It’s practically a sure thing. Whether you’re just starting or you’re a seasoned pro, dealing with anything from high-level architecture to low-level assembly, focused on enhancing machine speed or developer productivity, there’s a good possibility you and your team are unintentionally hindering your own objectives.

What? Me? My team?

That’s quite a serious claim to make. Let me elaborate.

Optimization isn’t the ultimate solution, but it can be just as challenging to accomplish. I’d like to share some straightforward advice (along with a heap of potential problems) to help your team transition from a pattern of self-sabotage to one marked by collaboration, satisfaction, equilibrium, and eventually, optimization.

What Is Premature Optimization?

Premature optimization is trying to optimize performance:

- Right when you start writing an algorithm

- Before any benchmarks tell you it’s necessary

- Before profiling shows you exactly where it’s worthwhile

- At a lower level than your project currently requires

Now, I’m an optimist, Optimus.

Or at least I’m going to pretend to be while writing this. You can pretend your name is Optimus too, so this feels more directly relevant.

As tech professionals, we probably all wonder how it can be $year and yet, with all our progress, it’s somehow acceptable for $task to still be so incredibly time-consuming. We want to be streamlined. Efficient. Remarkable. Like the Rockstar Programmers those job ads are always looking for, but with leadership skills too. So when our teams code, we encourage them to do it right the first time (even though “right” is subjective here). We all know that’s the Clever Coder way, and the way of Those Who Don’t Need to Waste Time Refactoring Later.

I understand. The desire for perfection is strong in me too. We want to invest a little time now to avoid a lot of time later, because we’ve all struggled with “Shitty Code Other People Wrote (What the Hell Were They Thinking?).” That’s SCOPWWHWTT for short, because who doesn’t love an unpronounceable acronym?

We also don’t want our team’s code to become that for themselves or others down the line.

So let’s explore how to steer our teams in the right direction.

What to Optimize: Embracing the Art

When we think of program optimization, we often jump to performance. However, even that is less specific than it seems (speed? memory usage? etc.), so let’s pause there.

Let’s make it even more open-ended! At least initially.

My web-like brain craves order, so it takes every bit of optimism I have to view what I’m about to say as positive.

There’s a simple (performance) optimization rule: Don’t do it. This seems easy to follow strictly, but not everyone agrees. I don’t fully agree either. Some people naturally write better code from the start. We’d hope that, for most programmers, their code quality improves over time on new projects. But for many, this isn’t the case. The more they learn, the more they’re tempted to prematurely optimize.

For many programmers… the more they know, the more ways they will be tempted to prematurely optimize.

Therefore, this Don’t do it isn’t an exact science. It’s meant to counter the typical techie’s urge to solve the puzzle. This urge is often what draws programmers to coding. I get it. But I urge you to resist the temptation. If you need a puzzle right now, do a Sudoku, solve a Mensa puzzle, or go code golfing with a made-up problem. Leave it out of the repo until the right time. Almost always, this is wiser than pre-optimization.

This practice is so infamous that people ask if premature optimization is the root of all evil. (I wouldn’t go that far, but I understand the sentiment.)

I’m not suggesting we choose the most simplistic method at every design stage. Absolutely not. But instead of the cleverest-looking solution, we can prioritize consider other values:

- Easiest for a new hire to understand

- Most likely to pass a senior developer’s code review

- Most maintainable

- Fastest to write

- Easiest to test

- Most portable

- etc.

Here’s where the issue becomes tricky. It’s not just about avoiding optimizing for speed, code size, memory usage, adaptability, or future-proofing. It’s about balance and whether your actions align with your values and goals. It’s completely contextual and sometimes impossible to measure objectively.

Why is this good? Because life is like this. It’s messy. Our programming minds crave order so much that we ironically create more chaos. It’s like forcing someone to love you. If you think you’ve done it, it’s not love. You’re also guilty of hostage-taking, probably need more love than ever, and this metaphor is wildly inappropriate.

If you think you’ve found the perfect system… enjoy the illusion. It’s fine, failures are learning opportunities.

Prioritizing UX

How does user experience fit into these priorities? Even desiring good performance is, ultimately, about UX.

In UI work, regardless of the framework or language, there’s always boilerplate and repetition. Reducing this can save programmer time and improve clarity. Here are two stories about balancing priorities.

At a previous company, we used a closed-source system with a rigid tech stack. The vendor refused UI customizations outside this stack, citing developer pain. I’ve never used it, so I won’t judge, but this “good for the programmer, bad for the user” trade-off was so burdensome for my colleagues that I wrote an add-on re-implementing that UI part. It was a massive productivity boost, and my colleagues loved it! Over a decade later, it’s still saving time and frustration.

I’m not saying opinionation is bad, just that too much was problematic for us. Conversely, Ruby on Rails’s appeal is its opinionated nature, providing direction in a front-end world with overwhelming choices. (Give me opinions until I form my own!)

On the other hand, you might be tempted to crown UX king. A noble goal, but here’s my second story.

Years after that successful project, a colleague asked me to automate a messy real-life scenario into a single-click solution. I started analyzing if an algorithm could even handle the edge cases without errors. The more we discussed it, the clearer it became that the effort wasn’t justified. This scenario arose maybe once a month, taking one person a few minutes to resolve. Even if we automated it flawlessly, the development and maintenance time would take ages to pay off in saved time. Saying “no” was tough for my people-pleasing side, but I had to end the discussion.

Let computers help users, but within reason. But how do you determine that reason?

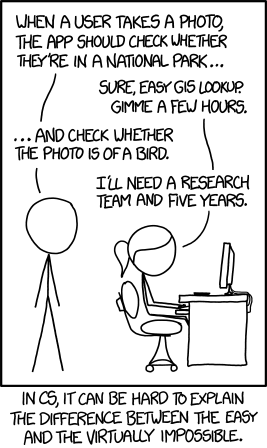

I recommend profiling the UX like your developers profile their code. Identify where users spend the most time repeating clicks or input and see if you can optimize those interactions. Can your code make educated guesses about their likely input and use that as a default? Except in certain situations (no-click EULA?), this can significantly improve user productivity and satisfaction. Conduct hallway usability testing if possible. It might be challenging to explain what computers can and can’t easily assist with, but this value is likely crucial to your users.

Avoiding Premature Optimization: When and How to Optimize

With other contexts explored, let’s assume we’re optimizing some aspect of raw machine performance for the rest of this article. My suggestions apply to other targets like flexibility, but each has its own caveats. Prematurely optimizing for anything is likely to fail.

So, regarding performance, what optimization methods should we actually follow? Let’s dive in.

This Isn’t a Grassroots Initiative, It’s Triple-A

In short: Work down from the top. Higher-level optimizations happen earlier in the project, while lower-level ones come later. That’s the essence of “premature optimization.” Deviating from this order risks wasting time and being counterproductive. You wouldn’t write an entire project in machine code from the get-go, right? So our AAA approach is to optimize in this sequence:

- Architecture

- Algorithms

- Assembly

It’s generally accepted that algorithms and data structures offer the most optimization potential, at least for performance. However, remember that architecture sometimes dictates which algorithms and data structures are even viable.

I once encountered software generating a financial report by repeatedly querying an SQL database for each transaction, then doing a simple calculation client-side. After just a few months of use by a small business, even their modest data volume meant that, with new desktops and a decent server, report generation took several minutes, and this report was frequently needed. I wrote a SQL statement incorporating the summing logic—bypassing their architecture by moving the work to the server—and even years later, my version generated the report in milliseconds on the same hardware.

Sometimes we lack control over a project’s architecture because it’s too late for changes. Sometimes developers can work around it, like I did. But at the start of a project, with architectural influence, that’s the time to optimize.

Architecture

Architecture is the most expensive part to change later, so optimizing early on makes sense. If your app needs to deliver data via ostriches, for instance, prioritize low-frequency, high-payload packets to avoid bottlenecks. You’d better have Tetris to entertain your users because a loading spinner won’t suffice! (Years ago, while installing Corel Linux 2.0, I was thrilled that the lengthy installation included exactly that. Having memorized Windows 95’s infomercial screens, this was refreshing.)

The unscalable SQL report example illustrates the cost of architectural changes. The app had evolved from MS-DOS roots and a custom, single-user database. When they finally adopted SQL, the schema and reporting code were seemingly ported directly. This left them with years of potential 1,000%+ performance gains to gradually implement as they fully transitioned to utilizing SQL’s advantages for each report. Great for business with locked-in clients, and clearly prioritizing coding efficiency during the transition. But meeting client needs about as effectively as a hammer turning a screw.

Architecture is partly about anticipating how your project needs to scale and in what ways. Being high-level makes concrete “dos and don’ts” difficult without specific technologies and domains.

I Wouldn’t Call It That, but Everyone Else Does

Fortunately, the internet is full of wisdom on every imaginable architecture. When it’s time to optimize yours, researching pitfalls often involves finding the buzzword for your vision. Someone likely had the same idea, failed, iterated, and blogged or wrote about it.

Buzzword identification through searching can be tricky. What you call a FLDSMDFR might be someone else’s SCOPWWHWTT, solving the same problem with different terminology. Developer communities to the rescue! Provide StackExchange or HashNode with a detailed description, including buzzwords your architecture isn’t, to show prior research. Someone will gladly enlighten you.

Meanwhile, some general advice might offer some valuable insights.

Algorithms and Assembly

With a suitable architecture, this is where your coders shine. Avoiding premature optimization still applies, but consider the specifics at this level. Implementation details are extensive, hence the separate article on code optimization for developers.

Once you’ve implemented something unoptimized for performance, do you leave it at Don’t do it and never optimize?

You’re right. The next rule, for experts only, is Don’t do it yet.

Time to Benchmark!

Your code works. Maybe it’s so slow you already know you need to optimize. Maybe you’re unsure, or you have an O(n) algorithm and assume it’s fine. Regardless, if optimization might be worthwhile, my advice is: Benchmark.

Why? Isn’t it obvious my O(n³) algorithm is worse than anything else? Two reasons:

- Add the benchmark to your test suite as an objective measure of your performance goals, whether they’re currently met.

- Even experts can accidentally make things slower. Even when it seems blatantly, painfully obvious.

Don’t believe me?

Outperforming $7,000 Hardware with $1,400 Hardware

Jeff Atwood of StackOverflow fame once pointed out that sometimes (usually, he argues) buying better hardware is more cost-effective than spending developer time optimizing. Let’s say you’ve objectively concluded this applies to your project. Your goal is to optimize compilation time for a large Swift project because it’s a major developer bottleneck. Time to shop for hardware!

What to buy? More expensive generally means better performance. So a $7,000 Mac Pro should compile faster than a mid-range Mac Mini, right?

Wrong!

It turns out that sometimes more cores mean faster compilation… but in this case, LinkedIn learned the hard way that the opposite was true for their setup.

Some make a further mistake: They don’t benchmark before and after the upgrade and find that the hardware didn’t make things “feel” faster. They have no concrete data and still can’t pinpoint the bottleneck, remaining unhappy with the performance after using their allocated time and budget.

Can I Optimize Now??

Yes, if you’ve decided it’s necessary. But that decision might wait until more/all algorithms are implemented. This way, you can see how everything interacts and which parts are most important via profiling. This might be at the app level for small projects or only within a subsystem. Remember, an algorithm might seem crucial, but even experts—especially experts—are prone to misdiagnosing this.

Think before You Disrupt

“I don’t know about you people, but…”

Consider applying the concept of false optimization more broadly: to your project, company, or even a sector of the economy.

It’s tempting to believe technology will save the day and that we’re the heroes who’ll make it happen. Plus, if we don’t, someone else will.

But power corrupts, despite good intentions. I won’t link specific articles, but seek out some on the broader impact of economic disruption and who ultimately benefits. The side-effects of optimizing the world might surprise you.

Postscript

Did you notice something, Optimus? I only called you Optimus at the beginning and now. You weren’t addressed by name throughout. Honestly, I forgot. I wrote the entire article without using it. When I realized at the end, a little voice said, don’t do it.