We are constantly bombarded with data. Vast and expanding databases and spreadsheets hold a wealth of concealed business insights. But with such an overwhelming volume, how can we effectively analyze this data and draw meaningful conclusions? Graphs, specifically networks rather than bar graphs, offer a sophisticated solution.

Tables are commonly used for general information representation. However, graphs employ a unique data structure. Instead of rows in a table, nodes represent elements, and edges connect these nodes to illustrate their relationships.

This graph data structure allows us to view data from novel perspectives. This is why graph data science is utilized across diverse fields, spanning from molecular biology to the social sciences:

Right image credit: ALBANESE, Federico, et al. “Predicting Shifting Individuals Using Text Mining and Graph Machine Learning on Twitter.” (August 24, 2020): arXiv:2008.10749 [cs.SI]

So, how can developers effectively leverage graph data science? The answer lies in the versatile most-used data science programming language: Python.

A Beginner’s Guide to “Graph Theory” Graphs in Python

Python developers have access to a variety of graph data libraries, such as NetworkX, igraph, SNAP, and graph-tool. Despite their individual pros and cons, they share remarkably similar interfaces for Python graph visualization and structural manipulation.

For our purposes, we’ll be utilizing the widely-used NetworkX library. Its ease of installation and use, coupled with its support for the community detection algorithm we’ll be employing, make it an excellent choice.

Creating a new NetworkX graph is remarkably simple:

| |

However, without any nodes or edges, G isn’t much of a graph yet.

Incorporating Nodes into a Graph

Adding a node to the network is as simple as chaining the return value of Graph() with .add_node() (or .add_nodes_from() to add multiple nodes from a list). Additionally, we can assign arbitrary characteristics or attributes to the nodes by passing a dictionary as a parameter, as demonstrated with node 4 and node 5:

| |

This will yield the following output:

| |

However, without edges connecting the nodes, they remain isolated, and the dataset is no more informative than a basic table.

Establishing Connections: Adding Edges to a Graph

Similar to adding nodes, we can use .add_edge() with the names of two nodes as parameters (or .add_edges_from() for multiple edges in a list). Optionally, we can include a dictionary of attributes:

| |

The NetworkX library accommodates graphs like these, where each edge can have an associated weight. For instance, in a social network graph where nodes represent users and edges signify interactions, weight could indicate the frequency of interactions between a specific pair of users—a highly pertinent metric.

While NetworkX lists all edges when using G.edges, it doesn’t include their attributes. To retrieve edge attributes, we can use G[node_name] to access everything connected to a specific node or G[node_name][connected_node_name] to obtain the attributes of a particular edge:

| |

This will produce the following output:

| |

However, interpreting our first graph in this manner is impractical. Fortunately, there’s a much more effective representation.

From Graphs to Images: Generating Visualizations (Including Weighted Graphs)

Visualizing a graph is crucial. It provides a rapid and clear understanding of the relationships between nodes and the overall network structure.

A simple call to nx.draw(G) is all it takes:

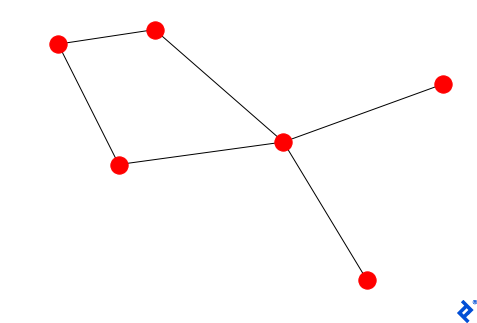

Let’s enhance this by making edges with greater weight proportionally thicker through our nx.draw() call:

| |

We’ve set a default thickness for edges without weight, as evident in the result:

As our methods and graph algorithms become more intricate, we’ll transition to a more familiar dataset for our next NetworkX/Python illustration.

Graph Data Science in Action: Exploring Data From the Movie Star Wars: Episode IV

To enhance interpretability and comprehension, we’ll be utilizing data from this dataset. In this dataset, nodes represent significant characters, and edges (unweighted in this case) indicate co-appearance within a scene.

Note: The dataset originates from Gabasova, E. (2016). Star Wars social network. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1411479.

First, let’s visualize the data using nx.draw(G_starWars, with_labels = True):

Characters who frequently appear together, such as R2-D2 and C-3PO, are depicted in close proximity. Conversely, we can observe that Darth Vader does not share any scenes with Owen.

Unraveling NetworkX Visualization Layouts in Python

What determines the specific location of each node in the previous graph?

The answer lies in the default spring_layout algorithm. This algorithm simulates the force exerted by a spring, attracting connected nodes and repelling disconnected ones. Consequently, well-connected nodes, which gravitate towards the center, are prominently highlighted.

NetworkX offers alternative layouts that employ different criteria for node positioning, such as circular_layout:

| |

This results in the following arrangement:

This layout is considered neutral because the position of a node is independent of its importance—all nodes are represented with equal prominence. (The circular layout can also be helpful in visualizing distinct connected components—subgraphs with a path connecting any two nodes—but in this instance, the entire graph constitutes a single connected component.)

Both layouts we’ve examined exhibit a degree of visual clutter due to edges intersecting. However, Kamada-Kawai, another force-directed algorithm akin to spring_layout, strategically positions nodes to minimize system energy.

While this approach reduces edge-crossing, it comes at a cost: it’s slower than other layouts and therefore not ideal for graphs containing a large number of nodes.

This layout utilizes a dedicated draw function:

| |

This results in the following configuration:

Without any explicit intervention, the algorithm placed central characters (such as Luke, Leia, and C-3PO) at the center, while less prominent characters (like Camie and General Dodonna) are positioned towards the periphery.

Visualizing the graph with a specific layout can yield intriguing qualitative insights. However, quantitative results are indispensable in any data science analysis, necessitating the definition of specific metrics.

Node Analysis: Delving into Degree and PageRank

Now that we have a clear visualization of our network, it’s valuable to characterize the nodes. Multiple metrics describe the characteristics of nodes, and in our example, of the characters.

A fundamental node metric is its degree: the number of edges connected to it. The degree of a Star Wars character’s node quantifies how many other characters they shared a scene with.

The degree() function can calculate the degree of a specific character or the entire network:

| |

Both commands yield the following output:

| |

Sorting nodes in descending order of degree can be accomplished with a single line of code:

| |

The output is as follows:

| |

However, degree, being a simple sum, doesn’t account for the specifics of individual edges. Does a given edge connect to an otherwise isolated node or to a node that’s connected to the entire network? Google’s PageRank algorithm addresses this by aggregating this information to assess the “importance” of a node within a network.

The PageRank metric can be conceptualized as an agent randomly traversing from one node to another. Nodes with better connectivity have more paths passing through them, making them more likely to be visited by the agent.

Such nodes will have a higher PageRank, which we can calculate using the NetworkX library:

| |

This code snippet prints Luke’s rank and a list of characters sorted by rank:

| |

Interestingly, Owen has the highest PageRank, surpassing Luke, who had the highest degree. This suggests that although Owen doesn’t share the most scenes overall, he shares scenes with several important characters, including Luke himself, R2-D2, and C-3PO.

In stark contrast, C-3PO, the character with the third-highest degree, has the lowest PageRank. While C-3PO has numerous connections, many are with less significant characters.

The key takeaway: Utilizing multiple metrics provides a more comprehensive understanding of the diverse characteristics of a graph’s nodes.

Unveiling Hidden Structures: Community Detection Algorithms

In Python graph analysis, identifying communities is often crucial. These are groups of nodes with strong internal connections but minimal connections to nodes outside their community.

Numerous algorithms exist for this purpose. Most fall under the umbrella of unsupervised machine learning algorithms because they assign labels to nodes without requiring prior labeling.

One of the most renowned algorithms is label propagation. In this approach, each node starts with a unique label, effectively forming a community of one. Node labels are iteratively updated based on the majority label among their neighboring nodes.

Labels propagate through the network until all nodes share a label with most of their neighbors. Consequently, groups of closely connected nodes end up with the same label.

Implementing this algorithm with the NetworkX library is remarkably concise, requiring just three lines of Python code:

| |

This yields the following output:

| |

In this list of sets, each set represents a community. Those familiar with the movie will notice that the algorithm flawlessly separates the “good guys” from the “bad guys,” effectively differentiating the characters without relying on any true (community) labels or metadata.

Unlocking Intelligent Insights with Graph Data Science in Python

As we’ve seen, getting started with graph data science tools is more approachable than it may initially appear. Once data is represented as a graph using the NetworkX library in Python, a few lines of code can be incredibly revealing. We can visualize our dataset, quantify and compare node characteristics, and intelligently cluster nodes using community detection algorithms.

The ability to extract conclusions and insights from a network using Python empowers developers to integrate with tools and methodologies commonly employed in data science service pipelines. From search engines to flight scheduling to electrical engineering, these methods have broad applicability across a wide range of domains.

Recommended Reading on Graph Data Science

Community Detection Algorithms Zhao Yang, René Algesheimer, and Claudio Tessone. “A Comparative Analysis of Community Detection Algorithms on Artificial Networks.” Scientific Reports, 6, no. 30750 (2016). Graph Deep Learning Thomas Kipf. “Graph Convolutional Networks.” September 30, 2016. Applications of Graph Data Science Albanese, Federico, Leandro Lombardi, Esteban Feuerstein, and Pablo Balenzuela. “Predicting Shifting Individuals Using Text Mining and Graph Machine Learning on Twitter.” (August 24, 2020): arXiv:2008.10749 [cs.SI]. Cohen, Elior. “PyData Tel Aviv Meetup: Node2vec.” YouTube. November 22, 2018. Video, 21:09. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=828rZgV9t1g.