Experts at Gartner suggest that roughly 70% to 80% of new business intelligence projects fail don’t succeed. This can be attributed to various factors, ranging from inappropriate tool selection to insufficient collaboration between IT teams and business stakeholders. Having personally overseen successful BI implementations across different sectors, I aim to use this blog post to share my insights and shed light on the common pitfalls that lead to business intelligence project failures. This article will outline strategies to mitigate these failures, grounded in three core principles that should guide the development of data warehouses. Adhering to these data warehouse concepts will equip you, as a data warehouse developer, with the knowledge to navigate the development process and steer clear of frequent obstacles and critical issues encountered during BI implementations.

Implementing a Business Intelligence Data Warehouse

Although the criteria for a successful business intelligence data warehouse may differ depending on the specific project, there are certain fundamental elements that are universally anticipated and essential for all projects. Let’s explore the key characteristics typically associated with a thriving business intelligence data warehouse:

- Value: Business intelligence projects can be extensive, often stretching over several months or even years. However, it’s crucial to demonstrate the tangible advantages of a data warehouse to your business stakeholders early on in the project. This early demonstration helps secure ongoing funding and maintain their interest. Ideally, stakeholders should witness some substantial business value derived from the new system within the initial three weeks of a project.

- Self-service BI: The era of relying solely on IT departments to fulfill data requests or conduct data analyses is fading. The success of any BI project is increasingly measured by its ability to empower business users to independently extract value from the system.

- Cost: BI projects generally involve considerable upfront implementation expenses. To counterbalance and offset these initial costs, it’s essential to design warehouses with an emphasis on low maintenance costs. If the client requires a dedicated team of BI developers to address data quality concerns, implement regular changes to data models, or manage ETL failures, the system can become financially burdensome and face the risk of being discontinued over time.

- Adaptability: The capacity to adapt to evolving business requirements is paramount. It’s crucial to recognize the multitude of BI tools available in the market and the rapid pace at which they evolve to incorporate new features and functionalities. Furthermore, businesses are constantly changing, leading to shifting requirements for the warehouse. Adaptability necessitates designing data warehouses in a way that allows for the future integration of alternative BI tools, such as different back-end or visualization tools, and accommodates often unanticipated changes in requirements.

Having accumulated experience from both successful endeavors and, perhaps even more instructively, unsuccessful projects, I’ve arrived at the understanding that three fundamental principles are essential for increasing the likelihood of successfully implementing a business intelligence system. But before delving into these principles, let’s establish some context.

Understanding Data Warehouses

Before we explore different data warehouse concepts, it’s essential to grasp the fundamental nature of a data warehouse.

Data warehouses are frequently perceived as business intelligence systems designed to support the daily reporting needs of a business entity. They don’t typically demand the same real-time performance capabilities (in standard implementations) as online transaction processing (OLTP) data systems. Additionally, while OLTP systems usually contain data related to a specific aspect of the business, data warehouses aim to encompass a comprehensive view of all data relevant to the business.

Data warehouse models only deliver substantial value to a business when the warehouse is treated as the central hub for “all things data,” extending beyond its role as a tool for generating operational reports. Establishing bidirectional communication between all operational systems and the data warehouse is critical. This allows operational systems to feed data into the warehouse and, in return, receive insights and feedback to improve operational efficiency. Any significant business adjustments, such as price increases or adjustments to supply and inventory, should be initially modeled and forecasted within the data warehouse environment. This proactive approach allows your business to make reliable predictions and quantify potential outcomes. In essence, all data science and data analytics functions should revolve around the data warehouse.

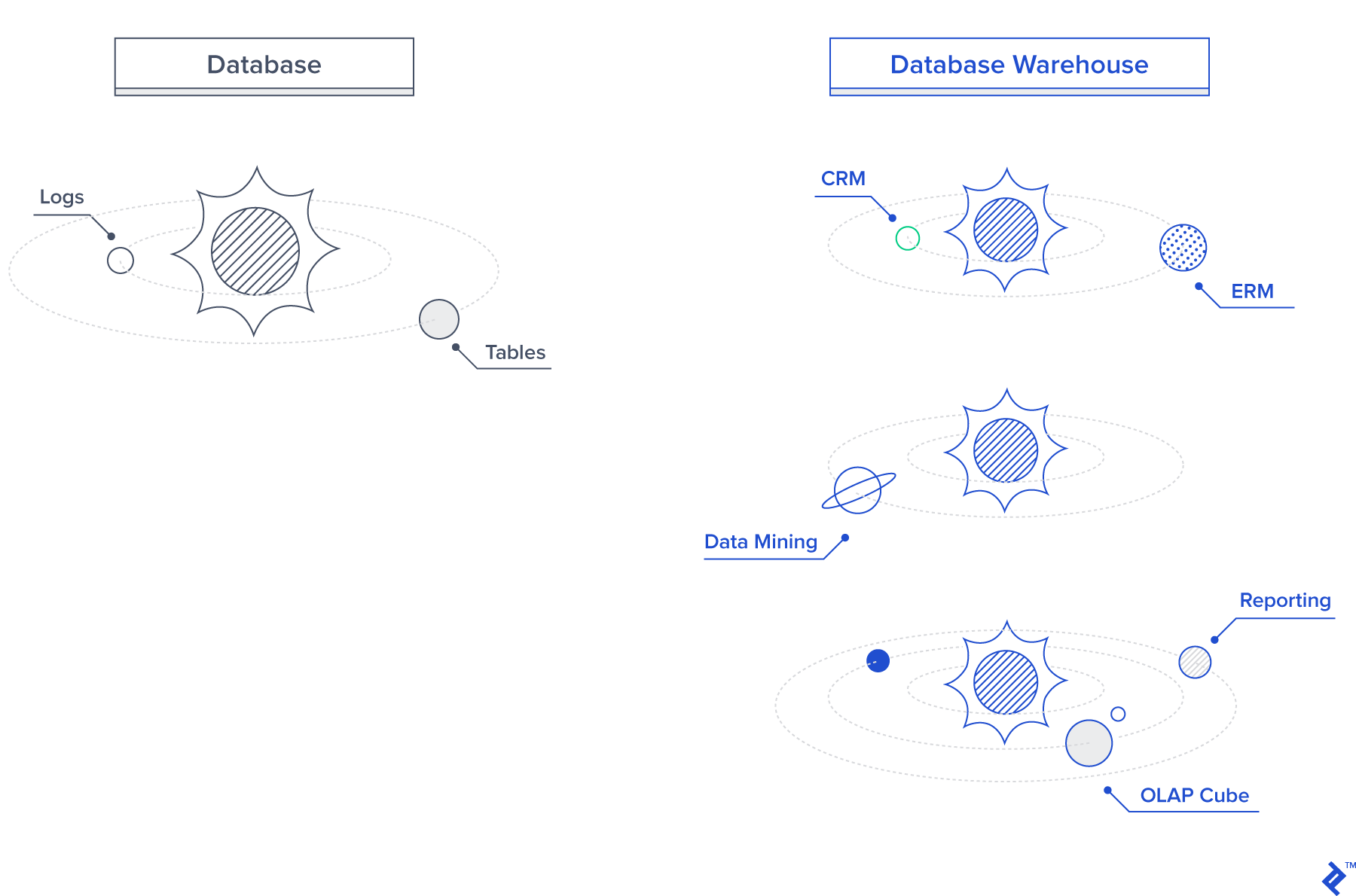

It’s important to note that a data warehouse encompasses various components and is not merely a database:

- A database serves as a repository for storing your data.

- A data warehouse extends beyond data storage by incorporating tools and components that facilitate the extraction of meaningful business value from your data. These components might include integration pipelines, data quality frameworks, visualization tools, and even machine learning plugins.

To further illustrate the distinction, let’s visualize the difference between a database and a data warehouse structure. Databases, or newer logical data meta stores like Hive, act as the central star in a data warehouse’s ecosystem, with all other components orbiting like planets. However, unlike a star system, a data warehouse can have multiple databases, and these databases should be adaptable and interchangeable with emerging technologies. We’ll elaborate on this concept later in the article.

Prioritizing Data Quality: The First Data Warehouse Principle

Data warehouses are only as useful and valuable as the trust business stakeholders place in the accuracy and reliability of the data they contain. To foster this trust, it’s crucial to establish frameworks that can automatically identify and, whenever possible, rectify data quality issues. Data cleansing should be an integral part of the data integration process, complemented by regular data audits and data profiling to detect potential issues. While these proactive measures are essential, it’s equally important to have reactive measures in place for instances where inaccurate data manages to bypass these safeguards and is flagged by users.

To maintain user confidence in the data warehouse system, any data quality issues reported by business users should be promptly investigated and addressed as a top priority. To facilitate this process, incorporating data lineage and data control frameworks into the platform is essential. These frameworks help ensure that any data discrepancies can be swiftly traced back to their source and resolved by the support team. Fortunately, most data integration platforms offer some degree of built-in data quality solutions, such as Data Quality Services (DQS) in Microsoft SQL Server or IDQ in Informatica.

Leveraging these built-in platforms is recommended if you’re utilizing commercial tools within your data integration pipelines. However, regardless of whether you utilize these pre-built solutions, it’s crucial to establish mechanisms that support your efforts in maintaining data quality. As an example, many data integration tools lack comprehensive data lineage tracking capabilities. To address this limitation, a custom batch control framework can be developed using a series of control tables. These tables meticulously track every data flow within the system, providing a clear audit trail.

Remember, regaining the trust of your business stakeholders after they’ve encountered data quality issues within your platform is an uphill battle. Therefore, the upfront investment in robust data quality frameworks is a prudent decision that yields substantial long-term benefits.

The Second Data Warehouse Principle: Inverting the Triangle

Let’s examine a common scenario in data warehouse implementations:

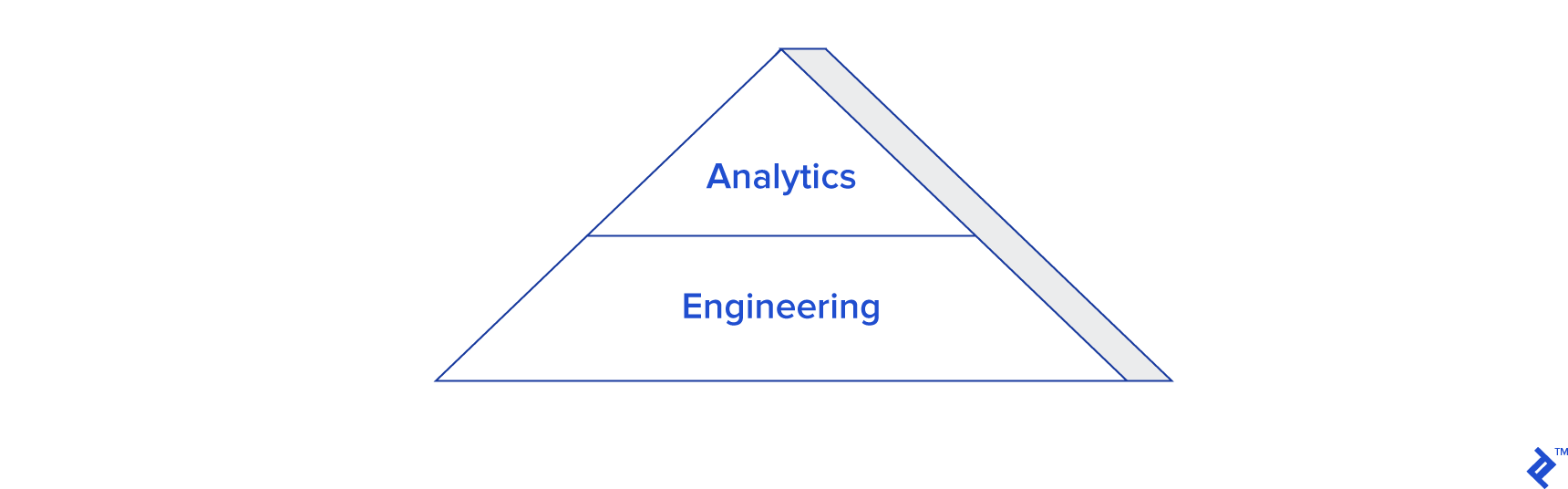

This illustration depicts a common distribution of effort in the implementation and utilization of many data warehouses. A significant portion of the effort is dedicated to building and maintaining the warehouse, while the value-added activities associated with using the warehouse for business analytics constitute a much smaller proportion. This imbalance is another contributing factor to the failure of many business intelligence projects. Sometimes, the project timeline extends for far too long before any tangible value can be demonstrated to the client. Moreover, even when the system is finally deployed, extracting business value from it often requires substantial IT involvement. As emphasized earlier, designing and implementing business intelligence systems can be both expensive and time-consuming. Therefore, it’s only natural for stakeholders to expect a swift realization of the value proposition associated with their business intelligence and data warehousing investments. If tangible value fails to materialize, or if the results are delayed to the point of becoming irrelevant, stakeholders might be compelled to withdraw support and discontinue the project.

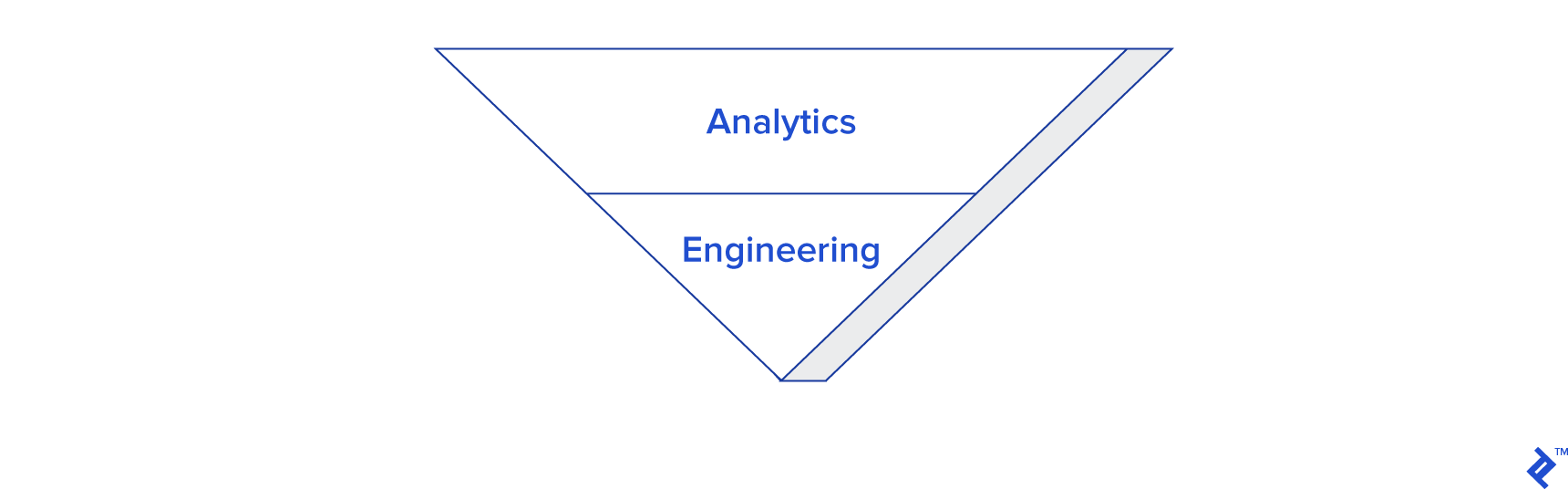

This brings us to the second principle of data warehouse development: inverting the triangle, as depicted here:

The selection of business intelligence tools and the implementation of appropriate frameworks should prioritize maximizing the effort allocated to extracting business value from the warehouse, as opposed to focusing primarily on its construction and maintenance. This shift in approach ensures high levels of engagement from business stakeholders, as they will quickly recognize the value proposition and return on investment. More importantly, it fosters self-sufficiency within the business, enabling users to derive insights without heavy reliance on IT.

This principle can be effectively implemented by adopting incremental development methodologies during the warehouse construction phase. This iterative approach ensures that production-ready functionalities are delivered as rapidly as possible. Implementing strategies like Kimball’s data mart methodology or the Linstedt’s Data Vault data warehouse design approach facilitates the development of systems that scale incrementally while seamlessly accommodating changes. Incorporating a semantic layer into your platform, such as a Microsoft SSAS cube or a Business Objects Universe, provides an intuitive and user-friendly business interface to your data. In the case of using a semantic layer like an SSAS cube, you also simplify the process for users to query data from Microsoft Excel, which remains a widely used data analytics tool.

Furthermore, integrating BI tools that emphasize self-service BI, such as Tableau or PowerBI, can significantly enhance user engagement. These tools streamline the data querying process, making it considerably more intuitive compared to writing SQL queries.

Another effective strategy is to store source data in a data lake environment before loading it into a database. This approach provides users with early access to the source data during the onboarding process. Advanced users, such as business analysts and data scientists, can then directly analyze the source data (in its raw file format) by connecting tools like Hive or Impala. By granting early access to raw data, you can potentially reduce the time it takes for the business to analyze a new data point from weeks to days or even hours.

Embracing Adaptability: The Third Data Warehouse Principle

In the current digital landscape, data is rapidly becoming the digital equivalent of oil, signifying its immense value and potential. Recent years have witnessed an explosion in the number of tools available for building data warehouse platforms, accompanied by a relentless pace of innovation. Leading this charge is the vast array of data visualization tools currently on the market, closely followed by advancements in back-end technologies. Given this dynamic environment and the constant evolution of business requirements, it’s paramount to acknowledge the inevitability of change. You’ll likely need to swap out components of your technology stack, or even introduce or remove entire tools, over time, as dictated by evolving business needs and technological advancements.

Based on my personal experience, if a platform can remain operational for 12 months without requiring some form of significant modification, consider it a fortunate exception. A reasonable amount of effort is inherently unavoidable when adapting to change. However, it should always be feasible to modify technologies or designs without undue burden. Your platform should be inherently designed to accommodate this eventuality. If the cost of migrating a warehouse becomes prohibitively expensive, the business might deem the investment unjustified and choose to abandon the existing solution rather than migrating it to newer tools.

While it’s impossible to construct a system that anticipates and flawlessly caters to every conceivable future need, it’s essential to approach data warehouse development with the understanding that what you design and build today might need to be replaced or significantly modified in the future. With this in mind, I advocate for the use of generic tools and designs whenever feasible, rather than tightly coupling your platform to the specific tools it relies on at any given time. Of course, this decision should be made after careful planning and consideration, as the strength of many tools, particularly databases, lies in their unique capabilities and complementary features.

For instance, ETL performance can be drastically enhanced by leveraging stored procedures within a database to generate new business analytics data. This approach is often more efficient than extracting and processing data outside the database using languages like Python or tools like SSIS. In the realm of reporting, different visualization tools offer distinct functionalities that might not be readily available in others. For example, Power BI supports custom MDX queries, a feature not directly available in Tableau. However, my intention is not to discourage the use of stored procedures, SSAS cubes, or Tableau within your systems. Instead, I aim to emphasize the importance of making conscious and well-justified decisions when choosing to tightly integrate your platform with specific tools, always considering the long-term implications.

Another potential pitfall lies in the integration layer. Opting for a tool like SSIS for data integration might seem appealing due to its debugging capabilities and seamless integration with the SQL Server platform. However, migrating hundreds of SSIS packages to a different tool in the future could balloon into a costly and complex undertaking. In situations where you primarily focus on “EL” (Extract and Load) operations, consider using a more generic tool for processing. For example, utilizing a programming language like Python or Java to create a single, versatile loader for your staging layer can significantly reduce the reliance on numerous individual SSIS packages. This approach not only minimizes maintenance overhead and future migration costs but also facilitates automation in the data onboarding process, as you eliminate the need to develop new packages for each data source. This aligns with the principles of efficiency and adaptability we’ve discussed earlier.

In essence, when making architectural and tooling decisions, always strive to strike a balance between the immediate benefits and the potential future costs associated with migration. This balanced approach ensures that the data warehouse remains adaptable and doesn’t become obsolete due to an inability to accommodate change or because the cost of change becomes prohibitively expensive.

In Conclusion

The failure of business intelligence systems can be attributed to a multitude of factors, and there are common oversights that can set the stage for eventual failure. These include the constantly evolving technology landscape, budgetary constraints imposed on data systems due to the misconception that they are of secondary importance compared to operational systems, and the inherent complexities of working with data. These challenges highlight the need for meticulous consideration of not only immediate goals but also long-term plans during the design and development of a data warehouse’s components.

The fundamental principles of data warehousing outlined in this article provide valuable guidance for navigating these critical considerations. While adhering to these principles doesn’t guarantee absolute success, they serve as a robust framework to help you avoid common pitfalls and increase the likelihood of implementing a successful and sustainable business intelligence system. By prioritizing data quality, inverting the traditional effort triangle to focus on value extraction, and embracing adaptability in your design and tool selection, you lay a solid foundation for a data warehouse that can effectively support your organization’s analytical needs both today and in the future.