Could you please take a look at our system? Our previous software developer is no longer available, and we’ve encountered several issues. We need someone to review and refine it for us.

Anyone with experience in software engineering understands that this seemingly straightforward request often marks the start of a project “destined for disaster.” Taking over someone else’s code can be a nightmare, particularly when it’s poorly structured and lacks documentation.

So, when a customer recently asked me to examine and enhance his existing socket.io chat server application (built with [Node.js), I was understandably cautious. However, before dismissing the request entirely, I decided to at least review the codebase.

Unfortunately, my concerns were only amplified upon examining the code. The chat server was implemented as a single, massive JavaScript file. Transforming this monolithic file into a well-architected, maintainable piece of software would be a considerable challenge. Nevertheless, I thrive on challenges, so I agreed to proceed.

Initial Assessment - Gearing Up for Reengineering

The existing software consisted of a single file containing 1,200 lines of undocumented code. A daunting prospect, to say the least. Adding to the challenge, the code was known to have bugs and performance issues.

Examining the log files (always a prudent starting point when inheriting code) revealed potential memory leaks. The process was reportedly consuming over 1GB of RAM at times.

These issues made it immediately clear that code reorganization and modularization were necessary before even attempting to debug or enhance the business logic. Some initial areas needing attention included:

- Code Structure. The code lacked a coherent structure, blurring the lines between configuration, infrastructure, and business logic. There was essentially no modularization or separation of concerns.

- Code Duplication. Certain code segments, like error handling for event handlers and web request code, were duplicated throughout the codebase. Code repetition is detrimental, making maintenance harder and increasing the likelihood of errors when changes are made in one location but not others.

- Hardcoded Values. The code relied on numerous hardcoded values, a practice generally best avoided. Allowing modification of these values through configuration parameters instead of requiring code changes would enhance flexibility and aid testing and debugging.

- Logging. The logging system was rudimentary, generating a single, massive log file that was cumbersome to analyze and parse.

Core Architectural Goals

While restructuring the code, I wanted to address not only the specific issues identified but also some key architectural objectives that should guide the design of any software system. These included:

- Maintainability. Code should never be written with the assumption that only the original author will maintain it. Clarity, understandability, and ease of modification and debugging for others are crucial.

- Extensibility. Assuming current functionality will suffice in the future is a recipe for trouble. Software architecture should prioritize ease of extension.

- Modularity. Functionality should be segregated into logical, distinct modules, each with a clear purpose and function.

- Scalability. Modern users demand near-instantaneous response times. Poor performance and high latency can doom even the most useful application. Scalability addresses how software performs as concurrent users and bandwidth demands increase. Techniques like parallelization, database optimization, and asynchronous processing help maintain system responsiveness under load.

Restructuring the Codebase

The goal was to transform the monolithic source code file into a set of modular, well-architected components. This would yield code that was significantly easier to maintain, enhance, and debug.

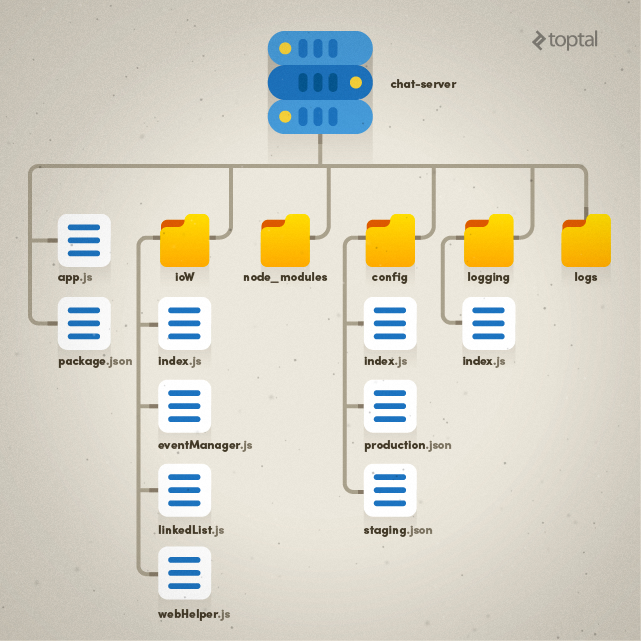

I decided to organize the code into the following architectural components:

- app.js - The entry point for code execution.

- config - The location for all configuration settings.

- ioW - An “IO wrapper” containing all IO and business logic.

- logging - All logging-related code (the directory structure would also include a new

logsfolder for log files). - package.json - The list of package dependencies for Node.js.

- node_modules - All modules required by Node.js.

This organization, while not the only option, struck a balance between clarity and simplicity without excessive complexity.

The resulting directory and file structure is illustrated below:

Enhanced Logging

Logging packages are ubiquitous in modern development environments, so “reinventing the wheel” is rarely necessary.

Working with Node.js, I opted for log4js-node, a version of the log4js library tailored for Node.js. This library offers useful features like logging various message levels (WARNING, ERROR, etc.) and rolling log files that can be split (e.g., daily) to avoid unwieldy, difficult-to-analyze files.

I created a small wrapper around log4js-node to add specific capabilities, choosing to centralize the implementation of extended logging functionality to avoid redundancy and complexity elsewhere in the code.

Dealing with I/O and multiple clients (users) generating multiple connections (sockets), I needed to trace individual user activity in the logs and identify each log entry’s source. This meant having log entries for both application status and specific user actions.

My logging wrapper maps user IDs and sockets, enabling me to track actions before and after an ERROR event. It also allows creating different loggers with contextual information passed to event handlers to identify the log entry’s origin.

The logging wrapper code is available here.

Configuration Management

Supporting different system configurations is often necessary. These differences might involve development versus production environments or even variations based on customer setups and usage scenarios.

Instead of requiring code changes to accommodate these differences, best practice dictates using configuration parameters. In this case, I needed distinct execution environments (staging and production) with potentially different settings. I also wanted to ensure consistent code behavior across these environments. Using a Node.js environment variable, I could specify the appropriate configuration file for a given execution context. I moved all hardcoded configuration parameters to configuration files and created a simple configuration module to load the correct file with the desired settings. Settings were also categorized for organization and easier navigation.

An example configuration file is shown below:

| |

Code Flow

With the folder structure, environment-specific configurations, and logging system in place, let’s examine how these elements connect without modifying business logic.

Thanks to the modular structure, the entry point (app.js) is straightforward, containing only initialization code:

| |

As mentioned earlier, the ioW folder houses business and socket.io-related code, specifically:

index.js- Handles socket.io initialization, connections, event subscriptions, and a centralized error handler for events.eventManager.js- Contains all business logic (event handlers).webHelper.js- Provides helper methods for web requests.linkedList.js- Implements a linked list utility class.

Web request code was refactored into a separate file, while business logic remained untouched.

Important Note: While eventManager.js still contains helper functions that ideally belong in a separate module, extracting them at this stage was deferred to avoid excessive entanglement with business logic.

Node.js’s asynchronous nature often leads to “callback hell,” making code navigation and debugging difficult. To mitigate this, the implementation utilizes promises pattern, specifically leveraging bluebird, a performant promises library. Promises allow for synchronous-like code flow, improved error management, and standardized responses between calls. A key aspect of this implementation is the implicit contract requiring every event handler to return a promise for centralized error handling and logging.

| |

Regarding logging, each connection has a dedicated logger with contextual information. The socket ID and event name are attached to the logger upon creation, ensuring that every log line includes this information:

| |

Another noteworthy point about event handling: The original code had a setInterval call within the socket.io connection event handler, which posed a problem.

| |

This code created a timer at a specified interval (one minute in this case) for every single connection request. With 300 online sockets, for instance, 300 timers would execute every minute. The problem stemmed from the lack of socket usage or any variable scoped within the event handler. The only variable used, messageHub, was declared at the module level, making it shared across all connections. Consequently, separate timers per connection were unnecessary. The code was moved from the connection event handler to the general initialization code (initialize function).

Finally, response processing in webHelper.js was enhanced to handle unrecognized responses by logging relevant information for debugging:

| |

The final step involved setting up a log file for Node.js’s standard error to capture any unhandled errors. On Windows, nssm, a tool with a visual UI, was used to configure a Node.js service with standard output and error files, along with environment variables.

Node.js Performance Considerations

Node.js’s single-threaded nature necessitates strategies for improving scalability. Options include the node cluster module or adding more node processes with nginx for load balancing.

However, in this case, each node cluster subprocess or process would have its own memory space, making information sharing difficult. An external data store like redis would be required to maintain online socket availability across processes.

Conclusion

These steps resulted in a significantly cleaner codebase compared to the original. The focus was not on achieving perfection but on establishing a solid architectural foundation for easier support, maintenance, and debugging.

By adhering to the key software design principles of maintainability, extensibility, modularity, and scalability, the code was transformed into a well-structured, modular system. Issues in the original implementation that contributed to high memory consumption and performance degradation were identified and addressed.

I hope you found this article insightful. Please feel free to share any comments or questions you may have.