There are only two difficult tasks in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.

- Author: Phil Karlton

Caching Basics

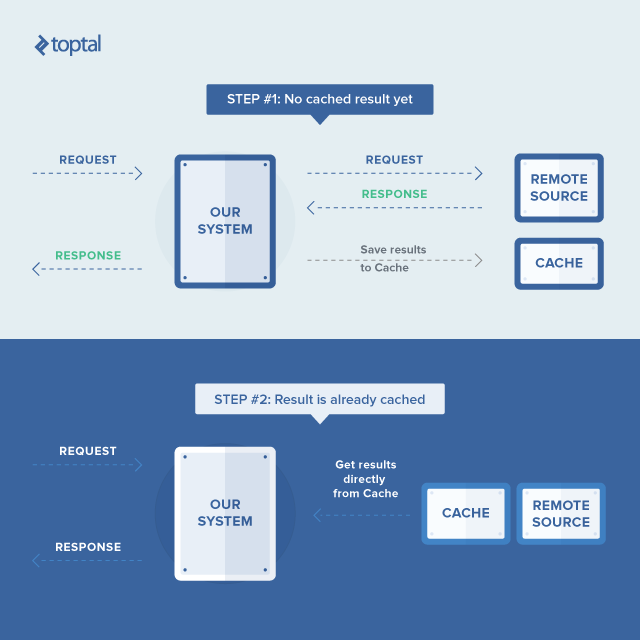

Caching is a powerful technique for improving performance by using a clever trick: Instead of performing expensive operations (like complex calculations or intricate database queries) every time we need a result, the system can store – or cache – the result of that operation and simply retrieve it the next time it is needed, thus responding much faster.

The effectiveness of caching relies on the validity of the cached results. This brings us to the core challenge: determining when a cached item is no longer valid and needs to be regenerated.

and perfect to solve distributed web farm caching problem.

Generally, a typical web application receives a significantly higher volume of read requests compared to write requests. Therefore, a typical web application designed to handle heavy traffic is built to be scalable and distributed, deployed as a cluster of web tier nodes, commonly known as a farm. These factors influence the practicality of caching.

This article examines the role of caching in ensuring high throughput and performance of web applications designed for high-load scenarios, drawing from my project experience and presenting an ASP.NET-based solution as a practical example.

Tackling High Load Challenges

The problem I faced was not unique. My goal was to enable an ASP.NET MVC monolithic web application prototype to manage a heavy workload.

Enhancing the throughput capabilities of a monolithic web application involves:

- Enabling parallel execution of multiple application instances behind a load balancer for efficient handling of concurrent requests (i.e., achieving scalability).

- Profiling the application to pinpoint and optimize performance bottlenecks.

- Implementing caching to boost read request throughput, as it typically constitutes a substantial portion of the overall application load.

Caching strategies frequently involve utilizing middleware caching servers like Memcached or Redis to store cached data. Despite their popularity and effectiveness, these approaches have drawbacks:

- Network latency when accessing dedicated cache servers can be comparable to database access latency.

- Web tier data structures might not be inherently suitable for serialization and deserialization. Using cache servers necessitates serializable data structures, demanding continuous development efforts.

- Serialization and deserialization introduce runtime overhead, negatively impacting performance.

These concerns were relevant to my situation, prompting me to seek alternative solutions.

ASP.NET’s built-in in-memory cache (System.Web.Caching.Cache) offers exceptional speed and eliminates serialization/deserialization overhead during development and runtime. However, it has limitations:

- Each web tier node maintains its own cache, potentially increasing database load during node startup or recycling.

- Cache invalidation on one node requires notifying all other nodes. Without proper synchronization in this distributed cache, most nodes might return outdated data, which is usually unacceptable.

If the increased database load is manageable, implementing a well-synchronized distributed cache seems relatively straightforward, right? While achievable, it’s not necessarily easy. In my case, benchmarks indicated the database tier wouldn’t be a bottleneck as most processing occurred in the web tier. Consequently, I opted for ASP.NET’s in-memory cache and focused on implementing effective synchronization.

ASP.NET-Based Solution

My approach utilized ASP.NET’s in-memory cache instead of a dedicated caching server. This meant each node in the web farm maintained its own cache, directly queried the database, performed necessary calculations, and cached the results. This ensured rapid cache operations due to its in-memory nature. Typically, cached items have a defined lifetime and become stale upon data changes or updates. Therefore, the web application logic usually dictates when a cache item needs invalidation.

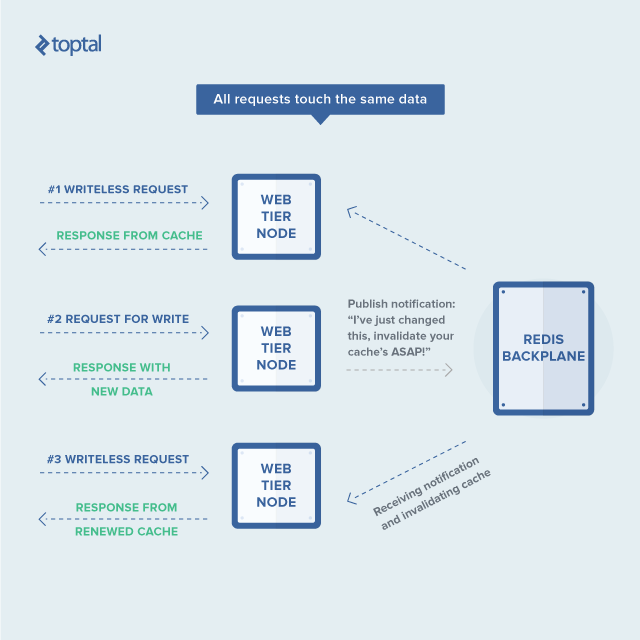

The remaining challenge was that invalidating a cache item on one node didn’t notify other nodes, leading to stale data being served. To address this, each node needed to broadcast cache invalidations to its peers. Upon receiving such an invalidation, other nodes could simply discard their cached value, fetching the latest data upon the next request.

This is where Redis comes in. Its strength lies in its Pub/Sub capabilities. Each Redis client can create a channel and publish data to it, allowing other clients to subscribe and receive that data, akin to event-driven systems. This functionality enables the exchange of cache invalidation messages between nodes, ensuring timely cache updates across the system.

ASP.NET’s in-memory cache is both simple and complex. It’s straightforward in its key/value pair structure but complex in its invalidation strategies and dependencies.

Fortunately, common use cases are usually simple, allowing for a default invalidation strategy for all items, limiting each cache item to a single dependency. My solution used the following ASP.NET code for the caching service interface (simplified and excluding proprietary details):

| |

This cache service allows storing results from a value getter function in a thread-safe manner and ensures the latest value is always returned. If a cache item becomes outdated or is evicted, the value getter is called again to retrieve the updated value. The ICacheKey interface abstracts cache keys, avoiding hardcoded key strings throughout the application.

For cache item invalidation, I introduced a separate service:

| |

Apart from methods for removing items with dependencies and updating key timestamps, there are “session”-related methods.

Our web application employed Autofac for dependency injection, implementing the inversion of control (IoC) pattern for dependency management. This freed developers from managing dependencies, as the IoC container handled that responsibility.

However, the cache service and cache invalidator have distinct IoC lifecycles. The cache service was registered as a singleton (shared instance), while the cache invalidator was registered as instance-per-request (separate instance per request).

This is due to another nuance: our Model-View-Controller (MVC) architecture separates UI and logic concerns. A controller action is typically wrapped in an ActionFilterAttribute subclass, used in ASP.NET MVC to decorate controller actions. This attribute managed database connections and transactions within each action.

Invalidating the cache mid-transaction could lead to race conditions where subsequent requests might repopulate the cache with outdated data. To prevent this, invalidations were deferred until the transaction committed, ensuring consistency and avoiding unnecessary cache modifications upon transaction failures.

This explains the “session”-related aspects of the cache invalidator and its request-bound lifecycle. The ASP.NET code looked like this:

| |

Here, PublishRedisMessageSafe sends a message (second argument) to a specific channel (first argument), with dedicated channels for drop and touch operations. The message handler performs the corresponding action based on the message payload.

Managing the Redis connection reliably was crucial. If the server went down, the application should gracefully handle it and seamlessly resume communication upon Redis’s recovery. This was achieved using the StackExchange.Redis library, with the connection logic implemented as follows:

| |

Here, ConnectionMultiplexer from StackExchange.Redis transparently handles the underlying Redis connection. Importantly, if a node loses connection, it reverts to a no-cache mode to prevent stale data. Upon connection restoration, it resumes utilizing the in-memory cache.

Here are examples of an action without caching (SomeActionWithoutCaching) and its caching counterpart (SomeActionUsingCache):

| |

A code snippet from an ISomeService implementation might look like:

| |

Benchmarking and Outcomes

With the caching mechanism in place, benchmarking was crucial to determine where to focus code refactoring for optimal caching benefits. We identified key use cases and used Apache jMeter to:

- Benchmark these use cases via HTTP requests.

- Simulate high load on the web node.

Performance profiling was done using a profiler capable of attaching to the IIS worker process, in my case, JetBrains dotTrace Performance. After fine-tuning jMeter parameters, we collected performance snapshots to identify hotspots and bottlenecks.

In several use cases, database reads consumed around 15%-45% of the overall execution time. Implementing caching resulted in near-doubled performance for most of these cases.

Conclusion

While this might seem like “reinventing the wheel” when established solutions like Memcached or Redis exist, it’s vital to consider their suitability before blindly applying them.

Thorough analysis of options and tradeoffs is essential for significant decisions. In this instance, multiple factors were at play, and a one-size-fits-all approach might not have been optimal.

Ultimately, implementing a tailored caching solution yielded a significant performance improvement of almost 50%.