React design patterns offer software developers two primary benefits. Firstly, they provide a straightforward method to tackle software development challenges using proven solutions. Secondly, they significantly streamline the process of building highly cohesive modules with reduced interdependence. This article delves into the most essential React-specific design patterns and best practices, while also exploring the utility of general design patterns across various React use cases.

Commonly Used React Design Patterns

While general design patterns are applicable in React, React developers benefit most from patterns specifically tailored for the framework. Let’s explore the fundamental ones: higher-order components, providers, compound components, and hooks.

Higher-order Components (HOC)

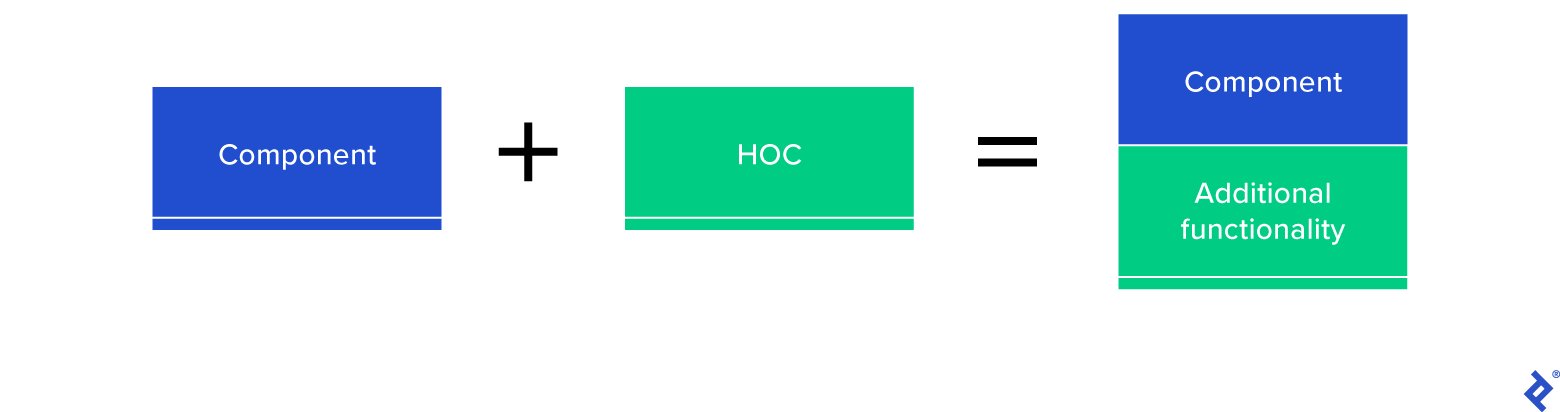

Higher-order components (HOC) utilize props to furnish reusable logic to components. When there’s a need to augment existing component functionality with a fresh UI, HOCs come into play.

Combining a component with a HOC yields the desired outcome: a component enhanced with capabilities beyond the original.

In code, this involves wrapping a component within a HOC, which returns the desired augmented component:

| |

The logic within HOCs can vary; architecturally, they are prevalent in Redux.

Provider Design Pattern

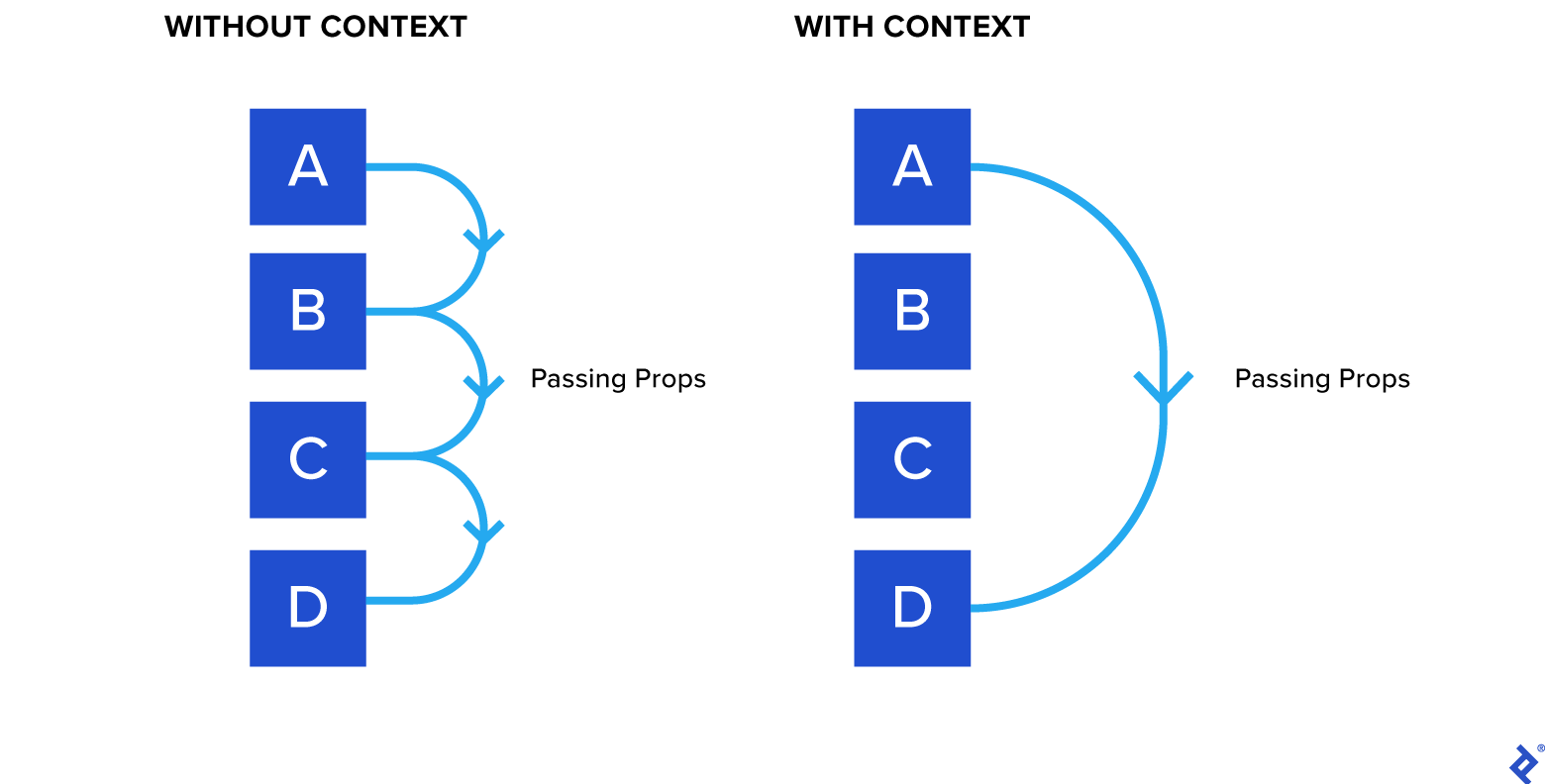

The provider design pattern helps circumvent prop drilling, the process of passing props down to deeply nested components within a component tree. This pattern is achievable using React’s Context API:

| |

This code snippet illustrating the provider pattern demonstrates direct prop passing to a newly created object via context. Context encompasses both a state provider and consumer; in this case, the provider is an app component, while a book component consuming BookContext acts as the consumer. Here’s a visual representation:

Direct prop transmission from component A to component D signifies the use of the provider design pattern. Without it, prop drilling would ensue, with B and C acting as intermediaries.

Compound Components

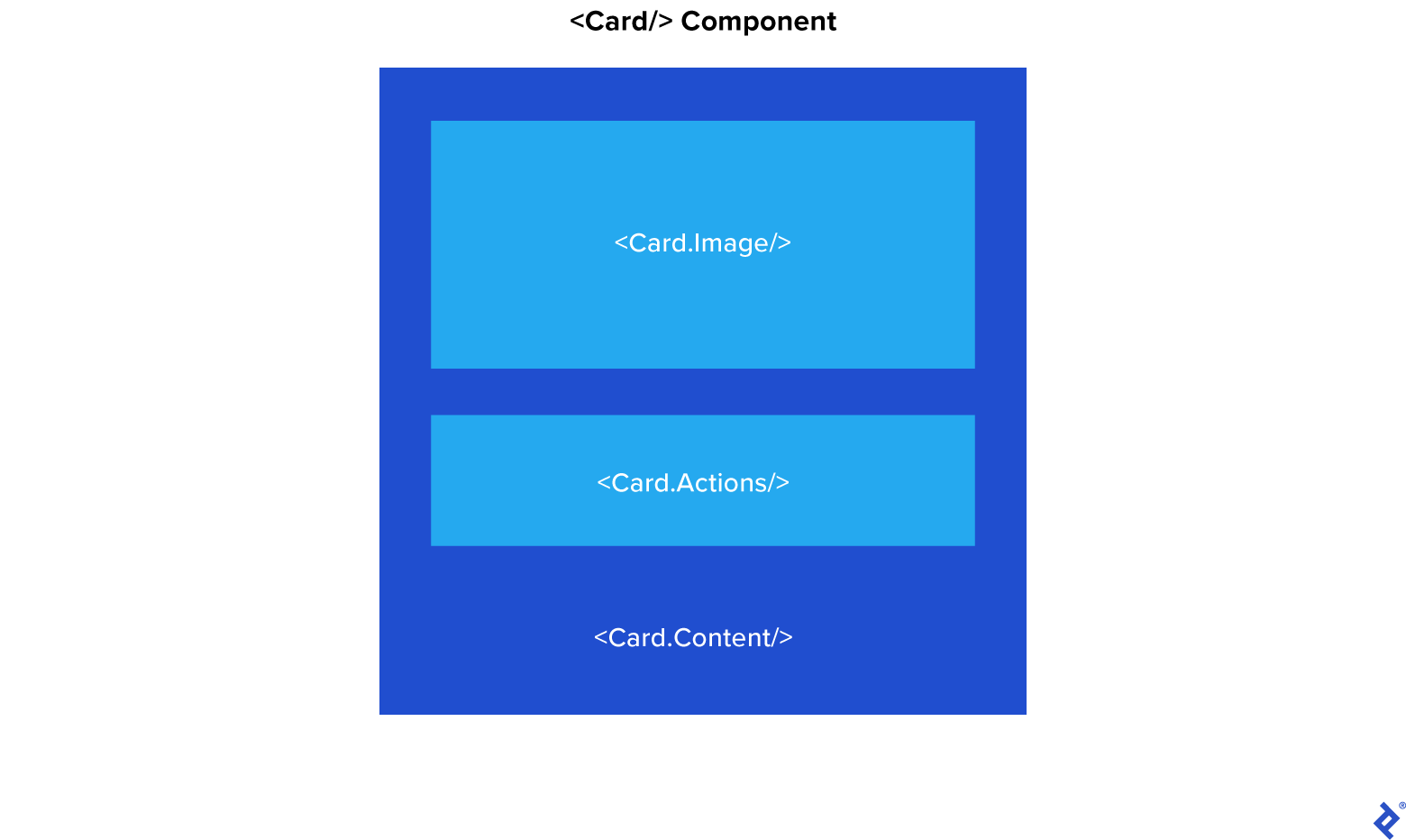

Compound components are essentially sets of interconnected parts that collaborate to deliver a unified functionality. A simple illustration is a card component with its constituent elements.

This card component comprises an image, actions, and content, all working in conjunction to provide its functionality:

| |

The compound component API offers a user-friendly way to articulate relationships between components.

Hooks

React hooks provide a mechanism to manage a component’s state and lifecycle procedures. Introduced in early 2019, with a wider array becoming available in React version 16.8, hooks encompass state, effect, and custom hooks.

React’s state hook (useState) is structured with two elements: the current value and a function to update it based on state changes:

| |

Let’s delve into a more concrete example of the state hook:

| |

Here, we initialize a state with an empty string as its current value ("") and can modify its value using the onChange handler.

Class-based components also feature effect hooks (useEffect). The useEffect hook’s functionalities mirror those of React’s earlier lifecycle methods: componentDidMount, componentWillMount, and componentDidUpdate.

While skilled React developers are likely well-versed in hooks, HOCs, providers, and compound components, the best engineers also possess a strong grasp of general design patterns, such as proxies and singletons, and recognize their appropriate application within React.

Exploring General Design Patterns in React

General design patterns transcend language and framework constraints, offering solutions adaptable to various situations. This universality simplifies system comprehension and maintenance, while also facilitating communication among developers. By referencing pattern names, software professionals can readily convey and understand high-level design choices.

Design patterns are broadly categorized into three types:

- Creational

- Structural

- Behavioral

These patterns prove valuable in React, and their applicability extends to JavaScript programming in general, making this knowledge highly transferable.

Creational Design Patterns in React

Creational design patterns center around object creation tailored to diverse scenarios, enhancing flexibility and reusability.

Builder Design Pattern

The builder design pattern streamlines object creation by outlining a step-by-step process and delivering the result of these combined steps:

| |

This pattern decouples the creation of a complex object from its representation, enabling the generation of different representations using the same construction process.

Singleton Design Pattern

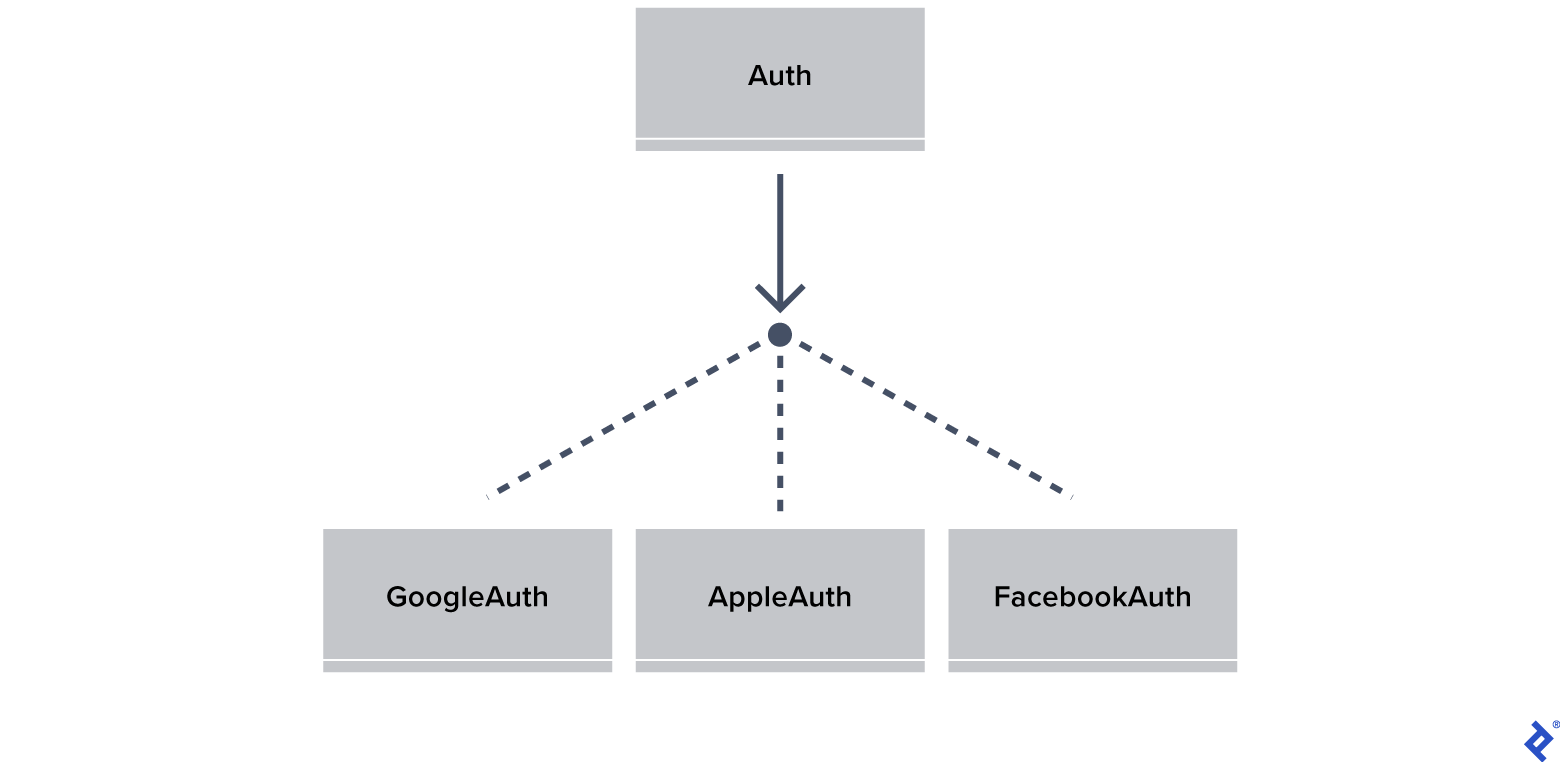

The singleton design pattern restricts class instantiation to a single object. A common use case is ensuring only one authentication instance exists when a user selects from multiple login options:

Consider an AuthComponent with a singleton method authInstance that manages types and renders state changes based on the chosen type. An authInstance shared across three components could dictate whether to render Google, Apple, or Facebook authentication components:

| |

A class adhering to the singleton pattern should have a single instance and a global access point. Singletons are best suited for situations where:

- Assigning logical ownership of a single instance is impractical.

- Lazy initialization of an object is desired.

- Global access to an instance is unnecessary.

Lazy initialization, a performance optimization technique, delays object creation until absolutely necessary.

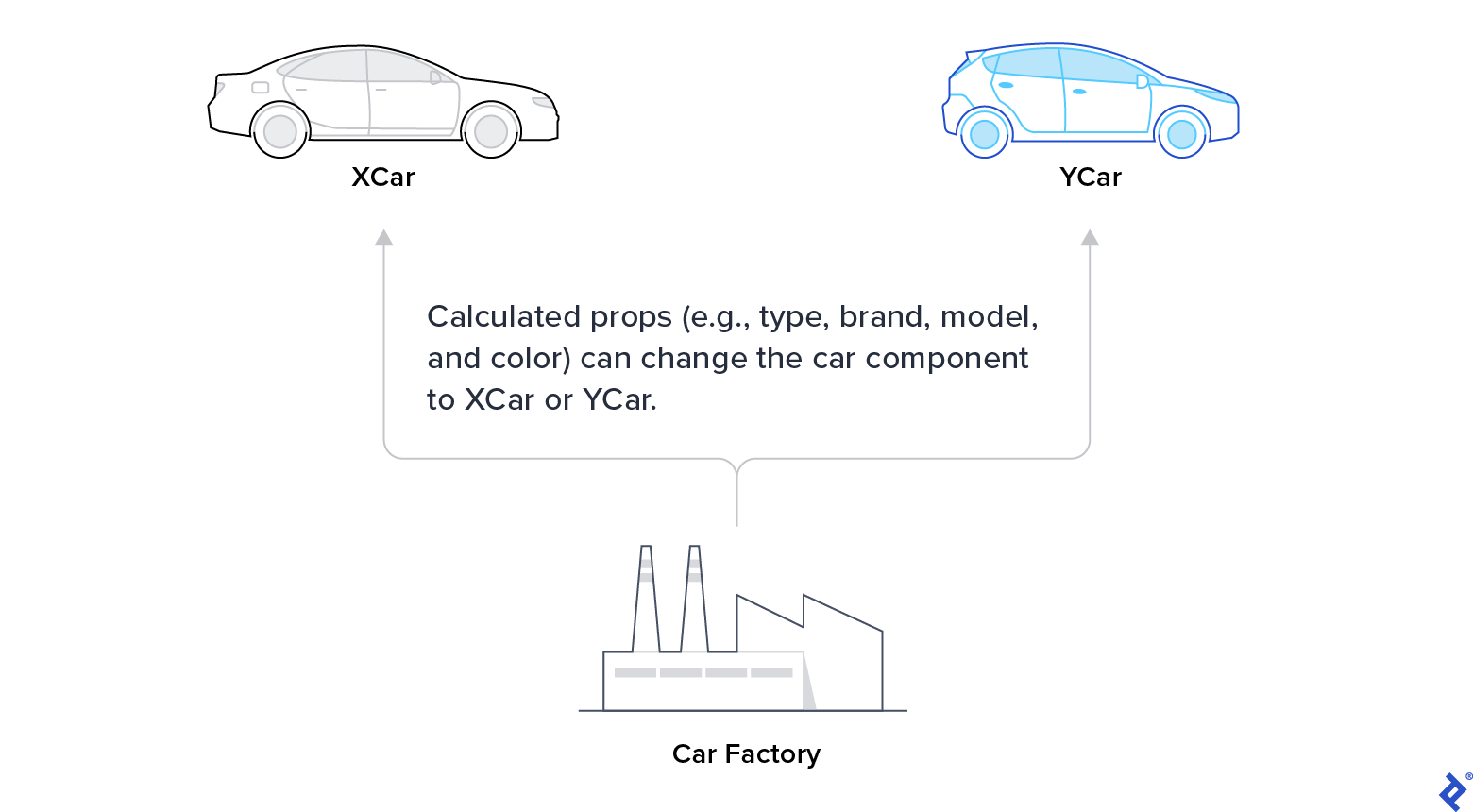

Factory Design Pattern

The factory design pattern proves useful when dealing with a superclass and multiple subclasses, where the goal is to return a specific subclass based on provided input. This pattern delegates class instantiation responsibility from the client program to a dedicated factory class.

Object creation is streamlined using this pattern. Imagine a car component customizable into various subcar components by modifying its behavior. The factory pattern leverages both polymorphism and interfaces, as objects (different cars) are created at runtime.

In the code snippet below, we observe abstract cars with carModel, brandName, and color props. The CarFactory, while named as such, houses categories based on brand names. The XCar brand (e.g., Toyota) would create cars with specific attributes, yet still fall under the CarFactory abstraction. This allows for further customization of color, trim level, and engine displacement within the same Car factory component.

This implementation already utilizes inheritance as a blueprint for class components. By providing props to Car objects, we create distinct objects. Polymorphism is also evident, as the code determines the brand and model of each Car at runtime based on the provided types in different scenarios:

| |

Factory methods are typically defined by an architectural framework and implemented by its users.

Structural Design Patterns in React

Structural design patterns assist React developers in defining relationships between components, enabling grouping and simplification of complex structures.

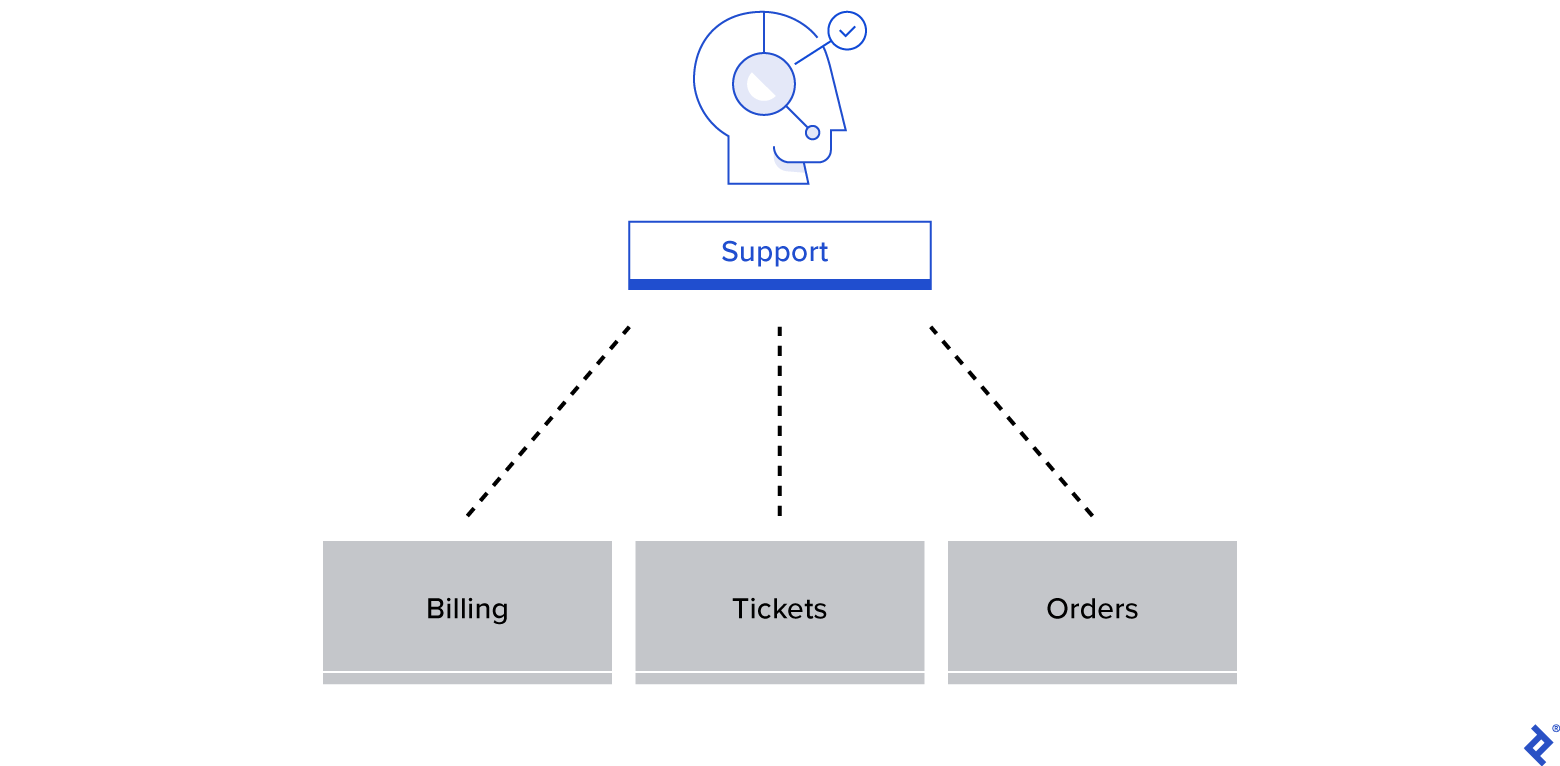

Facade Design Pattern

The facade design pattern aims to simplify interactions with multiple components by introducing a single, unified API. This abstraction enhances code readability and can help group generic functionalities into specific contexts, proving particularly beneficial in complex systems with intricate interaction patterns.

An example is a support department handling various responsibilities, such as verifying billing, support tickets, or order placement.

Let’s consider an API with get, post, and delete methods:

| |

Completing this facade pattern example:

| |

A key limitation of the facade pattern is its suitability for scenarios where a subset of clients require a streamlined interface to access the full functionality of a complex subsystem.

Decorator Design Pattern

The decorator design pattern employs layered, wrapper objects to augment the behavior of existing objects without altering their internal workings. This enables infinite layering of components, with outer components dynamically changing their behavior while leaving the base component unaffected. The base component remains a pure function returning a new component without side effects.

HOCs exemplify this pattern. (While memo presents a prime use case for decorator patterns, it’s not covered here due to the numerous good examples available online.)

Exploring decorator patterns in React:

| |

Here, canFly is a method usable anywhere without side effects. Decorators can be applied to class components or functions within class or functional components.

While decorators are powerful for writing cleaner and more maintainable React components, HOCs are often preferred over class decorators. Decorators, being an ECMAScript proposal, are subject to change, warranting caution in their use.

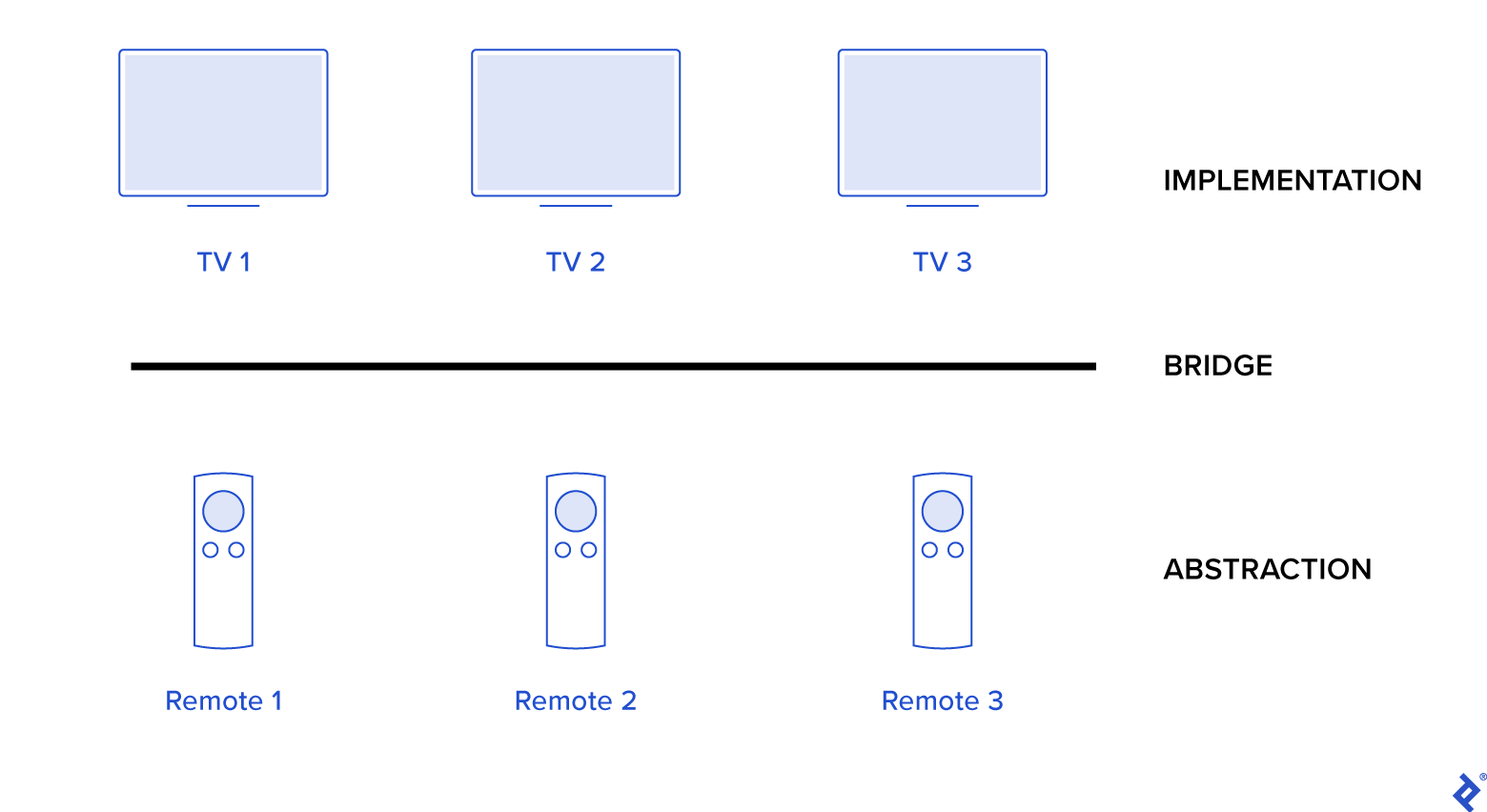

Bridge Design Pattern

The bridge design pattern holds significant value in front-end development by separating an abstraction from its implementation, allowing independent modification of both.

This pattern is employed when: runtime implementation binding is desired; excessive classes arise from a coupled interface and numerous implementations; implementation sharing among multiple objects is needed; or mapping of orthogonal class hierarchies is required.

Illustrating the bridge pattern with a TV and controller example:

Imagine each TV and remote belonging to different brands. Each remote would be associated with its brand. A Samsung TV would require a Samsung remote; a Sony remote, despite having similar buttons (on, off, channel up, down), wouldn’t work due to differing implementations.

| |

The bridge design pattern necessitates maintaining correct references reflecting accurate changes.

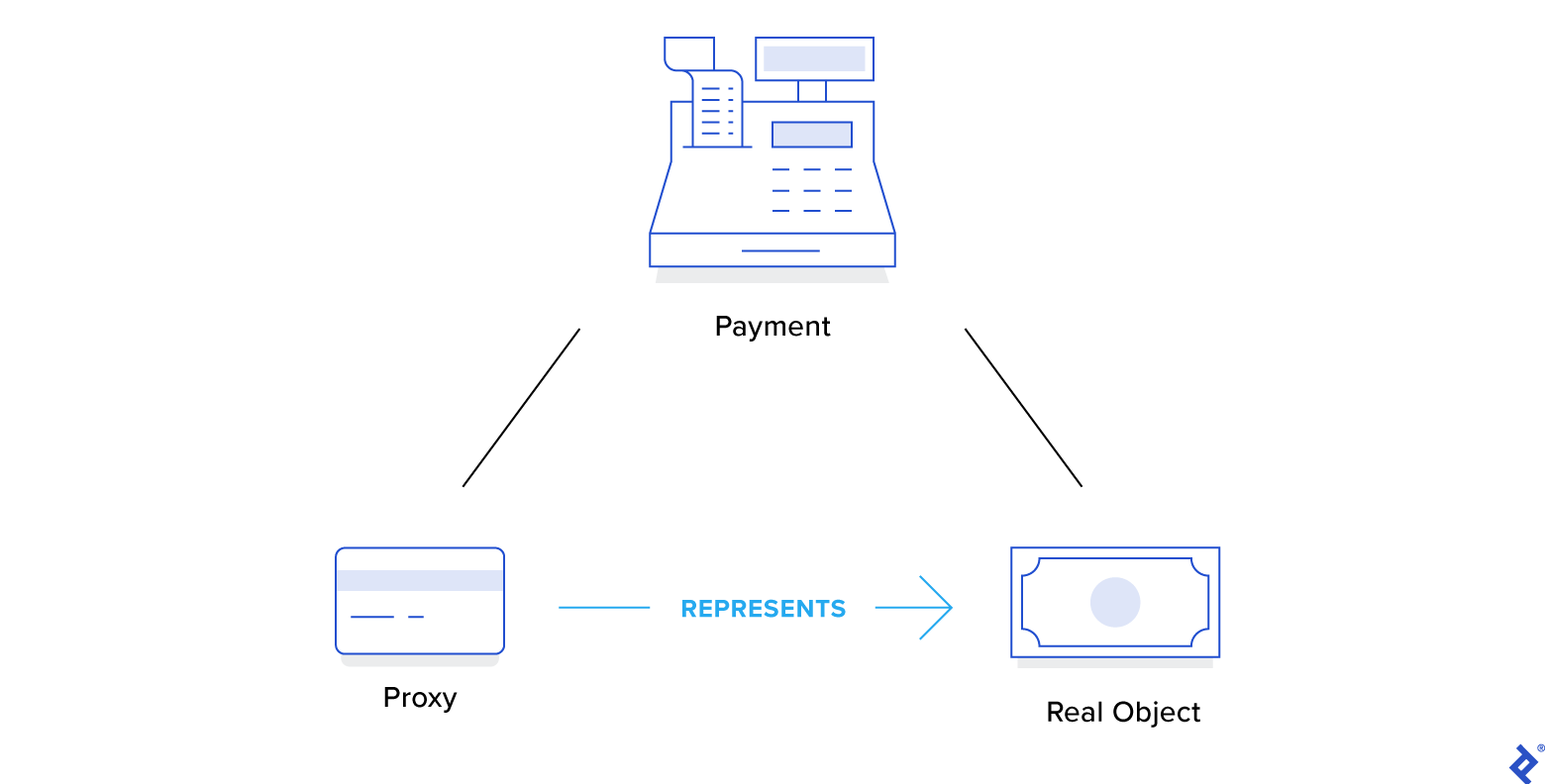

Proxy Design Pattern

The proxy design pattern introduces a proxy object acting as a surrogate or placeholder for accessing another object. A relatable example is a credit card representing physical cash or bank account funds.

Demonstrating this pattern in code with a funds transfer example where a payment application verifies the available bank account balance:

| |

Here, the payment app’s balance verification acts as the proxy.

Behavioral Design Patterns in React

Behavioral design patterns focus on inter-component communication, making them particularly relevant to React’s component-centric nature.

State Design Pattern

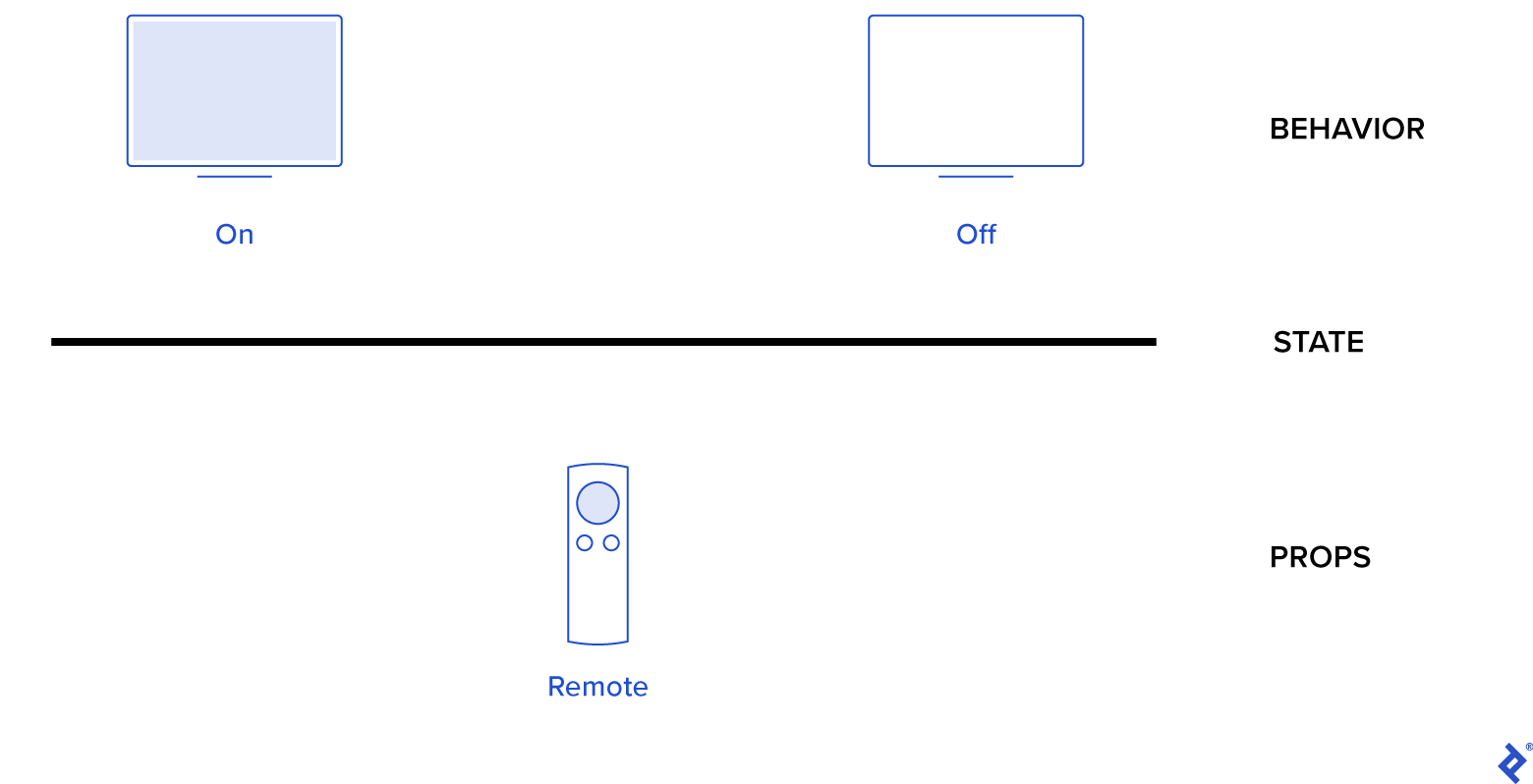

The state design pattern is widely used to incorporate basic encapsulation units (states) in component programming. A TV’s behavior changing based on remote control input exemplifies this pattern:

The TV’s state (on or off) changes based on the state of the remote button. Similarly, in React, component state is altered based on props or other conditions.

An object’s behavior is modified when its state changes:

| |

The WithState component behaves differently in these examples depending on whether a state prop is provided or set to null. This state-dependent behavior change is why it’s classified as a behavioral pattern.

Command Design Pattern

The command design pattern excels in designing clean, decoupled systems, enabling execution of business logic at a future point. This pattern is particularly interesting as it underpins Redux. Let’s see its application with a Redux reducer:

| |

The Redux reducer in this example contains multiple cases triggered by different events, each returning distinct behaviors.

Observer Design Pattern

The observer design pattern allows objects to subscribe to state changes in another object, receiving automatic notifications upon such changes. This decouples observing objects from the observed, promoting modularity and flexibility.

In Model-View-Controller (MVC) architecture, this pattern is commonly used to propagate model changes to views, enabling view updates without direct access to the model’s internal data:

| |

While the observer pattern uses “observer” and “subject” objects to manage communication, other patterns like the mediator encapsulate communication within an object. Creating reusable observables is generally easier than reusable mediators, but mediators can leverage observers for dynamic colleague registration and communication.

Strategy Design Pattern

The strategy design pattern enables dynamic behavior modification from the outside without altering the base component. It defines a family of algorithms, encapsulates each, and makes them interchangeable, allowing independent changes in the parent component and its children. Abstraction resides in an interface, while implementation details are hidden within derived classes:

| |

As the open-closed principle dominates object-oriented design, this pattern helps adhere to OOP principles while maintaining runtime flexibility.

Memento Design Pattern

The memento design pattern captures and externalizes an object’s internal state for later restoration without violating encapsulation. It involves:

- Originator: The object capable of saving its state.

- Caretaker: Manages the conditions under which the originator saves and restores its state.

- Memento: Stores the originator’s state, managed by the caretaker and accessed by the originator.

Illustrating with a code example. The memento pattern utilizes the chrome.storage API (implementation details omitted) for data storage and retrieval. This conceptual example showcases data setting in setState and loading in getState:

| |

However, the practical React implementation looks like this:

| |

Here, getState is returned within the organizer (handler), while a subset of the state is returned in the two logical branches of careTaker.

Significance of React Patterns

While patterns offer proven solutions to recurring problems, software engineers must carefully consider their benefits and drawbacks before implementation.

React developers frequently employ state, hooks, custom hooks, and the Context API. However, understanding and utilizing the general design patterns discussed here elevates their foundational skills, benefiting them across multiple languages. These patterns empower developers to articulate code behavior architecturally, going beyond simply addressing specific issues.

The editorial team at Toptal Engineering Blog expresses gratitude to Teimur Gasanov for reviewing the code samples and technical content in this article.