Bjarne Stroustrup’s book, The C++ Programming Language, features a chapter called “A Tour of C++: The Basics - Standard C++”. Section 2.2 of this chapter briefly touches on the compilation and linking processes in C++. These processes are fundamental to C++ software development, yet surprisingly, many C++ developers don’t fully grasp them.

Have you ever wondered why C++ source code is divided into header and source files? How does the compiler interpret each part? What are the implications for compilation and linking? These are just a few of the questions you might have pondered but eventually accepted as standard practice.

Understanding the intricacies of compilation and linking can be incredibly beneficial, whether you’re designing a C++ application, adding new features, troubleshooting bugs (especially those that seem strange), or integrating C and C++ code. This article will equip you with that knowledge.

We’ll delve into the workings of a C++ compiler, examining basic language constructs, addressing frequently asked questions about these processes, and helping you avoid common pitfalls encountered during C++ development.

Note: Example source code accompanying this article is available for download from https://bitbucket.org/danielmunoz/cpp-article

These examples were compiled on a CentOS Linux system with the following specifications:

| |

The g++ compiler version used is:

| |

While the provided source files should be compatible with other operating systems, the accompanying Makefiles for automated building are likely to be compatible only with Unix-like systems.

The Build Pipeline: Preprocessing, Compilation, and Linking

Every C++ source file must undergo compilation to produce an object file. These object files, generated from compiling multiple source files, are then linked together to create an executable, a shared library, or a static library (which is essentially an archive of object files). C++ source files typically have extensions like .cpp, .cxx, or .cc.

A C++ source file can incorporate other files known as header files using the #include directive. Header files usually have extensions like .h, .hpp, or .hxx, or sometimes no extension at all, as seen in the C++ standard library and other libraries like Qt. The extension is irrelevant to the C++ preprocessor, which simply replaces the line containing the #include directive with the entire contents of the included file.

The initial step the compiler takes when processing a source file is to run the preprocessor on it. It’s important to note that only source files are directly handled by the compiler for preprocessing and compilation. Header files are not passed to the compiler directly but are included from within source files.

During the preprocessing phase, each header file can be opened numerous times, depending on how many source files include it, or how many other header files included by those source files also include it (resulting in multiple layers of indirection). In contrast, source files are only opened once by the compiler (and preprocessor) when they are directly passed in.

For every C++ source file, the preprocessor constructs a translation unit. This involves inserting content from included files when it encounters an #include directive, while simultaneously removing code from both the source file and headers when it encounters conditional compilation blocks whose directives evaluate to false. Additionally, it performs other tasks tasks such as macro replacements.

Once the preprocessor finishes creating the (often quite large) translation unit, the compiler initiates the compilation phase, ultimately generating the object file.

To examine the translation unit (the preprocessed source code), the -E option can be passed to the g++ compiler along with the -o option to specify the desired filename for the preprocessed output.

In the cpp-article/hello-world directory, you’ll find an example file named “hello-world.cpp”:

| |

To generate the preprocessed file, use the following command:

| |

You can then check the number of lines in the output:

| |

On my system, it has 17,588 lines. Alternatively, you can simply run make in the directory, which will automate these steps.

As you can see, the compiler often has to handle a much larger file than the simple source file we initially wrote. This is a direct result of included headers. In our example, we only included a single header. The translation unit grows as we include more headers.

This preprocess and compile process is quite similar in C. It adheres to C’s compilation rules, and the way it includes header files and generates object code is almost identical.

How Source Files Import and Export Symbols

Let’s now examine the files located in the cpp-article/symbols/c-vs-cpp-names directory.

Consider a basic C (not C++) source file called sum.c that exports two functions: one for adding two integers and another for adding two floats:

| |

Compile this file (or use make to build both example applications for execution) to create the sum.o object file:

| |

Now, let’s inspect the symbols exported and imported by this object file:

| |

As you can see, no symbols are imported, while two symbols are exported: sumF and sumI. These symbols are exported within the .text segment (T), indicating that they are function names, or executable code.

If other source files (whether C or C++) need to call these functions, they must be declared before use.

The standard approach is to create a header file containing their declarations and include it in any source file where those functions need to be called. The header file’s name and extension are arbitrary. For this example, I’ve chosen sum.h:

| |

What purpose do those ifdef/endif conditional compilation blocks serve? When this header is included from a C source file, we want it to become:

| |

However, when included from a C++ source file, it should transform into:

| |

The C language has no concept of extern "C" directive, but C++ does. This directive is necessary when declaring C functions in C++ because C++ mangles function (and method) names to support function/method overloading, a feature absent in C.

This can be observed in the C++ source file named print.cpp:

| |

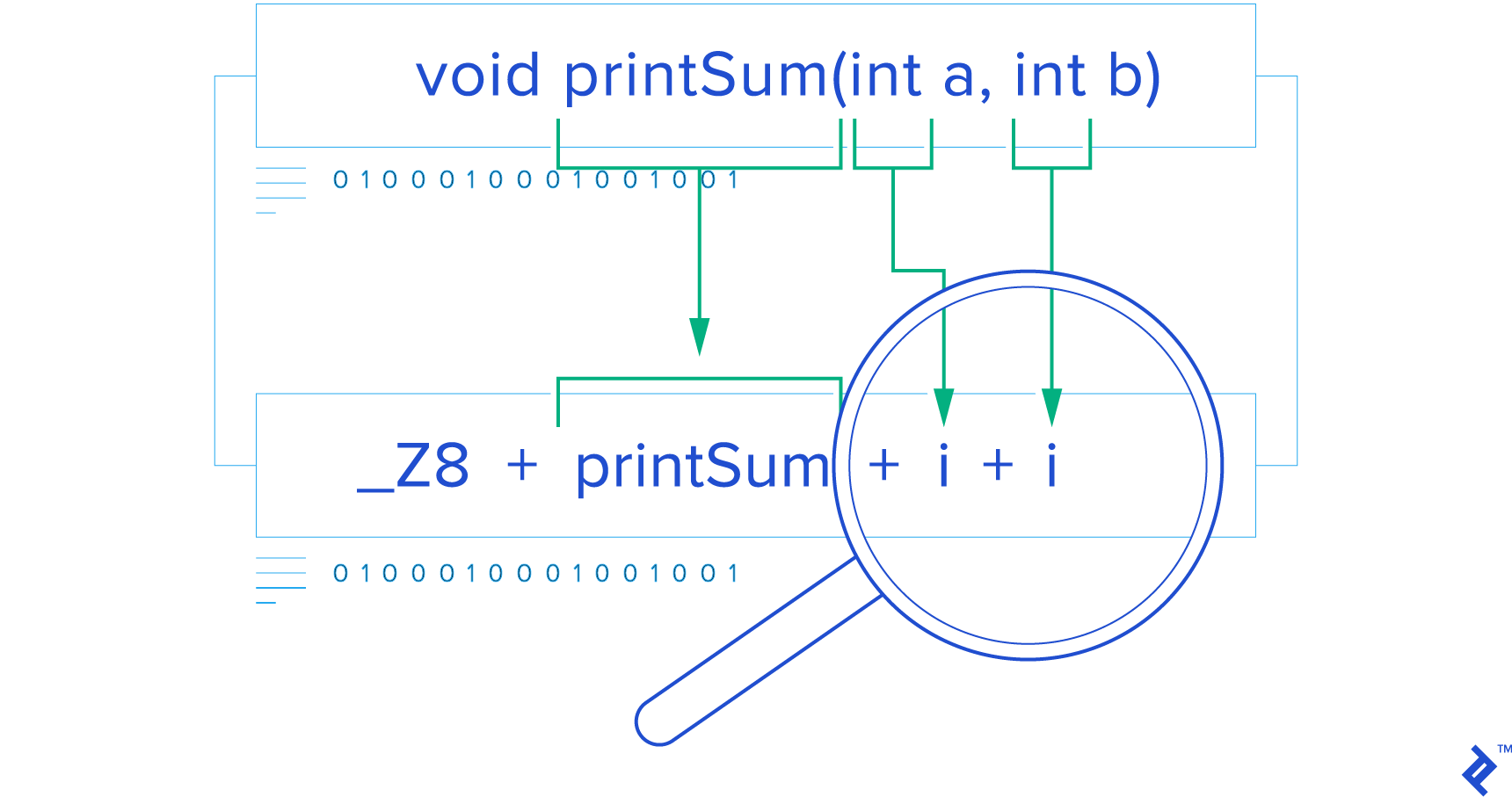

This file defines two functions with the same name (printSum), differentiated only by their parameter types: int or float. This demonstrates Function overloading is a C++ feature a concept not found in C. To implement this and distinguish between these functions, C++ uses name mangling, as evident in their exported symbol names (I’ll only highlight the relevant parts of the nm output):

| |

These functions are exported (on my system) as _Z8printSumff for the float version and _Z8printSumii for the int version. In C++, every function name undergoes mangling unless explicitly declared as extern "C".

In print.cpp, two functions, printSumInt and printSumFloat, are declared with C linkage. Consequently, they cannot be overloaded as their exported names would be identical without mangling. To differentiate them, I had to append “Int” or “Float” to their names.

Because they are not mangled, these functions can be called directly from C code, as we’ll see shortly.

To view the mangled names in a more human-readable format, similar to how they appear in C++ source code, we can use the -C (demangle) option with the nm command. Again, I’ll only display the relevant portion of the output:

| |

With this option, instead of _Z8printSumff, we see printSum(float, float), and instead of _ZSt4cout, we see std::cout, which are more understandable representations.

We can also observe that our C++ code is calling C code: print.cpp calls sumI and sumF, which are C functions declared with C linkage in sum.h. The nm output for print.o confirms this by listing undefined (U) symbols: sumF, sumI, and std::cout. These undefined symbols are expected to be provided by one of the object files (or libraries) that will be linked together with this object file during the linking phase.

Keep in mind that up to this point, we’ve only compiled source code into object code; we haven’t performed any linking yet. If we don’t link the object file containing the definitions for those imported symbols with this object file, the linker will halt with a “missing symbol” error.

It’s important to note that since print.cpp is a C++ source file compiled with a C++ compiler (g++), all its code is treated as C++ code, even functions with C linkage like printSumInt and printSumFloat. They are still C++ functions that can utilize C++ features. The only aspect compatible with C is their symbol names. The code itself remains C++, evident from the fact that both functions call an overloaded function (printSum), which would be impossible if printSumInt or printSumFloat were compiled as pure C.

Let’s now examine print.hpp, a header file designed for inclusion from both C and C++ source files. This allows printSumInt and printSumFloat to be called from either language, while restricting printSum to C++:

| |

When included from a C source file, we only want to expose:

| |

printSum remains hidden from C code due to its mangled name, so there’s no standard or portable way to declare it for C. While I could technically declare them as:

| |

This would satisfy the linker since those are the exact names generated by my current compiler. However, there’s no guarantee it will work with your linker (if your compiler uses a different mangling scheme) or even with future versions of my linker. Furthermore, the call itself might not behave as expected due to potential differences in calling conventions (how parameters are passed and return values are handled). These conventions can be compiler-specific and may differ between C and C++ calls, particularly for C++ member functions that receive the this pointer as a parameter.

Your compiler might employ one calling convention for regular C++ functions and a different one for those declared with extern "C" linkage. Consequently, misleading the compiler by claiming a function uses the C calling convention when it actually uses the C++ convention could lead to unexpected behavior if the conventions differ in your specific toolchain.

There are standard ways to mix C and C++ code, and the standard, reliable way to invoke overloaded C++ functions from C is to wrap them in functions with C linkage which is what we accomplished by wrapping printSum with printSumInt and printSumFloat.

When print.hpp is included from a C++ source file, the __cplusplus preprocessor macro is defined, and the file is interpreted as:

| |

This enables C++ code to call the overloaded printSum function or its wrappers, printSumInt and printSumFloat.

Now, let’s create a C source file containing the main function, which serves as the entry point for our program. This C main function will call printSumInt and printSumFloat, essentially invoking both C++ functions that have C linkage. Remember, these are still C++ functions (their bodies execute C++ code); they simply lack C++ mangled names. We’ll name this file c-main.c:

| |

Let’s compile it to generate the object file:

| |

And examine its imported/exported symbols:

| |

As anticipated, it exports main and imports printSumFloat and printSumInt.

To link everything together into an executable, we need to use the C++ linker (g++) because at least one file, print.o, was compiled as C++:

| |

Executing the resulting executable produces the expected output:

| |

Now, let’s try the same with a C++ main file named cpp-main.cpp:

| |

After compiling, let’s inspect the imported/exported symbols of the cpp-main.o object file:

| |

It exports main and imports the C linkage functions printSumFloat and printSumInt, as well as both mangled versions of printSum.

You might be wondering why the main symbol isn’t mangled, such as main(int, char**), in this C++ source file despite not being explicitly declared as extern "C". Well, main is a special implementation defined function and my particular compiler implementation seems to default to C linkage for it regardless of whether it’s defined in a C or C++ source file.

Linking and running this program also yields the expected output:

| |

How Header Guards Work

Up until this point, I’ve been careful to avoid including headers multiple times, either directly or indirectly, within the same source file. However, since one header can include others, it’s possible for the same header to be included multiple times indirectly. Since header content is directly inserted at the point of inclusion, this can easily lead to duplicate declarations.

Let’s illustrate this with the example files in the cpp-article/header-guards directory.

| |

The crucial difference lies in guarded.hpp, where the entire header is enclosed within a conditional block that’s only included if the __GUARDED_HPP preprocessor macro is not defined. The first time the preprocessor encounters this file, the macro won’t be defined. However, because the macro is defined within the guarded code, the next time it’s included (from the same source file, directly or indirectly), the preprocessor will recognize the lines between #ifndef and #endif and discard everything in between.

It’s essential to understand that this process occurs for every source file being compiled. This means a header file can be included once and only once per source file. The fact that it was included in one source file doesn’t prevent it from being included in another; it merely prevents multiple inclusions within the same source file.

The example file main-guarded.cpp includes guarded.hpp twice:

| |

However, the preprocessed output only contains a single definition of class A:

| |

Consequently, it compiles without any issues:

| |

In contrast, the main-unguarded.cpp file includes unguarded.hpp twice:

| |

And the preprocessed output reveals two definitions of class A:

| |

This will undoubtedly cause compilation problems:

| |

Specifically, in the file included from main-unguarded.cpp:2:0:

| |

For the sake of brevity, I won’t be using header guards in the remaining examples unless absolutely necessary since most are short and self-contained. However, it’s crucial to always guard your header files in real-world projects. Remember, this only applies to header files, not source files, as source files are not designed to be included elsewhere.

Pass by Value and Constness of Parameters

Let’s analyze the by-value.cpp file in the cpp-article/symbols/pass-by directory:

| |

By using the using namespace std directive, I can avoid having to qualify the names of symbols (functions or classes) within the std namespace throughout the rest of the translation unit, which in this case is the remainder of the source file. However, it’s generally discouraged to use this directive in header files. Since a header file is meant to be included by multiple source files, this directive would bring the entire std namespace into the global scope of each including file from the point of inclusion onwards.

Even headers included after mine in those files would then have those symbols in scope. This can lead to name clashes, as they wouldn’t be expecting those symbols to be present. Therefore, avoid using this directive in header files. It’s acceptable to use it in source files, but only after all headers have been included.

Observe how some parameters are declared as const. This indicates that they cannot be modified within the function’s body; any attempt to do so would result in a compilation error. Additionally, note that all parameters in this source file are passed by value, not by reference (&) or by pointer (*). This implies that the caller makes a copy of the arguments and passes those copies to the function. Consequently, the const qualifier on parameters passed by value has no bearing on the caller because any modifications made to the parameters within the function’s body only affect the copies, not the original values passed by the caller.

Since the const-ness of a parameter passed by value is inconsequential to the caller, it’s not reflected in the mangled function signature, as evident from inspecting the compiled object code (showing only the relevant output):

| |

The signatures don’t indicate whether the copied parameters are const or not within the function bodies because it simply doesn’t matter. The const qualifier in the function definition only serves as a visual cue to anyone reading the function’s code, clarifying whether those values are ever modified. In our example, only half of the parameters are declared as const to highlight the difference. However, for the sake of const-correct they should all be declared as such since none are modified within the function (and they shouldn’t be).

Since this distinction is irrelevant in the function declaration, which is what the caller sees, we can define the by-value.hpp header like so:

| |

While adding the const qualifiers here is allowed (you can even mark variables as const in the declaration even if they aren’t in the definition, and it will compile), it’s not necessary and only adds unnecessary verbosity to the declarations.

Pass by Reference

Let’s shift our attention to by-reference.cpp:

| |

When passing by reference, const-ness becomes crucial to the caller because it dictates whether the passed argument can be modified by the called function. Therefore, the exported symbols accurately reflect their const-ness:

| |

This information must also be reflected in the header file that callers will use:

| |

You might have noticed that I omitted the variable names in the declarations (within the header), which is perfectly legal in this example and the previous ones. Variable names aren’t mandatory in declarations because the caller doesn’t need to know how you choose to name your variables internally. However, it’s generally considered good practice to include parameter names in declarations so that users of the function can readily understand the purpose of each parameter and what values to pass.

Interestingly, variable names are also optional in the function definition itself. They are only required if the parameter is actually used within the function body. If a parameter is never used, you can omit its name in the definition, leaving only the type. Why would a function declare a parameter it never uses? Sometimes functions (or methods) are part of an interface, like a callback interface, where the interface dictates specific parameters that must be passed to the observer. The observer is obligated to provide a callback function that accepts all parameters specified by the interface because the caller will be sending them. However, the observer might not be interested in all of them. To avoid compiler warnings about “unused parameters,” the function definition can omit the names of unused parameters.

Pass by Pointer

| |

To declare a pointer to a const element (an int in this example), you can use either of the following notations:

| |

If you also want the pointer itself to be const, meaning the pointer’s value (the address it points to) cannot be changed, add const after the asterisk:

| |

To have a const pointer pointing to a non-const element:

| |

Let’s compare these function signatures with the demangled output from inspecting the object file:

| |

As you can see, the nm tool prefers the first notation (const after the type). Additionally, notice that the only const-ness that’s exported and relevant to the caller is whether the function will modify the element pointed to by the pointer. The const-ness of the pointer itself is inconsequential to the caller because the pointer is always passed as a copy. The function can create its own copy of the pointer and modify it to point elsewhere, which has no impact on the caller.

Therefore, a suitable header file could be:

| |

Passing by pointer shares similarities with passing by reference. One key difference is that when passing by reference, there’s an implicit expectation and assumption that the caller provides a valid reference to an element, not a null pointer or an invalid address. In contrast, pointers can be null or point to invalid memory locations. Pointers are often preferred over references in situations where passing a null pointer has a specific meaning.

Since C++11, values can also be passed using move semantics. However, this topic is beyond the scope of this article but can be explored in resources like Argument Passing in C++.

Another related concept we won’t cover here is how to call all these functions. If all the headers are included in a source file but none of the functions are called, compilation and linking will succeed. However, if you attempt to call all of them, you’ll encounter errors due to ambiguous function calls. The compiler might find multiple matching versions of sum for certain arguments, particularly when deciding between pass-by-value and pass-by-reference (or pass-by-const-reference). Analyzing these scenarios is outside the scope of this article.

Compiling with Different Flags

Let’s now examine a real-world scenario related to this topic that can lead to subtle and hard-to-find bugs.

Navigate to the cpp-article/diff-flags directory and open the Counters.hpp file:

| |

This class defines two counters, both initialized to zero, with methods to increment and read their values. For debug builds, which I’ll define as builds where the NDEBUG macro is not defined, I’ve added a third counter that’s incremented whenever the other two counters are incremented. This serves as a debugging aid for this class. Many third-party libraries and even built-in C++ headers (depending on the compiler) employ similar techniques to enable different levels of debugging. This allows debug builds to detect issues like iterators going out of bounds and other potential problems that the library developers anticipated. I’ll refer to release builds as “builds where the NDEBUG macro is defined.”

In a release build, the preprocessed header would look like this (using grep to remove empty lines):

| |

$ g++ -E Counters.hpp | grep -v -e ‘^

As explained earlier, debug builds have an extra counter.

I’ve also created a few helper files:

| |

| |

| |

And a Makefile to customize the compiler flags specifically for increment2.cpp:

| |

Let’s compile everything in debug mode, without defining NDEBUG:

| |

Now, run the executable:

| |

The output aligns with our expectations. Now, let’s compile just one of the files, increment2.cpp, with NDEBUG defined (simulating a release build) and observe what happens:

| |

The output is unexpected. The increment1 function encountered a release version of the Counters class, which only has two int member fields. It incremented the first field, assuming it was m_counter1, and didn’t touch anything else because it’s unaware of the m_debugAllCounters field. I say increment1 incremented the counter because the inc1 method in Counter is marked as inline, so its code was directly inserted into the increment1 function’s body rather than being called as a separate function. The compiler likely chose to inline it because of the -O2 optimization level flag.

As a result, m_counter1 was never incremented, and m_debugAllCounters was mistakenly incremented in its place by increment1. That’s why we see 0 for m_counter1 but still see 7 for m_debugAllCounters.

In a real-world project I worked on, which involved a large codebase with numerous source files organized into multiple static libraries, we encountered a situation where some libraries were compiled without debugging options enabled for std::vector, while others were compiled with those options enabled.

It’s likely that at some point, all libraries used consistent flags. However, as the codebase grew and new libraries were added, these flags weren’t consistently applied (they weren’t default flags and had to be added manually). We were using an IDE for compilation, and determining the flags used for each library involved navigating through various tabs and windows. This was further complicated by having different (and multiple) sets of flags for different build configurations (release, debug, profile, etc.), making it even harder to notice the inconsistency.

This discrepancy led to crashes in situations where an object file compiled with one set of flags passed a std::vector to another object file compiled with different flags that then performed certain operations on that vector. These crashes were particularly difficult to debug because they only manifested in release builds, not in debug builds (or at least not in the same reproducible manner).

The debugger also behaved erratically because it was trying to debug highly optimized code. To add to the confusion, the crashes were occurring in seemingly correct and straightforward code.

The Compiler Does a Lot More Than You May Think

Throughout this article, we’ve explored some of the fundamental language constructs of C++ and how the compiler interacts with them, from the initial preprocessing stage to the final linking stage. Gaining a deeper understanding of these processes can provide valuable insights into the often-overlooked aspects of C++ development.

From its multi-stage compilation process to the intricacies of function name mangling and generating different function signatures based on context, the C++ compiler diligently works behind the scenes to unlock the power and flexibility of C++ as a compiled programming language.

I hope you find the knowledge gained from this article beneficial in your own C++ endeavors.

1 “Counters.hpp”

1 “”

1 “”

1 “/usr/include/stdc-predef.h” 1 3 4

1 “” 2

1 “Counters.hpp”

class Counters { public: Counters() : m_counter1(0), m_counter2(0) { } void inc1() { ++m_counter1; } void inc2() { ++m_counter2; } int get1() const { return m_counter1; } int get2() const { return m_counter2; } private: int m_counter1; int m_counter2; };

| |

// increment1.hpp: // Forward declaration so I don’t have to include the entire header here class Counters;

int increment1(Counters&);

// increment1.cpp: #include “Counters.hpp”

void increment1(Counters& c) { c.inc1(); }

| |

| |

And a Makefile to customize the compiler flags specifically for increment2.cpp:

| |

Let’s compile everything in debug mode, without defining NDEBUG:

| |

Now, run the executable:

| |

The output aligns with our expectations. Now, let’s compile just one of the files, increment2.cpp, with NDEBUG defined (simulating a release build) and observe what happens:

| |

The output is unexpected. The increment1 function encountered a release version of the Counters class, which only has two int member fields. It incremented the first field, assuming it was m_counter1, and didn’t touch anything else because it’s unaware of the m_debugAllCounters field. I say increment1 incremented the counter because the inc1 method in Counter is marked as inline, so its code was directly inserted into the increment1 function’s body rather than being called as a separate function. The compiler likely chose to inline it because of the -O2 optimization level flag.

As a result, m_counter1 was never incremented, and m_debugAllCounters was mistakenly incremented in its place by increment1. That’s why we see 0 for m_counter1 but still see 7 for m_debugAllCounters.

In a real-world project I worked on, which involved a large codebase with numerous source files organized into multiple static libraries, we encountered a situation where some libraries were compiled without debugging options enabled for std::vector, while others were compiled with those options enabled.

It’s likely that at some point, all libraries used consistent flags. However, as the codebase grew and new libraries were added, these flags weren’t consistently applied (they weren’t default flags and had to be added manually). We were using an IDE for compilation, and determining the flags used for each library involved navigating through various tabs and windows. This was further complicated by having different (and multiple) sets of flags for different build configurations (release, debug, profile, etc.), making it even harder to notice the inconsistency.

This discrepancy led to crashes in situations where an object file compiled with one set of flags passed a std::vector to another object file compiled with different flags that then performed certain operations on that vector. These crashes were particularly difficult to debug because they only manifested in release builds, not in debug builds (or at least not in the same reproducible manner).

The debugger also behaved erratically because it was trying to debug highly optimized code. To add to the confusion, the crashes were occurring in seemingly correct and straightforward code.

The Compiler Does a Lot More Than You May Think

Throughout this article, we’ve explored some of the fundamental language constructs of C++ and how the compiler interacts with them, from the initial preprocessing stage to the final linking stage. Gaining a deeper understanding of these processes can provide valuable insights into the often-overlooked aspects of C++ development.

From its multi-stage compilation process to the intricacies of function name mangling and generating different function signatures based on context, the C++ compiler diligently works behind the scenes to unlock the power and flexibility of C++ as a compiled programming language.

I hope you find the knowledge gained from this article beneficial in your own C++ endeavors.

1 “Counters.hpp”

1 “”

1 “”

1 “/usr/include/stdc-predef.h” 1 3 4

1 “” 2

1 “Counters.hpp”

class Counters { public: Counters() : m_debugAllCounters(0), m_counter1(0), m_counter2(0) { } void inc1() { ++m_debugAllCounters; ++m_counter1; } void inc2() { ++m_debugAllCounters; ++m_counter2; } int getDebugAllCounters() { return m_debugAllCounters; } int get1() const { return m_counter1; } int get2() const { return m_counter2; } private: int m_debugAllCounters; int m_counter1; int m_counter2; };

| |

// increment1.hpp: // Forward declaration so I don’t have to include the entire header here class Counters;

int increment1(Counters&);

// increment1.cpp: #include “Counters.hpp”

void increment1(Counters& c) { c.inc1(); }

| |

| |

And a Makefile to customize the compiler flags specifically for increment2.cpp:

| |

Let’s compile everything in debug mode, without defining NDEBUG:

| |

Now, run the executable:

| |

The output aligns with our expectations. Now, let’s compile just one of the files, increment2.cpp, with NDEBUG defined (simulating a release build) and observe what happens:

| |

The output is unexpected. The increment1 function encountered a release version of the Counters class, which only has two int member fields. It incremented the first field, assuming it was m_counter1, and didn’t touch anything else because it’s unaware of the m_debugAllCounters field. I say increment1 incremented the counter because the inc1 method in Counter is marked as inline, so its code was directly inserted into the increment1 function’s body rather than being called as a separate function. The compiler likely chose to inline it because of the -O2 optimization level flag.

As a result, m_counter1 was never incremented, and m_debugAllCounters was mistakenly incremented in its place by increment1. That’s why we see 0 for m_counter1 but still see 7 for m_debugAllCounters.

In a real-world project I worked on, which involved a large codebase with numerous source files organized into multiple static libraries, we encountered a situation where some libraries were compiled without debugging options enabled for std::vector, while others were compiled with those options enabled.

It’s likely that at some point, all libraries used consistent flags. However, as the codebase grew and new libraries were added, these flags weren’t consistently applied (they weren’t default flags and had to be added manually). We were using an IDE for compilation, and determining the flags used for each library involved navigating through various tabs and windows. This was further complicated by having different (and multiple) sets of flags for different build configurations (release, debug, profile, etc.), making it even harder to notice the inconsistency.

This discrepancy led to crashes in situations where an object file compiled with one set of flags passed a std::vector to another object file compiled with different flags that then performed certain operations on that vector. These crashes were particularly difficult to debug because they only manifested in release builds, not in debug builds (or at least not in the same reproducible manner).

The debugger also behaved erratically because it was trying to debug highly optimized code. To add to the confusion, the crashes were occurring in seemingly correct and straightforward code.

The Compiler Does a Lot More Than You May Think

Throughout this article, we’ve explored some of the fundamental language constructs of C++ and how the compiler interacts with them, from the initial preprocessing stage to the final linking stage. Gaining a deeper understanding of these processes can provide valuable insights into the often-overlooked aspects of C++ development.

From its multi-stage compilation process to the intricacies of function name mangling and generating different function signatures based on context, the C++ compiler diligently works behind the scenes to unlock the power and flexibility of C++ as a compiled programming language.

I hope you find the knowledge gained from this article beneficial in your own C++ endeavors.

1 “Counters.hpp”

1 “”

1 “”

1 “/usr/include/stdc-predef.h” 1 3 4

1 “” 2

1 “Counters.hpp”

class Counters { public: Counters() : m_counter1(0), m_counter2(0) { } void inc1() { ++m_counter1; } void inc2() { ++m_counter2; } int get1() const { return m_counter1; } int get2() const { return m_counter2; } private: int m_counter1; int m_counter2; };

| |

$ g++ -E Counters.hpp | grep -v -e ‘^

As explained earlier, debug builds have an extra counter.

I’ve also created a few helper files:

| |

| |

| |

And a Makefile to customize the compiler flags specifically for increment2.cpp:

| |

Let’s compile everything in debug mode, without defining NDEBUG:

| |

Now, run the executable:

| |

The output aligns with our expectations. Now, let’s compile just one of the files, increment2.cpp, with NDEBUG defined (simulating a release build) and observe what happens:

| |

The output is unexpected. The increment1 function encountered a release version of the Counters class, which only has two int member fields. It incremented the first field, assuming it was m_counter1, and didn’t touch anything else because it’s unaware of the m_debugAllCounters field. I say increment1 incremented the counter because the inc1 method in Counter is marked as inline, so its code was directly inserted into the increment1 function’s body rather than being called as a separate function. The compiler likely chose to inline it because of the -O2 optimization level flag.

As a result, m_counter1 was never incremented, and m_debugAllCounters was mistakenly incremented in its place by increment1. That’s why we see 0 for m_counter1 but still see 7 for m_debugAllCounters.

In a real-world project I worked on, which involved a large codebase with numerous source files organized into multiple static libraries, we encountered a situation where some libraries were compiled without debugging options enabled for std::vector, while others were compiled with those options enabled.

It’s likely that at some point, all libraries used consistent flags. However, as the codebase grew and new libraries were added, these flags weren’t consistently applied (they weren’t default flags and had to be added manually). We were using an IDE for compilation, and determining the flags used for each library involved navigating through various tabs and windows. This was further complicated by having different (and multiple) sets of flags for different build configurations (release, debug, profile, etc.), making it even harder to notice the inconsistency.

This discrepancy led to crashes in situations where an object file compiled with one set of flags passed a std::vector to another object file compiled with different flags that then performed certain operations on that vector. These crashes were particularly difficult to debug because they only manifested in release builds, not in debug builds (or at least not in the same reproducible manner).

The debugger also behaved erratically because it was trying to debug highly optimized code. To add to the confusion, the crashes were occurring in seemingly correct and straightforward code.

The Compiler Does a Lot More Than You May Think

Throughout this article, we’ve explored some of the fundamental language constructs of C++ and how the compiler interacts with them, from the initial preprocessing stage to the final linking stage. Gaining a deeper understanding of these processes can provide valuable insights into the often-overlooked aspects of C++ development.

From its multi-stage compilation process to the intricacies of function name mangling and generating different function signatures based on context, the C++ compiler diligently works behind the scenes to unlock the power and flexibility of C++ as a compiled programming language.

I hope you find the knowledge gained from this article beneficial in your own C++ endeavors.

1 “Counters.hpp”

1 “”

1 “”

1 “/usr/include/stdc-predef.h” 1 3 4

1 “” 2

1 “Counters.hpp”

class Counters { public: Counters() : m_debugAllCounters(0), m_counter1(0), m_counter2(0) { } void inc1() { ++m_debugAllCounters; ++m_counter1; } void inc2() { ++m_debugAllCounters; ++m_counter2; } int getDebugAllCounters() { return m_debugAllCounters; } int get1() const { return m_counter1; } int get2() const { return m_counter2; } private: int m_debugAllCounters; int m_counter1; int m_counter2; };

| |

// increment1.hpp: // Forward declaration so I don’t have to include the entire header here class Counters;

int increment1(Counters&);

// increment1.cpp: #include “Counters.hpp”

void increment1(Counters& c) { c.inc1(); }

| |

| |

And a Makefile to customize the compiler flags specifically for increment2.cpp:

| |

Let’s compile everything in debug mode, without defining NDEBUG:

| |

Now, run the executable:

| |

The output aligns with our expectations. Now, let’s compile just one of the files, increment2.cpp, with NDEBUG defined (simulating a release build) and observe what happens:

| |

The output is unexpected. The increment1 function encountered a release version of the Counters class, which only has two int member fields. It incremented the first field, assuming it was m_counter1, and didn’t touch anything else because it’s unaware of the m_debugAllCounters field. I say increment1 incremented the counter because the inc1 method in Counter is marked as inline, so its code was directly inserted into the increment1 function’s body rather than being called as a separate function. The compiler likely chose to inline it because of the -O2 optimization level flag.

As a result, m_counter1 was never incremented, and m_debugAllCounters was mistakenly incremented in its place by increment1. That’s why we see 0 for m_counter1 but still see 7 for m_debugAllCounters.

In a real-world project I worked on, which involved a large codebase with numerous source files organized into multiple static libraries, we encountered a situation where some libraries were compiled without debugging options enabled for std::vector, while others were compiled with those options enabled.

It’s likely that at some point, all libraries used consistent flags. However, as the codebase grew and new libraries were added, these flags weren’t consistently applied (they weren’t default flags and had to be added manually). We were using an IDE for compilation, and determining the flags used for each library involved navigating through various tabs and windows. This was further complicated by having different (and multiple) sets of flags for different build configurations (release, debug, profile, etc.), making it even harder to notice the inconsistency.

This discrepancy led to crashes in situations where an object file compiled with one set of flags passed a std::vector to another object file compiled with different flags that then performed certain operations on that vector. These crashes were particularly difficult to debug because they only manifested in release builds, not in debug builds (or at least not in the same reproducible manner).

The debugger also behaved erratically because it was trying to debug highly optimized code. To add to the confusion, the crashes were occurring in seemingly correct and straightforward code.

The Compiler Does a Lot More Than You May Think

Throughout this article, we’ve explored some of the fundamental language constructs of C++ and how the compiler interacts with them, from the initial preprocessing stage to the final linking stage. Gaining a deeper understanding of these processes can provide valuable insights into the often-overlooked aspects of C++ development.

From its multi-stage compilation process to the intricacies of function name mangling and generating different function signatures based on context, the C++ compiler diligently works behind the scenes to unlock the power and flexibility of C++ as a compiled programming language.

I hope you find the knowledge gained from this article beneficial in your own C++ endeavors.