C++ programmers aim to create strong multithreaded applications with Qt, but multithreading is tricky due to race conditions, synchronization issues, deadlocks, and livelocks. Determined developers often turn to StackOverflow for solutions. However, finding the ideal solution from numerous answers can be challenging, especially considering each solution’s drawbacks.

Multithreading is a popular programming and execution model enabling multiple threads within a single process. These threads share process resources while executing independently. The model provides a useful abstraction of concurrent execution for developers. Additionally, multithreading facilitates parallel execution on multiprocessing systems using a single process.

This article aims to compile essential knowledge about concurrent programming in the Qt framework, particularly focusing on commonly misunderstood areas. Readers should have prior Qt and C++ experience to grasp the content.

Selecting Between QThreadPool and QThread

Qt offers various multithreading tools, making the choice difficult initially. However, the decision-making boils down to two options: letting Qt manage threads or managing them manually. Several key factors influence this decision:

Tasks that don’t require the event loop, specifically those not using signal/slot mechanisms during execution. Use: QtConcurrent and QThreadPool + QRunnable.

Tasks employing signal/slots, thus needing the event loop. Use: Worker objects moved to + QThread.

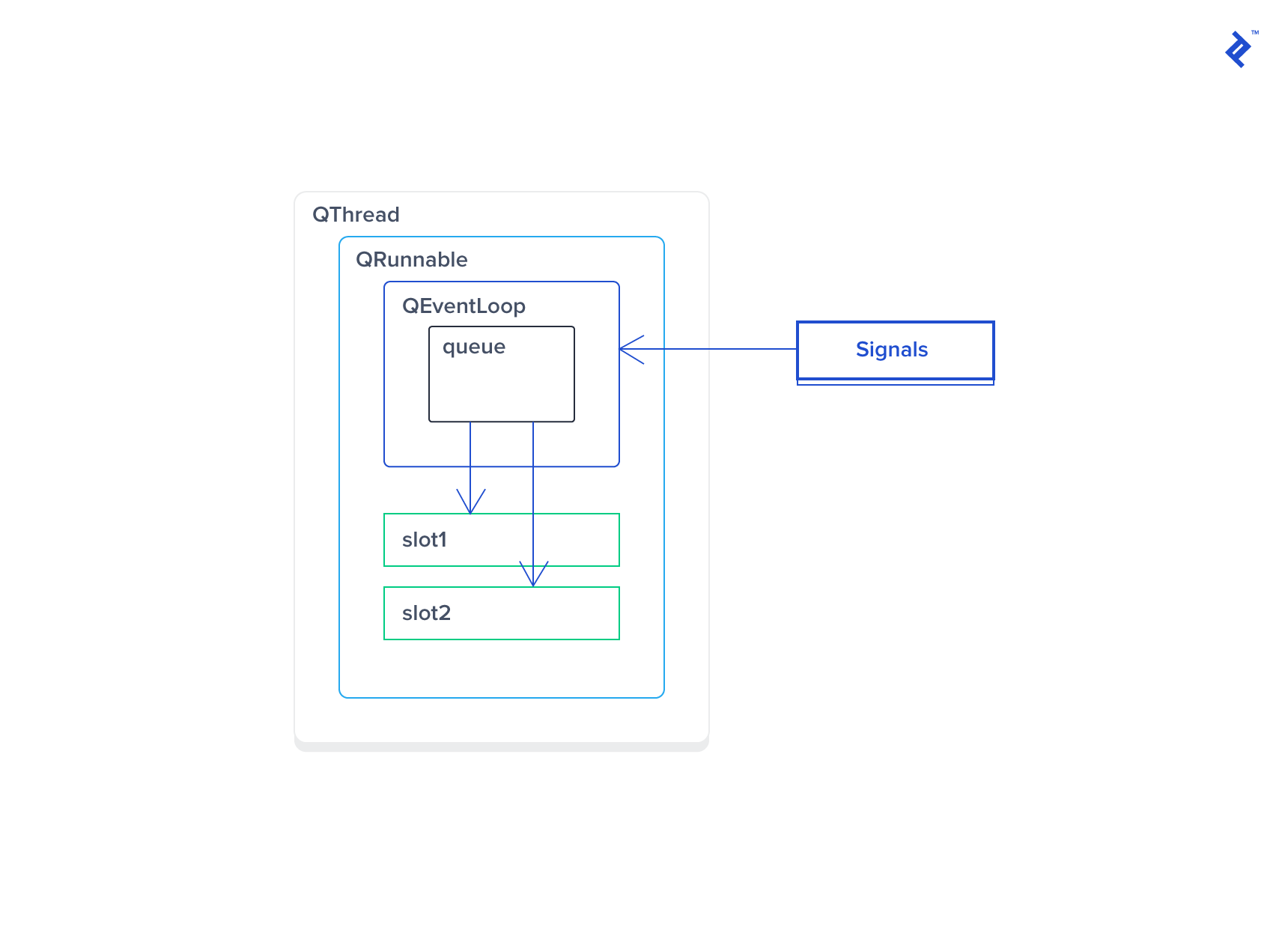

Qt’s flexibility allows circumventing the “missing event loop” issue by adding one to QRunnable:

| |

However, avoid such “workarounds” as they are risky and inefficient: if a thread pool thread (running MyTask) gets blocked waiting for a signal, it cannot execute other tasks from the pool.

Overriding QThread::run() allows running a QThread without an event loop. This is acceptable with proper understanding; for example, quit() won’t function as expected.

Running Single Task Instances Concurrently

Ensuring only one task instance executes at a time, with pending requests queued, is crucial when accessing exclusive resources like writing to a shared file or using TCP sockets.

Let’s temporarily set aside computer science and the producer-consumer pattern for a simple, common scenario.

A straightforward solution might involve using a QMutex. Acquiring the mutex within the task function effectively serializes threads, ensuring only one runs the function at a time. However, this impacts performance due to high contention, as threads block on the mutex before proceeding. Numerous threads actively using such a task while performing other work will spend most of their time idle.

| |

To mitigate contention, a queue and a dedicated worker thread are needed, reflecting the classic producer-consumer pattern. The worker (consumer) processes requests from the queue sequentially, while each producer adds requests to the queue. This might suggest using QQueue and QWaitCondition, but let’s explore achieving this without those primitives:

- Utilize

QThreadPoolwith its built-in task queue.

Or

- Leverage the default

QThread::run()with itsQEventLoop.

The first approach involves setting QThreadPool::setMaxThreadCount(1) and using QtConcurrent::run() for scheduling:

| |

This benefits from QThreadPool::clear(), enabling instant cancellation of pending requests, useful for swift application shutdowns. However, a significant drawback is thread-affinity: logEventCore likely executes in different threads between calls. Qt has classes requiring thread-affinity, including QTimer, QTcpSocket, and potentially others.

Qt documentation states that timers started in one thread cannot be stopped from another. Only the thread owning a socket can use it. Thus, timers must be stopped in their originating thread, and

QTcpSocket::close()must be called from the owning thread. These actions usually occur in destructors.

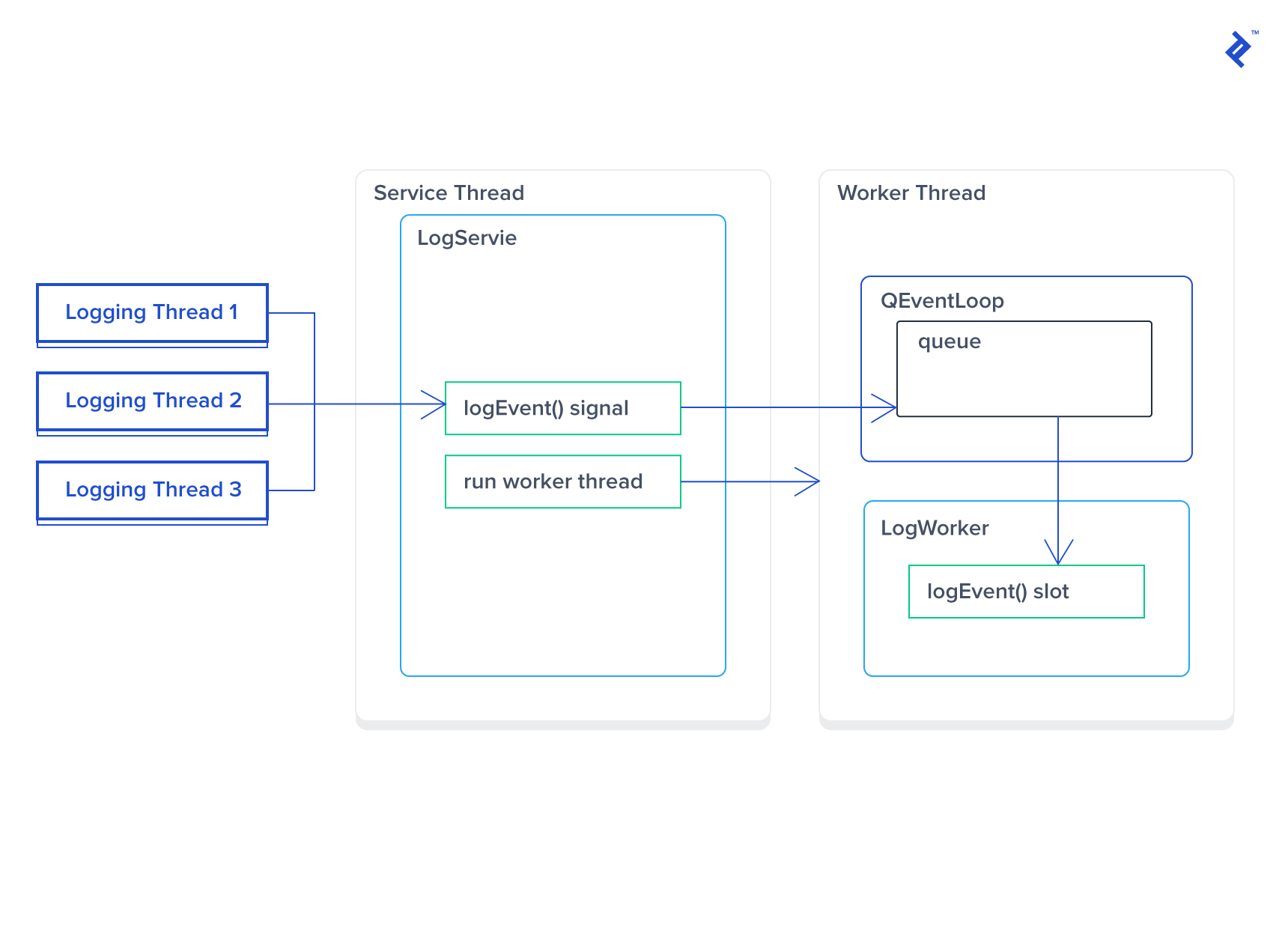

A better solution utilizes the QEventLoop provided by QThread. The concept involves using signals and slots for requests, with the thread’s event loop acting as a queue, processing one slot at a time.

| |

LogWorker’s constructor and logEvent implementations are straightforward and omitted here. A service is needed to manage the thread and worker instance:

| |

Here’s how this code functions:

- The constructor creates the thread and worker instance. The worker has no parent, as it’s moved to the new thread. Thus, Qt won’t automatically release the worker’s memory, requiring manual deletion by connecting

QThread::finishedtodeleteLater. The proxy methodLogService::logEvent()connects toLogWorker::logEvent()usingQt::QueuedConnectiondue to different threads. - The destructor queues the

quitevent in the event loop. This event is handled after all others. For instance, numerouslogEvent()calls before destruction are processed before the logger handles the quit event. This takes time, necessitatingwait()until the event loop exits. Logging requests posted after the quit event are never processed. - Logging (

LogWorker::logEvent) always occurs in the same thread, suitable for thread-affinity-requiring classes. TheLogWorkerconstructor and destructor execute in the main thread (whereLogServiceruns), demanding caution with code execution. Avoid stopping timers or using sockets in the worker’s destructor unless it runs in the same thread.

Executing Worker Destructors in the Same Thread

Workers dealing with timers or sockets require destructor execution in their dedicated thread. Subclassing QThread and deleting the worker within QThread::run() achieves this. Consider this template:

| |

Redefining the previous LogService example using this template:

| |

Here’s how it works:

LogServicebecomes theQThreadobject to implement the customrun()function. Private subclassing prevents accessingQThreadfunctions, allowing internal control over the thread’s lifecycle.Thread::run()runs the event loop via the defaultQThread::run()implementation, destroying the worker instance after the event loop exits. The worker’s destructor executes in the same thread.LogService::logEvent()acts as the proxy (signal) posting the logging event to the thread’s event queue.

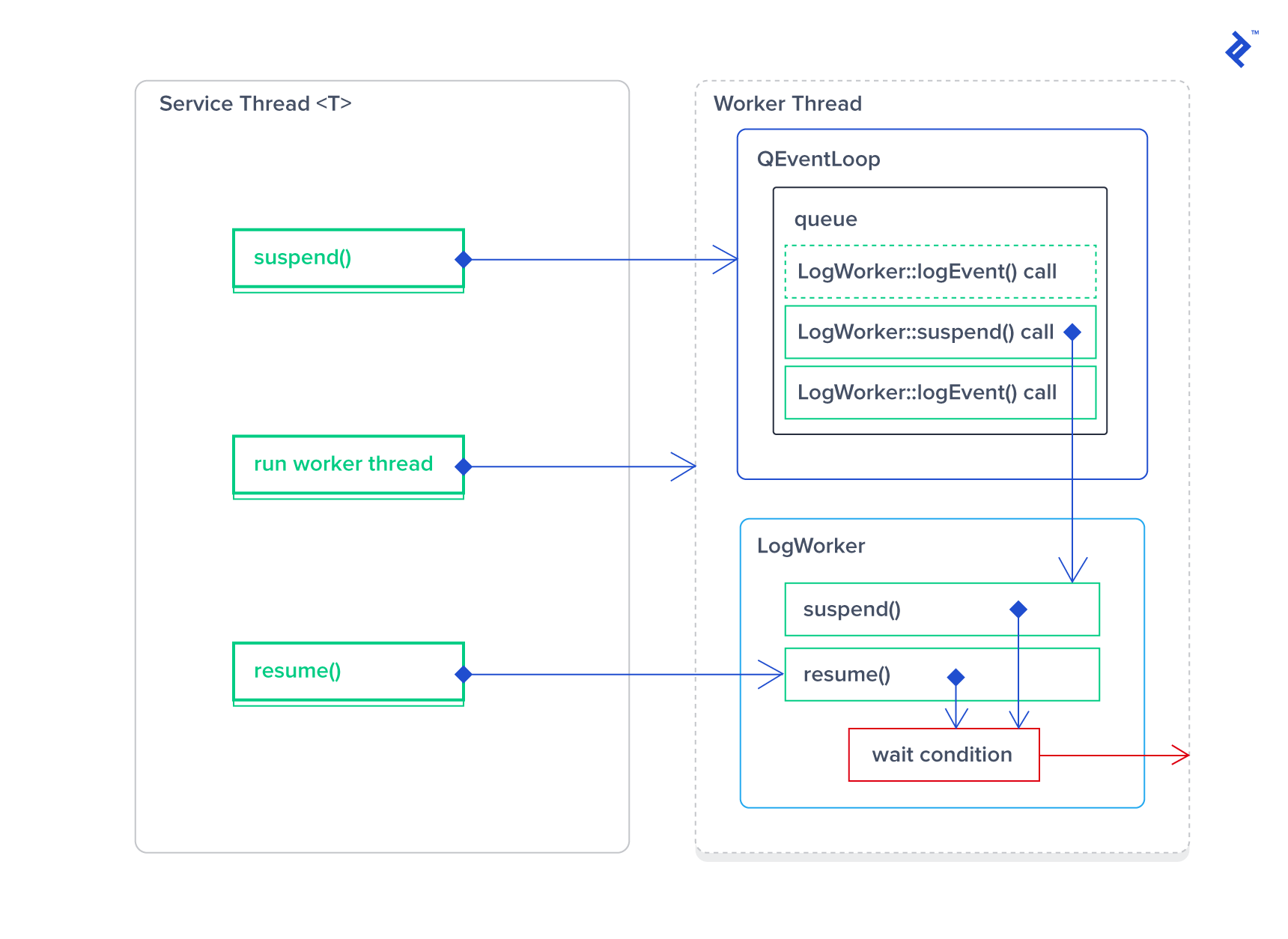

Pausing and Resuming Threads

Suspending and resuming custom threads is another useful capability. Imagine pausing processing when the application minimizes, locks, or loses network connectivity. Building a custom asynchronous queue for pending requests until worker resumption is possible. However, for simplicity, we’ll utilize the event loop’s queue for this purpose.

Suspending a thread requires waiting on a condition. While blocked, the event loop doesn’t process events, and Qt queues them. Upon resumption, the event loop handles accumulated requests. We’ll use a QWaitCondition object (requiring a QMutex) for the condition. For reusability, the suspend/resume logic goes into a base class called SuspendableWorker, supporting two methods:

suspend(): A blocking call setting the thread to wait on a condition. This involves posting a suspend request to the queue and waiting for its handling, similar toQThread::quit()followed bywait().resume(): Signals the wait condition to wake the thread for continued execution.

Interface and implementation review:

| |

| |

Suspended threads never receive quit events. Using this with standard QThread is unsafe unless resumed before posting “quit.” Let’s integrate this into our custom Thread<T> template for robustness.

| |

These changes ensure thread resumption before posting the quit event. Additionally, Thread<TWorker> accepts any worker type, whether a SuspendableWorker or not.

Usage example:

| |

volatile vs atomic

This is often misunderstood. Many assume volatile variables for flags accessed by multiple threads prevent data races, which is incorrect. QAtomic* classes (or std::atomic) are necessary for this.

Consider a TcpConnection class in a dedicated thread, requiring a thread-safe method: bool isConnected(). Internally, it listens for socket events (connected and disconnected) to maintain a boolean flag:

| |

Making _connected volatile doesn’t guarantee thread-safety for isConnected(). It might work most of the time but fail critically otherwise. Protecting variable access from multiple threads is crucial. Using QReadWriteLocker:

| |

This ensures reliability but isn’t as fast as lock-free atomic operations. The third solution offers speed and thread-safety (using std::atomic instead of QAtomicInt, but semantically equivalent):

| |

Conclusion

This article covered important concurrent programming concerns in Qt, designing solutions for specific use cases. Simple topics like atomic primitives, read-write locks, and others were omitted. If interested in these, leave a comment and request such a tutorial.

For those exploring Qmake, consider reading the recently published “The Vital Guide to Qmake.”