As a user, you don’t think about the inner workings of your software. You just need it to function seamlessly, securely, and without any hiccups. Developers understand this need and work diligently to meet your expectations. One challenge they tackle is ensuring the software’s data storage aligns perfectly with the current version. Software is always evolving, and naturally, its data model might need adjustments along the way, perhaps to rectify initial design flaws. To make things even more intriguing, consider the scenarios of testing environments or customers transitioning to updated software versions at varying speeds. Documenting the storage structure and the necessary steps to utilize the latest version from a single viewpoint simply isn’t sufficient.

I vividly recall joining a project that had several databases, each with structures altered on-the-fly, directly by the developers. The lack of a systematic approach meant there was no clear method to determine the modifications needed to update the structure to the latest version. Version control? It was nonexistent! This was before the DevOps era, and such practices would be deemed utterly chaotic today. Our solution? We crafted a tool designed to apply each alteration to a designated database. This tool incorporated migrations and meticulously documented schema changes. It instilled confidence, guaranteeing that changes were intentional and the schema state remained predictable.

This article delves into the realm of relational database schema migrations and tackles the hurdles encountered along the way.

But first, let’s define “database migrations.” In our current context, a migration represents a collection of changes applied to a database. Common examples include adding or removing tables, columns, or indexes. The overall structure of your schema can transform significantly over time, particularly if development began with ambiguous requirements. As you progress through various project milestones toward a release, your data model will have undergone an evolution, potentially becoming vastly different from its initial form. Migrations are essentially the stepping stones guiding you to your desired schema state.

Instead of reinventing the wheel, let’s first explore the existing tools that can streamline this process.

Available Tools

Numerous libraries are available for widely used programming languages that simplify database migrations. Take Java, for instance, where popular choices include Liquibase and Flyway. While we’ll primarily illustrate concepts using Liquibase, it’s important to note that these principles are transferable to other solutions and are not specific to Liquibase.

You might wonder, why use a separate library for schema migration when Object-Relational Mapping (ORM) tools often provide automatic schema upgrades to match the mapped class structure? While convenient, automatic migrations typically handle only basic schema adjustments like creating tables or columns. They often stumble when dealing with potentially irreversible actions like deleting or renaming database objects. This limitation is why non-automatic (though still automated) solutions are generally favored. They compel you to explicitly define the migration logic, giving you complete control and predictability over the changes applied to your database.

Combining automated and manual schema modifications is strongly discouraged. It creates a recipe for unpredictable and unique schemas, especially if manual changes are applied in the incorrect sequence or inconsistently. Once you’ve chosen your tool, stick with it for all schema migrations.

Common Database Migrations

Typical migrations involve tasks like generating sequences, tables, columns, primary and foreign keys, indexes, and other database elements. For most common alterations, Liquibase offers dedicated declarative elements to clearly outline the intended actions. While detailing every minute change supported by Liquibase or similar tools would be tedious, let’s examine an example of table creation to illustrate how these changesets are structured (XML namespace declarations are omitted for brevity):

| |

The changelog, as you can see, comprises multiple changesets, and each changeset encompasses one or more changes. These simple changes, like ‘createTable,’ can be combined to achieve more complex migrations. For instance, imagine needing to update the product codes for all existing products. This could be accomplished with the following change:

| |

However, this approach might lead to performance bottlenecks if you’re dealing with a massive number of products. To expedite this migration, we can break it down into these optimized steps:

- Employ the

createTablechange to generate a new table for products, similar to the previous example. In this initial phase, it’s best to minimize the number of constraints. We can name this new tablePRODUCT_TMP. - Populate

PRODUCT_TMPusing an SQLINSERT INTO ... SELECT ...statement within asqlchange. - Introduce all the required constraints (

addNotNullConstraint,addUniqueConstraint,addForeignKeyConstraint) and indexes (createIndex). - Rename the existing

PRODUCTtable to something likePRODUCT_BAK, achievable with Liquibase’srenameTablefunction. - Use

renameTableagain to renamePRODUCT_TMPtoPRODUCT. - Optionally, remove the

PRODUCT_BAKtable usingdropTable.

While it’s generally advisable to avoid such extensive migrations, it’s beneficial to understand their implementation should you encounter a rare scenario where they become necessary.

If using XML, JSON, or YAML feels awkward for defining changes, then use plain SQL and leverage all the database-specific features available. Additionally, you have the flexibility to implement any custom logic using plain Java.

While Liquibase’s abstraction from writing specific SQL can be liberating, it’s crucial to remain aware of your target database’s quirks. For example, when creating foreign keys, the automatic creation of indexes might differ based on the specific database management system in use. This variation could lead to unexpected outcomes. Fortunately, Liquibase allows you to designate changesets to run only on particular database types like PostgreSQL, Oracle, or MySQL. This feature facilitates the reuse of vendor-agnostic changesets across different databases, while still allowing for vendor-specific syntax and features where needed. The following changeset, for example, will only execute on an Oracle database:

| |

Beyond Oracle, Liquibase natively supports several other other databases.

Database Object Naming

Each database object you create requires a name. While some, like constraints and indexes, don’t demand explicit names, the database will assign them automatically. This auto-naming becomes problematic when you need to reference those objects later for deletion or modification. Assigning explicit names from the outset is always recommended.

The question then arises, what are the rules for naming these objects? The simple answer: Be consistent. For instance, if you adopt the convention of naming indexes as IDX_<table>_<columns>, then an index for the CODE column mentioned earlier should be named IDX_PRODUCT_CODE.

Naming conventions are often a subject of passionate debate, so we won’t attempt to provide exhaustive guidelines here. Strive for consistency, adhere to your team’s or project’s established conventions, or if none exist, establish your own!

Structuring Changesets

A crucial initial decision is where to house your changesets. Two primary approaches exist:

- Store changesets alongside the application code. This method is convenient for committing and reviewing changesets in conjunction with application code.

- Maintain changesets and application code separately, perhaps in distinct VCS repositories. This strategy is beneficial when a data model is shared across multiple applications. It centralizes changesets within a dedicated repository, preventing their dispersal across various application code repositories.

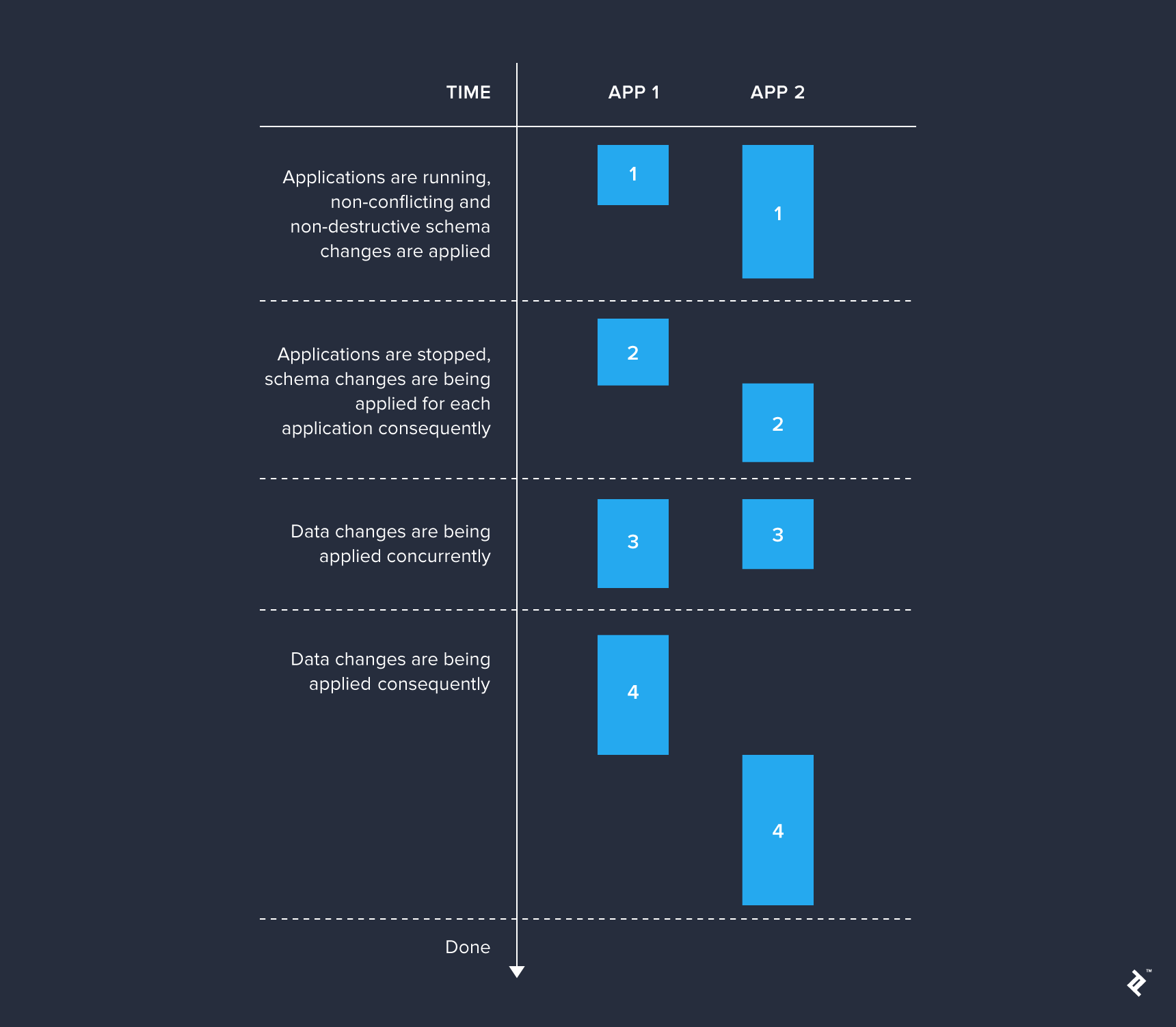

Irrespective of where you store your changesets, it’s generally wise to categorize them as follows:

- Independent migrations that don’t impact the live system. Creating new tables, sequences, etc., is usually safe if the currently deployed application doesn’t interact with them yet.

- Schema adjustments that alter the core storage structure, such as adding or removing columns and indexes. These changes should be implemented only when older application versions are offline to prevent locks or unexpected behavior arising from the altered schema.

- Quick migrations involving minimal data insertion or updates. If deploying multiple applications, changesets in this category can be executed concurrently without significantly impacting database performance.

- Potentially time-consuming migrations handling substantial data insertions or updates. These changes are best applied when other similar migrations are not running.

These migration sets should be executed sequentially before deploying a newer application version. This approach is especially useful for systems comprising several independent applications that utilize the same database. Otherwise, it’s worthwhile to separate only those changesets applicable without affecting live applications, while the rest can be applied together.

Simpler applications can apply the complete set of necessary migrations during startup. In this scenario, all changesets fall under a single category and are executed whenever the application initializes.

Regardless of the chosen migration application stage, it’s crucial to acknowledge that sharing the same database across multiple applications can lead to locks during migration execution. Liquibase, like many comparable tools, uses two special tables for storing its metadata: DATABASECHANGELOG and DATABASECHANGELOGLOCK. The former logs applied changesets, while the latter prevents simultaneous migrations within the same database schema. Therefore, if multiple applications must use the same database schema, it’s wise to customize the names of these metadata tables to avoid potential lock conflicts.

With the high-level structure clarified, let’s now focus on organizing changesets within each category.

While the specifics depend on your application’s needs, the following practices are generally beneficial:

- Organize changelogs based on your product releases. Create a dedicated directory for each release, placing the corresponding changelog files within. Maintain a root changelog and utilize include changelogs that correspond to specific releases. Within each release changelog, include other changelogs that are part of that release.

- Establish and consistently adhere to a naming convention for both changelog files and changeset identifiers.

- Avoid excessively large changesets. Favor multiple smaller changesets over a single monolithic one.

- If using stored procedures that require updates, consider using the

runOnChange="true"attribute within the changeset where the stored procedure is initially added. This approach avoids creating a new changeset for every procedure update, which is often acceptable as tracking such granular history might not always be necessary. - Before merging feature branches, consider condensing redundant changes. It’s common in feature branches, particularly long-lived ones, to have later changesets refine earlier ones. For example, you might create a table and later decide to add more columns. If the feature branch hasn’t been merged, it’s cleaner to include those additional columns within the initial

createTablechange. - Utilize the same changelogs for test database creation. Applying this practice might reveal changesets inapplicable to the test environment or necessitate additional test-specific changesets. Liquibase simplifies this by using contexts. Add the

context="test"attribute to changesets meant for test execution and initialize Liquibase with thetestcontext enabled.

Rollback Strategies

Liquibase, similar to its counterparts, enables schema migrations both “up” and “down.” However, be aware that undoing migrations can be intricate and might not always be worthwhile. If you opt to support rollback functionality in your application, ensure consistency by implementing it for every changeset that might need reversal. In Liquibase, rolling back a changeset involves adding a rollback tag containing the changes necessary for the undo operation. Consider this example:

| |

In this case, an explicit rollback is unnecessary because Liquibase would automatically perform the same rollback actions. Liquibase can inherently reverse most supported change types, such as createTable, addColumn, or createIndex.

Rectifying Past Mistakes

Everyone makes mistakes, and sometimes, these errors are discovered only after flawed changes have been implemented. Let’s explore ways to salvage such situations.

Manual Database Updates

This method involves directly modifying the DATABASECHANGELOG table and your database using these steps:

- To correct erroneous changesets and re-execute them:

- Remove the rows from

DATABASECHANGELOGassociated with the problematic changesets. - Revert any side effects introduced by these changesets. For example, if a table was dropped, restore it.

- Rectify the faulty changesets.

- Re-run the migrations.

- Remove the rows from

- To correct erroneous changesets without reapplying them:

- Update the

DATABASECHANGELOGtable by setting theMD5SUMfield toNULLfor rows corresponding to the faulty changesets. - Manually fix the database inconsistencies. For instance, if a column was added with an incorrect data type, execute a query to modify its type.

- Rectify the faulty changesets.

- Re-run the migrations. Liquibase will calculate the new checksum and store it in

MD5SUM, preventing the corrected changesets from re-executing.

- Update the

While these manual interventions are relatively straightforward during development, they become significantly more complex when changes have been applied to multiple databases.

Implementing Corrective Changesets

In practice, corrective changesets often offer a more suitable approach. You might wonder, why not directly edit the original changeset? The answer depends on the nature of the required changes. Liquibase computes a checksum for each changeset and prevents the application of new changes if the checksum differs for any previously applied changeset. This behavior, however, can be tailored on a per-changeset basis using the runOnChange="true" attribute. Modifying the preconditions or optional changeset attributes (context, runOnChange, etc.) doesn’t impact the checksum.

So, how do you effectively rectify changesets containing errors?

- If you want the corrected changes applied to new schemas, simply add corrective changesets. For instance, if a column was added with an incorrect data type, you would modify its type within a new changeset.

- If you want to essentially erase the existence of the faulty changesets, follow these steps:

- Remove the problematic changesets or add the

contextattribute with a value that guarantees they’ll never be applied again, e.g.,context="graveyard-changesets-never-run". - Introduce new changesets that either reverse or fix the incorrect actions. These changes should only execute if the faulty changes were previously applied. This conditional application can be achieved using preconditions like

changeSetExecuted. Include a comment explaining the rationale behind this corrective action. - Finally, add new changesets that modify the schema correctly.

- Remove the problematic changesets or add the

While fixing past mistakes is achievable, as you can see, it’s not always a simple process.

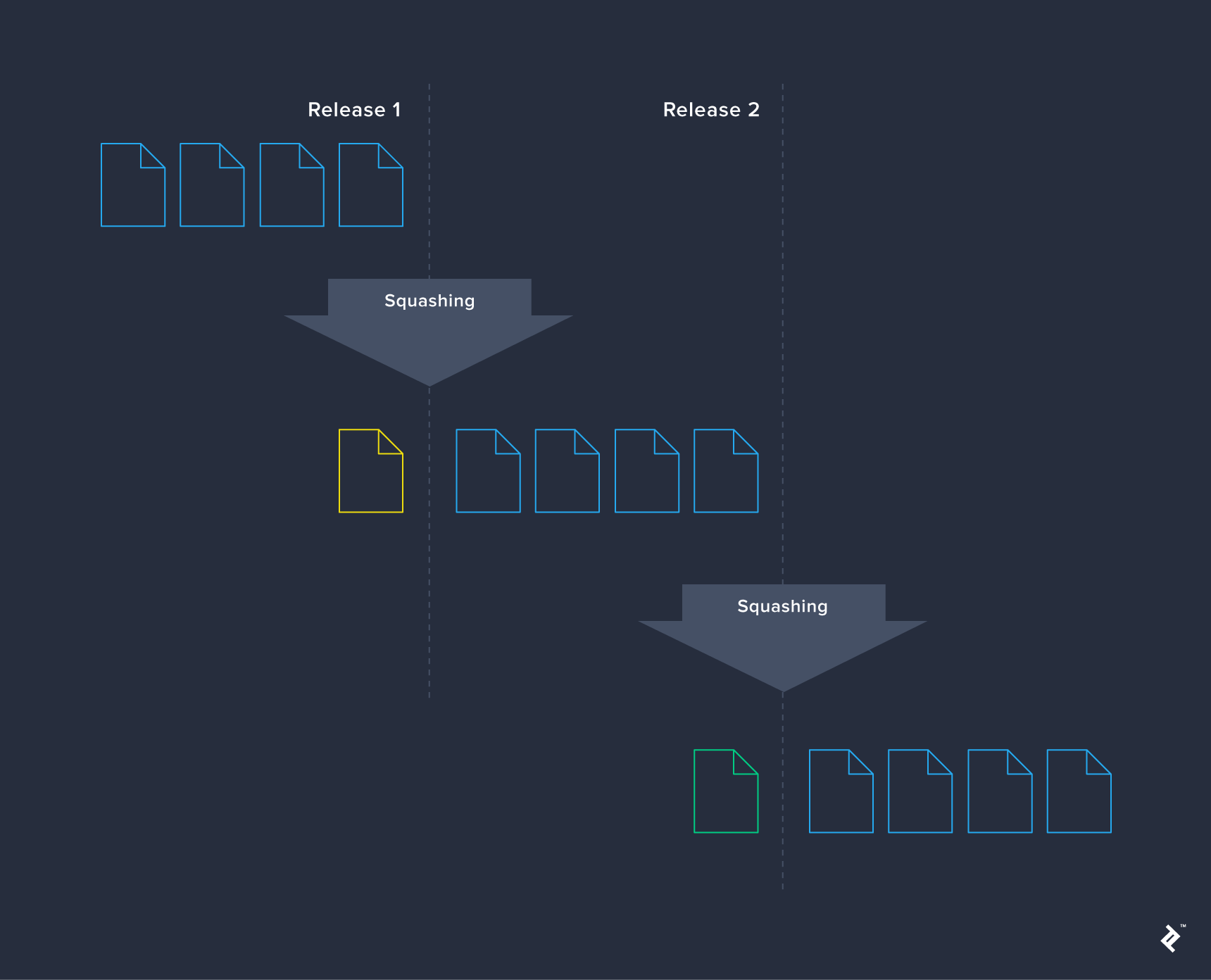

Managing Growth and Complexity

As your application matures, so does its changelog, accumulating a history of every schema modification. This accumulation is inherent to the process and isn’t inherently negative. Periodically condensing migrations, such as after each product release, can help manage lengthy changelogs. In certain cases, it can accelerate the initialization of fresh schemas.

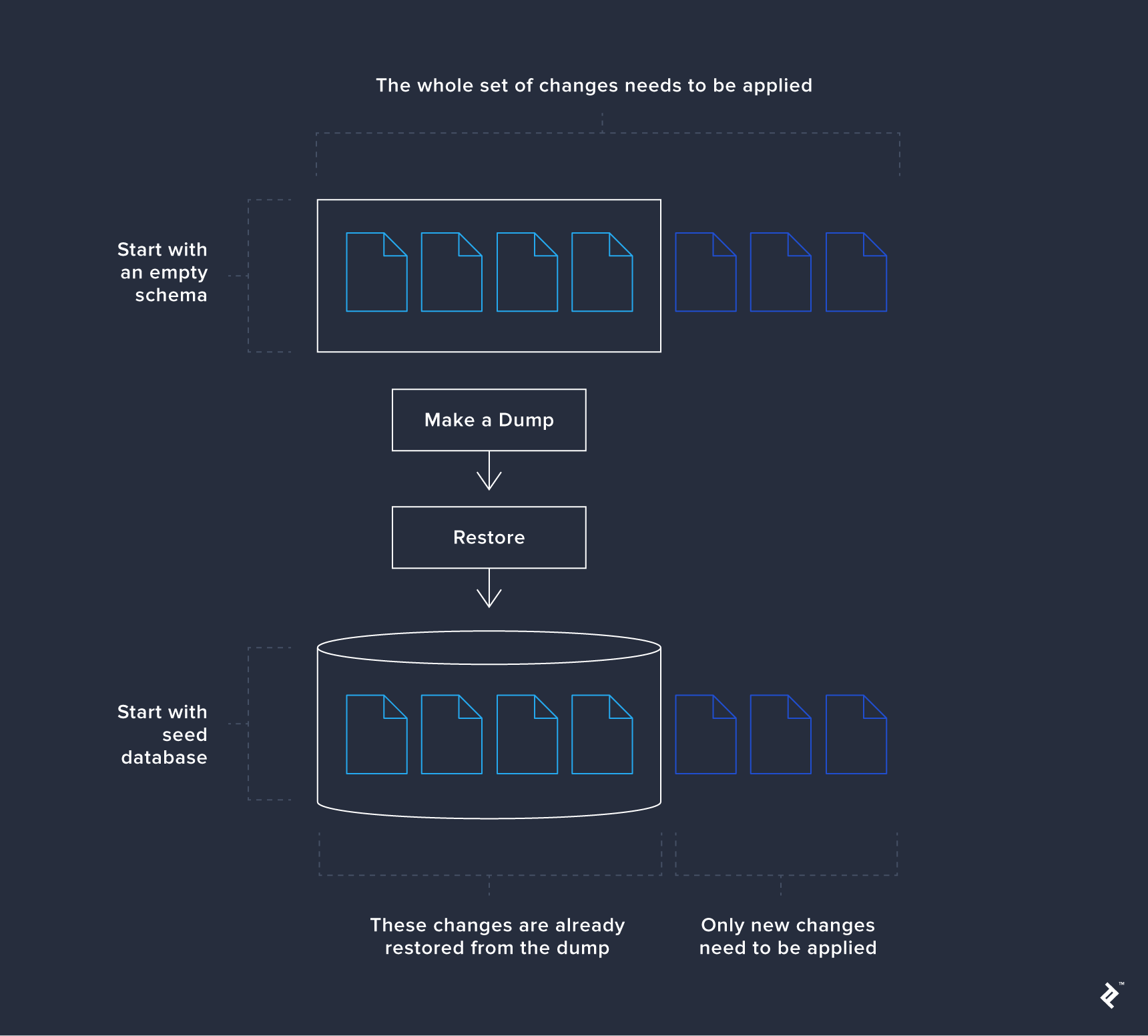

However, squashing isn’t always straightforward and may introduce regressions without significant advantages. An alternative strategy is using a seed database to bypass executing all changesets. This approach is particularly beneficial for test environments where rapid database availability, potentially pre-populated with test data, is crucial. Consider it a form of changeset squashing: you take a schema snapshot at a specific point, such as after a release. Restoring this snapshot allows you to apply migrations as usual, with only new changes being executed. Older changes, already incorporated in the snapshot, are restored directly from the dump.

Conclusion

This article intentionally avoided a deep dive into Liquibase’s extensive feature set. Our aim was to provide a concise and focused exploration of schema evolution in general. We hope to have illuminated the benefits and challenges associated with automating database schema migrations and how seamlessly this approach integrates with a DevOps culture.

Remember, even sound practices shouldn’t become rigid dogma. Each project has unique needs, and as database engineers, our choices should prioritize propelling a product forward, not blindly adhering to recommendations found online.