Mobile programming inherently involves concurrency and asynchronicity.

Android programming, which usually involves imperative-style programming, can become quite complex when dealing with concurrency. Utilizing Reactive Programming with RxJava can help you circumvent potential concurrency issues by offering a more streamlined and less error-prone approach.

Besides simplifying concurrent, asynchronous tasks, RxJava empowers you to execute functional-style operations that can transform, merge, and collect emissions from an Observable until the desired outcome is reached.

By leveraging RxJava’s reactive paradigm and functional style operations, we gain the ability to model a wide array of concurrency constructs in a reactive manner, even within the non-reactive environment of Android. This article will guide you on how to achieve this. Moreover, you will learn how to integrate RxJava into an existing project incrementally.

If RxJava is a new concept for you, I suggest reviewing the post found here, which covers some of the fundamental aspects of RxJava.

Transitioning from Non-Reactive to the Reactive Realm

Introducing RxJava into your project comes with the challenge of fundamentally altering how you perceive your code.

RxJava necessitates a shift in thinking about data – from being pulled to being pushed. While this concept is straightforward, overhauling an entire codebase built on a pull paradigm can seem overwhelming. Although consistency is optimal, you might not always have the luxury of implementing this transition throughout your entire codebase simultaneously, hence the need for a more incremental approach.

Let’s examine the following code:

| |

This function retrieves a list of User objects from the cache, filters each one based on the presence of a blog, sorts them by username, and finally returns them to the caller. Upon analyzing this snippet, we observe that several of these operations can leverage RxJava operators, such as filter() and sorted().

Rewriting this snippet yields:

| |

The initial line of the function transforms the List<User> returned by UserCache.getAllUsers() into an Observable<User> using fromIterable(). This signifies the first step towards making our code reactive. Now that we are working with an Observable, we can apply any Observable operator provided by the RxJava toolkit – in this case, filter() and sorted().

There are a few other noteworthy points regarding this modification.

Firstly, the method signature has changed. While this might not be significant if the method call is limited to a few locations and changes can be easily propagated up the stack, it becomes problematic if it disrupts clients dependent on this method. In such cases, the method signature should be reverted.

Secondly, RxJava is inherently designed with laziness in mind. This implies that no lengthy operations should be executed until there are subscribers to the Observable. This assumption no longer holds true with this modification, as UserCache.getAllUsers() is invoked even before any subscribers are present.

Departing the Reactive World

To address the first issue arising from our change, we can utilize any of the blocking operators available to an Observable, such as blockingFirst() and blockingNext(). Essentially, both operators block until an item is emitted downstream: blockingFirst() returns the first emitted element and terminates, while blockingNext() returns an Iterable, enabling you to iterate over the underlying data (each iteration of the loop will block).

However, an important side effect of using a blocking operation is that exceptions are thrown on the calling thread instead of being passed to an observer’s onError() method.

Employing a blocking operator to revert the method signature back to List<User>, our snippet would resemble this:

| |

Before invoking a blocking operator (i.e., blockingGet()), we first need to chain the aggregate operator toList(). This modifies the stream from an Observable<User> to a Single<List<User>> (a Single is a specialized Observable that emits a single value in onSuccess() or an error via onError()).

Subsequently, we can call the blocking operator blockingGet(), which unwraps the Single and returns a List<User>.

Although RxJava supports this approach, it should be avoided whenever possible as it deviates from idiomatic reactive programming. However, blocking operators can serve as a useful initial step to transition out of the reactive world when absolutely necessary.

Embracing the Lazy Approach

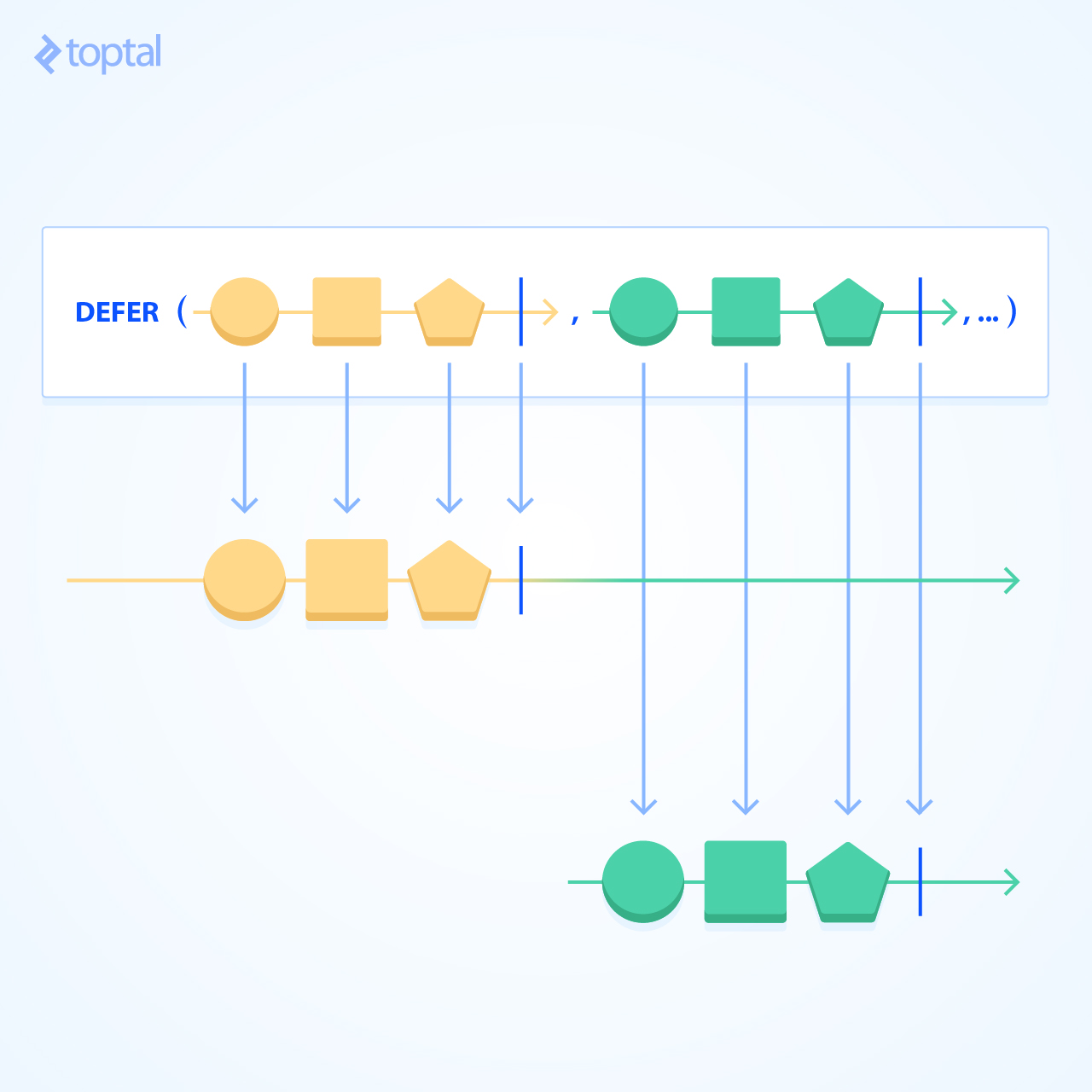

As previously mentioned, RxJava is designed with laziness as a core principle. This means that long-running operations should be postponed for as long as possible, ideally until a subscription is made to an Observable. To achieve laziness in our solution, we employ the defer() operator.

The defer() operator accepts an ObservableSource factory, which generates an Observable for each new observer that subscribes. In our scenario, we want to return Observable.fromIterable(UserCache.getAllUser()) whenever an observer subscribes.

| |

With the long-running operation now encapsulated within a defer(), we have complete control over the thread on which it should execute by simply specifying the appropriate Scheduler in subscribeOn(). This modification makes our code fully reactive, ensuring that subscription occurs only when the data is required.

| |

Another valuable operator for deferring computations is the fromCallable() method. Unlike defer(), which expects an Observable to be returned in the lambda function and subsequently “flattens” the returned Observable, fromCallable() invokes the lambda and returns the value downstream.

| |

Since using fromCallable() on a list would now return an Observable<List<User>>, we need to flatten this list using flatMap().

Towards Reactive-everything

The previous examples demonstrate how we can encapsulate any object within an Observable and seamlessly transition between non-reactive and reactive states using blocking operations and defer()/fromCallable(). By leveraging these constructs, we can begin converting different sections of an Android app to become reactive.

Handling Long Operations

An ideal starting point for incorporating RxJava is whenever you encounter a process that takes a significant amount of time to complete, such as network calls (refer to the previous post for examples), disk reads/writes, and so on. The following example showcases a simple function that writes text to the file system:

| |

When calling this function, we need to ensure that it executes on a separate thread because it is a blocking operation. Imposing such a constraint on the caller adds complexity for the developer, increasing the potential for bugs and potentially hindering development speed.

While adding a comment to the function can help prevent errors by the caller, it is far from foolproof.

However, with RxJava, we can effortlessly encapsulate this operation within an Observable and specify the Scheduler on which it should run. This relieves the caller from the responsibility of invoking the function in a separate thread, as the function handles this internally.

| |

By utilizing fromCallable(), the file writing operation is deferred until subscription time.

Furthermore, because exceptions are treated as first-class objects in RxJava, our modification eliminates the need for a try/catch block. Exceptions are propagated downstream instead of being suppressed, allowing the caller to handle them appropriately (e.g., display an error message to the user based on the specific exception thrown).

Another optimization we can implement is to return a Completable instead of an Observable. A Completable is essentially a specialized type of Observable – similar to a Single – that simply indicates whether a computation succeeded (via onComplete()) or failed (via onError()). Returning a Completable seems more logical in this case, as it seems redundant to return a single true value in an Observable stream.

| |

To complete the operation, we use the fromAction() operation of a Completable because the return value is no longer relevant. Like an Observable, a Completable also supports the fromCallable() and defer() functions if needed.

Replacing Callbacks

Thus far, all the examples we’ve examined either emit a single value (representable as a Single) or indicate the success or failure of an operation (representable as a Completable).

But how do we transform areas in our app that receive continuous updates or events, such as location updates, view click events, sensor events, and so on?

We’ll explore two methods to achieve this: using create() and using Subjects.

create() allows us to explicitly invoke an observer’s onNext() | onComplete() | onError() method as updates are received from our data source. To utilize create(), we pass in an ObservableOnSubscribe that receives an ObservableEmitter whenever an observer subscribes. We can then use this emitter to perform any necessary setup calls to start receiving updates and invoke the appropriate Emitter event.

In the context of location updates, we can register to receive updates within this method and emit location updates as they arrive.

| |

The function within the create() call requests location updates and provides a callback that is invoked when the device’s location changes. As shown here, we essentially replace the callback-style interface and instead emit the received location in the created Observable stream (for brevity, I have omitted some details regarding the construction of a location request; for a deeper dive, you can refer to here).

An important point to note about create() is that each time subscribe() is called, a new emitter is provided. In other words, create() returns a cold Observable. Consequently, in the function above, we could potentially be requesting location updates multiple times, which is undesirable.

To work around this, we want to modify the function to return a hot Observable with the help of Subjects.

Introducing Subjects

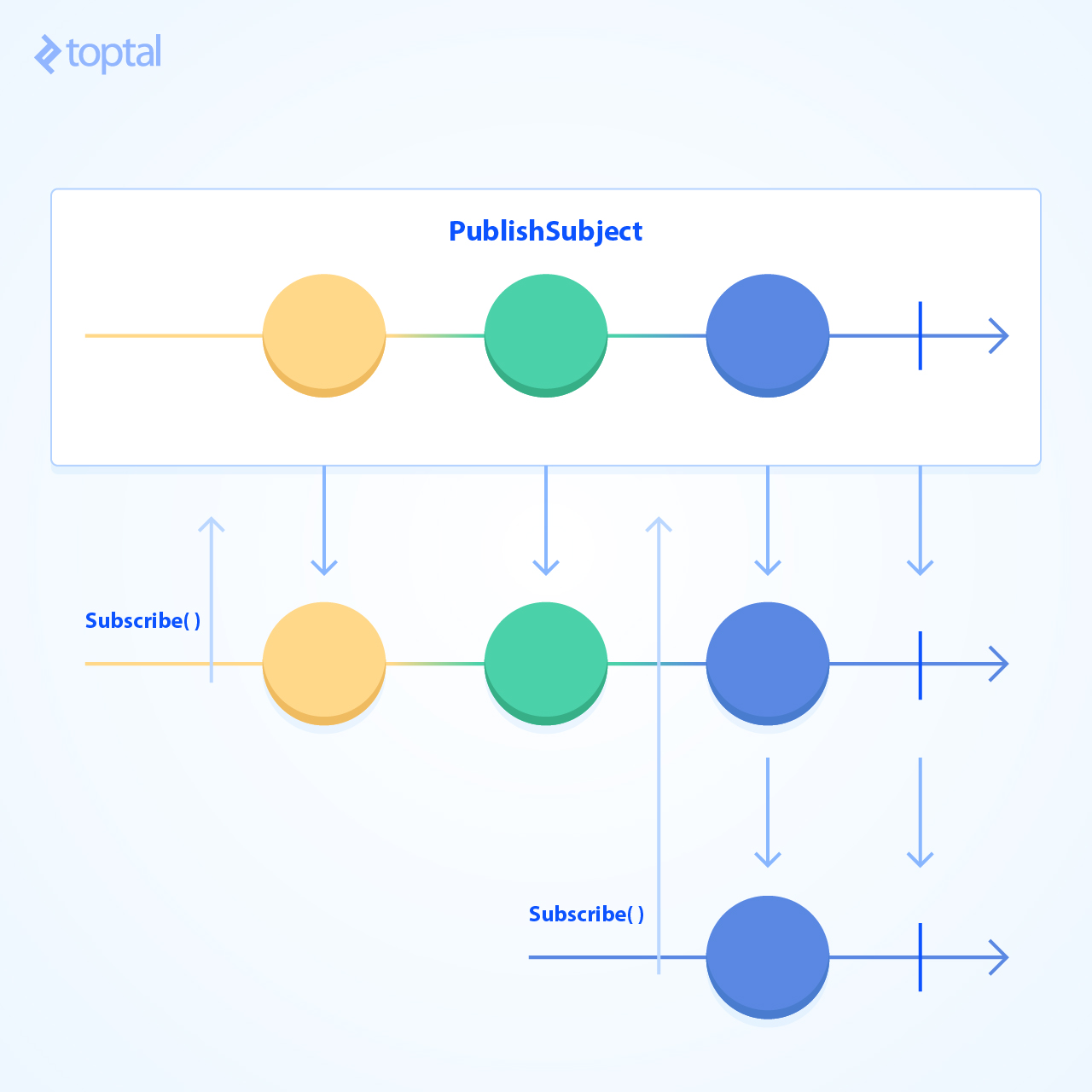

A Subject is an entity that extends an Observable and implements the Observer interface simultaneously. This proves particularly beneficial when we need to emit or broadcast the same event to multiple subscribers concurrently. In terms of implementation, we would expose the Subject as an Observable to clients while maintaining it as a Subject for the provider.

| |

In this new implementation, we employ the PublishSubject subtype, which emits events as they arrive, starting from the time of subscription. Therefore, if a subscription occurs after location updates have already been emitted, the observer will not receive the past emissions, only subsequent ones. If this behavior is not desired, RxJava provides other Subject subtypes that can be used.

Additionally, we have created a separate connect() function that initiates the request to receive location updates. Although the observeLocation() function could still handle the connect() call, we have refactored it out for clarity and simplicity.

In Conclusion

We have explored various mechanisms and techniques:

defer()and its variants to postpone computation execution until subscription.- Cold

Observablesgenerated usingcreate(). - Hot

ObservablesusingSubjects. blockingXoperations for transitioning out of the reactive world.

Hopefully, the examples presented in this article have sparked some ideas regarding different areas within your app that can benefit from a reactive approach. We have covered a lot of ground. If you have any questions, suggestions, or anything that requires clarification, please feel free to leave a comment below!

For those eager to delve deeper into RxJava, I am currently working on a comprehensive book that explains how to approach problems from a reactive perspective using Android examples. If you are interested in receiving updates, please subscribe here.