In the realm of Java development, a common practice involves restarting the server whenever a class is modified, and this has become an accepted norm. This is an undeniable aspect of Java development, a routine we’ve adhered to from our initial encounter with the language. However, does reloading Java classes have to be such a hurdle? Could tackling this challenge present a stimulating endeavor for proficient Java developers? Within the scope of this Java class tutorial, I’ll endeavor to address this very issue, guiding you towards harnessing the full potential of real-time class reloading and significantly amplifying your productivity.

Discussions surrounding Java class reloading are infrequent, and the available documentation delving into this process is scarce. My aim here is to change that. This tutorial will provide a meticulous, step-by-step breakdown of this process, empowering you to master this remarkable technique. Bear in mind that implementing Java class reloading demands a high degree of diligence, but acquiring this skill will elevate your standing as both a Java developer and a software architect. Additionally, it wouldn’t hurt to familiarize yourself with how to circumvent the 10 most prevalent Java pitfalls.

Establishing Your Workspace

The complete source code accompanying this tutorial is available on GitHub here.

To execute the code as you progress through this tutorial, you’ll require Maven, Git, and either Eclipse or IntelliJ IDEA.

For Eclipse Users:

- Execute the command

mvn eclipse:eclipseto generate project files compatible with Eclipse. - Proceed to load the generated project.

- Configure the output path to

target/classes.

For IntelliJ Users:

- Import the project’s

pomfile. - IntelliJ won’t automatically compile your code while running examples. You can address this by either:

- Running the examples within IntelliJ and manually compiling using

Alt+B Ewhenever needed. - Running the examples externally using the provided

run_example*.batscripts while enabling IntelliJ’s auto-compile feature for automatic compilation upon saving changes to Java files.

Illustration 1: Reloading a Class Using Java ClassLoader

This initial example will provide you with a fundamental grasp of the Java class loader. Here is the source code.

Consider the following definition of the User class:

| |

We can perform the following actions:

| |

Within this tutorial example, two instances of the User class will reside in memory. userClass1 will be loaded by the JVM’s default class loader, while userClass2 will be loaded using DynamicClassLoader—a custom class loader whose source code is also included in the GitHub repository and which I will elaborate on shortly.

The remaining portion of the main method is as follows:

| |

And the output it produces:

| |

As demonstrated, despite sharing the same name, these User classes are distinct entities. They can be managed and manipulated independently. The age value, declared as static, exists in two separate instances, each associated with its corresponding class, and can be modified independently as well.

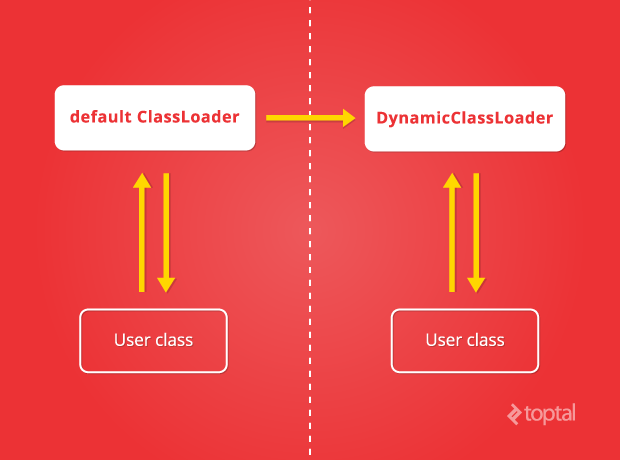

In a typical Java program, the ClassLoader acts as a gateway, ushering classes into the JVM. When a class requires another class to be loaded, it becomes the responsibility of the ClassLoader to handle this task.

However, in this particular Java class example, the custom ClassLoader named DynamicClassLoader is employed to load the second iteration of the User class. Had we opted to use the default class loader again (by invoking StaticInt.class.getClassLoader()), the same User class would be utilized since all loaded classes are cached.

Demystifying DynamicClassLoader

Within a standard Java program, multiple class loaders can coexist. The one responsible for loading your main class is designated as the default class loader, and you are at liberty to create and utilize as many additional class loaders as you see fit. This, in essence, forms the crux of class reloading in Java. Given that the DynamicClassLoader constitutes arguably the most pivotal element of this entire tutorial, it’s essential to grasp the mechanics of dynamic class loading before we can attain our objective.

In contrast to the conventional behavior of a ClassLoader, our DynamicClassLoader adopts a more proactive strategy. A typical class loader would prioritize its parent ClassLoader, only taking on the responsibility of loading classes that its parent is unable to handle. While this approach proves suitable under normal circumstances, it doesn’t align with our current requirements. Instead, the DynamicClassLoader will diligently attempt to search through all its designated class paths and resolve the target class before relinquishing control to its parent.

In the example we’ve been examining, the DynamicClassLoader is initialized with a solitary class path: "target/classes" (representing our current directory). This empowers it to load all classes residing in that specific location. For any classes outside this designated path, it would need to defer to its parent class loader. For instance, if our StaticInt class necessitates the loading of the String class, and our class loader lacks access to the rt.jar file within our JRE directory, the String class associated with the parent class loader will be utilized.

The subsequent code snippet is extracted from AggressiveClassLoader, the parent class of DynamicClassLoader, and it elucidates where this specific behavior is defined.

| |

Pay close attention to the following attributes of DynamicClassLoader:

- The classes loaded by

DynamicClassLoaderexhibit the same performance characteristics and possess other attributes identical to those of classes loaded by the default class loader. - The

DynamicClassLoader, along with all the classes and objects it has loaded, becomes eligible for garbage collection.

Equipped with the capability to load and operate with two versions of the same class, our next logical step is to explore the possibility of discarding the outdated version and substituting it with a freshly loaded one. In the subsequent example, we’ll delve into precisely that—and we’ll do so repeatedly.

Illustration 2: Continuous Class Reloading

This Java example will showcase the JRE’s ability to perpetually load and reload classes, seamlessly discarding outdated classes for garbage collection while loading and utilizing brand new class definitions from the hard drive. Here is the source code.

Let’s examine the main loop:

| |

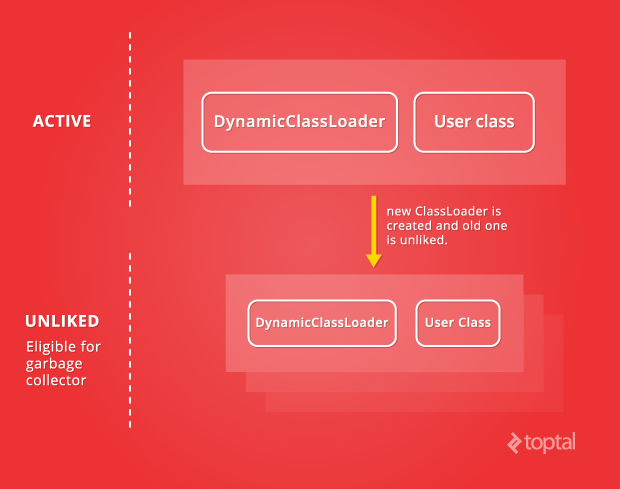

Every two seconds, the existing User class will be discarded, and a new one will be loaded, followed by the invocation of its hobby method.

Below is the definition of the User class:

| |

As you execute this application, experiment with commenting and uncommenting the designated code within the User class. You’ll observe that the most recent definition consistently takes precedence.

Here’s a sample output:

| |

With each new instance of DynamicClassLoader created, it will proceed to load the User class from the target/classes folder—the designated output directory for our compiled class files in both Eclipse and IntelliJ. All previous instances of DynamicClassLoader and outdated User classes will be disassociated and become eligible for garbage collection.

For those acquainted with JVM HotSpot, it’s worth noting that even the structure of a class can be modified and reloaded. In our example, we could remove the playFootball method and introduce a playBasketball method. This sets it apart from HotSpot, which only permits changes within the content of methods; modifying the class structure in HotSpot would prevent class reloading.

Now that we’ve established the ability to reload a single class, let’s attempt to reload multiple classes concurrently. Our next example will demonstrate this.

Illustration 3: Reloading Multiple Classes

The output of this example will mirror that of Example 2. However, it will illustrate how to implement this behavior within a structure more akin to a real-world application, incorporating context, service, and model objects. Due to its size, I’ll only present excerpts of this example’s source code here. The complete source code can be found here.

Let’s begin with the main method:

| |

Followed by the createContext method:

| |

Next, the invokeHobbyService method:

| |

Now, the Context class:

| |

And the HobbyService class:

| |

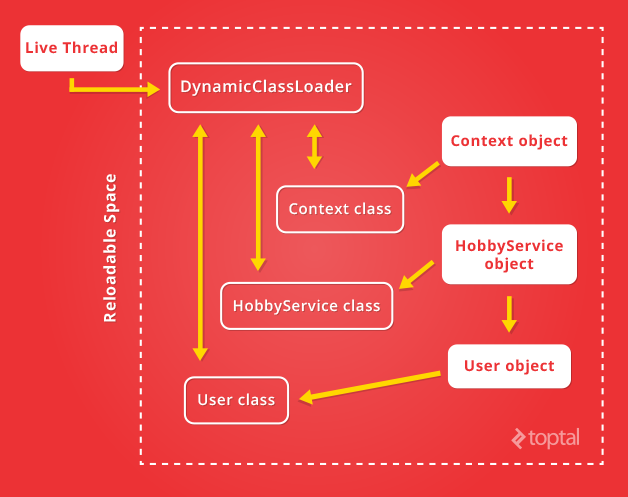

The Context class in this example exhibits greater complexity compared to the User class from our previous examples. It maintains links to other classes and includes an init method that gets invoked upon each instantiation. In essence, it closely resembles the context classes found in real-world applications, which are responsible for managing an application’s modules and handling dependency injection. Consequently, the ability to reload this Context class along with all its interconnected classes represents a significant stride toward practically applying this technique in real-world scenarios.

As the number of classes and objects involved increases, the task of “dropping” outdated versions becomes more intricate. This complexity lies at the heart of why class reloading can be quite challenging. To effectively discard old versions, we need to ensure that once the new context is established, all references to the outdated classes and objects are severed. So, how do we tackle this gracefully?

In our current setup, the main method maintains a reference to the context object, and this reference serves as the sole link to everything we intend to discard. By breaking this link—effectively releasing the context object, its corresponding class, the service object, and so on—we render them all eligible for garbage collection.

Allow me to elaborate on why classes typically exhibit persistence and tend to evade garbage collection:

- In a standard scenario, we load all our classes into the default Java class loader.

- The relationship between a class and its class loader is bidirectional, with the class loader maintaining a cache of all the classes it has loaded.

- As long as a class loader remains connected to any active thread, everything it has loaded (all its classes) remains shielded from the garbage collector.

- Therefore, unless we can effectively isolate the code we aim to reload from the code already loaded by the default class loader, any changes we introduce to our code will not be applied during runtime.

This example demonstrates that reloading all of an application’s classes can be surprisingly straightforward. The key objective is to maintain a thin, easily severable connection from the active thread to the dynamic class loader currently in use. But what if our goal is to prevent certain objects (and their associated classes) from being reloaded, allowing them to be reused across reloading cycles? Let’s explore this in the next example.

Illustration 4: Decoupling Persisted and Reloaded Class Spaces

Here’s the main method:

| |

The strategy here involves loading the ConnectionPool class and instantiating it outside the reloading cycle. This confines it to the persistent space, and we then pass its reference to the Context objects.

The createContext method also undergoes a slight modification:

| |

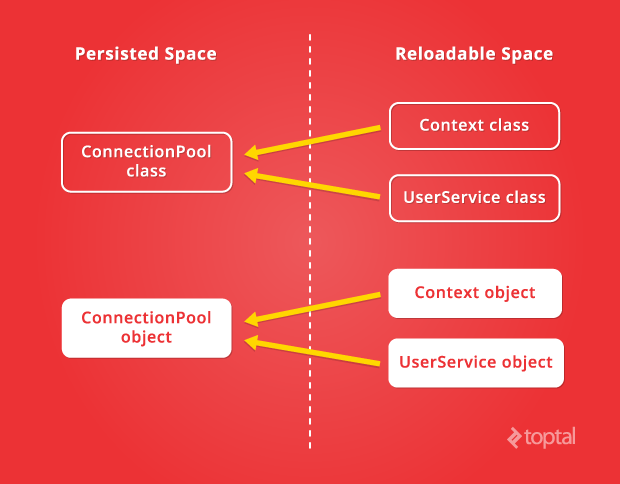

Moving forward, we’ll refer to the objects and classes that undergo reloading with each cycle as residing in the “reloadable space,” while those that remain unchanged and persist across reloading cycles will be classified as belonging to the “persisted space.” Maintaining clarity regarding which objects and classes reside in which space is crucial, effectively drawing a clear boundary between these two domains.

As depicted in the diagram, not only do the Context and UserService objects reference the ConnectionPool object, but the Context and UserService classes also hold references to the ConnectionPool class. This presents a potentially hazardous situation that often gives rise to confusion and errors. It is imperative that the ConnectionPool class is not loaded by our DynamicClassLoader; there should exist only one instance of the ConnectionPool class in memory, specifically the one loaded by the default ClassLoader. This exemplifies why meticulous care is paramount when architecting a class-reloading mechanism in Java.

Consider the implications if our DynamicClassLoader were to inadvertently load the ConnectionPool class. The ConnectionPool object residing in the persistent space would become incompatible with the Context object. This is because the Context object anticipates an object belonging to a different class, one that also happens to be named ConnectionPool but is, in fact, distinct.

So, how do we prevent our DynamicClassLoader from loading the ConnectionPool class? Instead of directly using DynamicClassLoader, this example employs a subclass named ExceptingClassLoader. This subclass delegates the loading responsibility to its superclass (the default class loader) based on a predefined condition:

| |

Without using ExceptingClassLoader, the DynamicClassLoader would proceed to load the ConnectionPool class due to its presence in the "target/classes" folder. An alternative approach to prevent the ConnectionPool class from being picked up by our DynamicClassLoader involves compiling it to a separate directory, potentially within a different module, ensuring its independent compilation.

Establishing Space Allocation Rules

At this juncture, the task of Java class loading might appear rather convoluted. How do we determine which classes should reside in the persistent space and which belong in the reloadable space? Let’s establish some guiding principles:

- Classes within the reloadable space are permitted to reference classes in the persisted space. However, the reverse is strictly prohibited; classes in the persisted space must not contain references to classes in the reloadable space. In our previous example, the reloadable

Contextclass references the persistentConnectionPoolclass, but theConnectionPoolclass remains entirely oblivious to the existence ofContext. - A class has the flexibility to exist in either space provided it refrains from referencing any classes in the opposing space. For instance, a utility class composed entirely of static methods, such as

StringUtils, can be loaded once into the persistent space and loaded separately within the reloadable space.

These rules, as you can see, are not overly restrictive. With the exception of classes that bridge the two spaces due to cross-references, all other classes enjoy the freedom to reside in either the persisted space, the reloadable space, or even both. It’s important to note that only classes within the reloadable space benefit from the dynamic reloading mechanism.

With this, we’ve addressed the most formidable challenge associated with class reloading. In our final example, we’ll endeavor to apply this technique to a simplified web application, experiencing the convenience of on-the-fly Java class reloading, much like working with a scripting language.

Illustration 5: A Miniature Phone Book Application

This example will bear a strong resemblance to the structure of a typical web application. It takes the form of a Single Page Application built using AngularJS, SQLite, Maven, and Jetty Embedded Web Server.

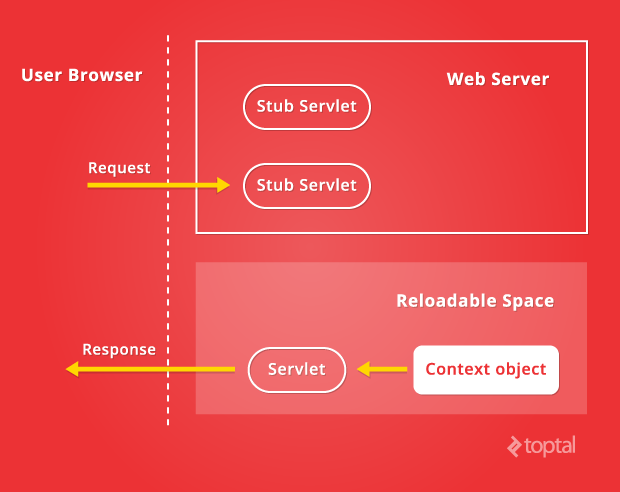

Let’s visualize the reloadable space within the web server’s architecture:

The web server will refrain from holding direct references to the actual servlets, as these need to remain within the reloadable space to facilitate reloading. Instead, it will maintain references to stub servlets. These stubs, whenever their service method is invoked, will dynamically resolve the actual servlet within the appropriate context to handle the request.

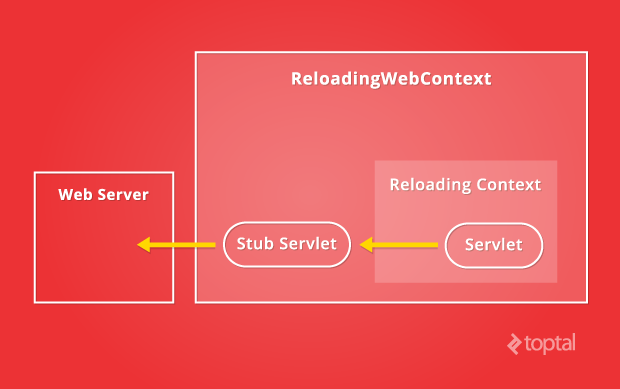

This example introduces a new element called ReloadingWebContext. This object provides the web server with all the necessary values akin to a regular context object. However, internally, it manages references to an actual context object that our DynamicClassLoader can reload. The ReloadingWebContext acts as the provider of stub servlets to the web server.

The ReloadingWebContext will essentially wrap the actual context and handle the following:

- Reload the actual context whenever an HTTP GET request is made to “/”.

- Supply stub servlets to the web server.

- Set values and invoke methods whenever the actual context undergoes initialization or destruction.

- Offer configuration options to enable or disable context reloading and specify the class loader to be used for reloading. This proves beneficial when deploying the application in a production environment.

Given the critical importance of understanding how we maintain separation between the persisted and reloadable spaces, let’s examine the two classes that straddle this boundary:

Class qj.util.funct.F0 for the public F0<Connection> connF object within the Context class

- This represents a function object, responsible for returning a

Connectioninstance each time it’s invoked. The class resides within theqj.utilpackage, which is explicitly excluded from theDynamicClassLoader’s purview.

Class java.sql.Connection for the public F0<Connection> connF object within the Context class

- This is the standard SQL connection object. Since it falls outside the class path managed by our

DynamicClassLoader, it won’t be inadvertently loaded.

In Conclusion

Throughout this Java classes tutorial, we’ve explored how to reload individual classes, reload single classes continuously, reload an entire collection of classes, and even reload groups of classes while maintaining the persistence of others. Armed with these techniques, the paramount factor in achieving robust class reloading lies in establishing a meticulously clean design. With this foundation in place, you gain remarkable flexibility in manipulating your classes and harnessing the full power of the JVM.

Implementing Java class reloading might not be the most straightforward endeavor. However, if you choose to embark on this journey and reach a point where your classes seamlessly reload on the fly, you’ll be well on your way. From there, it’s a short but rewarding leap to achieving an impeccably clean and powerful architecture for your system.

Best of luck, my fellow developers, and may you relish this newfound mastery!