Aside from its enhanced admirable performance improvements, Vue 3 offers a suite of new features, with the Composition API arguably taking center stage. This article is split into two parts. We’ll start by revisiting the need for this new API: achieving superior code organization and reusability. Subsequently, we’ll delve into less-explored facets of the API, such as constructing reactivity-driven functionalities that were previously unattainable within Vue 2’s reactivity system.

We’ll refer to this newfound capability as on-demand reactivity. After introducing the relevant Vue 3 features, a simple spreadsheet application will be built, demonstrating the enhanced expressiveness of Vue’s reactivity system. Lastly, we’ll examine potential real-world applications for this improved on-demand reactivity.

Vue 3’s New Additions and Their Significance

Vue 3](https://v3.vuejs.org/) constitutes a [major rewrite of Vue 2, introducing a plethora of improvements while retaining backward compatibility with the old API almost in its entirety.

The Composition API stands out as one of the most significant additions to Vue 3. Its initial public reveal ignited considerable controversy. For those unfamiliar with this new API, let’s first understand its rationale.

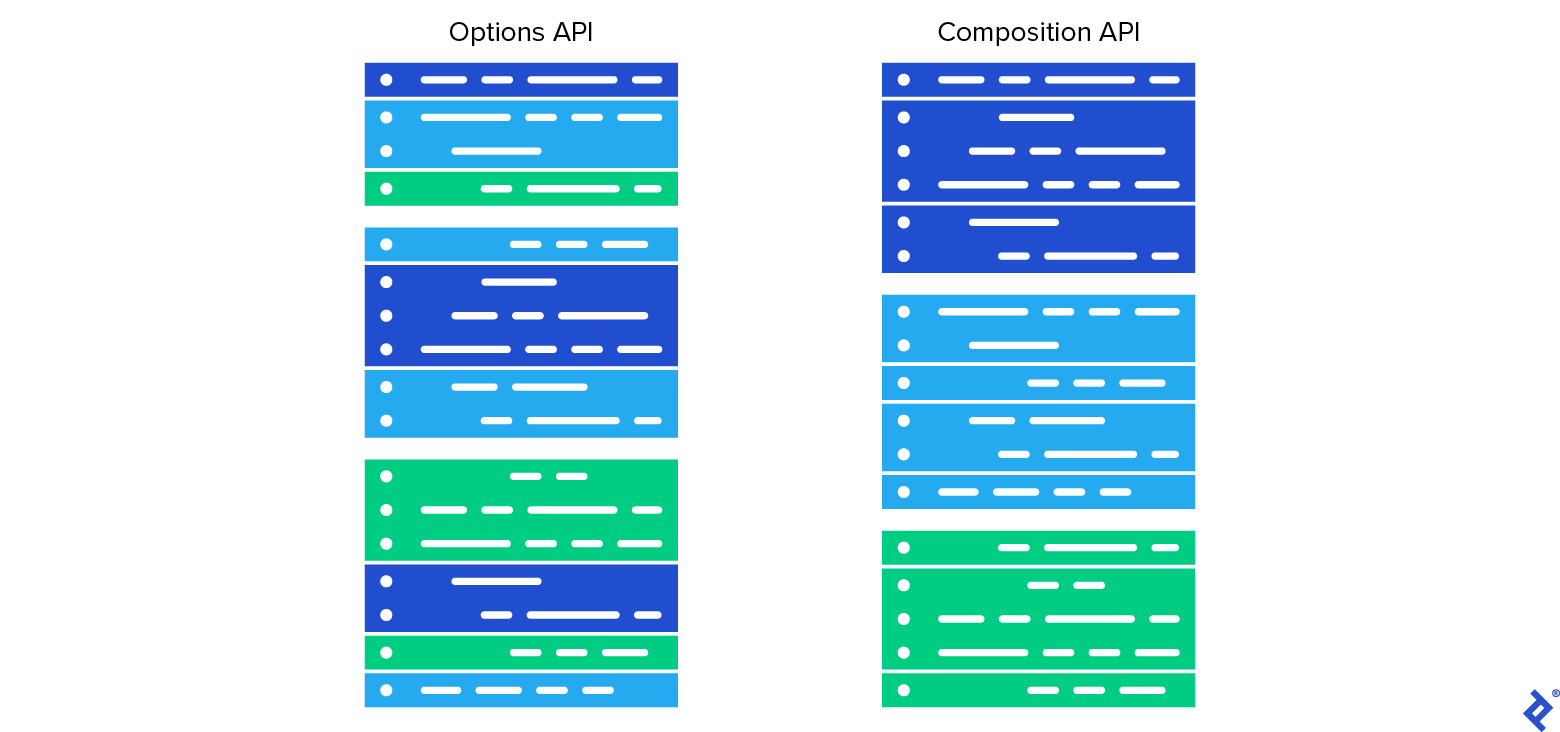

In Vue, code is typically organized within a JavaScript object. This object utilizes keys to represent various aspects of a component. You’ll find sections for reactive data (data), computed properties (computed), component methods (methods), and more.

This paradigm, however, can lead to components with multiple, potentially unrelated functionalities, with their inner workings spread across different component sections. Imagine a component for file uploading that handles both file management and an upload status animation—two largely distinct features.

The <script> portion of this component might look something like this:

| |

This traditional approach has its merits, primarily in simplifying code addition for developers. New reactive variables go in the data section, and when you’re searching for an existing one, you know where to look.

However, this method of dividing functionality into sections like data and computed isn’t always ideal.

Commonly cited drawbacks include:

Component Complexity: Managing components with numerous functionalities becomes challenging. For example, enhancing our animation code to include a delayed start would require navigating between various component sections, especially problematic for large components.

Code Reusability: Reusing a specific combination of reactive data, computed properties, and methods across multiple components becomes cumbersome.

Vue 2 (and Vue 3, for backward compatibility) address most code organization and reuse issues through mixins.

Weighing the Pros and Cons of Mixins in Vue 3

Mixins offer a way to extract and encapsulate component functionalities into separate units of code. Each functionality is housed in its own mixin, and components can utilize one or more of these mixins. The elements defined within a mixin become seamlessly accessible within the component using it. In essence, mixins resemble classes in object-oriented programming, collecting code related to specific functionalities and allowing inheritance-like behavior in other code units.

The challenge with mixins arises from their flexible nature—they aren’t bound by strict encapsulation principles like classes. Mixins can be loose collections of code without a well-defined interface. Consequently, using multiple mixins within a component can lead to code that’s hard to understand and maintain.

Most object-oriented languages like C# and Java, despite having mechanisms to handle complexity, discourage or even disallow multiple inheritance. Even in languages like C++ where it’s permitted, composition is generally favored over inheritance.

A more practical concern with Vue mixins is name collision, occurring when two or more mixins declare the same names. While Vue’s default handling of name collisions can be adjusted by developers, this introduces additional complexity.

Another limitation is the lack of a constructor-like mechanism in mixins. This poses a challenge when near-identical functionality is needed across components. While workarounds using mixin factories exist for simple cases, they have limitations.

Therefore, mixins aren’t a perfect solution for code organization and reuse, their shortcomings becoming more pronounced as project size increases. Vue 3 introduces a new approach to address these challenges.

Composition API: Reshaping Code Organization and Reuse in Vue 3

The Composition API provides a way to completely decouple component elements without making it mandatory. Every piece of code—variables, computed properties, watchers, etc.—can be defined independently.

For instance, instead of an object with a data section containing an animation_state key set to “playing,” we can now write:

| |

The effect is largely the same as declaring this variable in a component’s data section. The key difference is that this externally defined ref needs to be made available to the component intending to use it. This involves importing its module and returning the ref from the component’s setup section. We’ll set this procedure aside for now to focus on the API itself. It’s important to note that reactivity in Vue 3 is independent of components; it’s a self-contained system.

We can use the animation_state variable in any scope where it’s imported. After creating a ref, we use ref.value to get and set its value:

| |

The .value suffix is crucial because without it, we’d be assigning the non-reactive value “paused” directly to the animation_state variable. JavaScript’s reactivity, whether implemented through defineProperty as in Vue 2 or Proxy in Vue 3, requires an object with keys that can be reactively manipulated.

This behavior was also present in Vue 2, where a component prefixed any reactive data member (component.data_member). Until JavaScript allows assignment operator overloading, reactive expressions will necessitate an object and key (like animation_state and value) on the left-hand side of assignments for reactivity.

Within templates, .value can be omitted since Vue preprocesses template code, automatically detecting references:

| |

While the Vue compiler could theoretically preprocess the <script> section of a Single File Component (SFC) to insert .value where needed, this might not be desirable as it would create inconsistencies between SFCs and other code.

When dealing with entities like JavaScript objects or arrays that won’t be completely replaced, and only their keyed fields require modification, a shorthand exists. Using reactive instead of ref eliminates the need for .value:

| |

Decoupled reactivity with ref and reactive isn’t entirely new; it was partially introduced in Vue 2.6 as “observables.” You could largely substitute Vue.observable with reactive. One distinction is that Vue.observable allowed direct reactive access and mutation of the passed object. In contrast, the new API returns a proxy object, so mutating the original object won’t trigger reactive updates.

The significant advancement in Vue 3 is the ability to define other reactive component elements—computed properties, watchers, lifecycle methods, and dependency injections—independently, alongside reactive data.

Computed properties are implemented as expected:

| |

Similarly, various types of watches, lifecycle methods, and dependency injections can be implemented. However, we won’t cover those in detail here.

When using SFCs with Vue 3, even with the traditional API and its separate sections, the Composition API’s reactivity elements are integrated using the new setup section. This section acts like a lifecycle method, executing before any other hook, including created.

Here’s a complete component example combining the traditional approach with the Composition API:

| |

Key takeaways from this example:

setupfor Composition API: All Composition API code is placed within thesetupmethod. You can even create separate files for each functionality, import them into your SFC, and return the required reactive elements fromsetupto make them available.Mixing Approaches: The new and traditional approaches can coexist. Notice that

x, despite being a reference, doesn’t require.valuewithin the template or traditional component sections likecomputed.Multiple Root Nodes: Another new feature in Vue 3 is the ability to have multiple root DOM nodes in templates, as demonstrated in the example.

Unleashing Greater Reactivity Expressiveness in Vue 3

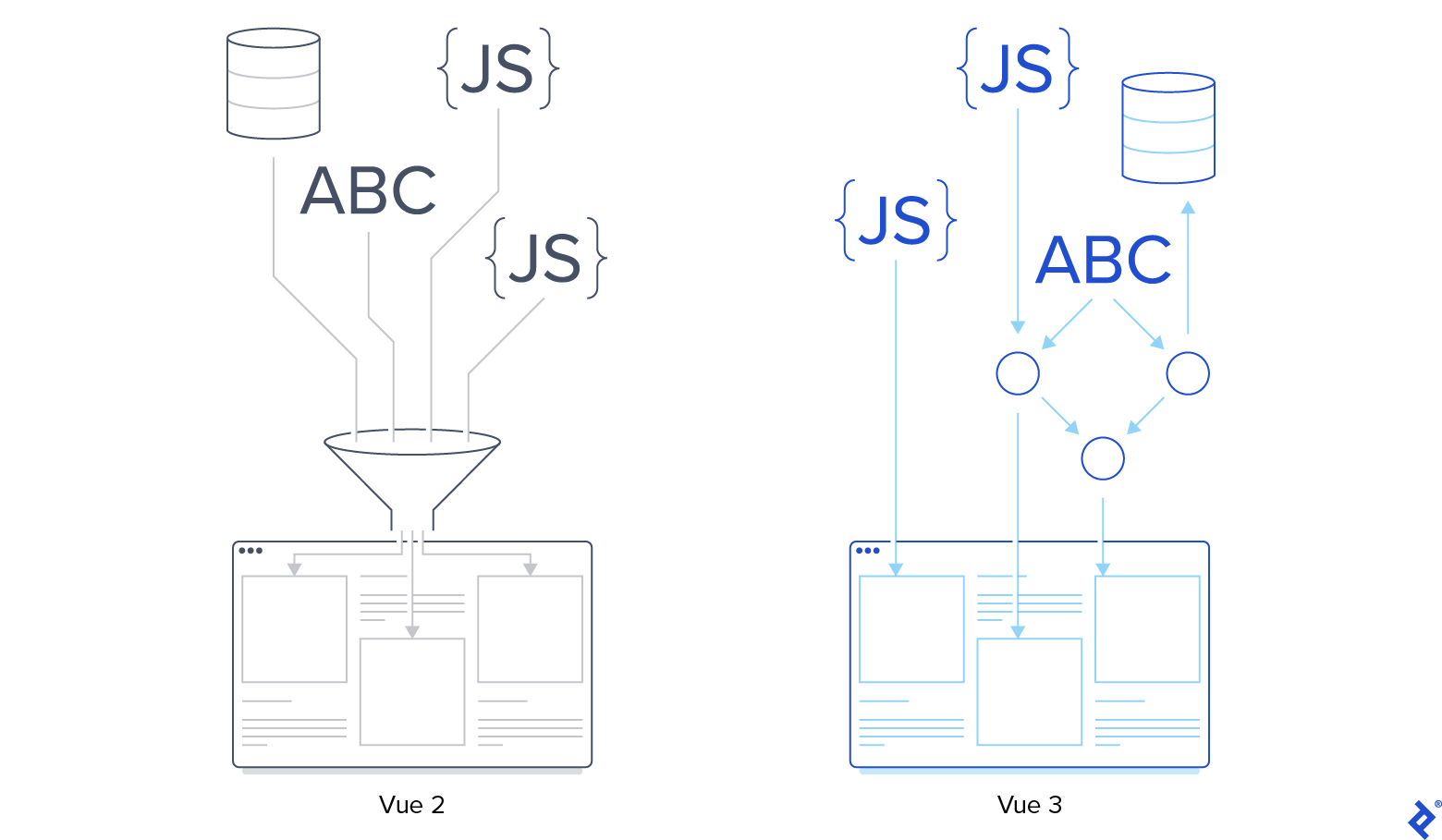

While code organization and reuse are the primary motivators for the Composition API, it offers more than just structural improvements. The ability to dynamically add reactivity unlocks greater potential for creating complex reactive systems, going beyond the capabilities of Vue 2.

Spreadsheet Creation: Comparing Vue 2 and Vue 3

Spreadsheet applications like Excel, Calc, and Google Sheets all rely on some form of reactivity. They present a table where cell content can be a simple value or a formula, essentially a computed property potentially dependent on other values or computed properties. Notably, unlike Vue’s traditional reactivity, these spreadsheets even allow for self-referential computed properties, useful for iterative approximations.

When a cell’s content changes, all dependent cells update, potentially triggering further updates if needed.

Building a spreadsheet with Vue naturally raises the question: can we leverage Vue’s reactivity system? Ideally, we’d store each cell’s raw editable value and its corresponding computed value. Computed values would either mirror the raw value or be the result of the formula entered.

In Vue 2, one approach would involve a raw_values two-dimensional array for raw data and a computed_values (computed) array for calculated values.

For small, fixed-size tables, defining raw and computed values for each cell within the component definition is an option, albeit aesthetically unappealing and impractical for true spreadsheets where cell count isn’t predetermined.

The computed_values array also presents challenges. Computed properties are functions that might need to reference themselves (calculating a cell’s value often requires other computed values). Even if Vue permitted self-referential computed properties, updating a single cell would trigger recalculations for all cells, regardless of dependencies, leading to significant inefficiency. We’d end up using Vue 2’s reactivity only for detecting raw data changes, implementing the rest of the reactivity logic manually.

Vue 3’s Solution for Computed Values

With Vue 3, we can dynamically create a new computed property for each cell as the table grows.

Let’s consider cells A1 and A2, where A2 should display the square of A1 (value: 5):

| |

If we want to change A1 to 6, simply writing:

| |

doesn’t just update the value; it changes the identity of A1 to a new computed property resolving to 6. However, A2 remains linked to the old A1. To resolve this, A2 shouldn’t directly reference A1 but rather an intermediary that always reflects the current value of A1, essentially a pointer. While JavaScript lacks first-class pointers, we can simulate one using an object: pointer = { points_to: value }. Redirecting the pointer involves assigning to pointer.points_to, and dereferencing retrieves pointer.points_to.

Therefore:

| |

Now, we can update the value:

| |

As suggested by redblobgames on Vue’s Discord, an alternative approach is to use references wrapping regular functions instead of computed values. This allows swapping the function without altering the reference’s identity.

Our spreadsheet implementation will reference cells using keys from a two-dimensional array, providing the required level of indirection, eliminating the need for explicit pointer simulation. We could even use a single array for both raw and computed values, treating everything as computed:

| |

However, distinguishing between raw and computed values is preferable. This allows binding raw values to input elements, and computed properties update automatically based on raw data without requiring redefinition.

Constructing the Spreadsheet

Let’s define some basic elements:

| |

Our goal is to calculate computed_values[row][column] based on raw_values[row][column]. If the raw value doesn’t start with =, it’s returned directly. Otherwise, the formula is parsed, compiled into JavaScript, executed, and its result returned. For brevity, we’ll simplify formula parsing and skip optimizations like a compilation cache.

We’ll allow users to input any valid JavaScript expression as a formula, replacing cell references like A1, B5, etc., with references to the actual computed cell values. Assuming cell names are always valid identifiers, the transpile function handles this (assuming single-letter column indices for simplicity):

| |

transpile converts expressions with cell references into pure JavaScript.

Next, we create a factory function to generate computed properties for each cell, executed once per cell:

| |

Within the setup method, we’d return: {raw_values, computed_values, rows, cols, letters, calculations}.

Below is the complete component with a basic user interface:

You can find the code on GitHub, along with a live demo on live demo.

| |

Exploring Real-World Applications

Vue 3’s decoupled reactivity enables not just cleaner code but also more intricate reactive systems. While this level of expressiveness hasn’t been a pressing need in Vue’s seven-year history, our spreadsheet example highlights the possibilities.

You can find the spreadsheet example for a clear demonstration, as well as the live demo.

While this example is relatively niche, on-demand reactivity can be beneficial in complex applications, particularly for performance optimization.

Front-end applications handling large datasets can suffer from poorly implemented reactivity. Consider a business dashboard displaying interactive reports. Users can filter by time range and add/remove performance indicators, some of which might depend on others.

A monolithic approach would involve a single computed property (e.g., report_data) updating whenever users change input parameters. This computed property would then calculate all indicators based on a hardcoded plan, starting with independent ones, then those dependent on them, and so on.

A more efficient solution would decouple report elements and compute them independently. Benefits include:

Automatic Dependency Detection: Developers avoid manually defining a tedious and error-prone execution plan, relying on Vue’s reactivity system.

Performance Gains: By updating only the data affected by user input, substantial performance improvements can be achieved, especially with large datasets.

If all potential report indicators are known upfront, this decoupling could be achieved in Vue 2. However, when dealing with dynamic data sources or external providers, Vue 3’s on-demand computed properties become crucial.

Vue 3 makes this not just possible but also straightforward to implement.