Many homes have air conditioning systems that lack modern features such as central automation, programmable thermostats, multiple sensors, or Wi-Fi control. Although this older technology remains dependable, upgrades are often postponed.

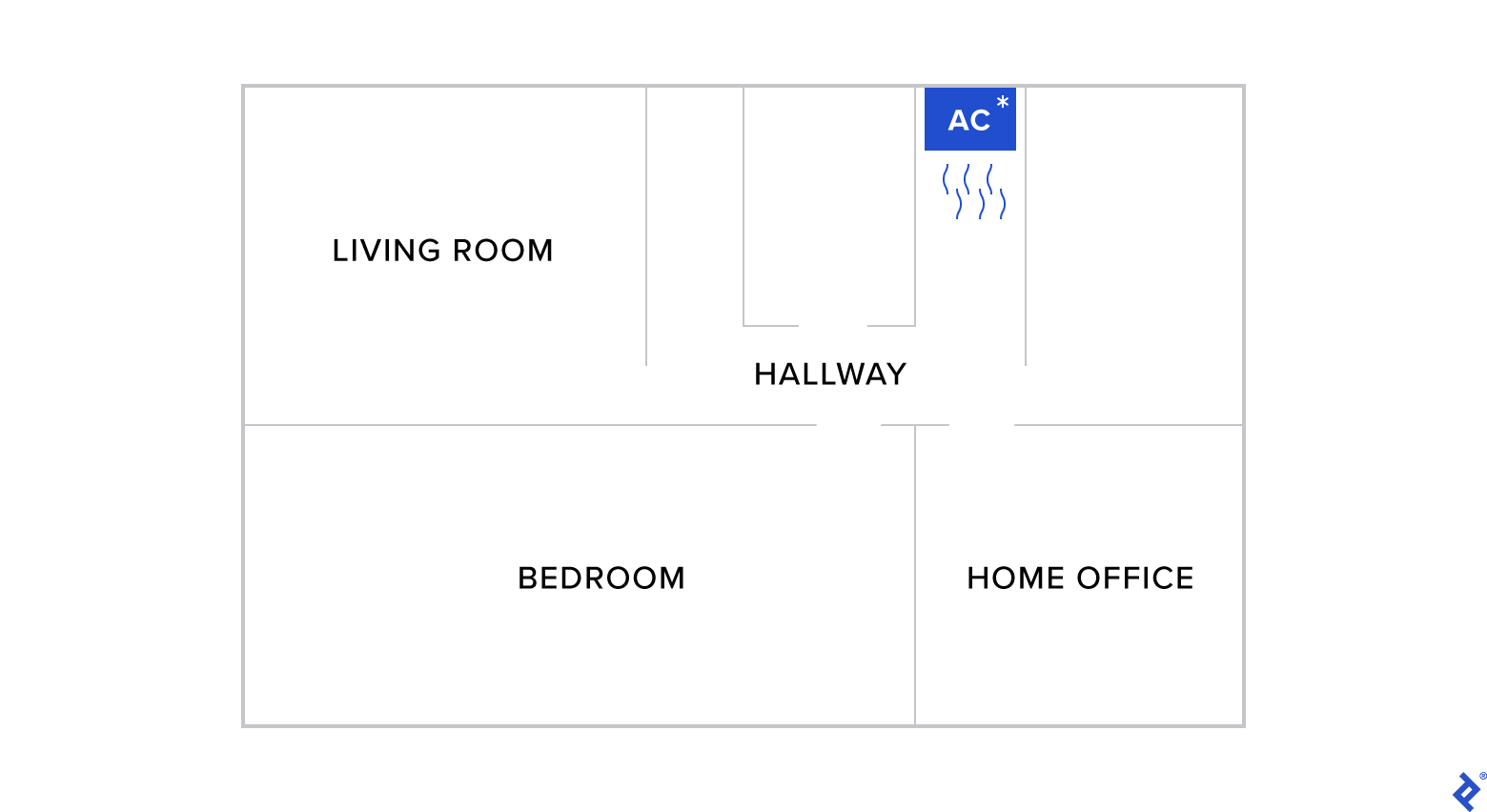

However, this situation frequently requires users to manually switch the air conditioner on or off, disrupting their work or sleep. This is particularly noticeable in homes with compact designs, similar to my own:

While central air conditioning is prevalent in US households, it’s not a global standard. The absence of central AC limits automation possibilities, making it challenging to maintain a consistent temperature throughout the entire house. This limitation particularly hinders efforts to prevent temperature variations that might necessitate manual adjustments.

My interest in the Internet of Things (IoT) and engineering background presented an opportunity to achieve multiple objectives concurrently:

- Enhance energy conservation by optimizing the efficiency of my standalone air-conditioning unit

- Elevate home comfort through automation and seamless Google Home integration

- Develop a tailored solution exceeding the limitations of commercially available options

- Refresh my professional expertise by employing reliable hardware

My air conditioner is a standard model operated by a simple infrared remote control. Although I was familiar with devices like Sensibo or Tado, which enable smart home system integration for air conditioning units, I decided on a DIY approach. I built a Raspberry Pi thermostat, aiming for advanced control based on sensor data gathered from multiple rooms.

Constructing a Raspberry Pi Thermostat

I was already utilizing several Raspberry Pi Zero Ws, paired with DHT22 sensor modules, to keep track of temperature and humidity levels in various rooms. Due to my home’s segmented layout, I strategically placed these sensors to accurately gauge the temperature in different sections.

Additionally, I have a home surveillance system (not essential for this project) set up on a Windows 10 PC using WSL 2. My goal was to integrate the sensor readings into the surveillance videos as a text overlay on the live feed.

Wiring the Sensor

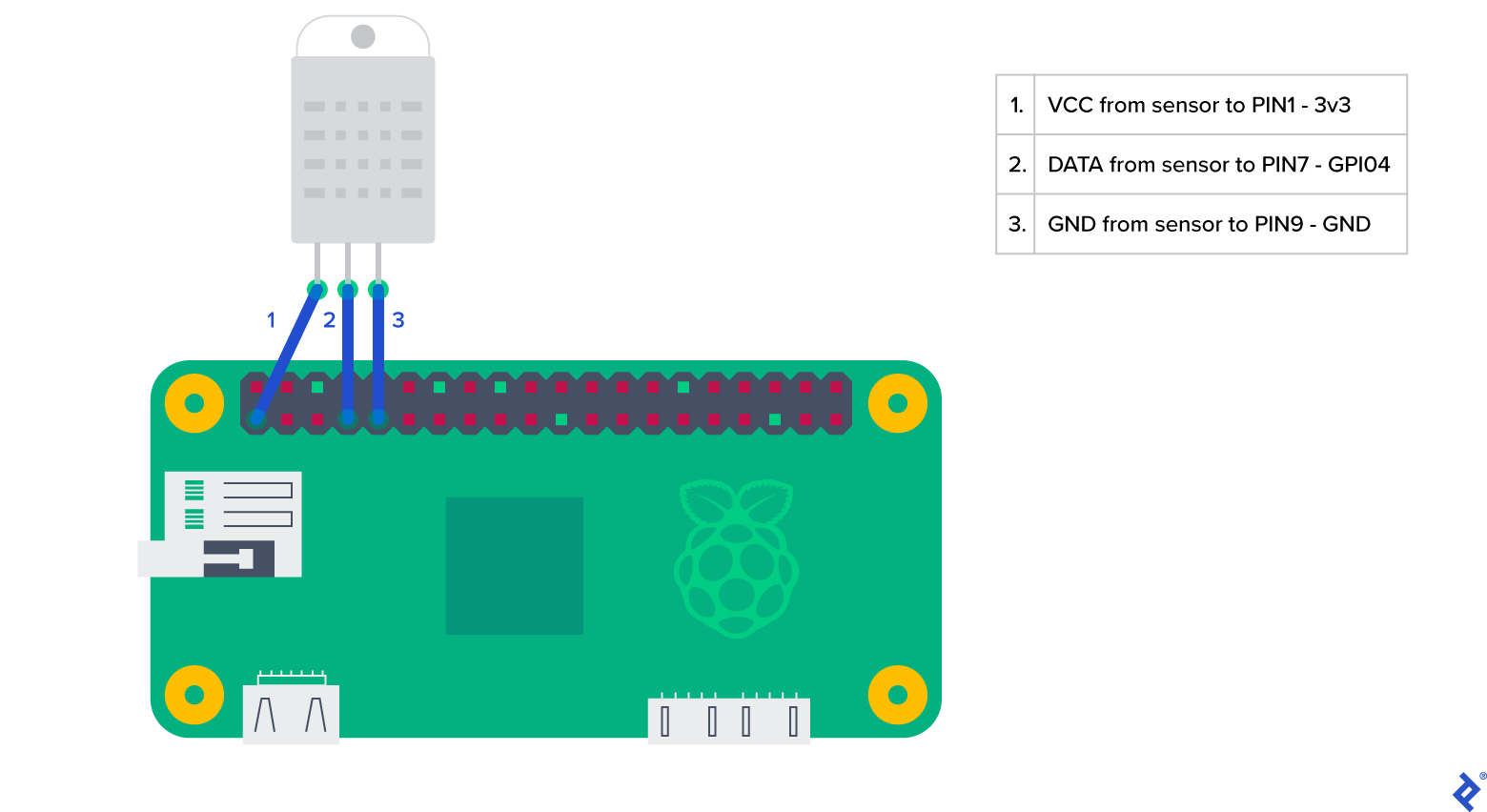

Wiring the sensors was simple, involving only three connections:

I opted for Raspberry Pi OS Lite, where I installed Python 3 with PiP along with the Adafruit_DHT library for Python to collect data from the sensor. Although technically outdated, it’s easier to set up, uses fewer resources, and is sufficient for this purpose.

To maintain a record of all readings, I decided to employ a third-party server, ThingSpeak, for hosting the data and accessing it through API calls. This approach is relatively straightforward, and since I didn’t require real-time updates, transmitting data every five minutes was adequate.

| |

On my dedicated surveillance PC running WSL 2, I implemented a PHP script to retrieve data from ThingSpeak, format it, and write it to a simple .txt file. My surveillance software uses this .txt file to superimpose the data onto the video stream.

Given the existing home automation elements, including smart bulbs and various Google Home routines, it seemed logical to utilize the sensor data to create a smart thermostat within Google Home. The plan was to develop a Google Home routine that would automatically activate or deactivate the air conditioner based on room temperature, eliminating the need for user intervention.

While more expensive all-inclusive options like Sensibo and Tado simplify the technical setup, the PNI SafeHome PT11IR presented a budget-friendly alternative, enabling me to control multiple infrared devices within range using my phone. Conveniently, the control app, Tuya, seamlessly integrates with Google Home.

Resolving Google Home Integration Challenges

With a smart-enabled air conditioner and readily available sensor data, I attempted to integrate the Raspberry Pi as a thermostat in Google Home, but without success. Although I could transmit sensor readings to Google IoT Cloud and its Pub/Sub service, relaying this data to Google Home for routine creation proved impossible.

After several days of contemplation, I devised a new strategy. What if instead of sending data to Google Home, I could locally analyze it and then issue commands to Google Home to switch the air conditioner on or off? Encouraged by successful tests with voice commands, I pursued this approach.

A quick search led me to Assistant Relay, a Node.js-based system that empowers users to send commands to Google Assistant. This means you can connect virtually anything to Google Assistant, as long as it can interpret and act upon the received input.

Impressively, Assistant Relay allowed me to send commands to my Google Assistant by simply transmitting POST requests, containing specific parameters, to the device running the Node.js server (in this case, my Raspberry Pi Zero W). It’s remarkably straightforward, and the script is well documented, so I’ll refrain from delving into excessive detail here.

Since the sensor data was already being processed on the surveillance PC, I decided to integrate the request into the PHP script, consolidating functionalities in a central location.

You can simplify the process, as you likely don’t require the .txt file, by directly reading sensor data and issuing commands based on it to the Google Assistant Service via Assistant Relay. All of this can be accomplished on a single Raspberry Pi without extra hardware. However, having already completed half the work, leveraging my existing setup made more sense. Both scripts in this article are compatible with a single machine, and if needed, the PHP script can be rewritten in Python.

Establishing Conditions and Automating Operations

My goal was to limit automatic power cycling to nighttime hours, specifically between 10 PM and 7 AM. After defining this operational timeframe, I established a preferred temperature range. Finding the ideal temperature intervals that ensured comfort without straining the air conditioner through frequent power cycles involved some trial and error.

The PHP script generating the sensor data overlay was configured to run every five minutes via a cron job. Therefore, the only additions required were the conditions and the POST request.

However, this presented a problem. If the conditions were met, the script would send a “turn on” command every five minutes, even if the air conditioner was already running. This resulted in an irritating beeping sound from the unit, even for the “turn off” command. To address this, I needed a method to determine the unit’s current state.

Elegance wasn’t a priority, so I created a JSON file containing an array. Upon successful execution of the “turn on” or “turn off” commands, the script would append the latest status to this array. This resolved the redundancy issue. However, exceptionally hot days or excessive heating during winter could still trigger the conditions. A manual override seemed sufficient for such situations. I’ll leave the implementation of a return statement before the switch snippet for this purpose as an exercise for the reader:

| |

While the solution works, it wasn’t without its initial hiccups. Adjustments and tweaks were necessary along the way. Hopefully, armed with my experience, you’ll encounter fewer obstacles in achieving a successful implementation on your first attempt.

The Value of a Raspberry Pi Thermostat Controller

The unconventional layout of my home, leading to significant temperature variations between rooms, was the driving force behind automating my air conditioning. However, the benefits of automating heating and cooling extend beyond this specific issue.

Globally, people live in diverse climates and face varying energy costs, with different rates throughout the day. As a result, even minor enhancements in energy efficiency can make automation financially viable in certain regions.

Moreover, the increasing prevalence of home automation highlights the potential of automating older, energy-intensive devices like air conditioners, electric heaters, and water heaters. These appliances are typically bulky, challenging to install, and costly to upgrade, leading many people to retain them for extended periods. By adding a layer of intelligence to these “dumb” devices, we can not only enhance comfort and energy efficiency but also potentially prolong their lifespan.

- How to repurpose your old smartphone as a remote control