Editor’s note: This article was updated on 10/25/22 by our editorial team. It has been modified to include recent sources and to align with our current editorial standards.

React is designed to build interactive user interfaces that are declarative, modular, and cross-platform. Today, it’s a leading JavaScript framework, possibly the most popular, for developing high-performance front-end applications. While initially intended for Single Page Applications (SPAs), React now powers entire websites and mobile apps. However, its strengths also present challenges for SEO.

Developers familiar with traditional web development transitioning to React will find themselves shifting significant portions of HTML and CSS code into JavaScript. This is because React favors describing the desired UI “state” over direct manipulation of UI elements. React then efficiently updates the DOM to reflect this state.

Consequently, all UI or DOM modifications happen through React’s engine. While convenient for developers, this can result in longer user load times and make it harder for search engines to discover and index content, potentially hurting the SEO of React webpages.

This article delves into the difficulties of creating SEO-friendly React apps and websites, and provides solutions to overcome them.

Google’s Webpage Crawling and Indexing Process

With a dominant share of over 90% of online searches, understanding Google’s crawling and indexing process is crucial.

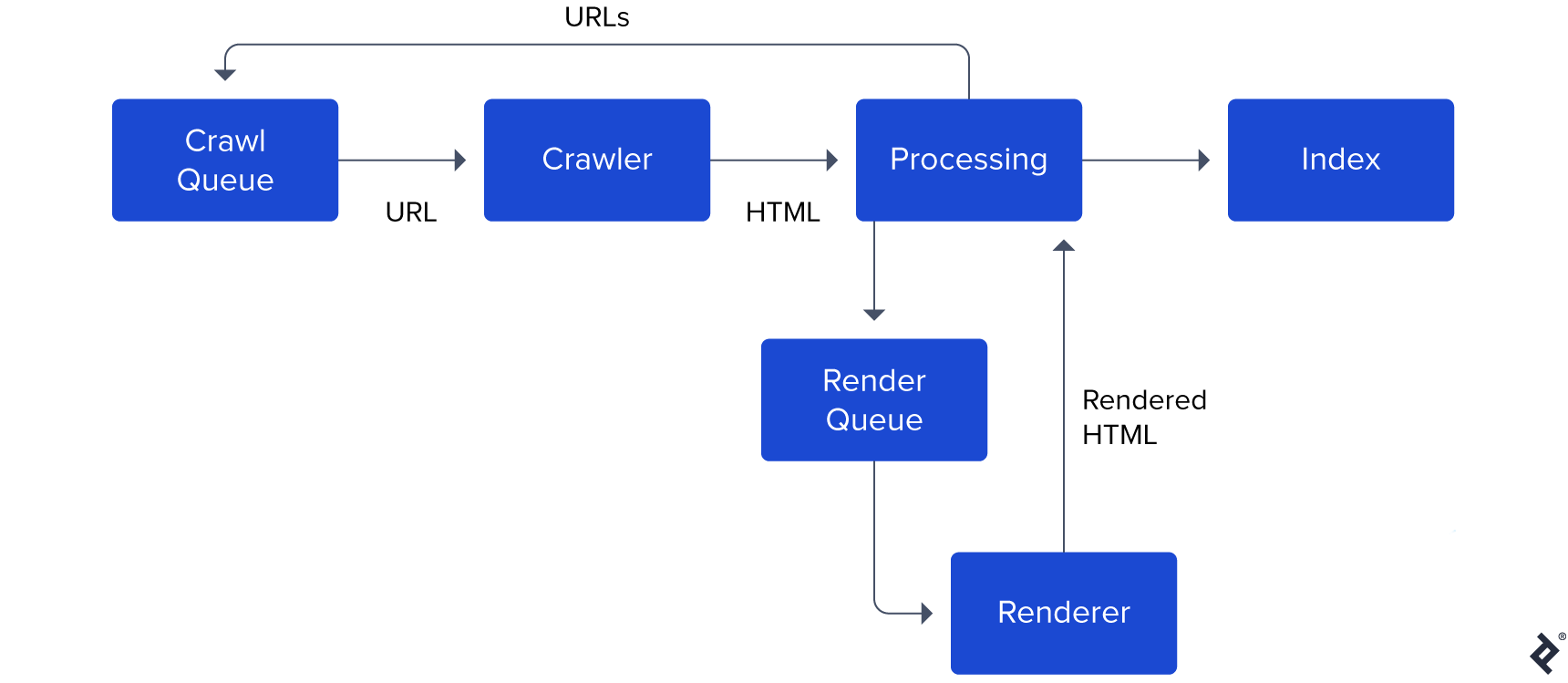

A simplified illustration from Google’s documentation provides insight: (Note: This is a simplified block diagram. The actual Googlebot is far more sophisticated.)

How Google Indexes:

- Googlebot maintains a crawl queue of URLs to crawl and index.

- When available, the crawler takes the next URL, fetches its HTML, and parses it.

- Googlebot determines if JavaScript execution is needed for content rendering. If so, the URL is added to a render queue.

- The renderer later fetches and executes the JavaScript, sending the rendered HTML back for processing.

- URLs within the webpage’s

<a> tagsare extracted and added to the crawl queue. - The content is indexed by Google.

Note the separation between Processing (HTML parsing) and Renderer (JavaScript execution) stages. This is because JavaScript execution is resource-intensive, as Googlebots handle over 130 trillion webpages. So, Googlebot prioritizes immediate HTML parsing and queues JavaScript execution. While Google states a few seconds for the render queue, it can be longer.

The concept of crawl budget is also important. Google’s crawling capacity is constrained by bandwidth, time, and available Googlebot instances, leading to resource allocation for each website’s indexing. For large, content-rich websites (e.g., e-commerce) heavily reliant on JavaScript for content rendering, Google might struggle to index everything.

Note: Google’s guidelines for managing your crawl budget can be found here.

The Challenges of React SEO

This overview of Googlebot’s process is just the beginning. Developers need to understand the obstacles search engines face when crawling and indexing React pages.

Let’s explore why React SEO can be tricky and how to address these challenges:

Empty Initial Content

React applications’ heavy reliance on JavaScript often causes issues with search engines. This is due to React’s default app shell model. The initial HTML lacks meaningful content, requiring JavaScript execution for visibility, both for users and bots.

As a result, Googlebot initially encounters a blank page, only seeing the content after rendering. This delay in content indexing can be problematic for websites with numerous pages.

Load Times and User Experience

Fetching, parsing, and executing JavaScript takes time. Additional network requests by JavaScript to retrieve content can further increase user waiting time.

Google incorporates a set of core web vitals into its ranking algorithms, emphasizing positive user experience. Prolonged loading times negatively impact this score, potentially lowering a site’s ranking.

Page Metadata

<meta> tags are essential for providing Google and social media platforms with titles, thumbnails, and descriptions. However, these platforms rely on the fetched webpage’s <head> tag, without executing JavaScript.

React renders everything, including meta tags, client-side. With a consistent app shell across the website, tailoring metadata for individual pages becomes challenging.

Sitemap Management

A sitemap provides a structured way to inform search engines about the pages, videos, and files on your site, along with their relationships. This aids search engines in crawling the site effectively.

React lacks a built-in sitemap generation mechanism. While tools exist for sitemap generation, especially with React Router for routing, they may require additional effort.

General SEO Best Practices

These points relate to broader SEO principles:

- Craft an informative URL structure to guide both users and search engines about a page’s content.

- Optimize the robots.txt file to instruct search bots on crawling your website.

- Utilize a CDN for static assets (CSS, JS, fonts) and employ responsive images to minimize load times.

Server-side rendering (SSR) and pre-rendering are viable solutions to many of these issues. We will delve into these approaches next.

The Isomorphic React Approach

The term “isomorphic” implies “similar in form.”

In the context of React, this means achieving structural similarity between the server and the client, allowing for the reuse of React components on both.

This approach allows the server to pre-render the React app, sending a complete version to users and search engines. This ensures immediate content visibility while JavaScript loads and executes in the background.

Frameworks like Next.js and Gatsby have made this approach popular. It’s important to note that isomorphic components may differ significantly from traditional React components. They might include server-side code (stripped before sending to the client) and even API keys.

While such frameworks simplify complexity, they introduce their own coding conventions. We’ll explore the performance implications later.

Before analyzing different render paths and their impact on website performance, let’s review website performance measurement.

Evaluating Website Performance

Search engines use various factors to rank websites. Beyond quick and accurate query responses, Google values websites that prioritize should have:

- Easy and fast content accessibility.

- Early interactivity for user engagement.

- Quick loading times.

- Avoidance of unnecessary data fetching or resource-intensive code to conserve user data and battery.

These factors align with the following metrics:

- Time to First Byte (TTFB): Time taken for the first bit of content to arrive after clicking a link.

- Largest Contentful Paint (LCP): Time taken for the main content of a page to become visible (ideally under 2.5 seconds).

- Time to Interactive (TTI): Time taken for a page to become interactive (scrollable, clickable, etc.).

- Bundle Size: Total size of downloaded and executed code before the page becomes fully interactive and visible.

We will revisit these metrics to understand how various rendering paths influence them.

Let’s now explore the different rendering paths available to React developers.

Understanding Render Paths

React applications can be rendered in the browser or on the server, each producing different outputs.

Two key functions, routing and code splitting, behave differently in client-side and server-side rendered apps.

Client-side Rendering (CSR)

Client-side rendering is the default for React SPAs. The server serves a shell app devoid of content. Once the browser downloads, parses, and executes the JavaScript, the HTML content is populated or rendered.

Routing is handled entirely client-side by managing browser history. This means a single HTML file serves all routes, with the client updating its view after rendering.

Code splitting is relatively simple, achievable through dynamic imports or React.lazy. This allows loading only necessary dependencies based on the route or user actions.

If content rendering requires fetching data from the server (e.g., blog post, product description), it happens after the relevant components are mounted.

Users will likely encounter a “Loading data” message or indicator during data fetching.

Client-side Rendering With Bootstrapped Data (CSRB)

Imagine the same CSR scenario, but instead of post-rendering data fetching, the server sends relevant data embedded within the served HTML.

We could have a node like this:

| |

And parse it when the component mounts:

| |

This eliminates a round trip to the server. We will analyze the trade-offs shortly.

Server-side Rendering to Static Content (SSRS)

Consider dynamically generating HTML on the fly.

For instance, an online calculator handling a query like /calculate/34+15 (ignoring URL escaping) needs to process it, calculate the result, and respond with generated HTML.

With a simple HTML structure and no need for client-side DOM manipulation, we can directly serve HTML and CSS. The renderToStaticMarkup method facilitates this.

Routing is handled entirely server-side, as each result requires recomputing HTML. CDN caching can accelerate response times. Browsers can also cache CSS for faster subsequent loads.

Server-side Rendering With Rehydration (SSRH)

Building upon the previous scenario, let’s assume we need a fully functional React application on the client.

Here, the initial render happens on the server, sending back HTML content along with JavaScript files. React then rehydrates this server-rendered markup, making the application behave like a CSR app thereafter.

React’s built-in methods enables this functionality.

The server handles the first request, while the client manages subsequent renders. Hence, such apps are known as universal React apps. Routing code might be split or duplicated between the client and server.

Code splitting becomes trickier, as ReactDOMServer lacks support for React.lazy, potentially requiring workarounds like Loadable Components.

It’s important to note that ReactDOMServer performs only a shallow render, invoking component render methods without calling lifecycle methods like componentDidMount. This necessitates refactoring to supply data to components differently.

This is where frameworks like NextJS excel. They abstract away complexities related to routing and code splitting in SSRH, providing a smoother developer experience. However, this approach may have mixed results on page performance.

Pre-rendering to Static Content (PRS)

Imagine rendering webpages before user requests, either during the build process or dynamically upon data changes.

This allows caching the generated HTML on a CDN, ensuring significantly faster delivery to users.

Pre-rendering is highly effective for blogs and e-commerce sites where content is typically not user-dependent.

Pre-rendering With Rehydration (PRH)

Similar to SSRH, we might want pre-rendered HTML to transform into a fully interactive React app on the client.

After the initial request, the application behaves like a standard React app. Routing and code-splitting functions resemble SSRH in this mode.

Render Path Performance Comparison

Let’s compare these rendering paths based on their impact on web performance metrics.

Each rendering path receives a score from 1 to 5:

1 = Unsatisfactory 2 = Poor 3 = Moderate 4 = Good 5 = Excellent

| TTFB Time to first byte | LCP Largest contentful paint | TTI Time to interactive | Bundle Size | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | 5 HTML can be cached on a CDN | 1 Multiple trips to the server to fetch HTML and data | 2 Data fetching + JS execution delays | 2 All JS dependencies need to be loaded before render | 10 |

| CSRB | 4 HTML can be cached given it does not depend on request data | 3 Data is loaded with application | 3 JS must be fetched, parsed, and executed before interactive | 2 All JS dependencies need to be loaded before render | 12 |

| SSRS | 3 HTML is generated on each request and not cached | 5 No JS payload or async operations | 5 Page is interactive immediately after first paint | 5 Contains only essential static content | 18 |

| SSRH | 3 HTML is generated on each request and not cached | 4 First render will be faster because the server rendered the first pass | 2 Slower because JS needs to hydrate DOM after first HTML parse + paint | 1 Rendered HTML + JS dependencies need to be downloaded | 10 |

| PRS | 5 HTML is cached on a CDN | 5 No JS payload or async operations | 5 Page is interactive immediately after first paint | 5 Contains only essential static content | 20 |

| PRH | 5 HTML is cached on a CDN | 4 First render will be faster because the server rendered the first pass | 2 Slower because JS needs to hydrate DOM after first HTML parse + paint | 1 Rendered HTML + JS dependencies need to be downloaded | 12 |

Conclusion

Pre-rendering to static content (PRS) delivers the best performance, while server-side rendering with hydration (SSRH) or client-side rendering (CSR) might not yield optimal results.

Hybrid approaches, combining different methods for various parts of a website, are viable. For instance, prioritizing performance metrics for public-facing pages to improve indexing, while relaxing them for private user dashboards.

Each render path has its trade-offs depending on data processing needs. The key is for engineering teams to analyze and discuss these trade-offs, choosing an architecture that maximizes user satisfaction.

Further Resources and Considerations

While I’ve covered popular techniques, this is not exhaustive. Google developers recommend exploring advanced concepts like streaming server rendering, trisomorphic rendering, and dynamic rendering (serving different content to crawlers and users) in this article.

For content-heavy websites, consider a suitable content management system (CMS) for authors, and ensure easy generation and modification of social media previews and optimize images for various screen sizes.