I began with the intention of crafting a detailed walkthrough for migrating an application from Angular 1.5 to Angular 2. However, my editor wisely advised that a concise article, rather than an extensive manual, would be more suitable. After careful consideration, I agreed to start by presenting a comprehensive overview of the advancements introduced in Angular 2, drawing upon the key points outlined in Jason Aden’s Getting Past Hello World in Angular 2 article. …Oops. While that resource provides a great general understanding of Angular 2’s new aspects, for a practical, hands-on exploration, please remain on this page.

My goal is to develop this into a series that will ultimately encompass the complete transition of our demo application to Angular 2. But for the time being, we’ll focus on a single service. Let’s embark on a detailed examination of the code, during which I’ll address any questions you might have, such as….

Angular: The Conventional Approach

If your experience mirrors mine, the Angular 2 quickstart guide might have marked your initial encounter with TypeScript. In a nutshell, as per its own website, TypeScript is “a typed superset of JavaScript that compiles to plain JavaScript”. Upon installing the transpiler (akin to Babel or Traceur), you gain access to a powerful language that supports ES2015 & ES2016 language features alongside strong typing.

Rest assured that this seemingly intricate setup is not mandatory. It’s not overly difficult to write Angular 2 code in plain old JavaScript, though I wouldn’t recommend it. While it’s comforting to recognize familiar elements, the truly captivating aspects of Angular 2 lie in its paradigm shift rather than its architectural changes.

Now, let’s analyze the service that I migrated from Angular 1.5 to 2.0.0-beta.17. It’s a fairly typical Angular 1.x service, with a few notable characteristics that I’ve highlighted in the comments. Although slightly more involved than your average rudimentary application, its primary function is querying Zilyo, a freely-available API that gathers listings from rental platforms such as Airbnb. Please bear with the extensive code snippet.

zilyo.service.js (1.5.5)

| |

The unique challenge in this application stems from displaying results on a map. Other services handle multiple result pages using pagination or lazy loading, retrieving one page at a time. However, we aim to showcase all results within the search area instantaneously as they arrive from the server, rather than abruptly revealing them after all pages load. Moreover, we want to provide users with progress updates to keep them informed.

To achieve this in Angular 1.5, we rely on callbacks. Promises partially address this, as evident in the $q.all wrapper triggering the onCompleted callback. However, things still become somewhat convoluted.

Introducing lodash helps generate all the page requests, each responsible for executing the onFetchPage callback to ensure immediate map addition upon availability. However, this introduces its own complexities. As the comments reveal, I became entangled in my own logic, struggling to track the data flow between promises.

The code’s overall elegance suffers further (exceeding necessity) because confusion only exacerbates the issue. Let’s collectively acknowledge the truth…

Angular 2: A Fresh Perspective

Fortunately, there’s a superior approach, which I’ll gladly demonstrate. I won’t delve deeply into ES6 (also known as ES2015) concepts as numerous excellent resources cover them extensively. If you seek a starting point, ES6-Features.org offers a solid overview of the exciting new features. Consider the following updated AngularJS 2 code:

zilyo.service.ts (2.0.0-beta.17)

| |

Impressive! Let’s break it down step by step. The TypeScript transpiler grants us the freedom to utilize ES6 features since it translates everything into standard JavaScript.

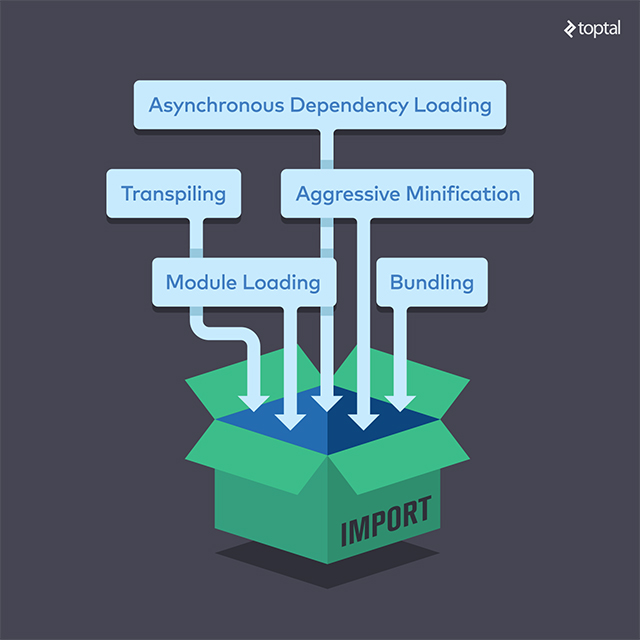

The initial import statements leverage ES6 for loading the necessary modules. Accustomed to ES5 (regular JavaScript) development, I find it slightly inconvenient to explicitly declare every object I intend to use.

However, remember that TypeScript ultimately transpiles everything into JavaScript, discreetly employing SystemJS for module loading. Dependencies load asynchronously, and it purportedly bundles code intelligently, omitting unused symbols. Furthermore, it boasts support for “aggressive minification,” a rather daunting concept. Those import statements are a small price to pay for a cleaner, more manageable codebase.

Besides selectively importing features from Angular 2, pay close attention to import {Observable} from 'rxjs/Observable';. RxJS is an impressive, mind-boggling reactive programming library that forms part of Angular 2’s foundation. We’ll definitely revisit it later.

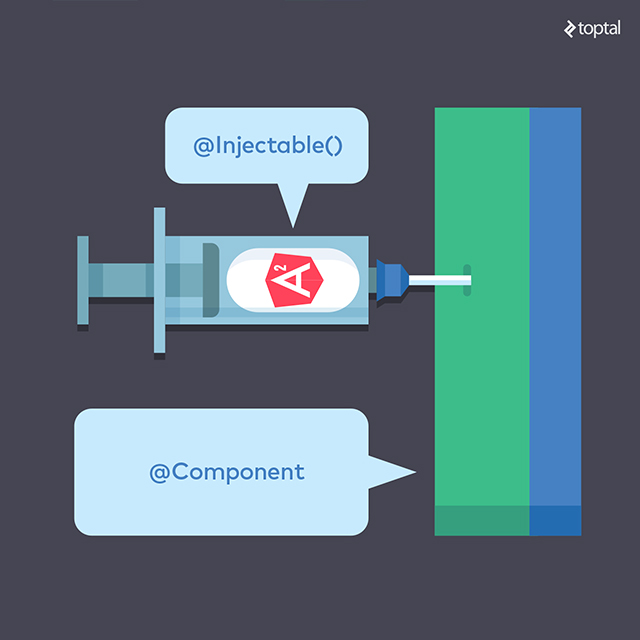

Next comes @Injectable().

To be frank, its exact function remains somewhat unclear to me. However, the beauty of declarative programming lies in not needing to grasp every intricate detail. It’s called a decorator, an elegant TypeScript construct that applies properties to the subsequent class (or other object). In this instance, @Injectable() equips our service with the knowledge of how to be injected into a component. While the official documentation provides the most accurate explanation, it tends to be lengthy. So here’s a glimpse of its implementation in our AppComponent:

| |

Moving on to the class definition itself, we see an export statement, implying, as you might have guessed, that we can import our service into another file. Practically speaking, we’ll import it into our AppComponent component, as shown earlier.

Following the class definition is the constructor, where we witness dependency injection in action. The line constructor(private http:Http) {} introduces a private instance variable named http, which TypeScript cleverly recognizes as an instance of the Http service. Kudos to TypeScript!

Beyond this, we have some standard instance variables and a utility function before reaching the heart of the matter, the get function. This is where we see Http in action. Although it resembles Angular 1’s promise-based approach, its underlying mechanism is far more sophisticated. Built on RxJS, it offers two significant advantages over promises:

- The ability to cancel the

Observableif the response is no longer relevant. This is useful in scenarios like typeahead autocomplete fields, where results for “ca” become irrelevant once the user types “cat.” - The ability of the

Observableto emit multiple values, invoking the subscriber repeatedly to consume them as they are produced.

While the first advantage is valuable in various situations, our focus lies on the second one within our new service. Let’s dissect the get function line by line:

| |

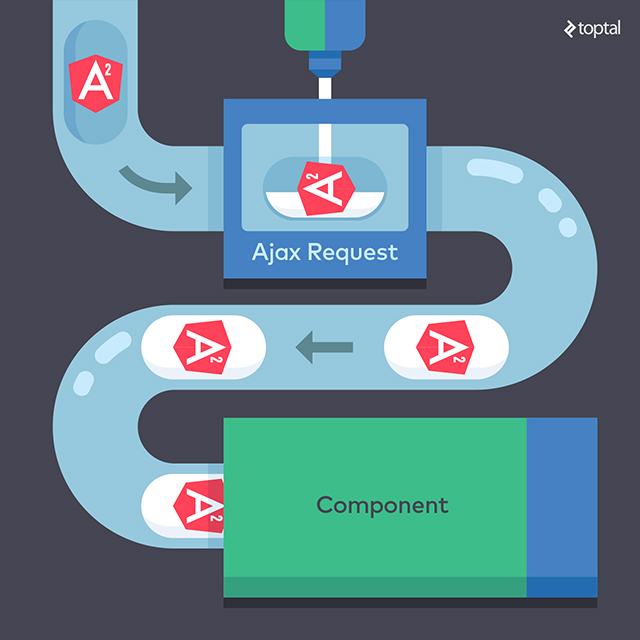

This appears similar to the promise-based HTTP call in Angular 1. Here, we send the query parameters to retrieve a count of all matching results.

| |

Upon completion of the AJAX call, the response is sent downstream. The map method, conceptually similar to an array’s map function, also behaves like a promise’s then method by waiting for the upstream operation to finish, regardless of its synchronous or asynchronous nature. In this case, it simply extracts the JSON data from the response object and passes it downstream. Now we have:

| |

We still have one lingering callback, onCountResults, which we need to incorporate. It’s not pure magic, but we can process it immediately upon the AJAX call’s return, all without disrupting our stream. Not too shabby. Moving onto the next line:

.flatMap(results => Observable.range(1, results.totalPages))

Can you sense it? A palpable tension has gripped the audience as they anticipate something significant. What does this line even signify? The right-hand side isn’t particularly complex. It generates an RxJS range, essentially an Observable-wrapped array. If results.totalPages equals 5, the result resembles Observable.of([1,2,3,4,5]).

flatMap is, as the name suggests, a fusion of flatten and map. A helpful video illustrating this concept is available at Egghead.io. However, my approach involves visualizing each Observable as an array. Observable.range creates its own wrapper, resulting in a 2-dimensional array [[1,2,3,4,5]]. flatMap flattens this outer array into [1,2,3,4,5], followed by map iterating over the array and passing the values downstream one by one. In essence, this line takes an integer (totalPages) and transforms it into a stream of integers from 1 to totalPages. While seemingly insignificant, this sets the stage for the next step.

Ideally, this would be on a single line for greater impact, but some battles are lost. This line showcases the fate of the integer stream generated in the previous step. The integers flow in sequentially, get incorporated into the query as page parameters, and are then packaged into new AJAX requests dispatched to fetch individual result pages. Here’s the code:

| |

If totalPages was 5, we construct and send 5 concurrent GET requests. flatMap subscribes to each new Observable. Consequently, as the requests return (in any order), they are unwrapped, and each response (representing a page of results) is pushed downstream individually.

Let’s shift perspectives and analyze the process as a whole. Starting with the initial “count” request, we determine the total pages of results. For each page, we create a new AJAX request. Regardless of their return order or timing, these requests are pushed into the stream as soon as they are ready. Our component merely needs to subscribe to the Observable returned by our get method to receive each page sequentially from a single stream. Take that, promises.

The remaining code feels somewhat anticlimactic after this:

| |

As each response object arrives from flatMap, we extract its JSON, mirroring the process for the count request response. Appended to the end is the catch operator, illustrating the mechanics of stream-based RxJS error handling. It’s reminiscent of the traditional try/catch paradigm but adapted for asynchronous error handling within the Observable object.

Upon encountering an error, it races downstream, bypassing operators until reaching an error handler. In this case, the handleError method re-throws the error, enabling interception within the service while allowing the subscriber to provide its own onError callback, extending the error handling downstream. This highlights that we haven’t fully exploited our stream’s potential despite our achievements. Adding a retry operator after our HTTP requests, retrying failed individual requests, is trivial. As a precaution, we could insert an operator between the range generator and the requests to implement rate-limiting, preventing server overload from excessive requests.

Recap: Learning Angular 2 Is More Than Just a New Framework

Learning Angular 2 is akin to encountering an entirely new family with complex relationships. Hopefully, I’ve demonstrated that these relationships serve a purpose and respecting the dynamics within this ecosystem yields substantial benefits. I trust you found this article insightful as I’ve barely scratched the surface of this vast topic, leaving much more to explore.