This piece is intended for software developers and project managers interested in understanding software entropy, its impact on their projects, and the factors contributing to its rise.

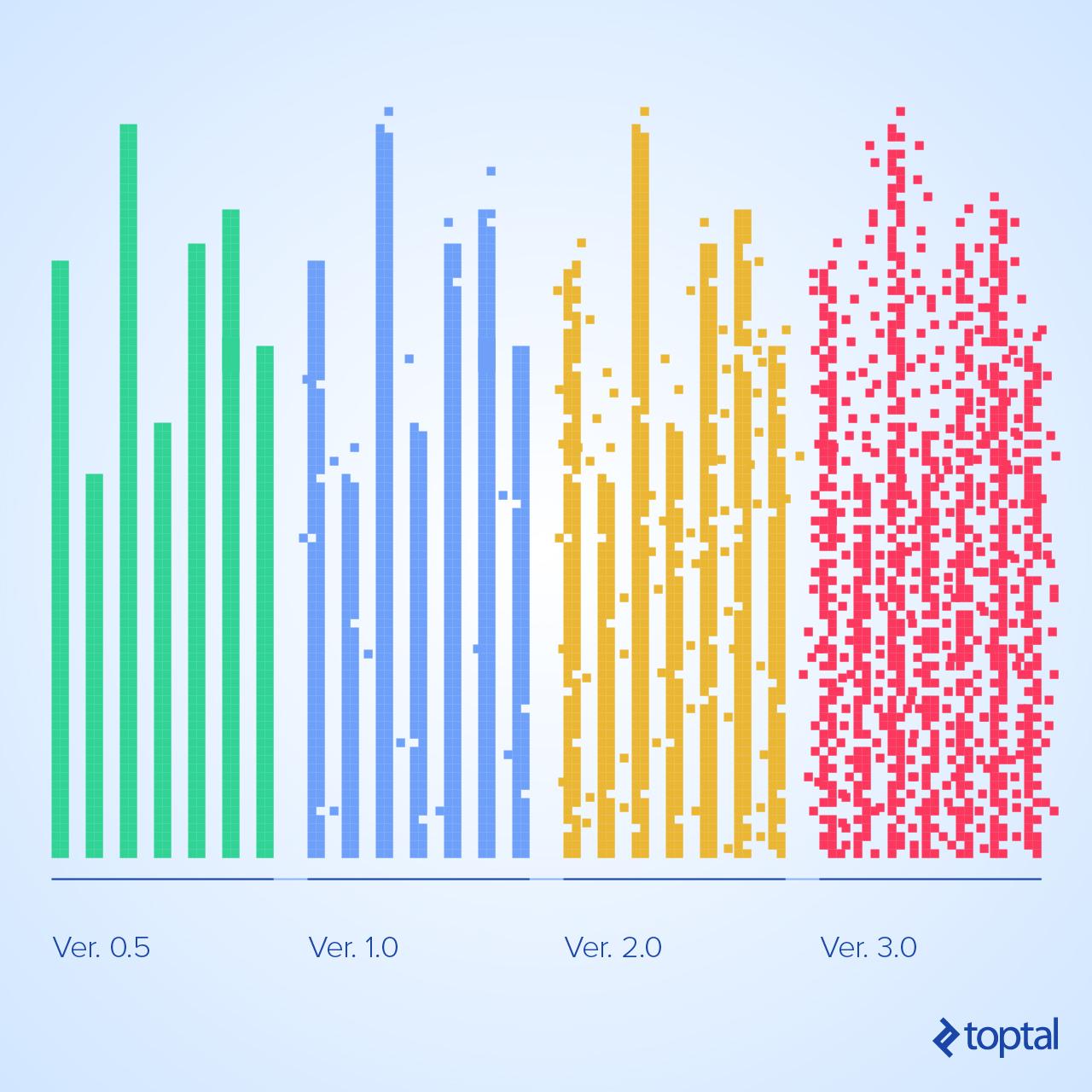

We aim to raise awareness of software entropy as it affects all software development. Additionally, we’ll explore how to assign it a quantifiable value. By measuring software entropy and tracking its growth across releases, we gain a clearer understanding of the risks it presents to current and future endeavors.

What Is Software Entropy?

Software entropy gets its name from a key characteristic of real-world entropy: It represents a degree of disorder that either remains constant or increases with time. Simply put, it measures the inherent instability of a software system when modifications are introduced. While entropy has various interpretations in computer science, the kind we’ll discuss here directly affects development teams and often doesn’t receive the attention it warrants.

Pulling a team member prematurely, initiating a development cycle too early, or implementing “band-aid solutions" are all instances where entropy is likely to escalate, yet it’s rarely considered in these situations.

Software development is a multifaceted craft with vaguely defined fundamental components. Unlike builders who work with tangible materials like cement and nails, software developers work with abstract concepts like logical statements and assumptions. These can’t be physically examined or precisely measured. While superficial comparisons to construction might seem tempting, they’re ultimately unproductive.

Despite these challenges, we can establish guidelines to understand the origins of software entropy, assess its potential impact on our objectives, and if necessary, implement strategies to curb its growth.

We propose the following definition for software entropy:

Here, I´ represents the number of unexpected issues arising from the previous development iteration, C is the perceived likelihood of new changes introducing further issues (I´ > 0), and S is the scope of the upcoming development iteration. Generally, E values below 0.1 are considered positive, 0.5 is deemed high, and values above 1.0 indicate a critical situation.

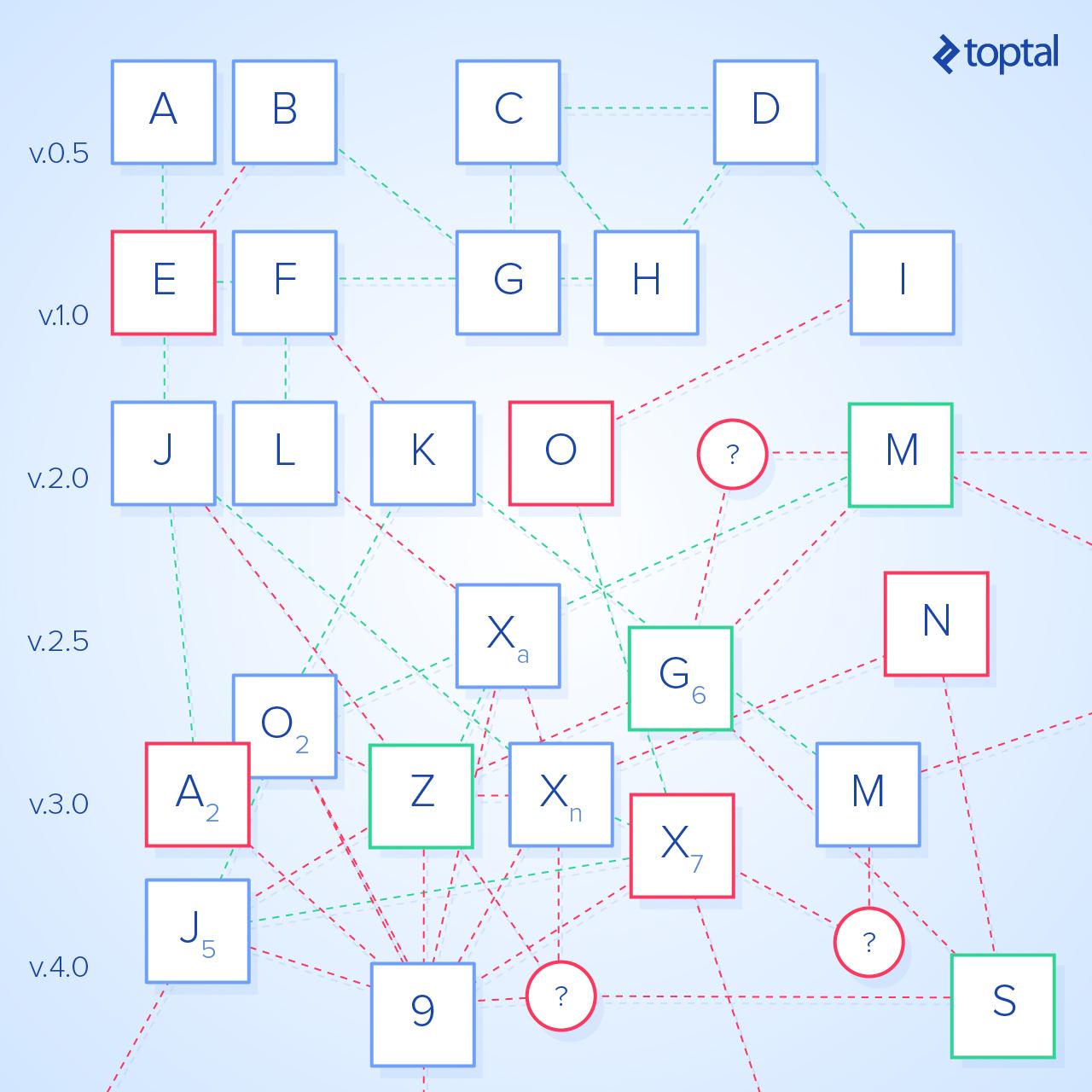

The concept of a development iteration is crucial to understanding software entropy. These cycles transform the system from one state to another. The scope encompasses the goals set for each iteration. In software development, these cycles involve modifying or expanding the underlying codebase.

All code alterations, whether acknowledged or not, occur within a development iteration. Even smaller organizations that develop systems using a “quick and dirty” approach, with minimal planning or analysis, still operate in iterations, albeit unplanned ones. Similarly, if a system’s behavior deviates from expectations after modification, it still resulted from a development iteration.

The risk of such deviations is precisely what understanding software entropy helps us explain, and measuring it allows us to mitigate. Practically speaking, we can define software entropy as follows:

Every system starts with a known set of open issues, I0. After the next development iteration, there will be a new set, I1. Software entropy reflects the likelihood of I1 differing from our expectations and how much this difference might grow in subsequent iterations.

Effects of Software Entropy

Our perception of software entropy’s effects depends on our interaction with the system.

Users have a static perspective; their concern is the current behavior, not the internal workings. They expect specific actions to yield predictable results. However, users are least equipped to gauge the level of entropy in the software they utilize.

Software entropy is intrinsically linked to change and is irrelevant in a static system. Without planned alterations, entropy holds no meaning. Similarly, a non-existent system (where the next iteration is the first) has no entropy.

While users might perceive software as “buggy,” if developers and managers consistently meet their goals in subsequent iterations, the system’s entropy is likely low. Therefore, user experience offers limited insight into software entropy:

Software developers hold a dynamic view. Their focus is on understanding the current functionality for modification purposes and its intricacies for devising appropriate strategies.

Managers have the most intricate perspective, both static and dynamic. They must balance short-term needs with long-term business goals.

Individuals in these roles operate with expectations. Software entropy surfaces when those expectations are unmet. Developers and managers strive to assess and plan for risks, but barring external disruptions, unmet expectations point to software entropy. It’s the unseen force that disrupts unrelated component interactions, causes inexplicable server crashes, and hinders timely and cost-effective solutions.

High-entropy systems often rely heavily on specific individuals, especially if junior team members are present. These individuals possess knowledge that others depend on, knowledge that can’t be easily documented or transferred due to its reliance on experience-based insights and workarounds.

Imagine such an organization manages to stabilize its IT department through significant effort. While any progress seems positive, especially after stagnation, the reality is that expectations have been lowered, and achievements are less ambitious compared to when entropy was low.

Overwhelming software entropy paralyzes projects.

Development iterations cease. However, this doesn’t happen overnight. The decline is gradual, and every system, no matter how well-structured initially, experiences this. Unless proactive measures are taken, entropy and the risk of unforeseen issues will inevitably increase with each iteration.

Software entropy can’t be reversed. Like its real-world counterpart, it only increases or remains constant. Initially, its effects are negligible. As they emerge, the symptoms are subtle and can be easily overlooked. However, addressing software entropy only after it becomes a dominant risk is often futile. Awareness is most beneficial when entropy is low, and its consequences are minimal.

This doesn’t mean every organization should prioritize minimizing entropy. Much software, especially consumer-oriented applications with short lifespans, will likely become obsolete before entropy becomes a significant concern. However, there are less apparent reasons to consider its impact.

Consider software powering critical infrastructure like internet routing or banking transactions. These systems, always in production, demand a low tolerance for unexpected behavior. This risk tolerance – the acceptable level of unforeseen behavior between iterations – is significantly lower than, say, phone routing software, which in turn is lower than that of an e-commerce shopping cart application.

Risk tolerance and software entropy are inherently linked. Minimized entropy ensures that systems stay within their designated risk tolerance during subsequent development iterations.

Sources of Software Entropy

Software entropy stems from a knowledge gap. It’s the divergence between our collective understanding of a system and its actual behavior. This explains why entropy is relevant only when modifying existing systems; it’s the only time this knowledge gap has practical consequences. Entropy thrives in systems where knowledge is scattered across a team, rather than held by an individual. Time, too, is a potent knowledge eraser.

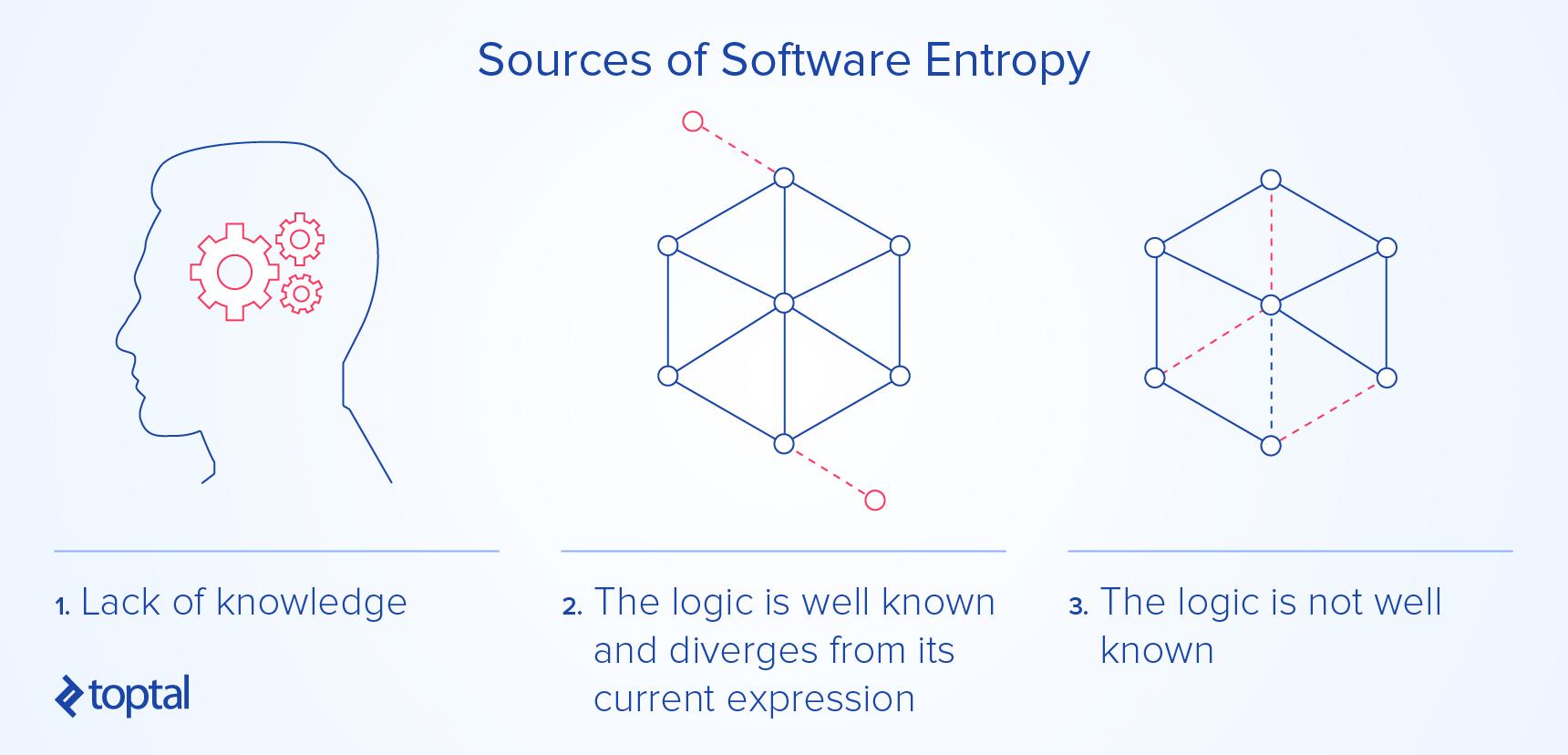

Code embodies logical assertions. When behavior (and consequently, code) deviates from the intended logic, we encounter code entropy. This occurs in three scenarios: The logic is understood but not accurately reflected in the code, there are multiple interpretations of the intended logic, or the logic itself is poorly understood.

The first scenario – understood logic diverging from its implementation – is the easiest to address but the least common. Only very small systems managed by a handful of individuals (e.g., a developer and a stakeholder) might fall into this category.

The second – unclear logic – is rare. Development can hardly begin without a shared understanding among stakeholders. Once achieved, they’re more likely to face the first scenario.

Human minds interpret experiences subjectively, filtering and shaping them to fit personal frameworks. Without effective development practices promoting open communication, mutual respect, and clear expectations, there can be as many interpretations of a system’s workings as there are team members, potentially leading to disagreements about iteration goals.

Many developers, in such situations, reinforce their own understanding of the system and its intended functionality, while managers and stakeholders might inadvertently try to impose their interpretations for their own convenience.

This brings us to the most prevalent source of entropy: Multiple, incomplete understandings of the system’s intended logic. As there’s only ever one manifestation of this logic, this situation is inherently problematic.

How does this knowledge gap arise? Incompetence is one factor, as is a lack of consensus on iteration goals. However, other elements contribute. Organizations might nominally adopt a development methodology but then inconsistently apply its principles, leading to vaguely defined tasks open to interpretation. This is particularly common during methodology transitions, but not exclusive to them. Unresolved personal conflicts within the team can further exacerbate the disconnect between expectations and outcomes.

Another significant contributor to knowledge loss is transfer. Documenting technical knowledge is challenging, even for skilled writers. Choosing what to document is as crucial as how. Without discipline, documentation becomes bloated or omits crucial details due to faulty assumptions. Additionally, maintaining its accuracy poses a challenge for many organizations. Consequently, knowledge transfer often relies on pairing or other forms of direct human interaction.

Entropy experiences significant spikes when active team members depart, taking valuable knowledge with them. Replicating this knowledge is impossible, and even approximating it requires considerable effort. However, with dedicated effort and resources, sufficient knowledge can be preserved to minimize entropy growth.

Other sources of software entropy exist, but are relatively less impactful. Software rot, for example, refers to unexpected system behavior due to environmental changes. This could involve reliance on evolving third-party libraries, but also more subtle changes in underlying assumptions. A system designed with certain memory constraints might start malfunctioning unexpectedly if those constraints are no longer met.

How to Calculate Entropy: Assigning Values to C, S, and I

I represents the number of unresolved behavioral issues, including missing features, in a software system. This is a known quantity often tracked in systems like JIRA. I´ is derived directly from I, representing the sum of “work units” abandoned or left unfinished in the previous iteration, plus those stemming from new and unexpected issues. Expressing I´ in work units allows us to relate it to S, the next iteration’s scope, measured in the same units. The definition of a “work unit” depends on the specific development methodology.

C represents the perceived probability that, after implementing the scoped work units, the actual number of open issues (I1) will exceed the current estimation. This value ranges from 0 to 1.

One might argue that C itself represents software entropy. However, there’s a fundamental difference. C is a perceived probability, not an absolute value. Nevertheless, it’s a useful indicator as the team’s sentiment offers valuable insight into the project’s stability.

The scope, S, considers the magnitude of proposed changes and must be expressed in the same units as I´. A larger S generally corresponds to lower entropy because we’re broadening the change scope. While this might seem counterintuitive, remember that entropy measures the likelihood of development not meeting expectations. It’s not just about introducing new problems. We naturally anticipate and incorporate risks into our planning (and thus, our estimation of I1, which might increase). Higher confidence in tackling a larger scope indicates lower system entropy – unless the individuals involved are incompetent, which would likely be reflected in the current I´ value.

Note that we needn’t quantify the difference between the actual I1 and its estimated value. Assuming our plans are sound, predicting the degree of deviation is unreasonable. We can only estimate the probability (C) of it happening. However, this difference (I1 actual vs. expected) becomes crucial for calculating entropy in the next iteration, influencing the I´ value.

Theoretically, I´ could be negative, but this is practically impossible; we don’t usually solve problems accidentally. Negative I´ values should raise concerns about the entropy calculation method itself. While specific measures can reduce entropy growth (as discussed later), I´ shouldn’t be negative as we incorporate our expectations into our designs.

C is subjective, residing in the minds of the development team. It can be gauged through anonymous team polls, with results averaged for a representative value. Frame the question positively. For example: “On a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being most likely, how confident are you that the team will achieve all its goals this iteration?”

Focus on the overall objectives, not individual tasks. A response of 10 translates to C = 0, while 7 indicates C = 0.3. In larger teams, weigh each response based on factors like experience and time commitment to the project, but not perceived competence. Even junior members develop a sense of the team’s effectiveness. Consider discarding outlier values (highest and lowest) before averaging.

While asking professionals about their team’s likelihood of failure can be sensitive, it’s essential for quantifying entropy. Ensure anonymity and a safe environment for honest answers, even if they reflect poorly on the project.

S must be expressed in the same “work units” as I´, making it heavily dependent on the development methodology. For teams using Agile methodologies, “stories” naturally fit as the “work unit” for both S and I´. Here, a development iteration spans each scheduled release, minor or major. I´ becomes the sum of stories incomplete by the release and those added due to unexpected post-release issues.

However, this approach requires accounting for the discovery and analysis phase before breaking down bugs into stories. This means the true I´ value is only available after a delay. Additionally, polling for C typically occurs at the start of each sprint, necessitating averaging over the release cycle. Despite these challenges, teams using Agile will likely find “stories” the most accurate unit for quantifying S (and consequently, I´).

Regardless of the methodology, the principles remain constant: measure software entropy between releases, use consistent “work units” for S and I´, and gather anonymous C estimates from the team in a non-threatening environment.

Reducing the Growth of E

Lost knowledge about a system is irrecoverable, making entropy reduction impossible. The best we can do is control its growth.

Appropriate development practices can help limit entropy growth. Pair programming, integral to Agile, is particularly beneficial. By involving multiple developers during code creation, essential knowledge is distributed, mitigating the impact of team member departures.

Well-structured and accessible documentation is another valuable practice, especially in waterfall methodologies. This requires well-defined and universally understood documentation standards. Organizations relying heavily on documentation for knowledge management are well-suited for this approach. Conversely, its value diminishes in the absence of clear guidelines and training, which is often the case in younger organizations favoring RAD or Agile methodologies.

There are two primary avenues for limiting entropy growth: reducing I´ or reducing C.

The former involves refactoring, addressing technical debt. Actions targeting I´ often involve technical improvements and are likely familiar to developers. This necessitates a dedicated development iteration where the focus is solely on reducing entropy growth, without delivering immediate business value, and consuming time and resources. This often makes it a hard sell within organizations.

Reducing C offers a more potent and long-term solution. Additionally, C acts as a crucial check on the I´ to S ratio. Actions targeting C often focus on human behavior and mindset. While they might not necessitate a separate development iteration, they will impact subsequent iterations as the team adapts to new procedures. Even seemingly simple tasks, like agreeing on necessary improvements, can be challenging as they expose the diverse goals of stakeholders and team members.

Wrapping Up

Software entropy represents the risk of encountering unexpected problems, unmet objectives, or both when modifying existing software.

While initially negligible, it grows with each development iteration. Left unchecked, it can bring development to a standstill.

However, not all projects need to be overly concerned with entropy. Many systems will reach their end-of-life before entropy significantly impacts them. For longer-lived systems where entropy poses a genuine threat, early awareness and measurement, while it’s still manageable, can help ensure continued development.

Once software entropy overwhelms a system, further modifications become impossible, effectively ending its development lifecycle.