Navigating Situations Where a Testing Suite is Impractical

As developers, we sometimes face resource constraints that limit our ability to create both deliverables and accompanying automated tests. While forgoing tests might be feasible for small applications, this approach becomes unsustainable as projects grow in size and complexity. Manual testing becomes laborious and error-prone, often leading to regressions in areas untouched by recent code changes.

I’ve personally experienced the drawbacks of forgoing automated testing. Without it, I received client reports of unexpected application breakages, highlighting the importance of a robust testing strategy.

To address this, I started employing a simple yet effective technique: verifying basic website functionality by sending HTTP requests to each page, then parsing the response headers for the desired ‘200’ status code. This straightforward method, though seemingly basic, provides a degree of confidence in the application’s stability.

Demystifying Automated Testing

In web development, automated testing typically encompasses three main categories: unit tests, functional tests, and integration tests. These test types are often used in combination to ensure the smooth operation of the entire application. Running these tests together or in sequence, ideally with a single command or click, is what we refer to as automated testing.

The primary objective of these tests, especially in web development, is to ensure that all application pages render correctly, without encountering fatal errors or bugs.

Unit Testing Explained

Unit testing is a software development practice where the smallest testable components of code, known as units, are tested independently to verify their correct behavior. Here’s a Ruby example:

| |

Delving into Functional Testing

Functional testing assesses the features and functionality of a system or software application. It aims to cover all possible user interaction scenarios, including failure paths and boundary cases.

Note: all our examples are in Ruby.

| |

Understanding Integration Testing

After individual modules undergo unit testing, they are progressively integrated and tested together. This process, called integration testing, validates the combined behavior of these modules and ensures that the overall requirements are met.

| |

The Ideal World of Testing

Testing is a widely adopted practice in software development, and for good reason. Effective testing offers numerous advantages:

- It ensures the quality of the entire application with minimal manual effort.

- It simplifies bug identification by pinpointing the exact location of failures through test results.

- It facilitates automatic documentation generation for your code.

- It helps avoid ‘coding constipation’, a humorous term, according to a Stack Overflow user, that describes the feeling of being stuck when you’re unsure of what to code next.

While the benefits of testing are extensive, this overview highlights its conceptual significance.

Testing Realities

Despite the undeniable merits of all three testing types, they are often neglected in real-world projects due to various reasons:

Time Constraints and Deadlines

Deadlines are ever-present in software development, and dedicating time to write tests can impact timely project delivery. While some argue that testing ultimately saves time, the initial investment can be significant, particularly for those who prioritize rapid development.

Client-Related Challenges

Clients often lack a clear understanding of testing and its value in software development. They prioritize quick product launches and might perceive programmatic testing as a hindrance to rapid delivery. Budget constraints can also be a factor, as clients may be unwilling to allocate resources for testing efforts.

Knowledge Gaps

A significant number of developers are unfamiliar with testing methodologies. Many lack the knowledge and experience to write effective tests, understand what to test, or set up the necessary testing frameworks. Limited exposure to testing in academic settings and the perceived difficulty of learning these frameworks contribute to this knowledge gap.

The Perceived Burden of Testing

Writing tests can be overwhelming, even for seasoned programmers. It’s often viewed as unexciting and tedious compared to the thrill of implementing new features. This perception of testing as an unrewarding chore can discourage developers from embracing it.

Furthermore, writing tests can be inherently complex, and traditional computer science education often falls short in adequately preparing developers for this task. Refactoring code with unit tests can also be particularly challenging.

Differing Perspectives on Unit Testing

While unit testing is valuable for algorithmic logic, its effectiveness for coordinating dynamic code is debatable. Proponents argue that the initial time investment in writing tests pays off in the long run by reducing debugging and refactoring time. However, this assumes that the codebase remains static. In reality, successful software constantly evolves with new features, modifications, and removals, requiring ongoing test maintenance that can be time-consuming.

The Need for Some Form of Testing

The importance of testing, whether manual or automated, cannot be overstated. After implementing code changes, it’s crucial to verify that the application functions as expected. While many developers rely on manually testing basic functionalities like page rendering, form submission, and content display, this approach is inefficient, time-consuming, and prone to errors.

A Pragmatic Alternative: HTTP Request Testing

The core purpose of testing a web app is to ensure that pages render correctly in the user’s browser, free from fatal errors, and display the intended content. A simpler and often quicker way to achieve this is by sending HTTP requests to the application endpoints and analyzing the response. The response code indicates whether the page was successfully delivered, while parsing the response body allows for content verification by searching for specific text strings. For more sophisticated content checks, web scraping libraries like nokogiri can be employed.

For endpoints requiring user authentication, libraries like mechanize, designed for automating interactions (especially useful in integration tests), can simulate logins or click events. This approach, while resembling integration or functional testing in principle, offers faster implementation and easier integration into existing or new projects compared to setting up a full-fledged testing framework.

Testing large databases with diverse values poses a challenge, as ensuring application functionality across all potential datasets can be daunting. Manually anticipating and writing tests for every edge case is not only difficult but often impossible, leading to potentially hundreds of lines of code that are cumbersome to manage. HTTP requests offer a more efficient solution, allowing for direct testing of these edge cases using production data downloaded locally or on a staging server.

While this technique is not a universal remedy and has its limitations, it provides a faster and simpler approach to writing and modifying tests, especially when traditional testing methods are not feasible.

Practical Application: Testing with HTTP Requests

Given that neglecting testing altogether is not advisable, a basic yet effective approach is to send HTTP requests to all application pages locally and check for the desired ‘200’ status code in the response headers.

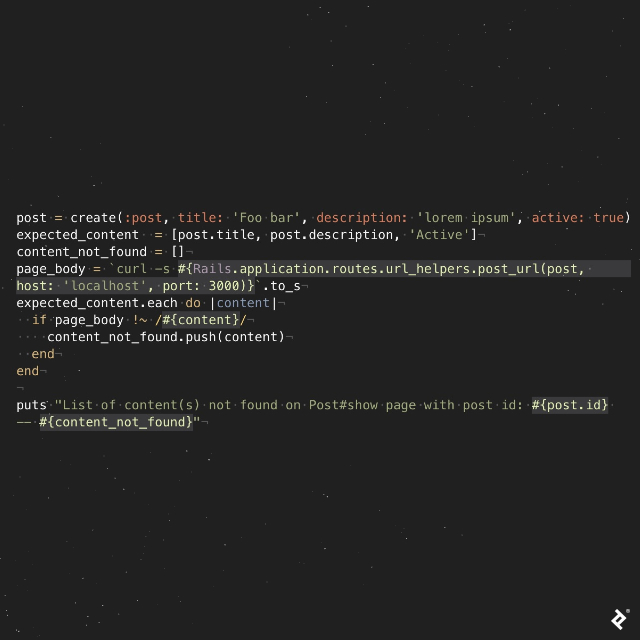

For instance, the content and fatal error tests mentioned earlier can be implemented using HTTP requests in Ruby as follows:

| |

This single line of code (curl -X #{route[:method]} -s -o /dev/null -w "%{http_code}" #{Rails.application.routes.url_helpers.articles_url(host: 'localhost', port: 3000) }) effectively covers numerous test cases, as any error raised on the article’s page would be detected, replacing hundreds of lines of potential unit tests.

The second part, responsible for catching content errors, can be reused to verify content across multiple pages. While more complex requests can be handled using libraries like mechanize, this example demonstrates the basic principle.

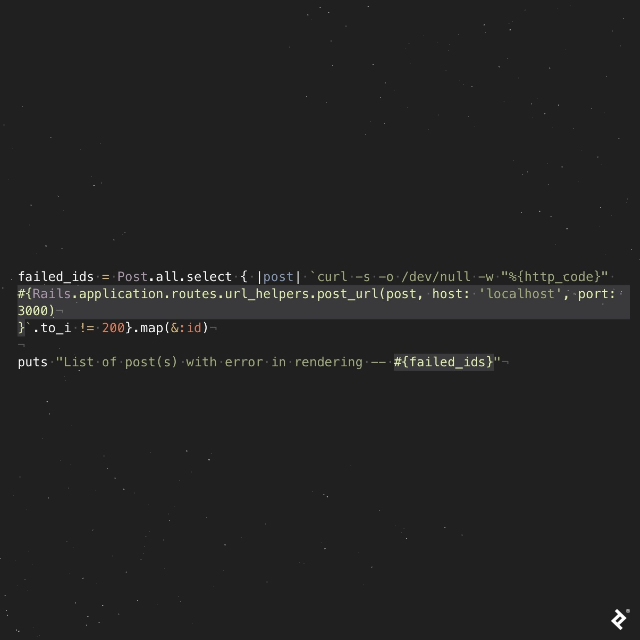

Testing page functionality against a large and varied dataset, such as verifying an article page template against all articles in a production database, can be achieved as follows:

| |

This code snippet retrieves an array of IDs for articles that failed to render, allowing you to investigate the issue on the specific article pages.

It’s important to acknowledge that this method might not be suitable for all scenarios, such as testing standalone scripts or email functionality. Moreover, it’s inherently slower than unit tests due to the direct endpoint calls for each test. However, when traditional testing methods like unit or functional testing are not viable, HTTP request testing offers a valuable alternative.

For small, straightforward projects, tests can reside in a single file executed before each commit. However, larger projects necessitate a more structured testing suite. A recommended approach is to organize tests within the regular test folder, with each major endpoint assigned its dedicated file (e.g., in Rails, each model/controller could have its own test file). This file can be further divided based on the testing aspects, commonly consisting of at least three sections:

Test One: Verifying Error-Free Page Rendering

This code snippet demonstrates iterating through a list of endpoints for “Post” to confirm that each page renders without errors. A successful test run would output something similar to: ➜ sample_app git:(master) ✗ ruby test/http_request/post_test.rb List of failed url(s) -- []

Any rendering errors would be reported like this (in this instance, the posts/index page failed to render): ➜ sample_app git:(master) ✗ ruby test/http_request/post_test.rb List of failed url(s) -- [{:url=>”posts_url”, :params=>[], :method=>”GET”, :http_code=>”500”}]

Test Two: Content Verification

This section ensures that all expected content is present on the page. A successful test would result in: ➜ sample_app git:(master) ✗ ruby test/http_request/post_test.rb List of content(s) not found on Post#show page with post id: 1 -- []

If any expected content is missing, the output would indicate the missing element, like so: ➜ sample_app git:(master) ✗ ruby test/http_request/post_test.rb List of content(s) not found on Post#show page with post id: 1 -- [“Active”] (in this case, the post status “Active” is expected but not found).

Test Three: Dataset-Specific Rendering

This final test checks if the page renders correctly across different datasets. If all pages render without errors, the output would be an empty list: ➜ sample_app git:(master) ✗ ruby test/http_request/post_test.rb List of post(s) with error in rendering -- []

However, any rendering issues related to specific records would be reported, as shown here: ➜ sample_app git:(master) ✗ ruby test/http_request/post_test.rb List of post(s) with error on rendering -- [2,5] (indicating problems with records having IDs 2 and 5).

For those interested in experimenting with this code, here’s my github project.

Choosing the Right Approach: HTTP Request Testing vs. Traditional Testing

HTTP request testing might be more suitable when:

- The project involves a web application.

- Time constraints necessitate a quick testing solution.

- The project is large, pre-existing, lacks tests, but requires code verification.

- The code primarily involves simple requests and responses.

- Minimizing test maintenance effort is a priority.

- Testing application functionality across all values in an existing database is crucial.

Traditional testing methods are generally preferred when:

- The project involves non-web applications, such as scripts.

- The code is complex and algorithmic.

- Sufficient time and budget are available for thorough testing.

- The business requires near-perfect software reliability with minimal errors (e.g., financial applications, large user bases).

In conclusion, while traditional testing methods remain relevant, this article provides an alternative approach using HTTP request testing. This method offers a practical solution when time constraints or project complexities make traditional testing less feasible, ensuring a degree of code confidence and stability.