This installment of our series delves into a challenging aspect of scripting language development: creating an expression parser, a fundamental component of any programming language.

One might wonder: Why not leverage existing tools or libraries?

Why not employ Lex, YACC, Bison, Boost Spirit, or even regular expressions?

My wife has observed a peculiar habit of mine: I tend to enumerate reasons when confronted with tough questions, perhaps hoping quantity will compensate for any lack of quality in my response.

Let’s apply this approach now.

- I aim to utilize standard C++, specifically C++17. The language itself is quite comprehensive, and I’m resisting the temptation to incorporate anything beyond the standard library.

- During the development of my first scripting language, time constraints and a lack of familiarity with tools like Lex or YACC led me to implement everything manually.

- Subsequently, I stumbled upon a blog post by a seasoned programming language developer who cautioned against relying on such tools. He argued that these tools address the simpler aspects of language development, ultimately leaving you to grapple with the more intricate challenges. Regrettably, I cannot locate that particular blog post now—it was a time when both the internet and I were in our youth.

- Back then, a prevalent meme stated: “You have a problem, and you decide to solve it with regular expressions. Now you have two problems.”

- While I am acquainted with Boost Spirit and acknowledge its utility as a library, I still prefer to maintain finer control over the parser.

- I derive satisfaction from manually implementing these components. Honestly, I could simply offer this explanation and dispense with the list entirely.

The complete source code is available at my GitHub page.

Token Iterator

This section outlines some modifications made to the code from Part 1.

These changes primarily consist of minor adjustments and fixes. However, a notable enhancement to the existing parsing code is the introduction of the token_iterator class. This class enables us to examine the current token without extracting it from the stream, which proves to be quite convenient.

| |

Initialization occurs with push_back_stream, and subsequent dereferencing and incrementation become possible. An explicit boolean cast allows for checking, evaluating to false when the current token corresponds to the end-of-file (eof).

Statically or Dynamically Typed?

This part necessitates a crucial decision: Will the language be statically or dynamically typed?

Statically typed languages enforce type checking during compilation, whereas dynamically typed languages defer this process to runtime. Consequently, potential errors in dynamically typed languages may lurk undetected until execution.

Statically typed languages clearly hold an advantage in this regard, as early error detection is always desirable. The primary advantage of dynamically typed languages, in my view, lies in the ease of development.

My previous scripting language employed dynamic typing and proved relatively straightforward to implement, including the expression parser. The absence of explicit type checking simplifies the process, relying instead on runtime errors that are relatively easy to handle.

For instance, implementing the binary + operator for numerical addition only requires evaluating both operands as numbers at runtime. If either operand fails this evaluation, an exception is thrown. In my previous implementation, I even incorporated operator overloading by inspecting the runtime type information of variables and operators within expressions.

My initial foray into language development (this being my third attempt) involved type checking during compilation, but it didn’t fully exploit the benefits. Expression evaluation still relied on runtime type information.

For this iteration, I’ve opted for static typing, which has proven to be more challenging than anticipated. However, since I’m not aiming for binary compilation or any form of emulated assembly code, some type information will inherently persist in the compiled output.

Types

Our basic type system will encompass the following:

- Numbers

- Strings

- Functions

- Arrays

While we may expand this set later, structures (or classes, records, tuples, etc.) will be omitted initially. However, our design will accommodate future extensions, avoiding choices that would make such additions difficult.

Representing types as strings with parsing conventions seemed cumbersome. Implementing them as classes with shared pointers felt excessive.

Ultimately, I settled on a type registry:

| |

Basic types are defined within an enum:

| |

The nothing enum member serves as a stand-in for void, which is a reserved keyword in C++.

Array types are represented by a structure containing a type_handle member:

| |

Note that array lengths are not included in array_type, implying dynamic resizing. We’ll address this using std::deque or a similar mechanism later.

Function types consist of the return type, parameter types, and whether parameters are passed by value or reference:

| |

Now, let’s define the class responsible for managing these types:

| |

Types are stored in a std::set to ensure pointer stability even when new types are inserted. The get_handle function registers a given type and returns a pointer to it. If the type is already present, it returns a pointer to the existing entry. Convenience functions are provided for retrieving primitive types.

Regarding implicit conversions, numbers will be convertible to strings. This should be safe, as the reverse conversion is not permitted, and the string concatenation operator (..) is distinct from the numerical addition operator. Even if this conversion is later removed, it serves as a valuable exercise. This required modifying the number parser to handle . as a potential concatenation operator instead of solely a decimal point.

Compiler Context

During compilation, various functions require access to information about the code being processed. We’ll store this information in a compiler_context class. For expression parsing, we’ll need to retrieve details about encountered identifiers.

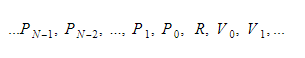

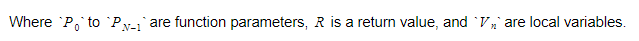

Runtime variables will reside in two containers: a global variable container and a stack. The stack expands upon function calls and scope entry, and it contracts upon function returns and scope exit. Function parameters are pushed onto the stack during calls, and the return value is pushed upon function completion. Therefore, for each function, the stack structure will resemble this:

Functions will track the absolute index of their return variable, and variables or parameters will be accessed relative to this index.

Currently, functions are treated as constant global identifiers.

Here’s the class definition for identifier information:

| |

For local variables and function parameters, index returns the index relative to the return value. For global identifiers, it returns the absolute global index.

Three distinct identifier lookup mechanisms will be available in compile_context:

- Global identifier lookup, stored by value within

compile_contextas it remains constant throughout compilation. - Local identifier lookup, represented by a

unique_ptr, which is initialized tonullptrin the global scope and within functions. Upon entering a scope, a new local context is created with the previous context as its parent. When exiting a scope, the current context is replaced by its parent. - Function identifier lookup, using a raw pointer. This pointer is

nullptrin the global scope and points to the outermost local scope within a function.

| |

Expression Tree

Parsed expression tokens are transformed into an expression tree, which, like any tree, comprises nodes.

Two types of nodes exist:

- Leaf nodes, representing: a) Identifiers b) Numbers c) Strings

- Inner nodes, representing operations on child nodes, storing children as

unique_ptr.

Each node carries information about its type and whether it yields an lvalue (a value that can appear on the left side of the = operator).

Inner node creation involves attempting to convert the return types of child nodes to the expected types. Permitted implicit conversions include:

- lvalue to non-lvalue

- Any type to

void numbertostring

If a conversion is disallowed, a semantic error is thrown.

Here’s the class definition, omitting some helper functions and implementation details:

| |

Most method functionalities are self-explanatory. The check_conversion function verifies if a type can be converted to the provided type_id and lvalue flag according to the conversion rules, throwing an exception if the conversion is not permitted.

Nodes initialized with std::string or double are assigned types string or number respectively and are not considered lvalues. Nodes initialized with identifiers inherit the identifier’s type and are considered lvalues unless the identifier is constant.

Nodes initialized with node operations have their types determined by the operation and, in some cases, the types of their children. Let’s summarize expression types in a table. An & suffix denotes an lvalue. Parentheses group expressions treated identically.

Unary Operations

| Operation | Operation type | x type |

| ++x (--x) | number& | number& |

| x++ (x--) | number | number& |

| +x (-x ~x !x) | number | number |

Binary Operations

| Operation | Operation type | x type | y type |

| x+y (x-y x*y x/y x\y x%y x&y x|y x^y x<<y x>>y x&&y x||y) | number | number | number |

| x==y (x!=y x<y x>y x<=y x>=y) | number | number or string | same as x |

| x..y | string | string | string |

| x=y | same as x | lvalue of anything | same as x, without lvalue |

| x+=y (x-=y x*=y x/=y x\=y x%=y x&=y x|=y x^=y x<<=y x>>=y) | number& | number& | number |

| x..=y | string& | string& | string |

| x,y | same as y | void | anything |

| x[y] | element type of x | array type | number |

Ternary Operations

| Operation | Operation type | x type | y type | z type |

| x?y:z | same as y | number | anything | same as y |

Function Call

Function calls introduce additional complexity. For a function with N arguments, the function call operation has N+1 children. The first child represents the function itself, and the remaining children correspond to the arguments.

Implicit passing of arguments by reference is disallowed. Callers must explicitly use the & prefix. Currently, this is not treated as a separate operator but rather as part of the function call parsing logic. If an ampersand is expected but not parsed, the lvalue-ness of the argument is removed by introducing a dummy unary operation called node_operation::param. This operation preserves the child’s type but removes its lvalue property.

During node construction for a function call, an error is generated if an lvalue argument is encountered when the function doesn’t expect one, indicating an accidental ampersand. Interestingly, if treated as an operator, & would have the lowest precedence, as it lacks semantic meaning when parsed within an expression. This might change later.

Expression Parser

Edsger Dijkstra, a prominent figure in computer science, once remarked:

“It is practically impossible to teach good programming to students that have had a prior exposure to BASIC. As potential programmers, they are mentally mutilated beyond hope of regeneration.”

Those fortunate enough to have evaded BASIC’s influence should consider themselves fortunate, having escaped “mental mutilation.”

For the rest of us, the “mutilated” programmers, let’s reminisce about our BASIC coding days. BASIC had the \ operator for integer division, which was quite useful in a language lacking separate integer and floating-point types. I’ve incorporated this operator into Stork, along with \=, which performs integer division followed by assignment.

I suspect JavaScript programmers, for instance, would appreciate such operators. One can only speculate what Dijkstra would say about them if he had witnessed the rise of JavaScript.

Speaking of JavaScript, one of my biggest gripes is the inconsistency in these expressions:

"1" - "1"evaluates to0"1" * "1"evaluates to1"1" / "1"evaluates to1"1" + "1"evaluates to"11"

The Croatian hip-hop group “Tram 11,” named after a tram route in Zagreb, had a song with lyrics roughly translating to: “One and one are not two, but 11.” This song predates JavaScript but aptly illustrates the discrepancy.

To circumvent such issues, I’ve prohibited implicit conversions from strings to numbers and introduced the .. operator for concatenation (and ..= for concatenation with assignment). The origin of this operator eludes me—it’s not from BASIC or PHP. I’d rather not Google “Python concatenation,” as Python-related searches tend to give me the creeps. My phobia of snakes combined with “concatenation” is not a pleasant thought. Perhaps I’ll explore this further later using an archaic text-based browser devoid of ASCII art.

Returning to the main topic, our expression parser will be an adaptation of the “Shunting-yard Algorithm.”

This algorithm is relatively straightforward and likely comes to mind for most programmers after some consideration. It can evaluate infix expressions or convert them to reverse Polish notation notation, which is not our goal here.

The algorithm reads operands and operators sequentially from left to right. Operands are pushed onto an operand stack. Operators, however, cannot be evaluated immediately due to precedence rules. They are pushed onto an operator stack.

Before pushing an operator, the algorithm checks if the operator at the top of the stack has higher precedence than the newly read operator. If so, the top operator is evaluated using operands from the operand stack, and the result is pushed back onto the operand stack. This process continues until the entire expression is read. Then, all remaining operators on the operator stack are evaluated with operands from the operand stack, pushing results back onto the operand stack. Ultimately, a single operand remains on the stack, representing the final result.

For operators with equal precedence, left-associative operators are evaluated first; otherwise, right-associative operators take precedence. Operators with the same precedence cannot have different associativity.

While the original algorithm handles parentheses, our implementation will address them recursively for code clarity.

Edsger Dijkstra coined the term “Shunting-yard” due to the algorithm’s resemblance to the operations of a railroad shunting yard.

However, the original algorithm lacks robust error checking, potentially parsing invalid expressions as valid ones. To address this, I’ve introduced a boolean variable to track whether an operator or operand is expected. When expecting operands, unary prefix operators can also be parsed. This ensures comprehensive expression syntax checking, preventing invalid expressions from slipping through.

In Conclusion

Initially, I intended to cover both expression parsing and expression building in this part. However, the complexity exceeded the scope of a single post. This part focused on expression parsing, and I’ll elaborate on building expression objects in the next installment.

If memory serves, it took me a single weekend to create the first version of my first language some 15 years ago. This makes me wonder where things went astray this time.

Rather than acknowledging my advancing age and diminishing wit, I’ll attribute the delay to my demanding two-year-old son, who consumes much of my free time.

As in Part 1, feel free to examine, download, or even compile the code from my GitHub page.