Dependency Injection

This article presented my suggestions for implementing deep, composable context validation and presenting it to the user effectively. I hope this helps you tackle the challenges of proper validation and error handling. Feel free to leave your comments and share your thoughts below.