The extraction of data from websites, known as web scraping, has been practiced since the early days of the World Wide Web. Initially focused on static pages with predictable elements and tags, the evolution of web development technologies has introduced complexities to this process. This article delves into approaches for scraping data from websites that employ modern technologies, posing challenges to conventional scraping methods.

Traditional Data Scraping

Given that websites are primarily designed for human consumption, traditional web scraping involved programmatically parsing a webpage’s markup (viewable via “View Source”), identifying static patterns within the data to extract specific information, and storing it in a file or database.

Retrieving report data often involved submitting form variables or parameters through the URL, as illustrated below:

| |

Python, equipped with numerous web libraries, has gained significant traction as a preferred language for web scraping. The widely used Python library, Beautiful Soup, facilitates the extraction of data from HTML and XML files by enabling functionalities like searching, navigating, and manipulating the parse tree.

Browser-based Scraping

A recent scraping endeavor, initially perceived as straightforward and amenable to traditional techniques, presented unforeseen obstacles that necessitated a different approach.

The following three key challenges rendered traditional scraping methods ineffective:

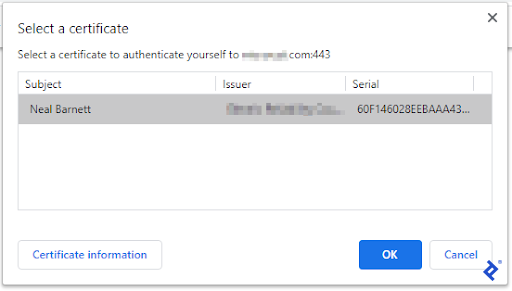

- Certificate Requirement: Accessing the relevant website section mandated the installation of a certificate. Upon accessing the initial page, a prompt required manual selection of the appropriate certificate.

- Iframe Utilization: The website’s use of iframes disrupted the conventional scraping workflow. While mapping all iframe URLs to construct a sitemap was an option, it appeared cumbersome.

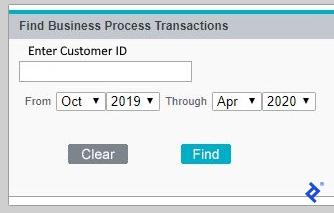

- JavaScript Integration: Data access involved a form with parameters (e.g., customer ID, date range), typically bypassed in traditional scraping by directly submitting form variables. However, the form’s JavaScript implementation prevented standard access to these variables.

These limitations prompted the exploration of browser-based scraping tools. Unlike the direct page access, parse tree download, and data element extraction of traditional methods, this approach emulates human interaction with a browser to navigate to the desired page and then performs scraping, effectively circumventing the aforementioned barriers.

Web Scraping With Selenium

Primarily recognized as an open-source testing framework for web applications, Selenium](https://www.selenium.dev) empowers QA professionals to automate tests, execute playbacks, and utilize remote control functionality, enabling load testing with multiple browser instances and compatibility across various browser types. Its potential applicability to the scraping challenge was evident.

Given Python’s robust library support, making it a preferred choice for web scraping, the availability of a dedicated Selenium library for Python further solidified its suitability. This library facilitated the instantiation of a “browser” (Chrome, Firefox, IE, etc.) and allowed programmatic interaction with it, simulating human navigation to access the desired data. The “headless” mode offered the flexibility of running the browser invisibly, if required.

Project Setup

A Windows 10 machine with a reasonably updated Python version (v. 3.7.3) served as the development environment. A new Python script was created, and necessary libraries were installed or updated using PIP, the Python package installer. The essential libraries included:

- Requests (for handling HTTP requests)

- URLLib3 (for URL manipulation)

- Beautiful Soup (as a fallback if Selenium encountered limitations)

- Selenium (for browser-based navigation)

To facilitate experimentation with various datasets, command-line arguments (using the argparse library) were added, allowing the script to be invoked with parameters like Customer ID, from-month/year, and to-month/year.

Problem 1 – The Certificate

Chrome was chosen as the Selenium browser due to its familiarity and foundation on the open-source Chromium project (also used by Edge, Opera, and Amazon Silk).

Initializing Chrome within the script involved importing the required library components and executing a few straightforward commands:

| |

Without launching in headless mode, the browser window appeared, providing visual feedback. Immediately, the certificate selection prompt was displayed.

The initial hurdle was automating the certificate selection process, eliminating manual intervention. The first script execution resulted in the following prompt:

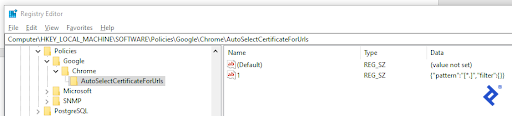

This manual intervention was undesirable. While a programmatic solution was preferable, a workaround was discovered within Chrome’s settings. Chrome lacked the ability to pass a certificate name during startup. However, it could autoselect a certificate based on a specific Windows registry entry, either selecting the first available certificate or a specific one. Given that only one certificate was installed, the generic format was used.

With this configuration, Selenium’s Chrome instantiation would trigger Chrome’s “AutoSelect” functionality, automatically selecting the certificate and proceeding.

Problem 2 – Iframes

Upon successful website access, a form requesting customer ID and date range input was presented.

Inspecting the form using developer tools (F12) revealed its presence within an iframe. Switching to the iframe containing the form was necessary before proceeding. Selenium’s switch-to functionality accomplished this:

| |

Within the correct iframe context, the form components were identifiable, allowing population of the customer ID field and selection of dates from the dropdowns:

| |

Problem 3 – JavaScript

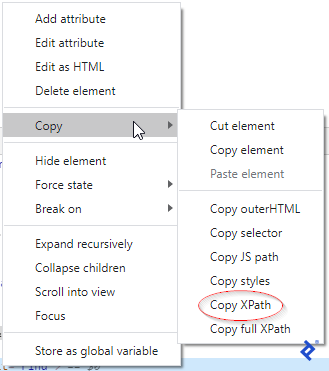

The final step involved “clicking” the form’s Find button. This presented a challenge as the button appeared to be controlled by JavaScript, lacking the characteristics of a typical “Submit” button. Inspecting the button image in developer tools and right-clicking revealed its XPath.

Equipped with the XPath, the element was located and clicked.

| |

This action successfully submitted the form, and the desired data was displayed. The remaining task was to scrape the data from the results page.

Getting the Data

Handling empty search results was straightforward. The search form would persist, displaying a message like “No records found.” Searching for this string and terminating the script if found addressed this scenario.

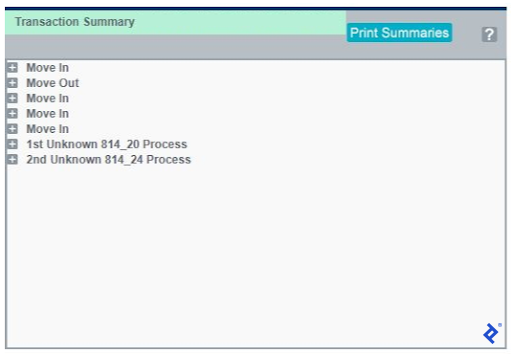

Successful results were presented in divs, each expandable via a plus sign (+) to reveal transaction details. An opened transaction displayed a minus sign (-) for collapsing the div. Clicking a plus sign would fetch data via a URL to populate its div and close any open ones.

Therefore, identifying all plus signs on the page, extracting their associated URLs, and iterating through them was necessary to gather data for each transaction.

| |

The code snippet above demonstrates the retrieval of transaction type and status fields, incrementing a counter for transactions matching the specified criteria. Other data fields within the transaction details, such as date, time, and subtype, could also be extracted.

In this project, the final count was returned to the calling application. However, this data, along with other scraped information, could be stored in a flat file or a database.

Additional Possible Roadblocks and Solutions

Modern websites often present additional challenges during browser-based scraping, most of which are resolvable. Here are a few examples:

Delayed Element Appearance:

Similar to human browsing, encountering delays while waiting for page elements to load is common. Programmatically, this translates to searching for elements that haven’t rendered yet.

Selenium addresses this with its ability to wait for a specific element’s appearance, incorporating timeouts if the element remains undetected:

| |

Captcha Challenges:

Websites frequently employ Captcha or similar mechanisms to deter automated bots (which your scraper might be mistaken for). Overcoming these hurdles can significantly impact scraping speed.

Simple prompts (like “what’s 2 + 3?”) are easily solvable. However, dedicated libraries like 2Captcha, Death by Captcha, and Bypass Captcha assist in tackling more sophisticated barriers.

Website Structural Changes:

Websites are dynamic and subject to change, a factor to consider during script development. Opting for robust element identification methods and avoiding overly specific matches is crucial. For instance, a website might modify a message from “No records found” to “No records located,” but a match based on “No records” would still function correctly. Carefully selecting identification criteria (XPATH, ID, name, link text, tag or class name, CSS selector) based on their resistance to change is essential.

Summary: Python and Selenium

This demonstration highlights that most websites, regardless of their technological complexity, are susceptible to scraping. The general rule is: if you can browse it, you can likely scrape it.

However, it’s crucial to acknowledge that not all websites should be subjected to scraping. Some have legitimate restrictions in place, and numerous court cases have addressed the legality of scraping certain websites. Conversely, some encourage data retrieval and even provide APIs to facilitate the process.

Before initiating any scraping project, it’s best practice to review the website’s terms and conditions. Should you proceed, rest assured that tools and techniques are available to accomplish the task.

Recommended Resource for Complex Python Web Scraping:

- Scalable do-it-yourself scraping: How to build and run scrapers on a large scale