This article explores how incorporating declarative programming techniques strategically can help teams build web applications that are simpler to maintain and expand.

“…declarative programming is a programming paradigm that expresses the logic of a computation without describing its control flow.” —Remo H. Jansen, Hands-on Functional Programming with TypeScript

As with many software development decisions, choosing to use declarative programming in your applications requires a careful consideration of the advantages and disadvantages. For a detailed analysis of these tradeoffs, refer to one of our earlier articles.

This article focuses on how to gradually integrate declarative programming patterns into both new and existing JavaScript applications. JavaScript’s support for multiple paradigms makes this integration possible.

We’ll begin by examining how to leverage TypeScript for both front-end and back-end development, enhancing code expressiveness and adaptability to changes. We’ll then delve into finite-state machines (FSMs) as a way to streamline front-end development and involve stakeholders more actively in the process.

FSMs are a mature technology, discovered roughly 50 years ago and widely used in fields like signal processing, aeronautics, and finance, where software reliability is paramount. They’re also highly suitable for modeling common challenges in modern web development, such as managing complex asynchronous state updates and animations.

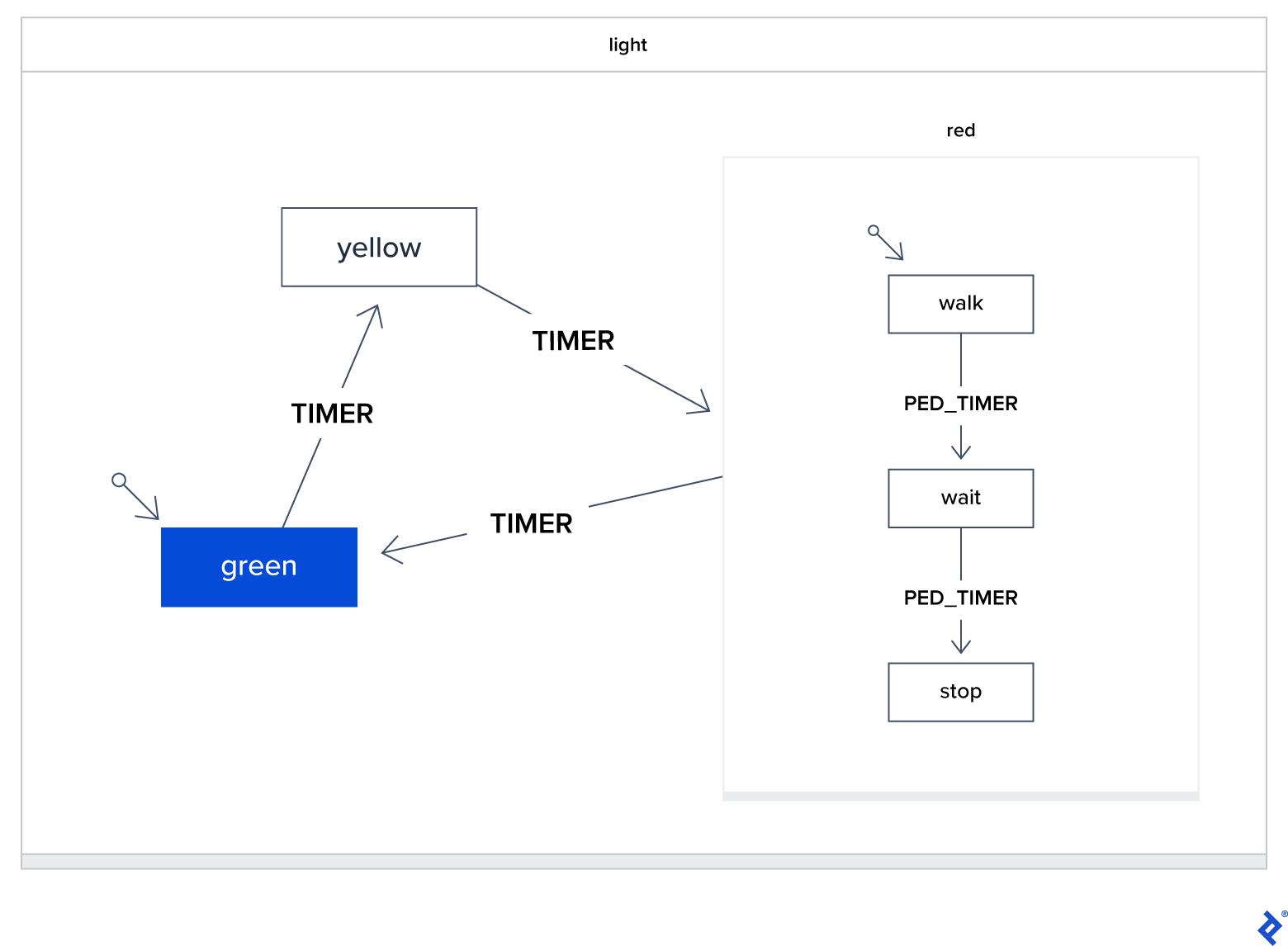

The benefits stem from how FSMs manage state. An FSM can exist in only one state at a time and has a limited set of transitions to neighboring states in response to external events (like mouse clicks or server responses). This often leads to a significant reduction in defects. However, traditional FSMs can be difficult to scale for large applications.

Statecharts, a more recent extension to FSMs, address this limitation by providing visualization and scalability for complex FSMs, making them suitable for much larger applications. This article concentrates on this statechart flavor of finite-state machines. We’ll be using the XState library, a top-tier solution for FSMs and statecharts in JavaScript, for our demonstrations.

Declarative Back-End Development with Node.js

Building a web server back end using declarative approaches is a broad topic that often starts with choosing an appropriate functional programming language. For this article, let’s assume you’ve already decided on (or are considering) Node.js for your back end.

This section presents a way to model entities on the back end with the following advantages:

- Enhanced code clarity

- Safer code refactoring

- Potential performance improvements due to type safety

Ensuring Behavior with Type Modeling

JavaScript

Imagine retrieving a user by their email address from a database using JavaScript:

| |

This function takes an email string as input and returns the corresponding user from the database if a match is found.

This assumes that lookupUser() is called only after basic validation. This is a crucial assumption. What happens if weeks later, refactoring occurs, and this assumption is no longer valid? We can only hope that unit tests would catch this issue; otherwise, we might end up sending unfiltered input to the database!

TypeScript (Initial Approach)

Now, let’s look at a TypeScript equivalent of this validation function:

| |

This is a slight improvement, as the TypeScript compiler now prevents us from needing an extra runtime validation step.

However, we haven’t yet fully utilized the safety that strong typing can offer. Let’s explore this further.

TypeScript (Improved Approach)

Let’s enhance type safety and prevent unprocessed strings from being passed as input to looukupUser:

| |

While better, this approach is cumbersome. Every use of ValidEmail needs to access the actual address via email.value. This is because TypeScript utilizes structural typing, unlike languages like Java and C# that use nominal typing.

While powerful, structural typing means that any other type conforming to this structure is considered equivalent. For instance, the following password type could be passed to lookupUser() without the compiler raising an error:

| |

TypeScript (Final Approach)

We can achieve nominal typing in TypeScript using intersection types:

| |

Now we’ve accomplished our goal: only validated email strings can be passed to lookupUser().

Pro Tip: Simplify the application of this pattern with the following helper type:

| |

Advantages

By using strong typing for entities in your domain, you can:

- Minimize the need for runtime checks, which consume valuable server CPU cycles (even though the impact of each check is small, they accumulate when handling thousands of requests per minute).

- Reduce reliance on basic tests due to the guarantees provided by the TypeScript compiler.

- Utilize editor- and compiler-assisted refactoring tools effectively.

- Improve code readability by enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio.

Considerations

Type modeling does come with tradeoffs:

- Introducing TypeScript typically adds complexity to the toolchain, potentially increasing build times and test execution times.

- If your priority is rapid prototyping and user feedback, the overhead of explicit type modeling and propagation might not be justified.

We’ve illustrated how existing server-side JavaScript code or shared back-end/front-end validation logic can be augmented with types. This results in more readable code and enables safer refactoring, both crucial for team development.

Declarative User Interfaces

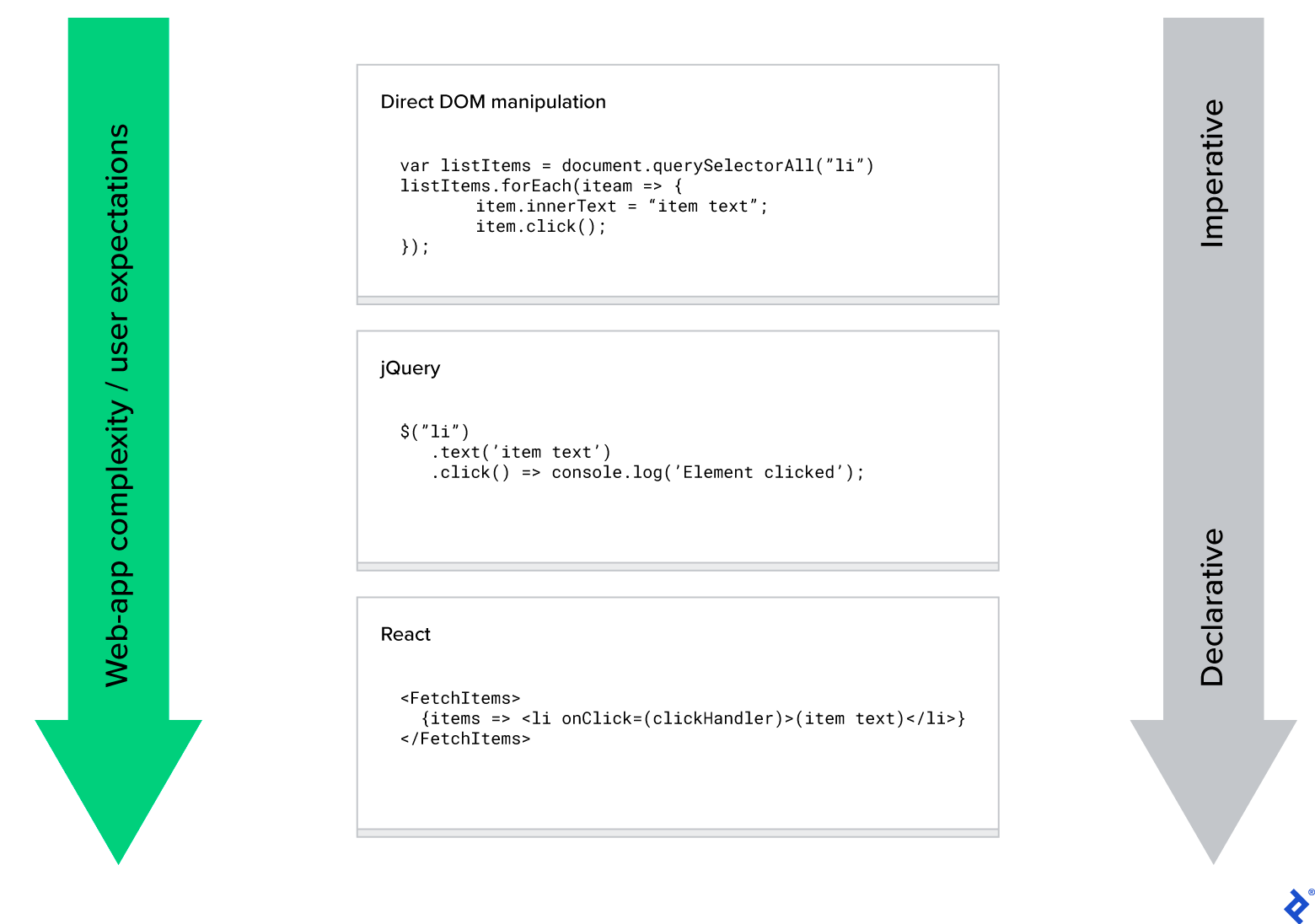

User interfaces built with declarative programming prioritize describing “what” the UI should look like over “how” it’s implemented. Two of the web’s fundamental building blocks, CSS and HTML, exemplify declarative languages that have proven their effectiveness for over 1 billion websites.

React, open-sourced by Facebook in 2013, significantly changed the landscape of front-end development. What I loved when I first used React was how it enabled me to declare the GUI as a function of the application’s state. I could then compose complex UIs from smaller, reusable components without getting bogged down in the complexities of direct DOM manipulation or keeping track of UI updates in response to user actions. The temporal aspect of UI development became less of a concern, allowing me to focus on ensuring smooth transitions between application states.

To simplify UI development, React introduced an abstraction layer between the developer and the browser/machine: the virtual DOM.

Other modern UI frameworks have taken different approaches to address this. Vue, for example, uses functional reactivity through either JavaScript getters/setters (Vue 2) or proxies (Vue 3). Svelte achieves reactivity by incorporating an additional source code compilation step.

The common thread here is a clear desire within the industry to equip developers with more effective and intuitive tools to express application behavior using declarative methods.

Declarative Application State and Logic

While the presentation layer continues to be based on HTML or HTML-like structures (like JSX in React, or templates in Vue, Angular, and Svelte), the challenge of modeling an application’s state in a comprehensible and maintainable way remains. The proliferation of state management libraries and approaches is evidence of this ongoing challenge.

This situation is further complicated by the growing demands of modern web apps. Emerging challenges for state management approaches include:

- Support for offline-first applications with sophisticated caching and subscription mechanisms

- Maintaining concise code and optimizing for minimal bundle sizes

- Meeting the demand for increasingly sophisticated user experiences with high-fidelity animations and real-time updates

The Comeback of Finite-state Machines and Statecharts

Finite-state machines have a strong track record in software development within industries where application robustness is critical, such as aviation and finance. They are also gaining popularity in front-end web development, thanks in part to excellent libraries like XState library.

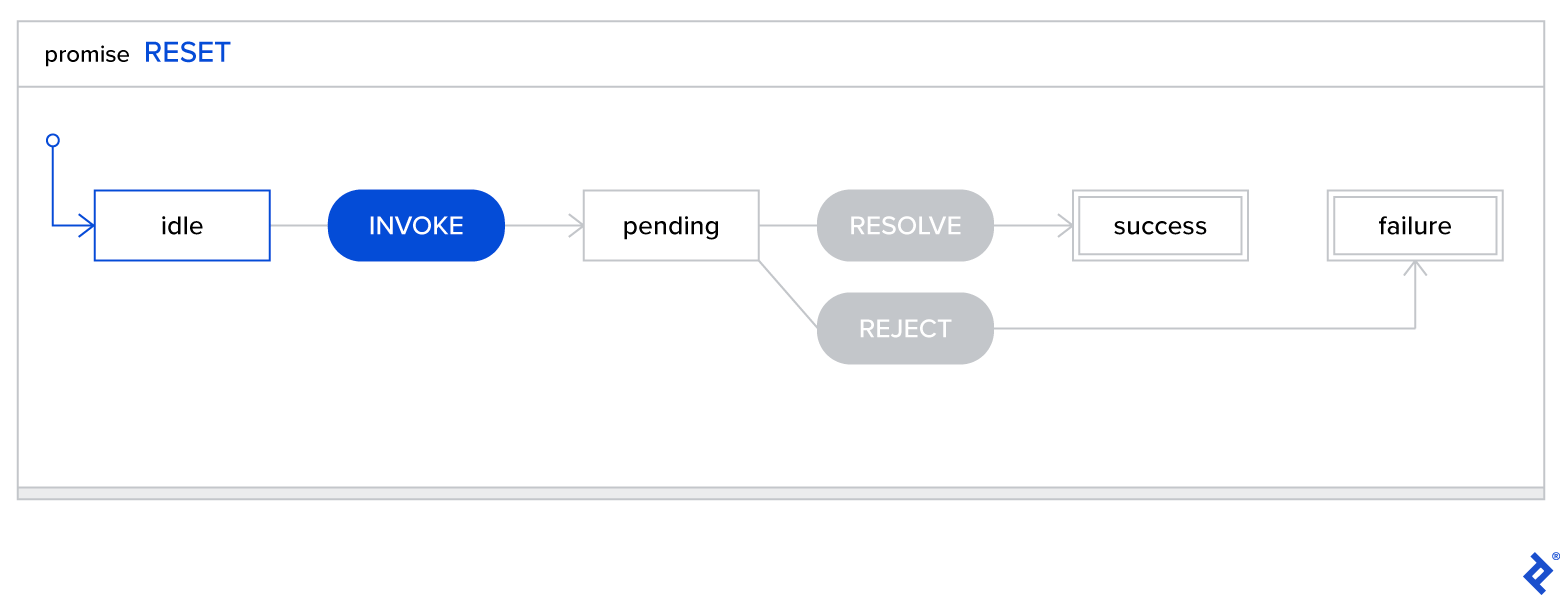

Wikipedia defines a finite-state machine as:

An abstract machine that can be in exactly one of a finite number of states at any given time. The FSM can change from one state to another in response to some external inputs; the change from one state to another is called a transition. An FSM is defined by a list of its states, its initial state, and the conditions for each transition.

It further explains:

A state is a description of the status of a system that is waiting to execute a transition.

Basic FSMs are not ideal for large systems because of the state explosion problem. UML statecharts were introduced to address this by extending FSMs with hierarchy and concurrency, features that have made FSMs more suitable for large-scale applications.

Expressing Application Logic Declaratively

Let’s see what an FSM looks like in code. There are various ways to implement a finite-state machine in JavaScript.

- Finite-state machine as a switch statement

Here is a machine illustrating the potential states of JavaScript code, using a switch statement:

| |

This style of code might be familiar to developers who have worked with the popular Redux state management library.

- Finite-state machine as a JavaScript object

Here is the same machine represented as a JavaScript object using the XState library:

| |

The XState version might appear less concise, but the object representation offers several advantages:

- The state machine itself is simple JSON, which can be stored persistently.

- Because the representation is declarative, the machine can be visualized.

- When using TypeScript, the compiler ensures that only valid state transitions occur.

XState’s support for statecharts and adherence to the SCXML specification make it suitable for use in very large applications.

Statecharts visualization of a promise:

Best Practices with XState

When working with XState, following these best practices can help maintain project maintainability.

Decoupling Side Effects from Logic

XState allows the separation of side effects (like API calls or logging) from the core logic of the state machine.

This separation offers several benefits:

- Easier identification of logic errors by keeping the state machine code clean and focused.

- Straightforward visualization of the state machine without the need to remove boilerplate code.

- Simplified testing of the state machine through mock service injection.

| |

While it might be tempting to write state machines like this during initial development, a cleaner separation of concerns can be achieved by passing side effects as options:

| |

This separation also simplifies unit testing of the state machine, allowing explicit mocking of actions like user fetches:

| |

Managing Large Machines

Determining the optimal way to structure a problem domain into a well-organized finite-state machine hierarchy might not be immediately clear when starting a project.

Tip: Use the existing hierarchy of your UI components as a guide for this process. The next section explains how to map state machines to UI components.

A major advantage of state machines is the explicit modeling of all possible states and transitions, making the resulting behavior easy to understand and potential logic errors or gaps easier to identify.

To ensure effectiveness, machines need to remain small and focused. Fortunately, state machines can be easily composed hierarchically. Consider the classic traffic light system example. In this case, the “red” state itself becomes a child state machine. The parent “light” machine doesn’t concern itself with the internal states of “red,” focusing instead on when to transition into “red” and the intended behavior when exiting:

One-to-One Mapping: State Machines to UI Components

Let’s imagine a simplified fictional eCommerce site with these React views:

| |

The process of creating corresponding state machines for these views might resonate with those familiar with Redux:

- Determine if the component requires state management. The Admin/Products view, for example, might not; simple pagination for server requests with client-side caching (like SWR) might suffice. In contrast, components like SignInForm or the Cart usually require state management to handle things like form data or cart contents.

- Assess if local state management techniques are sufficient. For instance, tracking the visibility of a cart popup modal likely doesn’t necessitate a finite-state machine. React’s

setState() / useState()would be sufficient. - Evaluate the potential complexity of the resulting state machine. If a machine becomes too complex, break it down into smaller, more manageable machines. Look for opportunities to create reusable child machines. For example, the SignInForm and RegistrationForm machines could both utilize a shared child

textFieldMachineto manage validation and state for common fields like user email, name, and password.

When are Finite-state Machines the Right Choice?

While statecharts and FSMs offer elegant solutions to certain challenges, the optimal tools and approaches for any application depend on several factors.

Scenarios where finite-state machines are particularly well-suited:

- Applications with complex data entry forms where field visibility or accessibility is governed by intricate rules, such as insurance claim forms. FSMs help ensure robust implementation of these rules. The visualization capabilities of statecharts can also be leveraged to enhance collaboration with non-technical stakeholders and clarify detailed business requirements early in the development process.

- Applications that require handling of complex asynchronous data flows to deliver a smoother user experience, especially on slower connections. FSMs explicitly define all possible states, and statecharts’ visual nature aids in diagnosing and resolving asynchronous data-related issues.

- Applications with sophisticated, state-driven animations. RxJS is a popular choice for modeling complex animations as event streams. While this works well in many cases, FSMs provide well-defined “resting points” for animations to transition between, which is particularly valuable when rich animation is coupled with a complex series of known states. The combination of FSMs and RxJS seems ideal for creating the next generation of expressive and responsive user experiences.

- Feature-rich client-side applications like image or video editors, diagramming tools, or games where a significant portion of the business logic resides on the client-side. FSMs are inherently decoupled from specific UI frameworks, and their testability allows for rapid iteration and confident shipping of high-quality applications.

Considerations When Using Finite-state Machines

- Learning curve: The general concepts, best practices, and APIs of statechart libraries like XState might be unfamiliar to most front-end developers, requiring an investment of time and resources for teams to become productive, especially for less experienced teams.

- Community and resources: Although XState is gaining popularity and has good documentation, established libraries like Redux, MobX, or React Context have larger communities and more extensive online resources, which XState doesn’t yet match.

- Overkill for simpler applications: For applications following a simpler CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) model, existing state management solutions combined with a robust caching library (such as SWR or React Query) might be sufficient. In these cases, the additional constraints of FSMs, while beneficial in complex applications, might hinder development speed.

- Tooling maturity: The tooling for statecharts is still maturing compared to other state management libraries. Improvements in TypeScript support and browser developer tools are ongoing.

Conclusion

Declarative programming continues to gain traction and adoption within the web development community.

As web development grows in complexity, libraries and frameworks embracing declarative principles are emerging more frequently. The rationale is clear: there’s a need for simpler and more descriptive ways to build software.

Strongly-typed languages like TypeScript enable concise and explicit modeling of application domain entities, reducing the potential for errors and minimizing the need for error-prone checking code. On the front end, adopting finite-state machines and statecharts allows developers to represent business logic declaratively through state transitions. This, in turn, enables the creation of valuable visualization tools and fosters closer collaboration with non-developers.

By making these shifts, we move away from the intricacies of how an application works internally and towards a higher-level perspective. This empowers us to prioritize customer needs and create lasting value.