In today’s development world, choosing the right framework is crucial when starting a new project. Building a complex web application without one is almost unthinkable.

While some languages have a go-to framework, like Ruby with Ruby on Rails and Python with Django, PHP offers a variety of popular options. According to Google trends and GitHub, the leading PHP frameworks at the time of this article are Symfony with 13.7k stars and Laravel with 29k stars.

This article compares these two frameworks by demonstrating how to implement common features using each. This side-by-side comparison of real-world examples will help you make an informed decision.

A strong understanding of PHP and the MVC architecture is assumed, but prior experience with Symfony or Laravel is not necessary.

Laravel vs. Symfony: A Closer Look

Laravel

Laravel, specifically version 4 and later, is the focus here. Laravel 4, released in 2013, was a complete overhaul of the framework. It embraced a modular design, utilizing Composer to manage its decoupled components, a departure from the previous monolithic approach.

Marketed as a framework for rapid development, Laravel boasts a clean and elegant syntax that is easy to learn, understand, and maintain. Its popularity is undeniable, being the most popular framework in 2016. Data from Google trends shows it to be three times more popular than other frameworks, and on GitHub, it enjoys twice as many stars as its competitors.

Symfony

Symfony 2, launched in 2011, marked a significant departure from its predecessor, Symfony 1, with a completely different architecture and philosophy. Created by Fabien Potencier, Symfony is currently at version 3.2, an incremental update to Symfony 2. Hence, they are often collectively referred to as Symfony2/3.

Similar to Laravel 4, Symfony 2 is designed with decoupled components. This offers two main advantages: the flexibility to replace any component within a Symfony project and the ability to reuse individual components in non-Symfony projects. Symfony components, serving as excellent code examples, are used in various open-source projects](http://symfony.com/projects), including Drupal, phpBB, and Codeception. Laravel itself leverages no fewer than 14 Symfony components. Therefore, familiarity with Symfony can be beneficial when working with other projects.

Framework Installation

Both frameworks offer installers and wrappers accessible via the PHP built-in web server.

Symfony Installation

Installing Symfony is straightforward:

| |

That’s all it takes! Your Symfony installation is accessible at the URL http://localhost:8000.

Laravel Installation

Installing Laravel is equally simple, mirroring the process for Symfony. The only difference is that Laravel’s installer is obtained through Composer:

| |

You can then access http://localhost:8000 to verify your Laravel installation.

Note: Both Laravel and Symfony, by default, use the same localhost port (8000). This means you can’t run their default instances simultaneously. Remember to stop the Symfony server using php bin/console server:stop before starting the Laravel server.

Beyond Basic Installation

While these are basic installation examples, both frameworks provide Vagrant boxes for more advanced setups, such as configuring projects with local domains or running multiple projects concurrently:

Essential Framework Configurations

Symfony’s Approach to Configuration

Symfony utilizes YAML for its configuration syntax. The main configuration file, app/config/config.yml, resides in the app/config directory. A basic example is shown below:

| |

To create environment-specific configurations, use the file app/config/config_ENV.yml, populating it with the relevant configuration parameters. Here’s an example of a config_dev.yml file for the development environment:

| |

This example activates the web_profiler, a Symfony tool, exclusively for the development environment. This tool facilitates debugging and profiling your application directly within the browser.

You might have noticed %secret% constructs in the configuration files. These allow environment-specific variables to be stored in a separate parameters.yml file. This file, unique to each machine, is not tracked by version control. Instead, a template file, parameters.yml.dist, is used for version control and serves as the blueprint for the parameters.yml file.

Below is an example of the parameters.yml file:

| |

Laravel’s Configuration Approach

Laravel’s configuration differs significantly from Symfony’s. The only commonality is the use of a file not tracked by version control (.env in Laravel) and a template for generating this file (.env.example). This file contains a list of key-value pairs, as illustrated below:

| |

Like Symfony’s YAML file, Laravel’s configuration file is human-readable and well-structured. Additionally, you can create a .env.testing file specifically for running PHPUnit tests.

Application configuration in Laravel is managed through .php files within the config directory. Basic settings are stored in app.php, while component-specific configurations are placed in <component>.php files (e.g., cache.php or mail.php). Here’s an example of a config/app.php file:

| |

Comparing Configuration: Symfony vs. Laravel

Symfony’s approach to application configuration allows for environment-specific configuration files and prevents complex PHP logic from being embedded within the YAML configuration.

However, Laravel’s use of the familiar PHP syntax for configuration might be more appealing, eliminating the need to learn YAML syntax.

Routing and Controller: The Essentials

At its core, a back-end web application primarily handles requests and generates responses based on the request content. The controller acts as the intermediary, transforming requests into responses by invoking application methods. The router, on the other hand, determines which controller class and method should handle a specific request.

Let’s illustrate this by creating a controller that displays a blog post page requested from the /posts/{id} route.

Laravel’s Implementation of Routing and Controller

Controller

| |

Router

| |

We’ve defined the route for GET requests. Any request matching the /posts/{id} URI will trigger the show method of the BlogController and pass the id parameter to it. The controller attempts to retrieve the POST model object associated with the provided id and utilizes the Laravel helper view() to render the page.

Symfony’s Approach to Routing and Controller

In Symfony, the exampleController is a bit more involved:

| |

As the @Route("/posts/{id}”) annotation is already included, we only need to define the controller in the routing.yml configuration file:

| |

The step-by-step logic mirrors that of Laravel’s implementation.

Comparing Routing and Controller: Symfony vs. Laravel

At first glance, Laravel might appear more appealing due to its initial simplicity and ease of use. However, in real-world applications, it’s not advisable to directly invoke Doctrine from the controller. Instead, a service should be called to attempt to retrieve the post or throw an HTTP 404 Exception.

Templates: Shaping the View

Laravel utilizes the Blade template engine, while Symfony employs Twig. Both engines offer two key features:

- Template inheritance

- Blocks or sections

These features allow for the definition of base templates with overridable sections and child templates that populate these sections with content.

Let’s revisit the blog post page example to illustrate this.

Laravel Blade: The Template Engine

| |

You can then instruct Laravel in your Controller to render the post.blade.php template. Recall the view(‘post’, …) call in the previous Controller example? The code doesn’t need to be aware of any template inheritance. This is all handled within the templates, at the view level.

Symfony Twig: The Template Engine in Action

| |

Comparing Templates: Symfony vs. Laravel

Structurally, Blade and Twig share many similarities. Both compile templates into PHP code for fast execution and support control structures like if statements and loops. Importantly, both engines escape output by default, enhancing security against XSS attacks.

Syntax aside, the key difference lies in Blade’s allowance of direct PHP code injection within templates, which Twig prohibits. Instead, Twig relies on filters.

For instance, to capitalize a string in Blade:

| |

In contrast, Twig would achieve this with:

| |

While Blade simplifies extending functionality, Twig enforces a strict separation between templates and PHP code.

Dependency Injection: Managing Dependencies

Applications often comprise numerous services and components with varying dependencies. Managing these dependencies and the information about created objects requires a dedicated mechanism.

This is where Service Container comes in. It is a PHP object responsible for creating requested services and storing information about the created objects and their dependencies.

Consider this scenario: You’re creating a PostService class with a method for creating new blog posts. This class depends on two other services: PostRepository, responsible for database interactions, and SubscriberNotifier, which handles notifications to subscribed users about new posts. To function correctly, PostService needs these two services injected as constructor arguments.

Dependency Injection in Symfony: An Example

First, let’s define our example services:

| |

| |

| |

Next, we configure dependency injection:

| |

You can now request the PostService from your Service Container object anywhere in your code, such as within a controller:

| |

The Service Container is a valuable component that encourages adherence to SOLID design principles when building applications.

Dependency Injection in Laravel: A Simpler Approach

Laravel simplifies dependency management considerably. Let’s revisit the same example:

| |

| |

| |

Here’s the beauty of Laravel – no need for manual dependency configurations. Laravel automatically analyzes the constructor argument types of PostService and resolves the dependencies.

You can also leverage injection directly in your controller methods by type-hinting PostService in the method arguments:

| |

Comparing Dependency Injection: Symfony vs. Laravel

Laravel’s autodetection mechanism excels in simplicity. Symfony offers a similar feature called “autowire,” but it’s disabled by default and requires some configuration by adding autowire: true to your dependency configuration. Laravel’s approach is undoubtedly more straightforward.

Object-Relational Mapping (ORM): Bridging the Gap

Both frameworks provide ORM capabilities for database interactions. ORM maps database records to objects in the code. This involves creating models representing each record type (or table) in your database.

Symfony relies on the third-party project Doctrine for database interactions, whereas Laravel uses its own library, Eloquent.

Eloquent ORM implements the ActiveRecord pattern pattern for database operations. In this pattern, each model is database-aware and can interact with it directly, performing actions like saving, updating, and deleting records.

Doctrine, on the other hand, implements the Data Mapper pattern pattern. Here, models are oblivious to the database and only concerned with the data itself. A separate layer, the EntityManager, manages the interaction between models and the database, handling all operations.

Let’s use an example to highlight the differences. Assume your model has a primary id key, title, content, and author. The Posts table only stores the author’s id, requiring a relation to the Users table.

Doctrine: The Data Mapper in Action

First, we define the models:

| |

| |

With the model mapping information in place, we can use a helper to generate method stubs:

| |

Next, we define methods for the post repository:

| |

Now, these methods can be called from services or, for example, from the PostController:

| |

Eloquent: The Active Record Approach

Laravel ships with a default User model, so we only need to define the Post model:

| |

That’s all for the models. Eloquent dynamically generates model properties based on the database table structure, eliminating the need for manual definition. To store a new post $post in the database, you’d use the following call (e.g., from the controller):

| |

To retrieve all posts by an author with a specific name, the optimal approach would be to first find the user by name and then request all the user’s posts:

| |

Comparing ORM: Symfony vs. Laravel

When it comes to ORM, Eloquent’s Active Record pattern is arguably more intuitive for PHP developers and easier to grasp than Doctrine’s Data Mapper approach.

Event Dispatcher vs. Middleware: Handling Application Flow

Understanding a framework’s lifecycle is essential.

Symfony’s Event Dispatcher: A Chain of Events

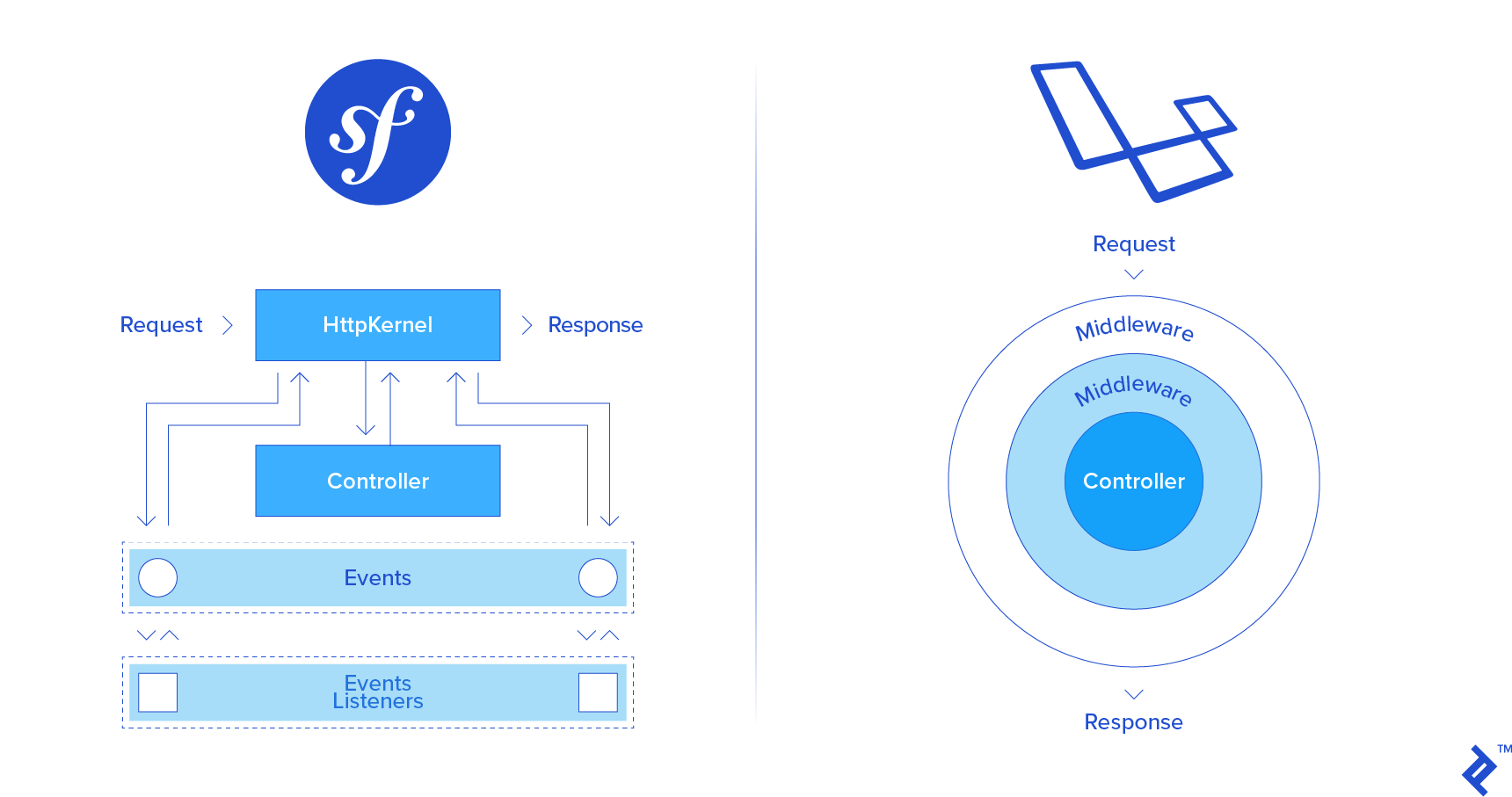

Symfony employs the EventDispatcher to process requests and generate responses. It sequentially triggers various lifecycle events, each handled by specific event listeners. Initially, the kernel.request event, containing request information, is dispatched. The primary listener for this event is the RouterListener, which invokes the router component to determine the appropriate route rule. Subsequently, other events are executed step by step. Common event listeners include Security checks, CSRF token verification, and logging processes. To add custom functionality within the request lifecycle, you create a custom EventListener and subscribe it to the relevant event.

Laravel’s Middleware: Layers of Processing

Laravel takes a different approach, utilizing middleware. Middleware can be visualized as layers surrounding your application. Requests pass through these layers on their way to the controller and back. Therefore, adding functionality to the request lifecycle involves introducing a new layer to the middleware stack, which Laravel will execute.

REST API: Building an API

Let’s create a basic CRUD example for managing blog posts:

- Create -

POST /posts/ - Read -

GET /posts/{id} - Update -

PATCH /posts/{id} - Delete -

DELETE /posts/{id}

Symfony and REST APIs: Leveraging Bundles

Symfony doesn’t offer a built-in solution for rapid REST API development but benefits from excellent third-party bundles like FOSRestBundle and JMSSerializerBundle.

Let’s look at a minimal working example using FOSRestBundle and JMSSerializerBundle. After installation and activation in AppKernel, configure the bundles to use JSON format and to omit it from URL requests:

| |

In the routing configuration, specify that the controller will implement a REST resource:

| |

We previously implemented a persist method in the repository. Now, let’s add a delete method:

| |

Next, we need to create a form class to handle input requests and map them to the model. This can be done using a CLI helper:

| |

This will generate a form type with the following code:

| |

Now, let’s implement the controller.

Note: The following code prioritizes demonstrating each method step-by-step and might not adhere to all design principles. However, it can be easily refactored.

| |

With FOSRestBundle, there’s no need to define routes for each method. Simply follow the naming conventions for controller methods, and JMSSerializerBundle will automatically handle the conversion of models to JSON.

Laravel and REST APIs: A Simpler Approach

First, define the routes. This can be done in the API section of the route rules (located in routes/api.php) to disable certain default middleware components and enable others.

| |

In the model, define the $fillable property to control which variables can be mass-assigned during model creation and updates:

| |

Now, let’s define the controller:

| |

Unlike Symfony’s FosRestBundle, which automatically wraps errors in JSON, Laravel requires manual handling. Update the render method in the Exception handler to return JSON errors when JSON requests are expected:

| |

Comparing REST APIs: Symfony vs. Laravel

For typical REST API development, Laravel’s approach is notably simpler than Symfony’s.

Choosing a Winner: Symfony or Laravel?

There’s no definitive winner between Laravel and Symfony. The best choice depends entirely on your project’s specific requirements and your priorities. It’s worth noting that several alternatives to Laravel and Symfony have emerged over the years, but they are outside the scope of this comparison.

Choose Laravel if:

- You’re new to frameworks, as it’s easy to learn, has a simpler syntax, and offers better learning resources.

- You’re building a startup product and testing hypotheses, as it’s well-suited for rapid application development, and Laravel developers are readily available.

Symfony is the better option if:

- You’re developing a complex enterprise application, as it’s highly scalable, maintainable, and well-structured.

- You’re migrating a large, long-term project, as Symfony provides predictable release plans for the next six years, minimizing the risk of unexpected changes.