The landscape of web applications has undergone a dramatic transformation over the past ten years. These applications, once simple platforms for hosting contact forms and basic polls, have evolved into sophisticated software solutions comparable in scale and capability to robust desktop applications. As complexity increases and feature-rich applications become more prevalent, ensuring the security of all application components demands significant time and attention. The remarkable growth in internet users has further emphasized the critical need to safeguard both user data and the applications themselves. A vast array of threats constantly seeks to infiltrate systems, posing significant challenges to all stakeholders.

Established in 2001, the Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) emerged with the mission to combat security vulnerabilities affecting websites and applications. Today, OWASP provides valuable resources, organizes conferences, and establishes standards for web and application security. The OWASP Top Ten Project, a de facto standard for web application security, identifies the ten most critical security risks. This list is compiled based on extensive data analysis and community feedback. A significant update to the project occurred in late 2017, introducing several new threats crucial to modern web applications while retiring others.

This article serves as a companion to the official OWASP Top Ten list, highlighting the recent revisions and providing insights into the evolving threat landscape. It explores the identified threats, offers clear examples for better comprehension, and proposes effective mitigation strategies.

Departures from the OWASP Top 10

The 2013 list served as the most recent iteration until the 2017 update. Considering the significant changes in how web applications are developed and used, a comprehensive revision was necessary. The rise of microservices and the adoption of new frameworks have led to the removal of certain threats and the inclusion of new ones.

This article revisits those previously listed threats while introducing the emerging risks. Understanding the past is crucial to avoid repeating the same mistakes.

Cross-site Request Forgery

Cross-site request forgery (CSRF) is one vulnerability that lost its place in the recent update. Its removal can be attributed to the widespread adoption of modern web frameworks that incorporate CSRF defense mechanisms. Consequently, the likelihood of applications being susceptible to CSRF attacks has significantly decreased.

Despite its absence from the list, it remains prudent to review CSRF to prevent its resurgence.

Essentially, CSRF is an attack that operates like a smoke bomb. Attackers deceive unsuspecting users into executing unintended actions within a web application. They compel victims to send requests to a third-party application without their knowledge. These requests can range from harmless HTTP GET requests for retrieving resources to more detrimental HTTP POST requests that modify resources under the victim’s control. Victims often remain oblivious to these background activities until the damage is done.

Successful user authentication within the targeted application is key to this attack’s effectiveness. If a user had previously logged into an application, the application would have issued a cookie to remember their credentials. When the malicious request is sent, the browser automatically includes this cookie along with any payload, granting the attacker unauthorized access.

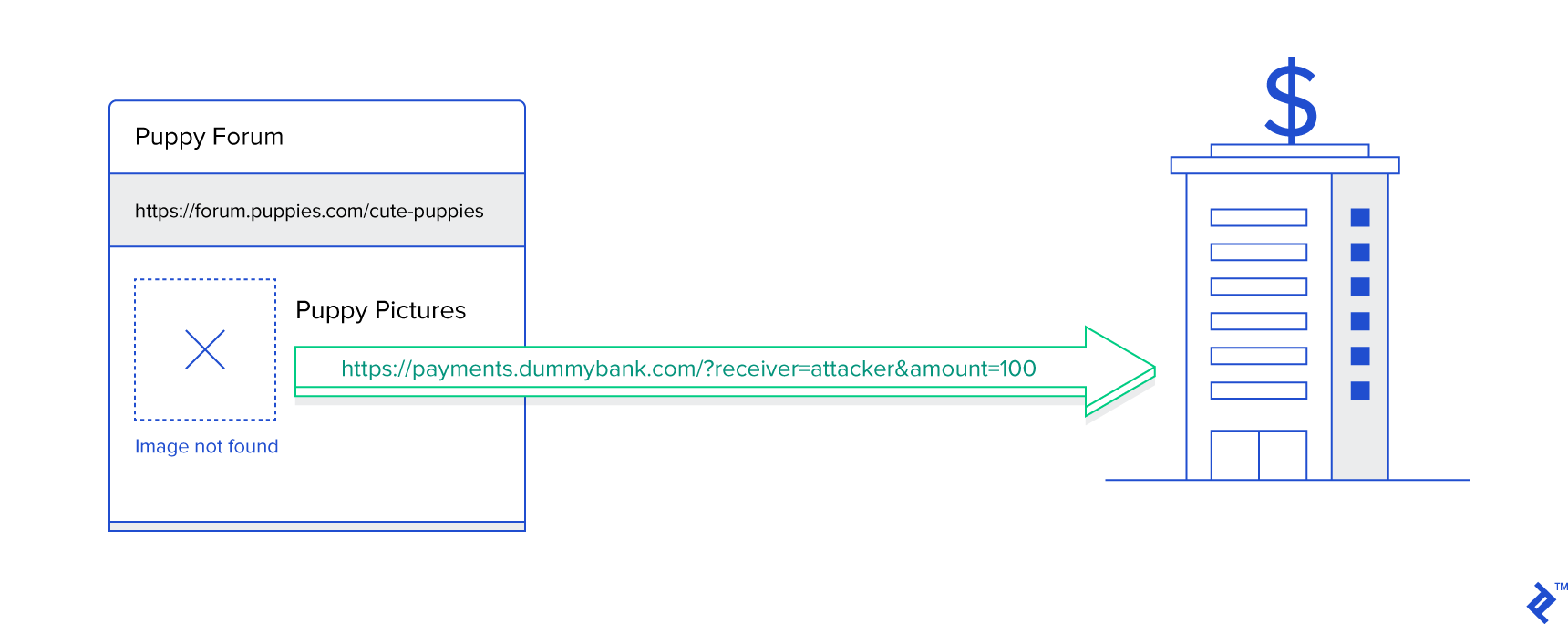

A classic example involves tricking users into transferring funds from their accounts to one controlled by the attacker. Imagine a user logged into their online banking platform to check their balance. Later, they visit an online forum to read reviews of a new mobile phone. An attacker, lying in wait, posts a review with an image containing a seemingly broken hyperlink. This hyperlink, however, points to the e-banking system’s internal URL used for transferring funds: https://payments.dummybank.com?receiver=attacker&amount=100. The banking system identifies the authenticated user as the sender and uses the value from the “receiver” parameter as the recipient. The attacker, of course, sets their own account as the recipient.

Since browsers automatically load images when rendering pages, this request occurs silently in the background. If the bank’s payment system processes money transfers using HTTP GET requests, nothing can prevent the attack from succeeding. While this example is simplified, and most transfers wouldn’t rely on HTTP GET, attackers could, with slightly more effort, manipulate the “action” attribute in the forum’s HTML message posting form. This manipulation redirects the request to the bank’s payment system instead of the intended forum backend.

Financial theft is just one example. Attackers can exploit CSRF to change users’ email addresses or make unauthorized purchases. As is often the case, a combination of social engineering and technical knowledge can exploit software vulnerabilities.

Consider the following when designing your systems:

- Avoid using HTTP GET requests for actions that modify resources. Reserve these requests for retrieving information. A good rule of thumb is to ensure GET requests are idempotent.

- When transmitting data internally using HTTP POST requests, prioritize formats like JSON or XML over encoding parameters as query strings. Using non-trivial data formats reduces the risk of attackers crafting fake HTML forms that target your service.

- Always generate and include unique, unpredictable tokens in your HTML forms. These tokens should be one-time use and unique for each request. Verifying the presence and validity of these tokens mitigates CSRF risks. Attackers would need to compromise your system to obtain valid tokens, rendering them useless after a single use.

The impact of CSRF is amplified when combined with cross-site scripting (XSS). If attackers can inject malicious code into popular websites or applications, the attack’s scope and severity increase significantly. Additionally, XSS vulnerabilities can be leveraged to bypass CSRF protection mechanisms.

Remember, CSRF hasn’t disappeared entirely; it’s just less prevalent.

Unvalidated Redirects and Forwards

Many applications redirect or forward users to different sections within the application or even to external sites after completing an action. For instance, successful logins often trigger redirects to the home page or the page the user initially attempted to access. The destination is frequently embedded in the form’s action attribute or link address. Unvalidated redirects and forwards vulnerabilities arise when the component handling the redirect or forward fails to ensure that the destination address is legitimate.

The primary concerns with unvalidated redirects and forwards are phishing and credential hijacking. Attackers can alter the redirect/forward target to direct users to malicious websites disguised as the original. Unsuspecting users might then unknowingly reveal their credentials and confidential information to these malicious third parties.

Consider an example where a web application implements a login feature with a redirect to the last visited page. The HTML form’s action attribute might resemble: http://myapp.example.com/signin?url=http://myapp.example.com/puppies. Imagine you’re an avid puppy enthusiast who installed a browser extension to replace website favicons with puppy thumbnails. Unfortunately, in this digital age, even puppy love can be exploited. The extension’s developer, sensing an opportunity, introduces a malicious “feature.” Whenever you visit your favorite puppy website, this extension alters the “url” parameter in the form’s action attribute, redirecting you to a different site under their control. This site, designed to mimic the original, tricks you into providing your credit card details to purchase puppy playing cards, effectively funding the attacker’s malicious activities.

Addressing this vulnerability involves validating the destination location to confirm its legitimacy. If a framework or library manages the redirect/forward logic, it’s crucial to review and update the implementation if necessary. Otherwise, manual checks are required to prevent such attacks.

Several types of checks can be implemented. For robust protection, consider a multi-layered approach instead of relying on a single method:

- Validate the outgoing URL, ensuring it points to your domain.

- Instead of using explicit addresses, encode them on the front end and decode and validate them on the back end.

- Maintain a whitelist of trusted URLs, allowing redirects and forwards only to those locations. This approach is generally more effective than maintaining a blacklist, as blacklists are often updated reactively after an incident.

- Consider a technique employed by platforms like LinkedIn, where users are presented with a confirmation page before being redirected, explicitly stating that they are leaving the application.

Merged Issues

Many vulnerabilities on the OWASP list stem from implementation flaws, often due to a lack of knowledge or inadequate consideration of potential threats. These factors can be attributed to a lack of experience, and the solution is straightforward: prioritize continuous learning and thoroughness. One particularly challenging vulnerability, “broken access control,” arises from the human tendency to make assumptions coupled with the inherent complexity of developing and maintaining software systems.

Broken Access Control

This vulnerability arises from inadequate or absent authorization and access control mechanisms within specific parts of an application. Previous iterations of the OWASP Top Ten Project listed two distinct but related issues: insecure direct object references and missing function-level access control. These have been merged into a single category due to their similarities.

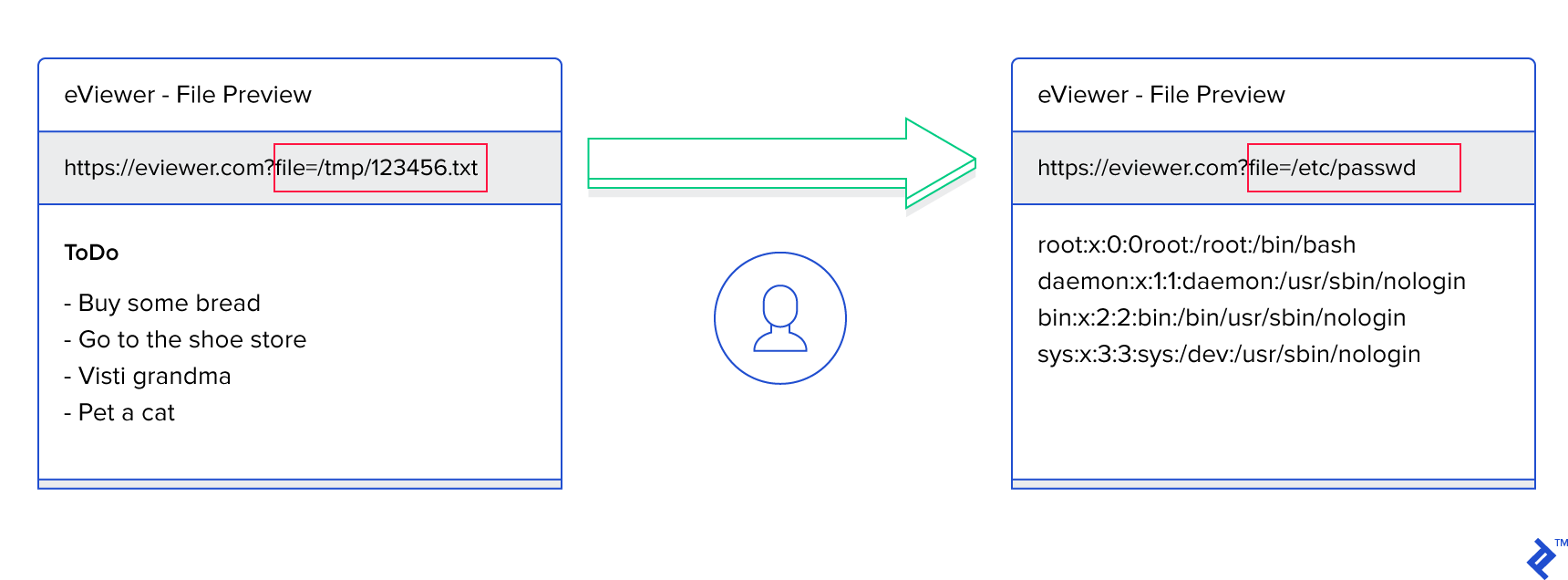

Direct Object References

Direct object references are commonly used in URLs to identify resources being accessed. For example, after logging in, users might access their profiles by clicking a link containing their unique profile identifier. If this identifier is stored in the database and used for retrieving profile information, and the application assumes that the profile page is only accessible after login, then changing the profile identifier in the URL could expose another user’s information.

Consider an application with a delete profile form URL structured as follows: http://myapp.example.com/users/15/delete. This structure reveals that there are at least 14 other users within the application. Determining how to access the delete form for other users wouldn’t be difficult in this scenario.

To mitigate this issue, perform authorization checks for each resource without assuming that users can only reach certain parts of the application through specific paths. Additionally, replace direct references with indirect ones to make it harder for malicious actors to decipher how references are generated.

As a precautionary measure during development, create a simple state machine diagram. Represent different pages within your application as states and user actions as transitions. This visualization helps you identify all transitions and pages that require particular attention.

Missing Function-level Access Control

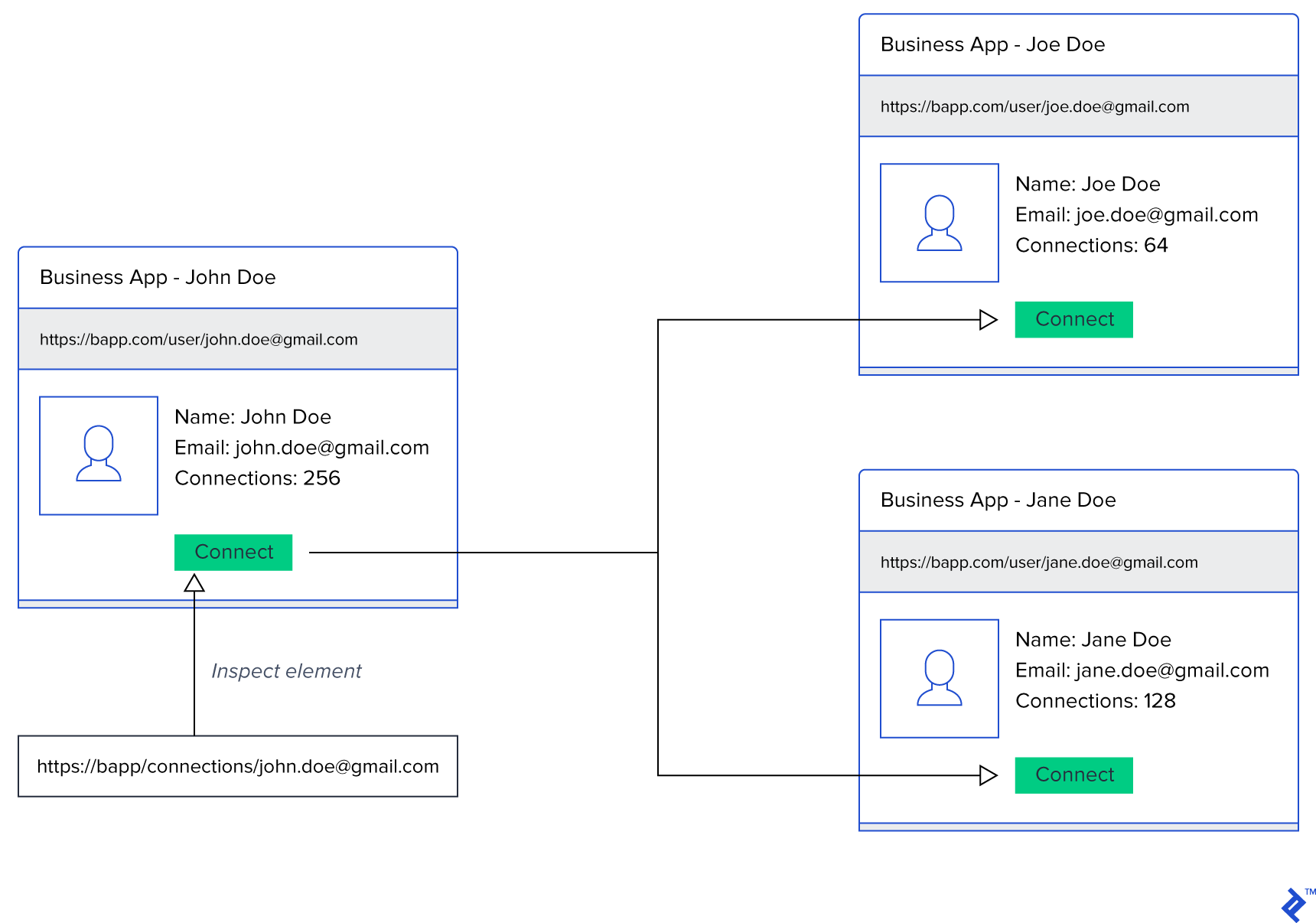

This vulnerability closely resembles insecure direct object references. Attackers modify the URL or parameters to gain unauthorized access to protected areas of the application. Without proper access control mechanisms in place, they can gain privileged access to application resources or at least obtain information about their existence.

Expanding on the previous example, if an application assumes that a user accessing the delete form is a superuser simply because superusers can see the link to that form, without any additional authorization, a significant security flaw is introduced. Relying on the presence or absence of UI elements for access control is insufficient.

The solution lies in implementing robust access control checks across all layers of your application. The front-end interface is not the only avenue through which attackers can target your domain layer. Additionally, avoid solely relying on user-provided information about their access levels. Implement proper session management and always verify received data. Never assume a user’s role based solely on the request body.

The “broken access control” category now encompasses all issues related to insufficient access control, spanning both the application and system levels, such as file system misconfigurations.

New Entrants to the OWASP Top 10

The emergence of new front-end frameworks and the adoption of modern software development practices have shifted security concerns to new areas. While new technologies have automated solutions to previously manual tasks, they have also introduced new vulnerabilities, necessitating a reassessment and update of the OWASP Top Ten list to reflect these changes.

XML External Entities

The XML standard includes a lesser-known feature called an external entity, which is part of the document’s data type definition (DTD). This feature allows document authors to specify links to external entities that can be referenced and included within the main document. Here’s a simple example:

| |

During parsing, the reference &bar; is replaced with the content from the defined entity, resulting in <foo>baz</foo>.

If an application were to accept external input and incorporate it directly into the XML document definition without proper validation, it would open the door to data leaks and various attacks.

What makes this vulnerability particularly potent is that the entity doesn’t have to be a simple string; it can reference a file on the file system. The XML parser would then readily include the contents of that file in the generated response, potentially exposing sensitive system information. OWASP illustrates how easily an attacker could obtain information about system users by defining the entity as follows:

| |

One particularly concerning aspect of this vulnerability is the ease with which it enables denial-of-service attacks. One method involves referencing an infinitely large file like /dev/random. Another involves creating a chain of entities, each referencing the previous one multiple times. This creates a deeply nested tree structure, and the parsing process can consume excessive system resources, potentially leading to a crash. This attack is known as the Billion Laughs attack. As demonstrated on Wikipedia, a series of seemingly harmless entities can be defined to inject billions of “lol” strings into the final document.

| |

Mitigating XML external entity exploits involves adopting less complex data formats like JSON, although even JSON requires precautions due to potential vulnerabilities. Additionally, keeping XML libraries up to date, disabling external entity processing and DTDs, and diligently validating and sanitizing data from untrusted sources before use or inclusion in documents are crucial steps.

Insecure Deserialization

Developers wield significant control over the systems they build through code. But imagine the potential if one could influence the behavior of third-party systems with minimal or even no code. Due to human fallibility and software vulnerabilities, this is a real possibility.

Applications often serialize and store their state and configuration data. In some cases, browsers act as storage mechanisms if the serialized data is tied to the current user. An application, in an attempt to optimize performance, might use a cookie to indicate that a user is logged in. Since the cookie can only be created after successful authentication, storing the username within the cookie might seem reasonable. The presence and content of this cookie then dictate authentication and authorization. In an ideal world, this approach wouldn’t pose any issues. However, curiosity and malicious intent are inherent human traits.

A curious user, upon discovering this cookie on their machine, might encounter something like this:

| |

This appears to be a standard Python dictionary serialized into JSON. However, an even more inquisitive user might attempt to modify the expiration date to bypass the application’s session timeout. A truly determined individual might even change the username to "jane.doe". If such a username existed within the system, it would grant unauthorized access to private data.

This simple example of serializing data into JSON barely scratches the surface of potential vulnerabilities. Attackers who successfully manipulate serialized data can potentially execute arbitrary code on the target system.

Consider a scenario where you’re building a REST API that allows users to upload and train their own machine learning models written in Python. Your service evaluates these models and trains them using your datasets, providing users with access to your computing resources and extensive datasets.

Instead of storing the code in plain text, users pickle their code, encrypt it using their private key, and submit it to your API for training. When your service needs to execute a model, it decrypts the code, deserializes it, and runs it. The problem lies in the inherent insecurity of the pickle protocol. Maliciously crafted code can exploit the deserialization process to execute arbitrary code.

Python’s pickle protocol allows classes to define a method called __reduce__. This method provides instructions on how to deserialize a custom object. One possible return value is a tuple containing a callable and a tuple of arguments for that callable. Given that your ML model training system aims for flexibility in code structure, an attacker could write the following code:

| |

When this object needs to be deserialized, the list function is called with a single argument. In Python, list is the list constructor, and itertools.count generates an infinite iterator. Attempting to convert this infinite iterator into a finite list can lead to disastrous consequences for your system’s performance and stability.

The most effective way to mitigate this vulnerability is to avoid deserializing data from external sources altogether. If this isn’t feasible, consider using checksums or digital signatures to verify the integrity of the data and ensure it hasn’t been tampered with. Additionally, running deserialization within a sandbox environment isolated from your main system can limit the impact of potential exploits.

When relying on external libraries for deserializing data formats like XML or JSON, opt for those that allow object type checks before the actual deserialization process. This can help identify unexpected object types that might be malicious.

As with all critical operations, implement comprehensive logging and monitoring. Frequent deserialization attempts or an unusual number of failures could indicate malicious activity. Early detection is paramount.

Insufficient Logging and Monitoring

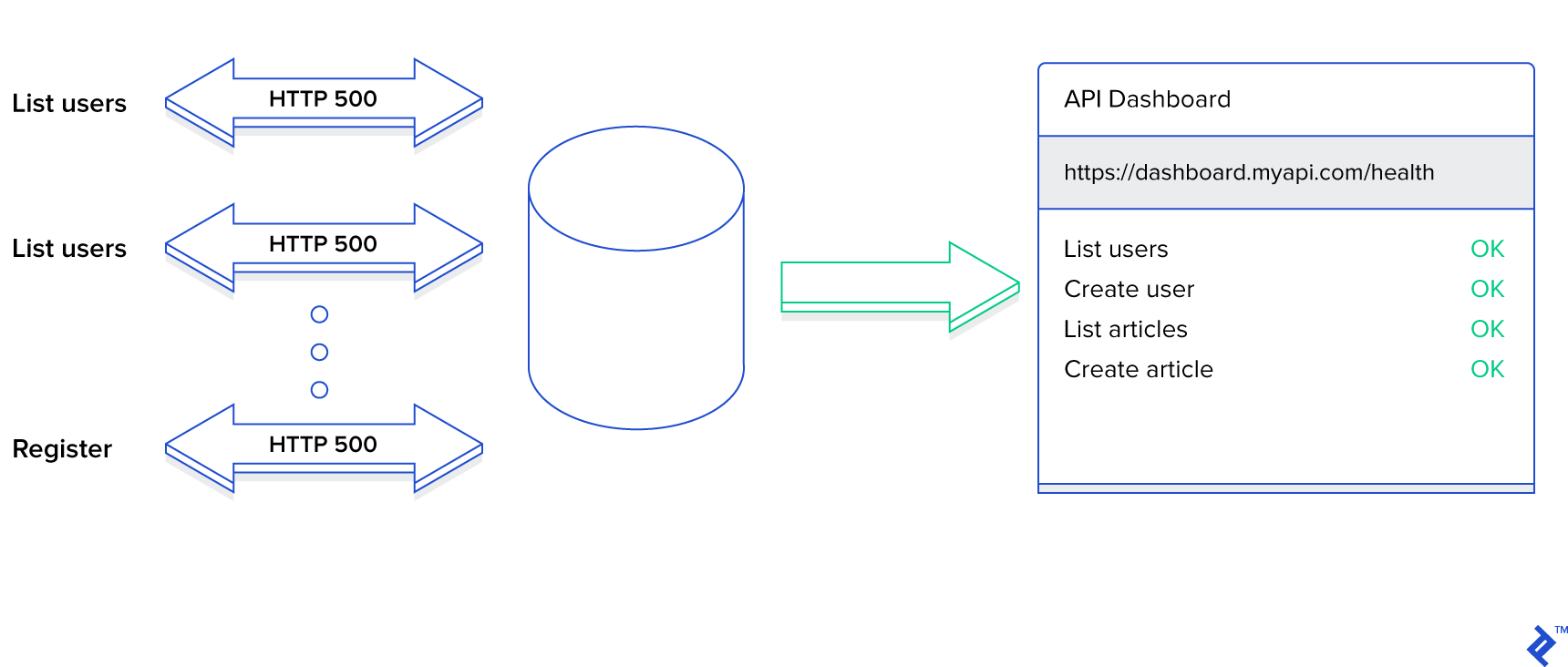

How much effort do you dedicate to ensuring that all warnings and errors within your application are logged appropriately? Do you log only code-level errors, or do you also track validation errors and violations of your domain’s business rules? Failure to record all suspicious and erroneous activities creates vulnerabilities that attackers can exploit.

Consider a scenario where your application, like many others, has a login page with fields for email and password. A user attempting to log in with an incorrect password is allowed to retry. However, there’s no limit on the number of incorrect attempts, meaning the login page won’t lock after a certain threshold. An attacker could exploit this by using a rainbow table to try different password combinations against a known email address until they successfully gain access. While robust password hashing can mitigate this specific attack, do you have mechanisms in place to detect such intrusion attempts?

Even if this particular attack fails, it doesn’t guarantee that others won’t succeed. The login page is unlikely to be the only potential entry point for attackers. Exploiting broken access controls is another possibility. Even well-designed applications can be targeted, and detecting these attempts is crucial.

To bolster your defenses against such attacks, consider the following measures:

- Log all failures and warnings within your application, encompassing code-level exceptions, access control violations, validation errors, and data manipulation issues. Replicate and persist this information for an extended period to facilitate retrospective analysis and auditing.

- Choose a suitable format and persistence layer for your logs. A large text file might be easy to create but difficult to process. Opt for storage solutions that allow for easy data retrieval and formats that support efficient serialization and deserialization. Storing JSON data in a database that enables fast querying simplifies analysis. Regularly back up and archive this database to manage its size.

- For sensitive and valuable data, maintain an audit trail that records all actions performed, enabling you to trace back to the origin of any changes. Implement mechanisms to prevent data tampering.

- Employ background processes to analyze logs and raise alerts for suspicious patterns. Simple checks, such as identifying repeated attempts to access protected resources, can be highly effective. However, avoid overloading the system with excessive checks, as this can impact performance. Run monitoring systems as separate services to minimize impact on the main application.

When addressing this vulnerability, prioritize preventing error logs from being exposed to external users. Leaking such information can provide attackers with valuable insights into your system’s vulnerabilities. Logging and monitoring should serve as tools for maintaining security, not aids for attackers.

The Road Ahead

Awareness of potential threats and vulnerabilities in web applications is paramount. More importantly, actively identifying and addressing these issues within your applications is essential.

Prioritizing application security should be an integral part of every stage of the software development lifecycle. Software architects, developers, and testers must incorporate security testing procedures into their workflows. Leverage security checklists and automated tests at appropriate stages to minimize security risks.

Whether analyzing an existing application or building a new one, familiarize yourself with the OWASP Application Security Verification Standard Project (ASVS). This project aims to establish a standard for verifying application security. It outlines tests and requirements for developing secure web applications, categorized into three levels based on severity, with level three representing the most critical threats. This classification helps prioritize efforts based on the most likely and impactful risks. Not every application requires every test outlined in the ASVS.

Both new and existing web application projects, particularly those adhering to Agile principles, benefit from structured planning for security testing. The OWASP Security Knowledge Framework simplifies the planning process for OWASP ASVS tests. This application helps manage security-focused sprints, provides examples of common security problem solutions, and offers easy-to-follow checklists based on the ASVS.

If you’re new to web application security and seeking a safe environment to experiment, explore OWASP’s intentionally insecure web application: WebGoat. This application provides guided lessons, each focusing on a specific security threat.

During application development, prioritize the following:

- Threat identification and prioritization: Identify realistic threats relevant to your application and assess their potential impact. Prioritize these threats to determine which deserve the most attention during development and testing. For instance, investing significant effort in sophisticated logging and monitoring might be overkill for a static blog.

- Architectural and design review: Addressing certain vulnerabilities becomes significantly more challenging in later stages of development. If your application relies on executing third-party code and lacks a sandbox environment, defending against insecure deserialization and injection attacks becomes a substantial undertaking.

- Development process enhancement: Integrate automated security testing into your workflows as much as possible. Enhance your CI/CD pipelines with automated tests designed to identify security flaws. You can even leverage existing unit testing frameworks to develop and periodically run security tests.

- Continuous learning and improvement: The landscape of security vulnerabilities is constantly evolving, extending far beyond the ten or fifteen listed here. New features and technologies inevitably introduce new attack vectors. Staying informed about the latest trends in web application security is crucial. However, knowledge without application is futile.

Conclusion

While the OWASP Top Ten Project highlights ten significant security vulnerabilities, countless other traps and backdoors threaten your applications, your users, and their data. Remain vigilant and prioritize continuous learning, as technological advancements bring both benefits and risks.

Furthermore, recognize that security vulnerabilities seldom exist in isolation. Exposure to one often indicates the presence of others lurking nearby, waiting for an opportunity to surface. And even if a vulnerability isn’t directly your fault as a security-conscious developer, you are still responsible for mitigating risks and protecting your users. A prime example of this interconnectedness is highlighted in the article Hacked Credit Card Numbers Are Still, Still Google-able.