It’s no secret: Android Wear isn’t doing well at all. Despite being available for a year and a half, and launching before Apple’s smartwatch, the platform is struggling.

So what’s behind Android Wear’s poor performance and what are the implications for developers?

Several factors, such as insufficient Google development and subpar hardware, have hampered growth. While some of these have been or are being addressed, others can’t be resolved with current technology.

Android Wear Sales Are Underwhelming

Just how bad are sales? Android Wear launched on March 18, 2014, but devices didn’t hit shelves until months later. By late 2014, more appealing models like the circular Moto 360 and LG G Watch R, alongside rectangular options from major brands like Sony and Asus, became available. Unfortunately, this didn’t boost sales, and 2014 ended with a dismal estimated 720,000 units sold. Apple, on the other hand, surpassed Google within months, selling an estimated 3.6 million Apple Watches by mid-2015.

As reported by market research company IDC, Apple became the second largest wearable vendor in Q2, capturing a 20 percent market share, trailing only Fitbit in total sales. Notably, no Android Wear product made IDC’s top five wearables list. Apple was followed by Chinese smartphone manufacturer Xiaomi, navigation and sports watch specialist Garmin, and Samsung in fifth place (selling Tizen smartwatches instead of Android Wear).

Analyst opinions on smartwatch sales are mixed, but many research firms have adjusted their initially optimistic predictions to reflect the declining demand. Most now anticipate Apple Watch sales to reach nine to 14 million units in 2015, while Android Wear is projected to lag behind with four to six million units. Looking at Google Play, the number of Android Wear app downloads falls within the one to five million range. With two months left in the year, a conservative estimate of four million units seems likely.

While Apple may be leading, I wouldn’t consider their Apple Watch sales figures remarkable. Given their massive user base, shipping just over ten million devices in the first year isn’t impressive. Furthermore, some optimistic (and potentially biased) analysts predicted Apple would sell over 40 million smartwatches in their first year. At this pace, reaching 40 million units annually will take years, but that won’t diminish Apple’s likely Pyrrhic victory.

Is 2016 the Year of Android Wear?

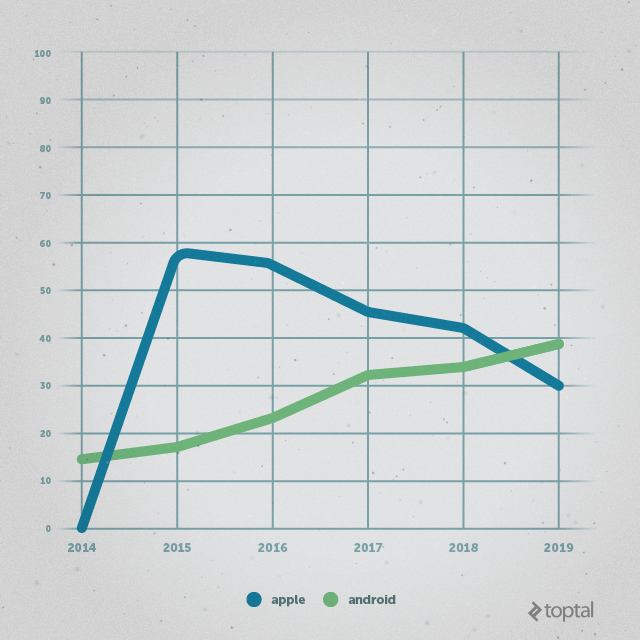

Considering the low demand for expensive Apple and Google smartwatches, should we expect any improvements in the coming year? Analysts believe sales will increase in 2016 and beyond. IDC forecasts Apple will ship around 40 million smartwatches in 2019, up from an estimated 13.9 million this year. Apple is projected to end 2015 with a 58.3 percent market share, while Android Wear is predicted to capture only 17.4 percent with 4.1 million units sold.

IDC also examined other platforms, including Pebble OS, RTOS, and Tizen. They anticipate Pebble OS and Tizen shipments remaining stagnant, resulting in market share declines to 3.1 and 2.2 percent, respectively.

IDC and other firms predict Android Wear will gain momentum, reaching 38.4 percent market share by 2019, with a 67.5 percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR), compared to the estimated 30.6 percent CAGR for Apple Watch.

Therefore, Android Wear appears poised for long-term success. This conclusion doesn’t require extensive market analysis; observing historical trends in the smartphone and tablet markets reveals how Android consistently gains market share over Apple.

The smartwatch market as a whole is set for rapid expansion, with one particularly bullish forecast predicting global shipments reaching a staggering 373 million units in 2020. While I approach this figure with caution (as a non-economist, I have reservations about the methodology and the inclusion of devices that might not qualify as true smartwatches), 2019 and 2020 are still far off.

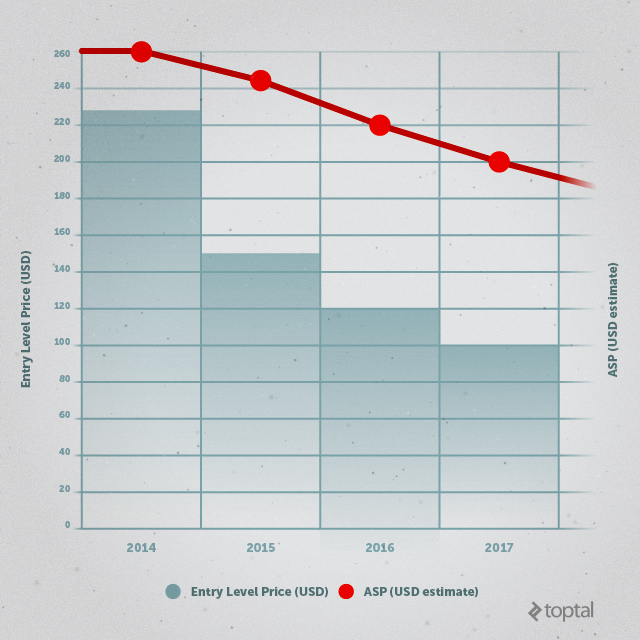

So, what can we expect in 2016? While publicly available research on Android Wear sales in 2016 is limited, several trends have emerged. Rather than directly competing with the premium Apple Watch, Android Wear manufacturers seem to be targeting mainstream adoption by positioning their devices as affordable yet practical gadgets. This makes sense considering smartwatches are essentially disposable electronics, despite costing as much as a high-quality quartz watch from a respected brand, unlike mechanical watches built to last for decades.

One example of this shift is the new Asus ZenWatch 2, which retails on Google Play for $149, a third of the price of the entry-level Apple Watch. This affordability doesn’t necessitate significant compromises, and initial reviews are favorable. It offers essentially the same functionality as a $300 smartwatch, albeit in a larger package and lacking the sleek design of the Moto 360 or LG Urbane.

However, major brands won’t dominate the Android Wear market indefinitely. Taiwanese chipmaker MediaTek is enabling smaller Chinese vendors by offering its own Android Wear solutions based on its MT2601 system-on-chip (SoC). Initial product announcements have surfaced, with some vendors stating their MediaTek-powered smartwatches will launch by year’s end. These watches boast hardware nearly identical to their brand-name counterparts, utilizing the same high-resolution displays, with some featuring all-metal construction and circular displays. Others differentiate themselves with additional sensors or durable casings. The most compelling aspect? The first models I examined were metal watches with round displays priced between $110 and $130, a fraction of the cost of comparable models from Motorola, LG, and Huawei.

What I find most intriguing about these designs is their versatility and variety. Why must all smartwatches emulate traditional watches with elegant designs? Why not have sports watches with built-in thermometers, barometers, and location sensors? Or affordable, durable watches for children and teenagers?

This diversity and ability to cater to specific niches present opportunities for both hardware manufacturers and developers. By leveraging additional onboard sensors, possibilities range from apps for kids to specialized tools for mountaineers and athletes. While major brands will likely maintain their leadership, I’m excited to see the impact of $100 and sub-$100 Android Wear watches. These devices have the potential to expand the ecosystem and introduce the platform to new markets and demographics, such as budget-conscious youngsters and millions of consumers in emerging economies.

It’s important to note that Google prohibits its hardware partners from significantly altering Android Wear with custom skins or bloatware. This policy aims to ensure a consistent user experience across all devices, from stylish $500 watches to $100 models produced by lesser-known Chinese companies.

What Does This Mean for Developers?

A previous article explored the viability of developing for Android Wear and other smartwatch platforms.

The smartwatch market is poised for continuous growth and evolution in the long term. However, developers shouldn’t prioritize Android Wear support just yet. While acquiring new skills and mastering new platforms is always beneficial, realistically, Android Wear won’t gain significant traction for another year or two.

This doesn’t imply a lack of development on the Android Wear front. Google continues to release incremental updates, and developers are actively creating new apps and use-cases for Google’s smartwatches. Designers are busy crafting hundreds of unique watch faces for both round and rectangular displays.

Google consistently refines the platform and introduces new features. For instance, Google Play Services 8.1 grants developers access to an always-on mode for the Google Maps Android API. This requires adding WAKE_LOCK permissions to the app manifest and a few dependencies. With just a few lines of code, you can check out the official guide here, complete with documentation and sample code.

Google regularly updates its Android Wear emulators, enabling developers to test their creations on various devices with different screen sizes, form factors, and pixel densities. This will be crucial as more devices from smaller vendors emerge. I’m aware many developers are apprehensive about dealing with numerous new devices each month and grappling with Android fragmentation yet again. I’ll address this concern in the hardware section.

While x86-based Android Wear hardware is currently nonexistent, Google encourages developers to future-proof their apps by incorporating support for the x86 instruction set. This involves modifying the abiFilters in the build.gradle file to abiFilters = ['armeabi-v7a','x86'] and recompiling the app.

One of Google’s Android Wear community moderators, Wayne Piekarski, has a GitHub project that showcases this functionality in a real-world scenario.

This brings us to our next topic: Hardware.

Android Wear Hardware Evolution

Unlike Android smartphones, which seem to receive new chips every few months, wearable hardware development progresses at a much slower pace. The core hardware platform hasn’t changed significantly since Google and LG introduced the first Android Wear devices in early 2014. The formula remains consistent: a Qualcomm Snapdragon 400 processor, 512MB of RAM, 4GB of storage, a few sensors, and a high-density display.

The most significant variation lies in the form factor, with some manufacturers opting for circular watches (LG) while others prefer rectangular displays (Asus). Display resolutions vary, ranging from 320 by 320 to 400 by 400 pixels. Increasing display resolution beyond this point is impractical for such devices, as it would drive up costs and reduce battery life without providing tangible benefits to the user experience. Although resolution is unlikely to increase in the next year or two, we can anticipate the adoption of more energy-efficient OLED displays and Force Touch technology.

Display size will also likely remain unchanged. Smartwatches are already relatively bulky, so there’s little reason to increase their size further. Smaller, thinner watches targeting fashion-conscious consumers, or models with smaller faces designed for women, would be a welcome addition to the market. Unfortunately, current mobile technology limits the feasibility of such devices without significant compromises, primarily in battery capacity. This would be counterproductive, given that battery life is already a major weakness for smartwatches.

However, improvements are on the horizon. The Snapdragon 400 and MediaTek MT2601 are both 28nm processors. As manufacturing costs decrease, we can expect to see 14/16nm FinFET chips replacing them, leading to improved battery life.

What about Intel’s x86 chips? While Intel already utilizes more advanced manufacturing nodes for its latest mobile processors (22nm for Moorefield, 14nm for Cherry Trail), this alone doesn’t guarantee superior battery efficiency. Based on my experience testing Android devices powered by various Intel mobile processors over the past two years, including the latest Cherry Trail chips, I haven’t observed significant efficiency gains compared to ARM processors manufactured using older, planar 28nm nodes. Simply put, x86 chips aren’t as efficient as their ARM counterparts, particularly in low-power devices. While Intel could invest in developing a groundbreaking chip for Android Wear and other wearables, it’s questionable whether they would. Securing a foothold in a niche market would require significant financial investment, a risk Intel typically avoids.

Conclusion: The Smartwatch User Base Will Remain Limited

The smartwatch industry faces several significant hurdles, and the short-term outlook isn’t promising. This doesn’t mean Android developers and designers should avoid the smartwatch market altogether. However, this emerging sector won’t be as lucrative as some optimistic analysts predicted a year ago.

If you planned to dedicate significant time and effort to smartwatch development, it might be wise to reconsider. While every new market presents opportunities, and some will undoubtedly find success with killer apps for next-generation wearables, widespread investment will remain limited as long as the user base remains small.

Hardware, especially in terms of efficiency and battery life, requires improvement. Software is advancing but still has a long way to go. These issues will eventually be addressed, but in my opinion, they aren’t the primary obstacle confronting smartwatch manufacturers. The fundamental question is whether consumers actually need such devices. As it stands, most users can live comfortably without them.

Currently, there are limited compelling use cases for smartwatches and wearables in general, beyond fitness tracking and a few niche applications. Purchasing a $250 Android Wear watch with limited battery life and minimal functionality not already available on a standard smartphone isn’t an appealing proposition for most consumers. And that’s unlikely to change anytime soon.