Working with video and its various components can be quite challenging for developers. A strong understanding of data structures, encoding methods, and image and signal processing is crucial for even seemingly straightforward video tasks like compression or editing.

To effectively handle video content, developers need to understand the properties and differences between common video file formats (like .mp4, .mov, .wmv, and .avi) and their corresponding codecs (such as H.264, H.265, VP8, and VP9). The tools needed for efficient video processing are often scattered and not readily available as comprehensive libraries, requiring developers to navigate the vast and complex world of open-source tools to create compelling computer vision applications.

Understanding Computer Vision Applications

Computer vision applications rely on a range of techniques, from basic heuristics to intricate neural networks, to analyze images or videos and generate meaningful output. Here are a few examples:

- Facial recognition: Used in smartphone cameras for organizing photos, searching albums, and tagging people on social media.

- Road marking detection: Crucial for self-driving cars to navigate safely at high speeds.

- Optical character recognition: Enables apps like Google Lens to identify text characters in images, facilitating visual search.

These diverse examples, each with a distinct function, share a common factor: they rely on images as primary input. Each application transforms unstructured, often complex, images or video frames into organized and meaningful data for end-users.

The Challenge of Video Size

While users see a video as a single entity, developers must treat it as a sequence of individual frames. For instance, detecting traffic patterns in a video requires extracting individual frames and applying algorithms to identify vehicles.

Raw video files are massive, making them difficult to store, share, and process. A minute of uncompressed 60fps video can exceed 22 gigabytes:

60 seconds * 1080 px (height) * 1920 px (width) * 3 bytes per pixel * 60 fps = 22.39 GB

Therefore, compression is essential. However, compressed video frames may not represent the entire image due to compression parameters affecting quality and detail. While the compressed video might provide an excellent viewing experience, individual frames might not be suitable for processing as complete images.

This tutorial will explore common open-source computer vision tools to address basic video processing challenges, equipping you to customize pipelines for specific needs. Audio components of video will not be covered for simplicity.

Tutorial: Building a Brightness Calculation App

A typical computer vision pipeline includes:

Step 1: Image acquisition | Images or videos can be acquired from a wide range of sources, including cameras or sensors, digital videos saved on disk, or videos streamed over the internet. |

Step 2: Image preprocessing | The developer chooses preprocessing operations, such as denoising, resizing, or conversion into a more accessible format. These are intended to make the images easier to work with or analyze. |

Step 3: Feature extraction | In the representation or extraction step, information in the preprocessed images or frames is captured. This information may consist of edges, corners, or shapes, for instance. |

Step 4: Interpretation, analysis, or output | In the final step we accomplish the task at hand. |

Let’s create a tool to calculate the average brightness of individual video frames. Our project’s pipeline will follow the model outlined above.

This tutorial’s program is available as an example within Hypetrigger, within Hypetrigger, an open-source Rust library I developed. Hypetrigger provides tools for running computer vision pipelines on streaming video, including: TensorFlow for image recognition, Tesseract for optical character recognition, and support for GPU-accelerated video decoding (10x speed boost). Install it by cloning the Hypetrigger repo and running cargo add hypetrigger.

For a comprehensive learning experience, we’ll build the pipeline from scratch instead of using Hypetrigger directly.

Our Technology Stack

We’ll be using:

Tool | Description |

|---|---|

Touted as one of the best tools out there for working with video, FFmpeg—the Swiss Army knife of video—is an open-source library written in C and used for encoding, decoding, conversion, and streaming. It is used in enterprise software like Google Chrome, VLC Media Player, and Open Broadcast Software (OBS), among others. FFmpeg is available for download as an executable command-line tool or a source code library, and can be used with any language that can spawn child processes. | |

A major strength of Rust is its ability to detect memory errors (e.g., null pointers, segfaults, dangling references) at compile time. Rust offers high performance with guaranteed memory safety, and is also highly performant, making it a good choice for video processing. |

Step 1: Image Acquisition

We’ll assume a animated sample video is available for processing.

Step 2: Image Preprocessing

This step involves converting the H.264 encoded video to raw RGB format, which is easier to work with.

We’ll use FFmpeg’s command-line tool within a Rust program to decompress and convert our sample video to RGB. For optimal results, specific FFmpeg syntax will be added to the ffmpeg command:

Argument* | Description | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

-i | Indicates the file name or URL of the source video. | The URL of the sample video or another of your choosing |

-f | Sets the output format. | The rawvideo format to obtain raw video frames |

-pix_fmt | Sets the pixel format. | rgb24 to produce RGB color channels with eight bits per channel |

-r | Sets the output frame rate. | 1 to produce one frame per second |

<output> | Tells FFmpeg where to send output; it is a required final argument. | The identifier pipe:1 to output on standard output instead of to file |

*For a complete list of arguments, use ffmpeg -help.

The command ffmpeg -i input_video.mp4 -f rawvideo -pix_fmt rgb24 pipe:1 allows us to process the video frames:

| |

Our program will process one decoded RGB frame at a time. To manage memory, we’ll allocate a frame-sized buffer, releasing memory after processing:

| |

The while loop accesses raw_rgb, containing a full RGB image.

Step 3: Feature Extraction

To calculate average frame brightness, we’ll add this function (before or after the main method):

| |

At the end of the while loop, we calculate and print brightness:

| |

The code now resembles this example file.

Running this program with our sample video will output:

| |

Step 4: Interpretation

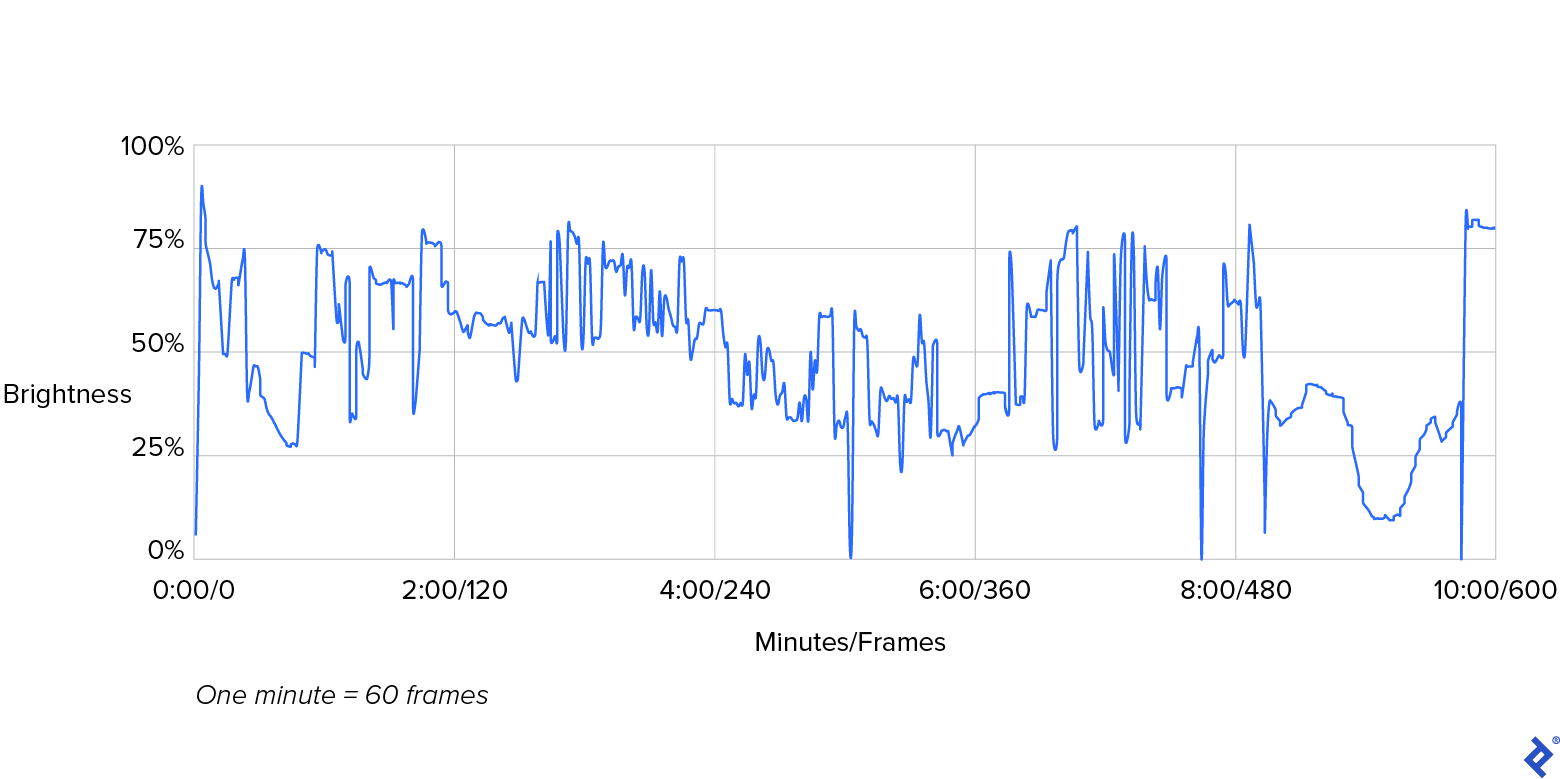

Here’s a graph representing the output:

The graph depicts the video’s brightness level, with peaks and valleys representing transitions between frames. The initial brightness at frame 0 is 5% (dark), peaking at 87% (bright) just two frames later. Significant transitions occur around 5:00, 8:00, and 9:40, representing typical movie scene changes.

Real-World Applications

In practical applications, brightness analysis can trigger actions. In post-production, editors could use this data to select frames within a specific brightness range or review those outside the range.

Another application is analyzing security footage. By comparing brightness levels with entry/exit logs, we could identify if lights are left on after hours and send energy-saving reminders.

This tutorial covers basic video processing and sets the stage for advanced techniques like analyzing multiple features and correlations using advanced statistical measures. Such analysis bridges video processing with statistical inference and machine learning, forming the core of computer vision.

By following these steps and utilizing the provided tools, you can overcome challenges associated with video decompression and RGB pixel interpretation. This simplification allows you to focus on developing intelligent and robust video capabilities for your applications.

Special thanks to Martin Goldberg from the Toptal Engineering Blog editorial team for reviewing the code samples and technical content.