If you’re a fan of whales or simply interested in streamlining your software delivery process, this Docker tutorial is for you. Software containers are rapidly shaping the future of IT, so let’s dive in with industry giants like Moby Dock and Molly.

Docker, symbolized by a whale logo, is an open-source project that simplifies application deployment within software containers. Its core functionality leverages resource isolation features of the Linux kernel while providing a user-friendly API. Since its debut in 2013, Docker’s popularity has skyrocketed, with major companies like eBay, Spotify, and Baidu embracing it](https://www.docker.com/customers). With recent funding reaching Docker has landed a huge $95 million, it’s poised to become a cornerstone of [DevOps practices.

The Shipping Container Analogy

Docker’s core concept can be illustrated with an analogy from the shipping industry. Goods transport involves various equipment like forklifts, trucks, trains, cranes, and ships. These goods come in diverse shapes, sizes, and with different handling requirements. Traditionally, this process was labor-intensive, requiring manual intervention at each stage.

The advent of standardized shipping containers revolutionized this process. With uniform sizes and transport-focused design, these containers facilitated automation, minimizing manual handling. The sealed containers also provided controlled environments, preserving the integrity of sensitive goods. Consequently, the industry could prioritize efficient A-to-B transport over individual cargo concerns.

Docker brings these same advantages to the software world.

Docker vs. Virtual Machines

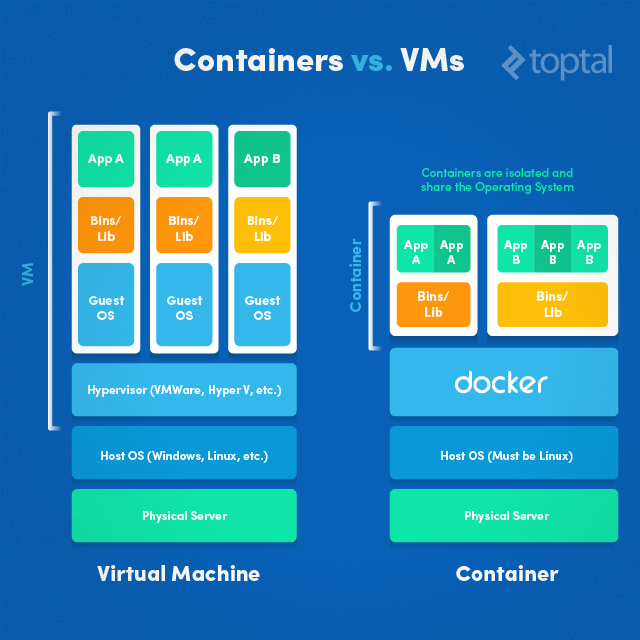

While seemingly similar, virtual machines and Docker containers have key differences, as highlighted in this diagram:

Applications within virtual machines require a full operating system instance and libraries, in addition to the hypervisor. Containers, however, share the host’s operating system. The container engine (Docker in the image) functions similarly to a hypervisor, managing container lifecycles. However, processes inside containers run like native host processes, without the overhead of hypervisor execution. This allows applications to share libraries and data between containers.

Both technologies have their strengths, making hybrid systems combining virtual machines and containers increasingly common. A prime example is Boot2Docker, covered in the Docker installation section.

Docker Architecture

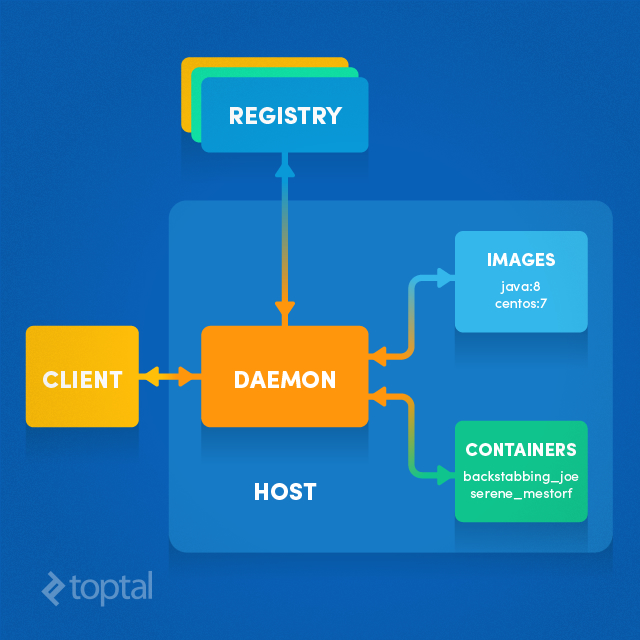

At the top of the architecture are registries. The default, Docker Hub, hosts public and official images. Organizations can also establish private registries.

Images and containers reside on the right side. Images are downloaded from registries, either explicitly (docker pull imageName) or automatically when starting a container, and are locally cached.

Containers are active instances of images. Multiple containers can originate from a single image.

The Docker daemon, at the center, oversees container creation, execution, and monitoring. It also handles image building and storage.

On the left is the Docker client, communicating with the daemon via HTTP. Unix sockets are used locally, but remote management is possible through the HTTP-based API.

Installing Docker

For the most up-to-date instructions, refer to the official documentation.

Docker is native to Linux, making installation as simple as sudo apt-get install docker.io on some distributions. Refer to the documentation for specifics. While Docker commands in Linux typically require sudo, it will be omitted in this article for readability.

Docker’s reliance on Linux kernel features makes native execution on Mac OS or Windows impossible. Instead, Boot2Docker, an application bundling a VirtualBox Virtual Machine, Docker, and management utilities, is used. Follow the official instructions for MacOS and Windows to install Docker on these platforms.

Using Docker

Let’s start with a basic example:

| |

Expected output:

| |

Behind the scenes, several actions transpired:

- The ‘phusion/baseimage’ image was fetched from Docker Hub (unless locally cached).

- A container was initiated from this image.

- The echo command ran within the container.

- The container stopped upon command completion.

Initial runs might experience a slight delay. A cached image would result in near-instantaneous execution. Details of the last container are shown using docker ps -l:

| |

Diving Deeper

Running a basic command in Docker is similar to a standard terminal. To demonstrate a more practical scenario, we’ll deploy a simple web server application using Docker. This Java program will respond to HTTP GET requests to ‘/ping’ with “pong\n”.

| |

Dockerfile

Before creating a Docker image, explore existing options on Docker Hub or private registries. For instance, we’ll utilize the official java:8 image instead of installing Java.

Choosing a base image is the first step, indicated by the FROM instruction. We’ll use the official Java 8 image. The COPY instruction copies our Java file into the image. RUN compiles the code, while EXPOSE signifies the port for service exposure. ENTRYPOINT defines the execution command upon container startup, and CMD specifies default parameters for this command.

| |

Save these instructions in a “Dockerfile”, then build the Docker image:

| |

Docker’s official documentation provides a comprehensive section dedicated to best practices for creating Dockerfiles.

Running Containers

Once the image is built, we can create a running instance, a container. There are multiple ways to achieve this, but let’s start with a straightforward approach:

| |

Here, -p [port-on-the-host]:[port-in-the-container] maps ports between the host and container. The -d flag runs the container as a background daemon process. Test the web server by accessing ‘http://localhost:8080/ping’. On platforms using Boot2docker, replace ’localhost’ with the virtual machine’s IP address where Docker runs.

On Linux:

| |

On platforms using Boot2Docker:

| |

A successful response should be:

| |

Congratulations, our custom Docker container is up and running! Starting the container in interactive mode -i -t, overriding the entrypoint to access a bash terminal, is also possible. We are then free to run commands, but exiting the container will terminate it:

| |

Container startup involves numerous options. For instance, the -v flag shares the host filesystem with the container, allowing data persistence outside the container. By default, access is read-write, modifiable to read-only using :ro appended to the container’s volume path. Volumes are crucial for handling sensitive data like credentials, preventing storage within the image. They also prevent data duplication, such as mapping your local Maven repository to avoid redundant downloads.

Docker also enables container linking. Linked containers communicate directly, even without exposed ports. This is achieved with –link other-container-name. Here’s an example combining these parameters:

| |

Container and Image Operations

Numerous operations can be performed on containers and images. Here are a few:

- stop: Halts a running container.

- start: Resumes a stopped container.

- commit: Generates a new image from a container’s changes.

- rm: Deletes one or more containers.

- rmi: Deletes one or more images.

- ps: Lists containers.

- images: Lists images.

- exec: Executes a command within a running container.

The last command is particularly helpful for debugging, as it provides terminal access to a running container:

| |

Docker Compose: Orchestrating Microservices

For managing multiple interconnected containers, tools like docker-compose are invaluable. A configuration file defines container startup and linking procedures. Regardless of the number of containers and their dependencies, a single command docker-compose up brings them all online.

Docker in Action

Let’s examine how Docker benefits different project stages.

Development

Docker streamlines local development environments. Instead of juggling multiple versions of services like Java, Kafka, Spark, or Cassandra, start and stop required containers as needed. This enables running multiple software stacks simultaneously without dependency conflicts.

Docker saves time, effort, and resources. For complex project setups, “dockerize” them. Invest the initial effort in creating a Docker image, and everyone benefits from instant container startup.

Establish a local (or CI-based) “integration environment” where stubs are replaced by real services running in Docker containers.

Testing / Continuous Integration

Dockerfiles facilitate reproducible builds. Configure Jenkins or other CI solutions to generate Docker images for each build. Store these images in a private Docker registry for future use.

Docker ensures that testing focuses on the application, not the environment. Executing tests within a running container enhances predictability.

Leverage containerization to create slave machines with identical development setups effortlessly. This is particularly useful for load testing clustered deployments.

Production

Docker bridges the gap between developers and operations, minimizing friction. It promotes consistent image/binary usage throughout the pipeline. Deploying fully tested containers without environmental discrepancies minimizes errors during deployment.

Seamlessly migrate applications into production. What was once complex and error-prone becomes as simple as:

| |

Rollback or switch to a different container instantly if issues arise during deployment:

| |

… all without leaving inconsistencies or residue.

Summary

Docker’s motto encapsulates its essence: Build, Ship, Run.

- Build: Compose applications from microservices, ensuring consistency between development and production without platform or language lock-in.

- Ship: Design, test, and distribute applications with a unified workflow and consistent user interface.

- Run: Deploy scalable services securely and reliably across diverse platforms.

Enjoy your journey into the world of Docker!

This article draws inspiration from Adrian Mouat’s insightful book Using Docker.