In this third installment of our series, we’ll finally reach the stage where our lightweight programming language can execute code. While it won’t achieve Turing-completeness or remarkable power, it will gain the capability to evaluate expressions and even interact with external functions written in C++.

My goal is to elaborate on this process as comprehensively as possible, not only because it aligns with the objective of this blog series, but also for my personal documentation. This aspect became particularly crucial in this part, as the complexity increased.

While I began coding for this part before publishing the second article, it became evident that the expression parser warranted a dedicated blog post due to its standalone nature.

This separation, along with the utilization of certain programming techniques that some might consider unconventional, helped prevent this part from becoming excessively lengthy. Nevertheless, it’s likely that some readers will question the rationale behind employing these techniques.

Why Employ Macros?

Throughout my programming journey, working on diverse projects and collaborating with various individuals, I’ve observed a tendency among developers to gravitate towards dogmatism—perhaps because it simplifies matters.

The first programming dogma dictates that the goto statement is inherently flawed, detrimental, and should be avoided at all costs. While I comprehend the sentiment behind this belief and concur with it in the majority of instances where goto is employed, it’s important to acknowledge that breaking out of nested loops in C++ can be effortlessly achieved using goto. The alternative, often involving a bool variable or a dedicated function, can potentially hinder readability compared to code that adheres to this dogmatic restriction.

The second dogma, particularly relevant to C and C++ developers, asserts that macros are inherently problematic, hazardous, and essentially disasters waiting to happen. This stance is often accompanied by the following illustrative example:

| |

Subsequently, the question arises: What is the value of x after executing this code snippet? The answer is 5 because x is incremented twice, once on each side of the ? operator.

The crux of the matter is that this scenario doesn’t represent a typical use case for macros. Macros become problematic when employed in situations where ordinary functions would suffice, especially if they masquerade as functions, thereby obscuring their side effects from the user. However, our utilization of macros will not mimic functions, and we will employ block letters for their names to clearly distinguish them as non-functions. While we acknowledge the drawback of limited debugging capabilities, we accept this trade-off as the alternative—copy-pasting identical code multiple times—poses a significantly higher risk of errors compared to employing macros. One potential solution would be to develop a code generator, but why reinvent the wheel when C++ already provides one?

Programming dogmas, in most cases, are counterproductive. The use of “almost” here is deliberate to avoid falling into the same dogmatic trap I’ve just highlighted.

The code and all macros for this part are accessible here.

Variables

In the previous part, I mentioned that Stork wouldn’t be compiled into traditional binary code or assembly language. However, I also stated that it would maintain static typing. Consequently, while compilation will occur, the output will be a C++ object capable of execution. This will become clearer later. For now, it’s sufficient to understand that all variables will be represented as individual objects.

To manage these objects within a global variable container or on the stack, a convenient approach is to define a base class and derive from it.

| |

As evident, this base class is straightforward. The clone function, responsible for deep copying, represents its sole virtual member function apart from the destructor.

Since we’ll consistently interact with objects of this class through shared_ptr, inheriting from std::enable_shared_from_this makes sense, simplifying the retrieval of shared pointers. The function static_pointer_downcast is provided for convenience, as we’ll frequently need to downcast from this class to its concrete implementations.

The actual implementation of this class is variable_impl, parameterized by the type it encapsulates. We’ll instantiate it for the four types we’ll utilize:

| |

We’ll employ double for numeric values. Strings, being immutable, will be reference-counted to enable optimizations when passed by value. Arrays will be represented using std::deque due to its stability. It’s worth noting that runtime_context will encapsulate all pertinent information about program memory during runtime, a topic we’ll revisit later.

The following definitions will also be frequently used:

| |

The “l” here serves as an abbreviation for “lvalue.” Whenever we deal with an lvalue of a specific type, we’ll utilize a shared pointer to variable_impl.

Runtime Context

During program execution, the runtime_context class will maintain the memory state.

| |

Initialization occurs with the count of global variables.

_globalsstores all global variables, accessible via theglobalmember function using absolute indices._stackhouses local variables and function arguments, while the integer at the top of_retval_idxtracks the absolute index within_stackof the current return value.- The return value is accessed through the

retvalfunction, whereas local variables and function arguments are accessed using thelocalfunction by providing indices relative to the current return value. Function arguments, in this case, have negative indices. - The

pushfunction adds variables to the stack, whileend_scoperemoves a specified number of variables from the stack. - The

callfunction expands the stack by one element and pushes the index of the last element in_stackonto_retval_idx. end_functionremoves the return value and a specified number of arguments from the stack, returning the removed return value.

We won’t implement any low-level memory management, relying instead on C++’s native memory management. Similarly, we won’t delve into heap allocations, at least not for now.

With runtime_context in place, we possess all the fundamental components required for the core and most intricate aspect of this part.

Expressions

To elucidate the intricate solution presented here, I’ll briefly touch upon a couple of unsuccessful attempts that paved the way for this approach.

The most straightforward approach involved evaluating every expression as a variable_ptr and defining the following virtual base class:

| |

Subsequently, we would derive from this class for each operation, such as addition, concatenation, function calls, and so on. For instance, the implementation of an addition expression might resemble this:

| |

This approach entails evaluating both sides (_expr1 and _expr2), adding them, and then constructing a variable_impl<number>.

Downcasting variables wouldn’t pose an issue since their types are verified during compile time. However, the primary concern lies in the performance overhead introduced by the heap allocation of the returned object, which, in theory, is unnecessary. This allocation stems from the need to satisfy the virtual function declaration. While the first version of Stork will tolerate this penalty when returning numbers from functions, it’s unacceptable for simple pre-increment expressions to incur such an overhead.

As an alternative, I explored type-specific expressions inheriting from a common base:

| |

This represents merely a fragment of the hierarchy (specifically for numbers), and already, we encounter the diamond problem (a class inheriting from two classes sharing a common base class).

Fortunately, C++ offers virtual inheritance, allowing inheritance from a base class while maintaining a pointer to it within the derived class. Consequently, if classes B and C virtually inherit from A, and class D inherits from both B and C, there will be only one instance of A within D.

However, this approach comes with certain trade-offs, including performance implications and the inability to downcast from A. Nonetheless, it seemed like a viable opportunity to leverage virtual inheritance.

With this approach, the implementation of the addition expression becomes more intuitive:

| |

Syntactically, it’s quite satisfactory. However, if any inner expression represents an lvalue number expression, it would necessitate two virtual function calls for evaluation—not ideal, but not entirely disastrous either.

Let’s introduce strings into the mix and observe the consequences:

| |

To enable the conversion of numbers to strings, we need to inherit number_expression from string_expression.

| |

While we’ve managed to overcome this hurdle, we’re forced to override the evaluate virtual method once more. Otherwise, we’ll encounter significant performance degradation due to unnecessary conversions from numbers to strings.

As evident, the design is becoming increasingly convoluted. It barely survives because we lack bidirectional type conversions between expressions. If such a scenario arose, or if we attempted any form of circular conversion, our hierarchy would crumble. After all, hierarchies should reflect “is-a” relationships, not the weaker “is-convertible-to” relationship.

These unsuccessful attempts led me to a more intricate yet, in my view, more appropriate design. Firstly, having a single base class isn’t strictly necessary. While we need an expression class that can evaluate to void, if we can differentiate between void expressions and others during compile time, runtime conversions become unnecessary. Consequently, we’ll parameterize the base class with the expression’s return type.

Here’s the complete implementation of this class:

| |

This ensures only one virtual function call per expression evaluation (recursive calls aside). Given that we’re not compiling to binary code, this is a favorable outcome. The only remaining task is handling type conversions where permitted.

To achieve this, we’ll parameterize each expression with its return type and inherit from the corresponding base class. Within the evaluate function, we’ll convert the evaluation result to the function’s return type.

For instance, consider our addition expression:

| |

To implement the convert function, we require some infrastructure:

| |

The is_boxed structure is a type trait containing an inner constant, value, evaluating to true if and only if the first parameter is a shared pointer to variable_impl parameterized with the second type.

Implementing the convert function would be feasible even in earlier C++ versions. However, C++17 introduced a valuable statement called if constexpr, which evaluates conditions at compile time. If the condition is false, the corresponding block is entirely discarded, even if it would lead to a compile-time error. Otherwise, the else block is discarded.

| |

Let’s analyze this function:

- Conversion occurs if permissible in C++ (for

variable_implpointer upcasting). - Unboxing takes place if the value is boxed.

- Conversion to a string happens if the target type is a string.

- No action is taken if the target type is void.

In my opinion, this is significantly more readable than the older SFINAE-based syntax.

I’ll provide a concise overview of expression types, omitting some technical nuances for brevity.

We have three primary types of leaf expressions in an expression tree:

- Global variable expressions

- Local variable expressions

- Constant expressions

| |

Apart from the return type, it’s also parameterized by the variable type. Local variables are handled similarly. For constants, we have:

| |

Here, we immediately convert the constant within the constructor.

This serves as the base class for most of our expressions:

| |

The first argument represents the functor type, instantiated and called during evaluation. The remaining types correspond to the return types of child expressions.

To minimize boilerplate code, we define three macros:

| |

Note that operator() is defined as a template, although it’s not always strictly necessary. This consistent approach simplifies expression definitions compared to specifying argument types as macro arguments.

Now, we can define most expressions. For instance, here’s the definition for /=:

| |

We can define almost all expressions using these macros. Exceptions include operators with defined argument evaluation orders (logical && and ||, ternary (?), and comma (,) operators), array indexing, function calls, and param_expression, which clones parameters for pass-by-value function arguments.

Implementing these exceptions is relatively straightforward. Function call implementations are the most complex, so let’s examine one:

| |

This code prepares the runtime_context by pushing all evaluated arguments onto its stack and invoking the call function. It then calls the evaluated first argument (representing the function itself) and returns the result of the end_function method. We can observe the use of if constexpr here as well, allowing us to avoid writing specializations for the entire class to handle functions returning void.

With this, we have all the runtime expression-related components. The final piece involves converting the parsed expression tree (described in the previous blog post) into a tree of expressions.

Expression Builder

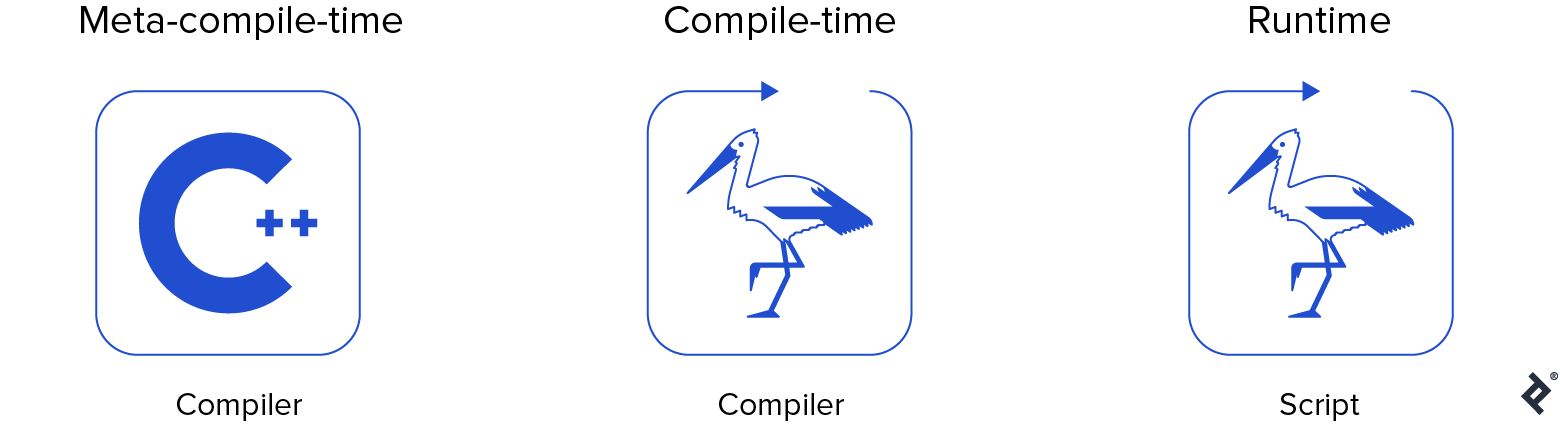

To avoid confusion, let’s define the distinct phases of our language development cycle:

- Meta-compile time: When the C++ compiler executes.

- Compile time: When the Stork compiler executes.

- Runtime: When the Stork script executes.

Here’s the pseudo-code for the expression builder:

| |

While handling all operations is necessary, the algorithm itself appears straightforward.

Unfortunately, this approach is flawed. Firstly, we need to specify the function’s return type, which isn’t fixed in this case. The return type depends on the type of node being visited. While node types are known at compile time, return types should be determined at meta-compile time.

In the previous post, I expressed skepticism about the advantages of dynamically typed languages. In such languages, implementing the pseudo-code shown above would be almost literal. Now, I’m quite aware of their merits—instant karma at its finest.

Fortunately, we know the type of the top-level expression. While it depends on the compilation context, we can determine it without parsing the entire expression tree. For instance, consider the following for loop:

| |

The first and third expressions have a void return type because their evaluation results are unused. However, the second expression has a number type because it’s compared to zero to determine whether to terminate the loop.

Knowing the type of the expression associated with a node operation often reveals the types of its child expressions.

For example, if the expression (expression1) += (expression2) has the type lnumber, it implies that expression1 also has the type lnumber, while expression2 has the type number.

However, the expression (expression1) < (expression2) always results in a number, even though its child expressions can be either number or string. In this case, we check if both nodes represent numbers. If so, we build expression1 and expression2 as expression<number>. Otherwise, they become expression<string>.

Another challenge we must address involves handling incompatible types during expression building.

Imagine needing to build an expression of type number. We cannot return anything meaningful if we encounter a concatenation operator. While we know this shouldn’t happen due to type checking during expression tree construction (in the previous part), it prevents us from writing a template function parameterized by the return type. Such a function would have invalid branches depending on the return type.

One approach could involve splitting the function based on the return type using if constexpr. However, this is inefficient, as repeating code for the same operation across multiple branches becomes necessary. Writing separate functions in such cases might be preferable.

The implemented solution splits the function based on the node type. Within each branch, we check if that branch’s type is convertible to the function’s return type. If not, a compiler error is thrown. While this should never occur ideally, the code’s complexity makes such a strong claim risky—I might have made a mistake.

We use the following self-explanatory type trait structure to check for convertibility:

| |

After this split, the code becomes relatively straightforward. We can semantically cast from the original expression type to the desired one without encountering meta-compile-time errors.

However, this approach introduces a significant amount of boilerplate code, prompting heavy reliance on macros for reduction.

| |

The build_expression function represents the sole public function here. It invokes std::visit on the node type, applying the provided functor to the variant and decoupling it in the process. You can find more information about this and the overloaded functor here.

The RETURN_EXPRESSION_OF_TYPE macro calls private functions for expression building and throws an exception if conversion is impossible:

| |

We must return a null pointer in the else branch because the compiler cannot determine the function’s return type if conversion is impossible. Otherwise, std::visit requires all overloaded functions to have identical return types.

For example, here’s the function for building expressions with string as the return type:

| |

It first checks if the node contains a string constant and builds a constant_expression accordingly.

Next, it checks if the node holds an identifier and returns a global or local variable expression of type lstring. This scenario can occur if we implement constant variables. Otherwise, it assumes the node contains a node operation and attempts all operations that can yield a string.

Here are the implementations of the CHECK_IDENTIFIER and CHECK_BINARY_OPERATION macros:

| |

| |

The CHECK_IDENTIFIER macro needs to consult the compiler_context to construct a global or local variable expression with the correct index. This is the only instance where compiler_context is used within this structure.

As you can see, CHECK_BINARY_OPERATION recursively calls build_expression for its child nodes.

Wrapping Up

You can access the complete source code my GitHub page, compile it, input expressions, and observe the evaluated variable results.

I believe that in all creative endeavors, there comes a moment when the creator realizes their creation has, in a sense, come alive. For programming language construction, it’s the moment when you witness the language “breathing.”

In the next and final installment of this series, we’ll implement the remaining features of our minimal language and see it in action.