Professor Justin Borg-Barthet, University of Aberdeen*

*Advisor to a coalition of press freedom NGOs on the introduction of SLAPPs, co-author of the CASE Model Law, lead author of a study commissioned by the European Parliament, and member of the Commission’s Expert Group on SLAPPs and its legislative sub-group

Background

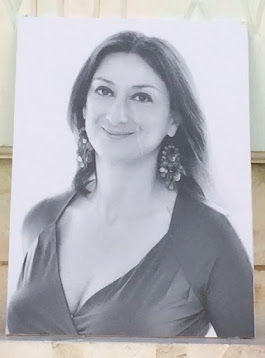

At the time of her assassination on October 16, 2017, Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia faced 48 defamation lawsuits across various courts. Her investigative journalism, which exposed corruption within the government and private sector, made her a target of retaliatory litigation intended to silence her. These legal actions, often lacking merit, burdened Caruana Galizia and discouraged others from similar investigative work.

The abuse faced by Caruana Galizia brought attention to the issue of SLAPPs (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation), lawsuits aimed at stifling public scrutiny through legal burdens rather than genuine legal claims. Primarily using defamation laws but also leveraging privacy and intellectual property claims, SLAPPs exploit legal processes to intimidate critics and discourage public participation.

Responding to this growing concern, several jurisdictions, including US states, Canadian provinces, and Australian states and territories, enacted anti-SLAPP laws to enable early case dismissal and provide cost-shifting measures to protect SLAPP targets. Despite the lack of such laws in EU member states, the issue gained traction among European NGOs and MEPs, who advocated for legal solutions within the European Union.

Initially hesitant, the European Commission, citing jurisdictional limitations, resisted calls for anti-SLAPP legislation. However, with mounting evidence and political shifts within the Commission, their stance changed, leading to the introduction of anti-SLAPP measures on April 27, 2022. This included a proposed “Daphne’s Law,” an anti-SLAPP Directive.

This proposed legislation draws inspiration from a Model Law commissioned by the Coalition Against SLAPPs in Europe (CASE), a collection of NGOs advocating for anti-SLAPP measures in Europe. This Model Law, influenced by existing anti-SLAPP legislation in the United States, Canada, and Australia, considers European legal traditions and benefits from expert consultation.

Legal Basis and Scope

Convincing the Commission to address SLAPPs required demonstrating the EU’s legal authority to intervene. While initially debated, the Commission recognized the internal market impact of SLAPPs and adopted a stronger stance against their threats to the rule of law and human rights. Various legal arguments were presented, including basing the legislation on multiple treaty articles, highlighting the internal market effects of SLAPPs, and utilizing provisions related to cross-border legal cooperation. Ultimately, the Commission’s proposal relies on Article 81 TFEU, which addresses judicial cooperation in civil matters, given the anticipated resistance from member states towards interference in their domestic procedural laws.

Traditionally, Article 81 TFEU applies to cases with international elements. Therefore, the proposed directive confines its scope to cross-border cases, initially considering the domicile of the involved parties. However, Article 4(2) introduces a significant expansion:

Where both parties to the proceedings are domiciled in the same Member State as the court seised, the matter shall also be considered to have cross-border implications if:

a) the act of public participation concerning a matter of public interest against which court proceedings are initiated is relevant to more than one Member State, or

b) the claimant or associated entities have initiated concurrent or previous court proceedings against the same or associated defendants in another Member State.

Recognizing that SLAPPs can impact matters beyond the parties directly involved, the Commission’s proposal adopts an expansive approach. This is crucial in the interconnected EU, where transnational public interest can be a factor.

This broad scope could widen further as member states incorporate the directive into their national laws. Ideally, member states would apply these measures to both cross-border and domestic cases, preventing discrimination against SLAPP victims in solely domestic disputes and minimizing legal disputes regarding the definition of “[relevance] to more than one Member State” in Article 4(2)(a).

Defining SLAPPs

Interestingly, the term “SLAPPs” is absent from the directive’s main text, appearing only in the title and preamble. This decision stems from concerns about the term’s unfamiliarity within European legal contexts and potential confusion regarding the implication of a deliberate “strategy.” Instead, the directive, mirroring the Model Law, uses the phrase “abusive court proceedings against public participation,” focusing on the lawsuit’s abusive nature.

Identifying cases falling under this directive requires determining if they involve “public participation” on a “matter of public interest.” Recognizing that SLAPPs target a broad range of actors, including journalists, civil society organizations, academics, and individuals, the directive broadly defines these terms in Article 3:

‘public participation’ means any statement or activity by a natural or legal person expressed or carried out in the exercise of the right to freedom of expression and information on a matter of public interest, and preparatory, supporting or assisting action directly linked thereto. This includes complaints, petitions, administrative or judicial claims and participation in public hearings;

‘matter of public interest’ means any matter which affects the public to such an extent that the public may legitimately take an interest in it, in areas such as:

a) public health, safety, the environment, climate or enjoyment of fundamental rights;

b) activities of a person or entity in the public eye or of public interest;

c) matters under public consideration or review by a legislative, executive, or judicial body, or any other public official proceedings;

d) allegations of corruption, fraud or criminality;

e) activities aimed to fight disinformation;

If a case involves public participation in a matter of public interest, the next step is determining if the proceedings are abusive, as defined by Article 3:

‘abusive court proceedings against public participation’ mean court proceedings brought in relation to public participation that are fully or partially unfounded and have as their main purpose to prevent, restrict or penalize public participation. Indications of such a purpose can be:

a) the disproportionate, excessive or unreasonable nature of the claim or part thereof;

b) the existence of multiple proceedings initiated by the claimant or associated parties in relation to similar matters;

c) intimidation, harassment or threats on the part of the claimant or his or her representatives.

Therefore, abuse is defined by two key elements: (i) claims lacking merit (fully or partially) and (ii) the use of harassing tactics by the claimant. Determining the type of abuse influences the available remedies, with stronger responses applied to demonstrably unfounded claims.

Main legal mechanisms to combat SLAPPs

Once a court identifies proceedings as SLAPPs within the directive’s scope, the defendant has access to three key remedies: (i) security for costs and damages during the proceedings, (ii) early dismissal of the case, and (iii) reimbursement of costs and damages.

Early dismissal is considered crucial in anti-SLAPP legislation, as it prevents the plaintiff from financially and psychologically burdening the defendant by prolonging the case. However, this remedy requires careful consideration, as it could potentially infringe upon the plaintiff’s right to access courts. The proposed directive addresses this by limiting early dismissal to cases where the claim is demonstrably unfounded, in whole or in part, requiring the plaintiff to prove their claim has merit (Art 12).

When a claim is not deemed manifestly unfounded, early dismissal is not applicable, even if the primary objective is to stifle public participation (as evidenced by factors like disproportionate claims, multiple lawsuits, or harassment by the plaintiff). This differs from the Model Law, which permits early dismissal for cases lacking merit but displaying abusive characteristics. The Model Law argues that courts should be able to dismiss cases misused to harass rather than uphold rights, asserting that this does not hinder legitimate access to courts but deter abuse. While the Commission’s cautious approach is understandable, the high threshold of proving manifest unfoundedness may allow some abuse to persist.

Other remedies, such as requiring the plaintiff to provide security for costs and damages (Article 8) and holding them liable for costs, penalties, and damages (Articles 14-16), partially address this shortcoming. These financial remedies, applicable regardless of whether a SLAPP is manifestly unfounded or simply abusive, offer some assurance to the defendant that they will be compensated for losses incurred due to the lawsuit. These measures are also expected to deter potential SLAPP filers who would be reluctant to compensate those whose free expression they aimed to suppress. However, it is crucial to emphasize that these remedies should complement, not replace, early dismissal as a primary solution.

Beyond these primary mechanisms, the directive includes additional procedural safeguards. These include restrictions on amending claims to avoid cost liability (Recital 24 and Article 6) and the right for third parties to intervene (Article 7). The latter allows NGOs to submit amicus briefs in cases involving public participation. While seemingly minor, this provision could significantly benefit more vulnerable defendants (and less experienced courts) by providing valuable expertise and oversight.

London Calling: Private International Law Innovation

While these provisions deter SLAPPs within EU courts, a significant gap remains regarding protection against SLAPPs filed in non-EU countries. London, with its high litigation costs and plaintiff-friendly defamation laws, is a particularly attractive jurisdiction for those seeking to stifle scrutiny. Similarly, other jurisdictions might appeal to plaintiffs wanting to circumvent EU anti-SLAPP measures, due to factors such as the challenges of transnational litigation or specific local laws. To address this, the directive proposes harmonized rules on handling third-country SLAPP litigation.

Article 17 stipulates that enforcing judgments from non-EU courts should be refused on public policy grounds if the proceedings exhibit SLAPP characteristics. Although member states already had the authority to refuse enforcement in such cases, this article ensures universal protection against enforcing judgments resulting from abusive lawsuits.

Furthermore, Article 18 introduces a novel harmonized jurisdictional rule and establishes the right to damages in cases involving SLAPPs filed in non-EU courts. This provision grants jurisdiction to courts in the SLAPP victim’s domicile, irrespective of the plaintiff’s location, providing robust protection against the misuse of foreign courts and reducing the appeal of jurisdictions like London and the United States for silencing journalists.

While limiting forum shopping concerning non-EU countries is positive, a significant loophole remains within the European judicial area due to EU law and the Lugano Convention. The combined effect of EU private international law on defamation allows litigants to exploit transnational litigation to suppress free speech. Consequently, NGOs have proposed amending two EU private international law instruments:

Firstly, the Brussels I Regulation (recast) should be amended to base jurisdiction in defamation cases on the defendant’s domicile, preventing plaintiffs from exploiting their ability to choose courts with minimal connection to the dispute;

Secondly, addressing the exclusion of defamation from the Rome II Regulation, which subjects journalists to potentially weaker free speech protections, necessitates a new rule mandating the application of the law where the publication is directed;

These changes are yet to be implemented. Hopefully, ongoing reviews of these instruments will bring positive developments for public participation within the EU.

Concluding remarks

Daphne’s Law now awaits approval from the Council of Ministers and the European Parliament. The legislative process might involve the Parliament advocating for stronger measures while member states may seek to preserve procedural autonomy. The Commission’s draft attempts to strike a balance between these positions, but refinements are expected during the approval process. As mentioned, expanding early dismissal beyond demonstrably unfounded cases would strengthen the directive. Ultimately, this directive represents a positive first step in combating SLAPPs in Europe, and further reviews of private international law instruments are anticipated.

Photo credit: ContinentalEurope, on Wikicommons