Similar to other content management systems (CMS), WordPress may not fulfill all your requirements directly. Thanks to its open-source nature, you have the option to modify its code to align with your business needs. However, a more preferable approach is to utilize WordPress’ hooks. Employing hooks is a beneficial method that empowers [WordPress developers to create practically any website feature they can envision.

WordPress Hooks: Actions and Filters

[WordPress hooks] are more than just robust customization tools; they represent the mechanism by which different WordPress components interact. Functions connected to hooks govern numerous routine operations inherent to WordPress, such as integrating stylesheets or scripts into a page or encapsulating footer text with HTML elements. A comprehensive examination of WordPress Core’s code reveals thousands of hooks in over 700 instances, with WordPress themes and plugins incorporating even more.

Before delving into hooks and examining the distinction between action hooks and filter hooks, let’s establish their position within the overall framework of WordPress.

WordPress Infrastructure

WordPress’ modular components seamlessly integrate with each other, facilitating effortless mixing, matching, and combination of:

- WordPress Core: These constitute the files required for WordPress to work. WordPress Core furnishes the fundamental architecture, encompassing the WP Admin dashboard, database interactions, security measures, and more. It is written in PHP and relies on a MySQL database.

- Theme (or Parent Theme): A theme establishes the foundational layout and visual presentation of a website. Utilizing PHP, HTML, JavaScript, and CSS files, a theme operates by retrieving data from the WordPress MySQL database to produce the HTML code rendered in a browser. Hooks within a theme can incorporate elements such as stylesheets, scripts, fonts, or custom post types.

- Child Theme: We can generate child themes to fine-tune the fundamental layout and design inherited from parent themes. These child themes have the capability to define stylesheets and scripts to modify inherited elements or to add or remove post types. Instructions specified in a child theme invariably take precedence over those in the parent theme.

- Plugin(s): A wide array of thousands of third-party plugins is available to augment the back-end functionalities of WordPress. Hooks within a plugin can, for instance, send email notifications upon post publication or conceal user comments that contain prohibited language.

- Custom Plugin(s): In situations where a third-party plugin doesn’t fully address business requirements, we can enhance it by developing a custom plugin using PHP. Alternatively, we can create an entirely new plugin from scratch. In both scenarios, we would integrate hook(s) to expand upon existing functionalities.

Considering our access to the source code of all five layers, why is there a need for hooks in WordPress?

Code Safety

In order to remain current with evolving technologies, contributors to WordPress Core, parent themes, and plugins regularly release updates to address security vulnerabilities, rectify bugs, resolve compatibility issues, and introduce new features. As any seasoned consultant can attest, neglecting to update WordPress components can jeopardize or even render a site inoperable.

Directly altering local copies of upstream WordPress components presents a challenge: updates overwrite our customizations. How can we circumvent this when customizing WordPress? The answer lies in utilizing hooks within the child theme and custom plugin(s).

Coding in Our Child Theme

A child theme serves as a secure environment for customizing the appearance and behavior of our installed theme. Any code introduced here will override corresponding code in the parent theme without the risk of being overwritten during an update.

When a child theme is activated, it establishes a link to a deactivated parent, inheriting and displaying the parent’s characteristics while remaining unaffected by updates to the parent. To resist the temptation to modify the parent theme directly, it is considered best practice to activate a child theme as part of our setup.

Writing Custom Plugin(s)

Upon activation of a plugin, its functions.php file is executed with every server request. WordPress, in turn, loads and orders hooks from all active plugins based on their priority, executing them sequentially. To extend the capabilities of a third-party plugin, we have the option of creating our own custom WordPress plugin.

Where to Place Our Hooks in WordPress

| Goal | Example | Where? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child Theme PHP | Custom Plugin PHP | ||

| To modify the structure of a web page | Adding a custom stylesheet to change the colors and fonts of website elements | ✔ | |

| To modify the functionality of another plugin (i.e., create a plugin to enhance the functionality of a third-party plugin) | Adding a subheading (e.g., “News”) to custom post types | ✔ | |

| To add a new feature that goes beyond WordPress Core | Modifying the workflow that takes place when a post is visited to include updating a counter in the database | ✔ |

Pre-dive Prep: Definitions

To avoid any confusion, let’s adhere to the following terminology:

- A hook represents a designated point within WordPress where functions are registered for execution. We have the flexibility to connect our functions to existing hooks in WordPress and its components or establish our own.

- An action hook triggers the execution of actions.

- A filter hook triggers the execution of filters.

- A hooked function is a custom PHP callback function that we have “hooked” into a specific WordPress hook location. The appropriate type to employ depends on whether the hook is designed to permit modifications outside the function’s scope—for instance, directly appending content to the webpage output, altering the database, or sending an email. These are referred to as side effects.

- A filter (or filter function) should refrain from side effects, focusing solely on processing and returning a modified copy of the data passed to it.

- In contrast, an action (or action function) is intended to produce side effects and does not return a value.

With these distinctions in mind, we can now embark on our exploration of hooks.

Abstraction and Clean Code

By incorporating an action or filter into a hook as needed, we adhere to the principles of writing a single function per task and avoiding code repetition within a project. For instance, let’s assume we want to include the same stylesheet in three different page templates (archive, single page, and custom post) within our theme. Instead of overriding each template in the parent theme, replicating them in our child theme, and then manually adding stylesheets to individual head sections, we can consolidate the code into a single function and attach it to the wp_head hook.

Thoughtful Nomenclature

To prevent conflicts proactively, it’s essential to assign unique names to child theme or custom plugin hooks. Using identical hook names within a single site can lead to unpredictable code behavior. Best practices recommend prefixing hook names with a distinctive, concise identifier (e.g., author’s, project’s, or company’s initials) followed by a descriptive hook name. For example, adopting the pattern “project initials plus hook name” for a project named “Tahir’s Fabulous Plugin,” we could name our hooks tfp-upload-document or tfp-create-post-news.

Concurrent Development and Debugging

A single hook can trigger multiple actions or filters. For instance, a web page might contain several scripts, each utilizing the wp_head action hook to insert HTML (e.g., a <style> or <script> section) within the <head> section of the rendered page.

This approach enables multiple plugin developers to work on different aspects of a single plugin concurrently or to decompose the plugin into smaller, more manageable individual plugins. In the event of a feature malfunction, we can directly investigate and debug its associated hooked function without having to search the entire project.

Actions

An action executes code in response to a specific event occurring within WordPress. Actions can carry out operations such as:

- Data creation

- Data retrieval

- Data modification

- Data deletion

- Recording logged-in user permissions

- Tracking and storing locations in the database

Examples of events that can trigger actions include:

init, which occurs after WordPress has loaded but before sending headers to the output streamsave_post, triggered when a post is savedwp_create_nav_menu, executed immediately after a navigation menu is successfully created

While an action can interact with an API to transmit data (e.g., sharing a post link on social media), it does not return data to the calling hook.

Let’s say we want to automate the process of sharing all new posts from our site on social media. We’ll start by searching the WordPress documentation for a suitable hook that triggers whenever a post is published.

Finding the right hook requires either prior experience or a thorough examination of the listed actions to identify potential candidates. While save_post might seem like an option, it’s quickly dismissed because it would trigger multiple times during a single editing session. A more appropriate choice is transition_post_status, which activates only when a post’s status changes (e.g., from draft to publish, from publish to trash).

We’ll proceed with transition_post_status but refine our action to run solely when the post status transitions to publish. Furthermore, by adhering to the official documentation and APIs of the respective social media platforms, we can integrate and publish our post’s content along with a featured image:

| |

Now that we understand how to work with action hooks, let’s explore one that’s particularly useful, especially in the context of CSS.

Designating Priorities With wp_enqueue_scripts

Suppose we want to ensure that our child theme’s stylesheet loads last, after all other stylesheets, to guarantee that any identically named classes from other sources are overridden by our child theme’s classes.

By default, WordPress loads stylesheets in the following order:

- Parent theme’s stylesheet

- Child theme’s stylesheet

- Stylesheets from any plugins

In this structure:

| |

… the priority value assigned to the added action determines its execution order:

- The default

priorityvalue forwp_enqueue_scripts(and any action) is “10.” - Assigning a lower

prioritynumber to a function will cause it to run earlier. - Assigning a higher

prioritynumber to a function will cause it to run later.

To ensure our child theme’s stylesheet loads last, we’ll utilize wp_enqueue_scripts, an action frequently employed by WordPress themes and plugins. We simply need to modify the priority of our child theme’s wp_enqueue_scripts action to a value greater than the default “10,” such as “99”:

| |

Generally, we employ actions when we don’t require return values. To return data to the calling hook, we need to shift our focus to filters.

Filters

Filters provide a mechanism to modify data before it undergoes processing for display in a browser. A filter accepts one or more variables, modifies their values, and returns the data for further processing.

WordPress checks for and executes all registered filters prior to preparing content for browser display. This allows us to manipulate data before it’s sent to the browser or database, as needed.

To illustrate, consider a client who personalizes products by imprinting customer-provided images. This client uses the WooCommerce plugin to manage their e-commerce operations. However, WooCommerce doesn’t offer this functionality out of the box. To address this, I added two code snippets to the client’s functions.php file:

woocommerce_checkout_cart_item_quantity, documented in the WooCommerce documentation, is a filter hook that allows customers to incorporate external elements into their carts before checkout.my_customer_image_data_in_cartis a custom filter we’ll create to triggerwoocommerce_checkout_cart_item_quantitywhenever WooCommerce prepares a cart for display.

Using the following template, we can implement our filter and customize the cart’s default behavior:

| |

We add filters in a manner similar to adding actions. Filters operate analogously to actions, including how priorities are handled. The key distinction lies in their data handling: an action does not return data to the calling hook, while a filter does.

Customized Action Hooks and Filter Hooks

Creating custom action hooks doesn’t directly extend WordPress Core; rather, it establishes new trigger points within our own code.

Creating Custom Action Hooks

Introducing a custom hook in our theme or plugin empowers other developers to extend functionality without altering our codebase. To create a custom hook, we follow the same approach used within the WordPress Core codebase: at the desired trigger point, we simply invoke do_action with the name of our new hook, optionally passing any arguments that our callbacks might utilize:

| |

This code snippet executes any callback functions hooked onto our custom hook. Notably, the namespace is global, so as previously advised, it’s recommended to prefix custom hook names with a shortened version of our organization’s name (and potentially our project’s name), hence the use of myorg_ here.

With myorg_hello_action defined, it becomes accessible for developers to hook into, using the same method described earlier for built-in hooks: define a function, then call add_action().

Unless the intention is to use a new hook solely internally—which can be beneficial for code organization—it’s crucial to clearly document its availability to downstream developers, whether team members or external users of our plugin.

Creating Custom Filter Hooks

The pattern for creating custom filter hooks in WordPress mirrors that of action hooks, with the exception that we invoke apply_filters() instead of do_action().

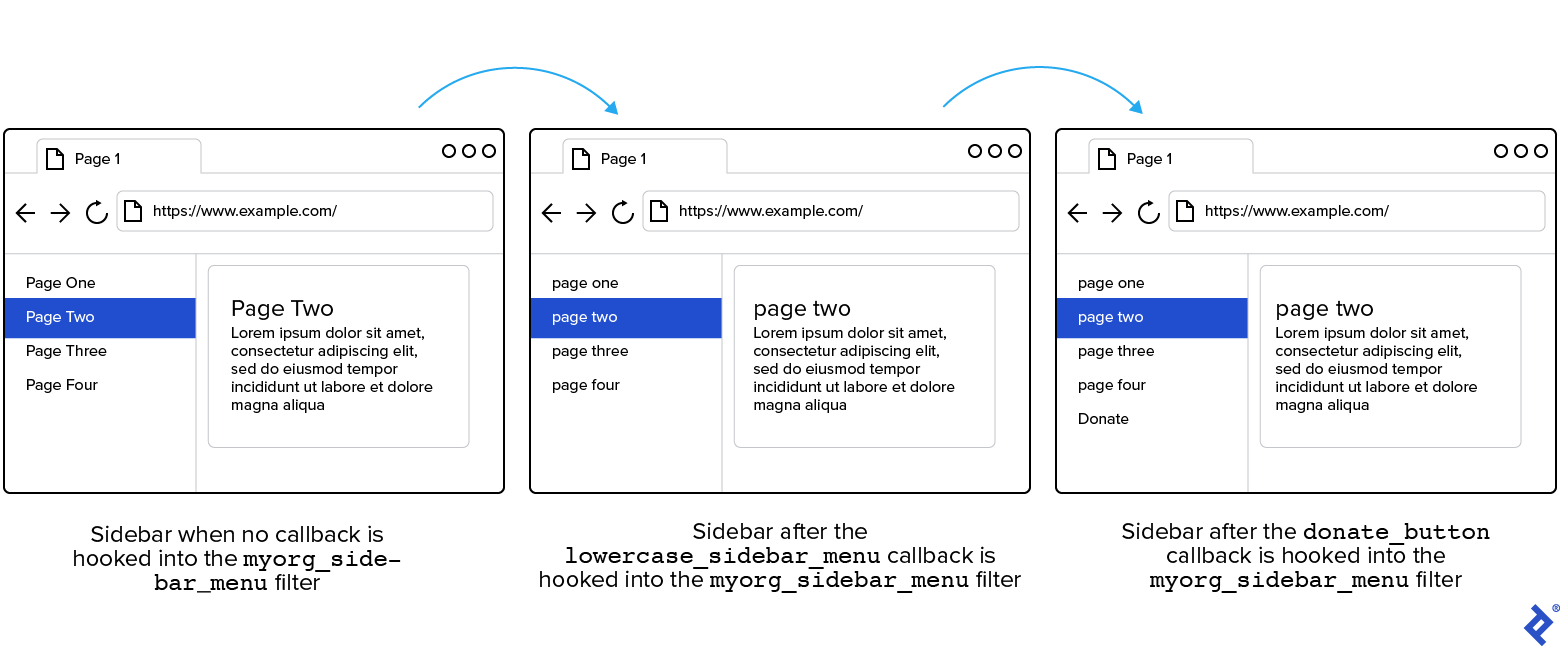

Let’s walk through a more concrete example. Imagine our plugin generates a sidebar menu typically containing four items. We’ll introduce a custom filter hook to enable us (and downstream developers) to modify this item list from elsewhere:

| |

And there we have it—our custom filter hook, myorg_sidebar_menu, is now ready for use in plugins loaded subsequently or even within the same plugin. This empowers anyone writing downstream code to customize our sidebar.

When utilizing this hook, we or other developers will follow the same pattern as with a built-in WordPress hook. That is, we’ll begin by defining callback functions that return a modified version of the data they receive:

| |

Similar to our previous examples, we’re now prepared to hook our filter callback functions to our custom hook:

| |

With that, we’ve successfully hooked our two example callback functions onto our custom filter hook. Both functions now modify the original content of $the_sidebar_menu. Due to the higher priority value assigned to add_donate_item, it executes after lowercase_sidebar_menu.

Downstream developers retain the freedom to hook additional callback functions to myorg_sidebar_menu. As they do so, they can leverage the priority parameter to control the execution order of their hooks relative to our two example callback functions.

The Sky’s the Limit With Actions and Filters

By harnessing the power of actions, filters, and hooks, we can expand WordPress functionality exponentially. This enables us to develop custom features for our site while ensuring our contributions remain as extensible as WordPress itself. Hooks empower us to adhere to safety and best practices as we elevate our WordPress site to new heights.

The Toptal Engineering Blog expresses its sincere gratitude to Fahad Murtaza for his invaluable expertise, beta testing, and technical review of this article.