Editor’s note: This article was updated on 5/1/23 by our editorial team. It has been modified to include recent sources and to align with our current editorial standards.

When examining various methods of evaluating software engineer performance, a common question arises: Why are multiple review models necessary? The straightforward answer is that software development is an intricate, multifaceted process, often involving numerous individuals collaborating across different teams.

Executives and stakeholders might not possess detailed knowledge about each developer’s qualifications and responsibilities, especially within large organizations. Consequently, performance evaluations should be entrusted to technically skilled professionals who comprehend each software engineer’s responsibilities, proficiencies, skills, and overall role in the software development lifecycle.

So, what constitutes an effective software developer performance review? The answer hinges on factors like organization size and objectives, along with specific aspects of an engineer’s work.

Management Performance Reviews

Managers are instrumental in engineering performance evaluations. In smaller organizations, a direct manager might be the sole reviewer. However, larger companies often employ more intricate review processes, involving multiple individuals across various roles and departments. These organizations also tend to utilize peer reviews and self-assessments more frequently.

Performance reviews have significantly evolved since their widespread adoption by major corporations in the latter half of the 20th century. However, the history of performance reviews falls outside this article’s purview, as does the behavioral psychology underpinning certain performance review models. Instead, this piece concentrates on the practical aspects of the process, commencing with management’s responsibilities.

While approaches may differ based on organizational size and type, fundamental principles apply to most review scenarios.

How Managers Should Approach Performance Reviews

Management must meticulously plan the review process, ensuring all participants understand their roles.

- The review process should be established well in advance, providing managers and engineers sufficient time for participation and feedback submission. Last-minute feedback may be less valuable due to potential haste in meeting deadlines.

- Management must effectively communicate the goals, objectives, and significance of the review process to engineers and relevant stakeholders. Transparent communication can alleviate apprehensions and enhance review quality.

- Review templates or forms should be mutually agreed upon beforehand, designed for long-term use. Ideally, these should remain consistent across review cycles to ensure result comparability over time.

- The methodology should aim to minimize bias and guarantee consistency. While individual preferences exist, consistent practices prevent undue influence from personal biases on outcomes.

- When incorporating peer reviews and self-assessments, management must uphold the review process’s integrity.

Mitigating Bias and Addressing Questionable Performance Reviews

Given management’s significant influence on the review process, they must be cognizant of potential biases and other factors that could undermine it. Even with meticulous planning and a well-structured process, management might need to address undesirable practices and ensure fairness.

- Competencies and expectations should be considered throughout the process. A one-size-fits-all approach can lead to overly positive or negative reviews. If a peer submits a questionable review due to unfamiliarity with an engineer’s specific competencies, management should intervene to prevent score distortion.

- Managers can also decline or delegate reviews. For instance, if a manager lacks direct involvement with a small team, they should delegate the review to someone more familiar with the team’s work.

- Reviewers lacking in-depth knowledge about an individual or their tasks might submit superficial reviews merely for completion.

- Biased reviews can skew results. Managers might harbor biases, consciously or unconsciously, influencing their objectivity. Similarly, reviewers might selectively highlight specific performance indicators to present a skewed perspective.

Ideally, managers and executives would conduct reviews objectively, but recognizing inherent biases can help mitigate their impact.

Remember, a manager’s review approach can reveal insights into their own performance and professionalism.

Software Engineer Peer Performance Reviews

Peer reviews offer distinct advantages over manager reviews, although some trade-offs exist.

Peers, being more familiar with each other’s work, are often better positioned to evaluate performance. They collaborate on projects, interact frequently, and possess insights into team dynamics and individual capabilities.

However, bias can also influence peer reviews. Positive bias can stem from friendships, while negative bias can arise from personal conflicts or rivalries. Groupthink can also occur, particularly in close-knit teams, where individuals might hesitate to criticize teammates. Therefore, peer review templates and questionnaires should be designed to minimize bias, emphasizing specific competencies and objective criteria. Focusing on how team members align with key performance indicators generally provides more value than subjective questions about personality traits.

The potential for bias raises a crucial question: Should peer reviews be anonymous?

Valid arguments support both anonymous and public reviews. However, organizational structures and team sizes must be considered. While there’s no definitive answer, most organizations lean towards anonymous reviews.

Anonymous vs. Public Feedback

Let’s examine the merits of anonymous feedback:

- Anonymity can foster openness and originality. Dissenting opinions might be suppressed in environments where a majority holds a particular view. Anonymous reviews allow for diverse perspectives without interpersonal repercussions.

- Anonymous feedback can uncover valuable information. Individuals compiling feedback might prioritize insights from anonymous sources over public ones, revealing issues that might otherwise go unnoticed.

- Preserving relationships is crucial. Anonymity helps maintain team cohesion by mitigating potential friction arising from negative feedback.

- Anonymous reviews generally see higher participation rates, especially if not mandatory.

However, anonymous peer reviews have drawbacks:

- While promoting candor, anonymity can be misused to further personal agendas through dishonest reviews. Individuals might exploit anonymity to undermine colleagues or unfairly favor others.

- Public reviews often carry more weight. Feedback from a respected teammate tends to have a greater impact than anonymous feedback.

- Ensuring anonymity is challenging in small organizations. Individuals can often deduce reviewers’ identities, rendering anonymity ineffective.

- Public reviews, while potentially harder to solicit, encourage reviewers to be more diligent and objective, knowing their names are attached.

Self-Assessments

Self-assessments, or self-appraisals, are another common performance review method, often surrounded by debate.

Managers typically request regular self-assessments from employees to track progress. While monthly appraisals are less common, annual, biannual, and quarterly self-assessments are frequently employed. Regular feedback from software engineers, especially those operating with significant autonomy, can be beneficial. These assessments allow engineers to highlight potential issues, explain how they overcame challenges, detail performance improvements, and identify obstacles hindering further growth.

Mitigating the Limitations of Self-Assessments

Self-assessments, however, possess inherent limitations, primarily bias. Individuals might overstate their accomplishments, downplay shortcomings, or attribute performance issues to external factors. Conversely, some might be overly critical. Both scenarios can lead to skewed results.

Organizations can mitigate these shortcomings by designing self-assessment forms and questions that minimize bias:

- Avoid open-ended questions that allow for excessive subjectivity.

- Focus on tangible outcomes instead of subjective goals.

- Prioritize critical responsibilities handled by the reviewee.

- Emphasize key performance indicators and quantifiable targets.

- Reinforce organizational values and assess performance accordingly.

Including a comments section allows engineers to address any issues not covered in the form.

360-degree Assessments

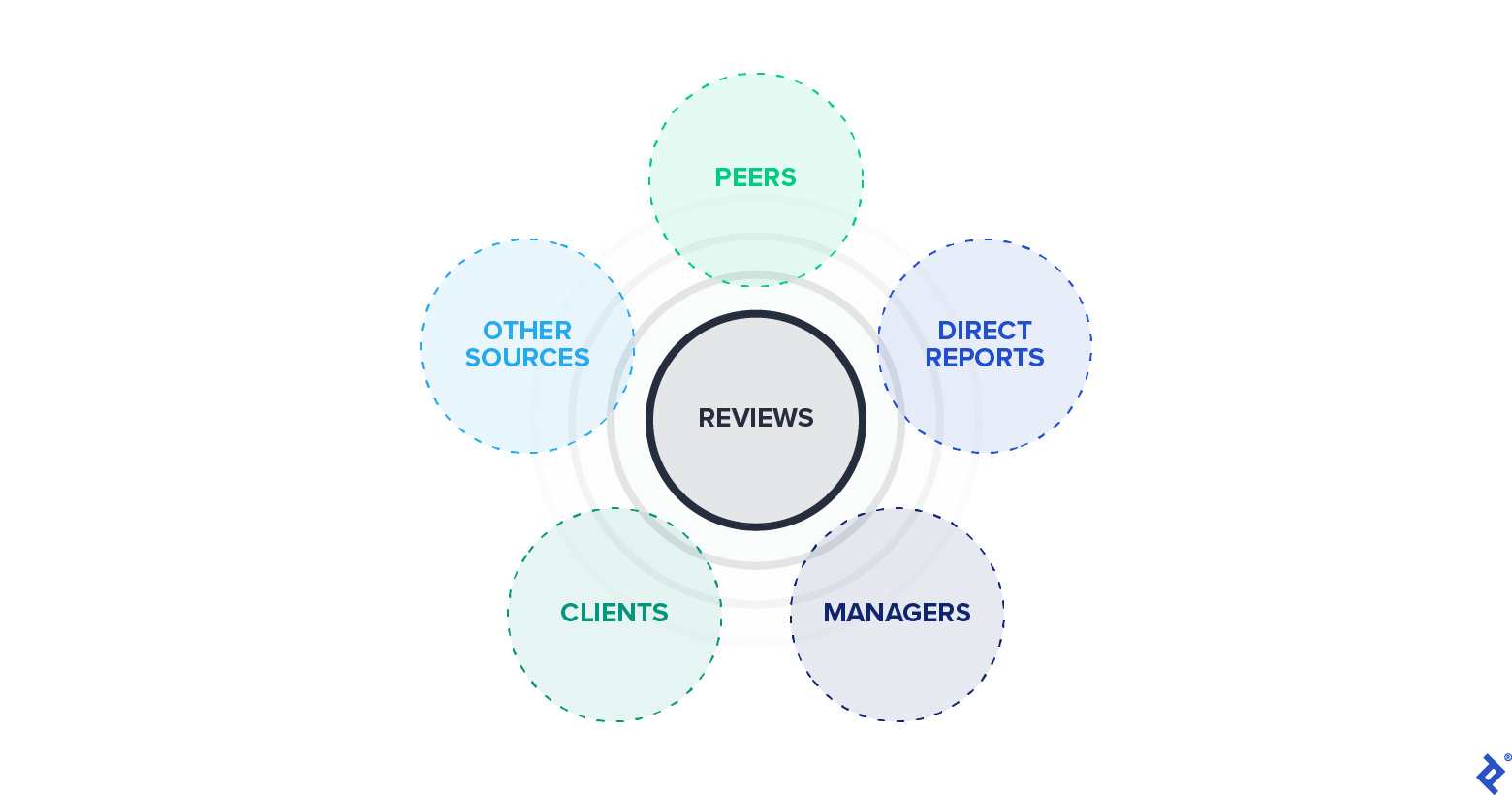

A 360-degree feedback process consolidates previously discussed models to gather comprehensive feedback, identifying strengths and weaknesses. This approach involves collecting input from various sources, such as direct performance reviews, peer reviews, manager reviews, client feedback, and other relevant perspectives. These are then compiled into a single, easily digestible report for the reviewee.

This method, by gathering feedback from multiple sources and encompassing more than just basic performance indicators, proves useful in numerous situations. It provides a holistic view of an engineer’s performance. While organizations might choose not to share individual review results with employees, the aggregated 360-degree feedback can be shared.

This approach assesses teamwork skills and gathers feedback on an engineer’s performance, conduct, communication, and other desired criteria. However, it might not be ideal for evaluating technical skills, particularly those specific to a particular project. Since it involves individuals with varying levels of familiarity with the reviewee, 360-degree feedback might lack the nuance to assess certain aspects of a software engineer’s performance.

What to Include in Software Engineer Performance Reviews

What should a valuable and actionable developer performance review encompass? Should it be comprehensive or focus on a few areas for immediate improvement?

The answer depends on organizational needs and review scope. However, certain elements should be standard in most performance reviews.

Speed and Iteration

A developer’s task completion speed is a crucial metric, as is their approach to iterative software development. Speed and iteration are vital when working with large teams on a single project, individuals frequently switching between projects, and urgent tasks. An engineer’s ability to contribute rapidly can significantly impact project success.

Code Quality and Code Reviews

While speed is important, it shouldn’t compromise code quality. Subpar code can create future problems for the team or organization.

A code review involves someone scrutinizing another person’s code. This process, while time-consuming, is straightforward and ensures quality maintenance. Ongoing code reviews alleviate the need to review every line of code. Code reviewers should be skilled individuals capable of identifying issues related to design, functionality, style, and documentation.

Professional Communication

Effective communication is crucial for software engineers. They regularly interact with peers, team leads, stakeholders, and clients, necessitating professionalism and responsibility.

Poor communication can hinder work quality and escalate minor issues into major problems. For engineers working directly with clients, communication breakdowns can jeopardize projects.

Professional and timely communication is paramount and should be reviewed. Even exceptional technical skills cannot compensate for poor communication.

Recruitment, Leadership, and Planning

Senior software engineers and team leads often contribute to recruitment, making it essential to evaluate their performance in this area. Poor recruitment decisions have cascading effects on the team and organization.

Leadership can be challenging to assess, especially if team members are hesitant to provide negative feedback. The review process should safeguard them from potential repercussions for providing honest feedback about their superiors.

Planning is another subjective area. Leaders should ensure adequate planning and execution of team goals. However, their performance in this domain relies on other team members. While missed targets and deadlines raise concerns, the review process should consider contributing factors like inadequate management support or resource constraints.

Performance Reviews Aren’t Easy—Don’t Make Them Harder

Each organization should tailor its performance review model to its specific needs. Practices effective for one company might not translate well to another.

Performance reviews demand significant planning and consideration. Striking a balance between comprehensiveness, practicality, and usefulness is essential. Smaller organizations can conduct effective performance reviews without excessive complexity. Similarly, larger organizations should strive for streamlined processes.

Remember to review the review process itself. Before initiating the next review cycle, assess the effectiveness of the previous one. Did it run smoothly? Did it yield valuable insights? Identify and address any shortcomings to continuously improve the process.