Let’s clarify a common misconception among Ruby developers: Concurrency and parallelism are not synonymous (concurrent != parallel).

Concurrency in Ruby means two tasks can start, run, and finish in overlapping timeframes. It doesn’t guarantee they’ll run simultaneously (e.g., multiple threads on a single-core CPU). Conversely, parallelism means two tasks execute simultaneously (e.g., multiple threads on a multicore CPU).

The key takeaway: Concurrent threads/processes aren’t always parallel.

This tutorial practically explores techniques for concurrency and parallelism in Ruby.

For real-world examples, see our article on Ruby Interpreters and Runtimes.

Our Test Case

We’ll use a Mailer class with a CPU-intensive Fibonacci function (instead of sleep()) for a simple test case:

| |

We can use this Mailer class to send mail:

| |

(Note: Source code is available here on GitHub.)

For comparison, let’s benchmark by invoking the mailer 100 times:

| |

This yielded these results on a quad-core processor with MRI Ruby 2.0.0p353:

| |

Multiple Processes vs. Multithreading

There’s no universal answer to choosing between multiple processes or multithreading in Ruby. This table outlines key factors:

| Processes | Threads |

|---|---|

| Uses more memory | Uses less memory |

| If parent dies before children have exited, children can become zombie processes | All threads die when the process dies (no chance of zombies) |

| More expensive for forked processes to switch context since OS needs to save and reload everything | Threads have considerably less overhead since they share address space and memory |

| Forked processes are given a new virtual memory space (process isolation) | Threads share the same memory, so need to control and deal with concurrent memory issues |

| Requires inter-process communication | Can "communicate" via queues and shared memory |

| Slower to create and destroy | Faster to create and destroy |

| Easier to code and debug | Can be significantly more complex to code and debug |

Ruby solutions using multiple processes:

- Resque: A Redis-backed library for background jobs, queuing, and processing.

- Unicorn: An HTTP server for Rack apps optimized for fast clients and low-latency connections on Unix-like systems.

Ruby solutions using multithreading:

- Sidekiq: A comprehensive background processing framework for Ruby, offering easy Rails integration and high performance.

- Puma: A Ruby web server built for concurrency.

- Thin: A fast and simple Ruby web server.

Multiple Processes

Before multithreading, let’s explore spawning multiple processes.

Ruby’s fork() system call creates a process “copy,” scheduled independently by the OS, enabling concurrency. (Note: fork() is POSIX-specific, unavailable on Windows.)

Let’s run our test case with fork():

| |

(Process.waitall waits for all child processes, returning their statuses.)

Results on a quad-core processor with MRI Ruby 2.0.0p353:

| |

A ~5x speed increase with a few code changes!

However, forking’s memory consumption is a major drawback, especially without a Copy-on-Write (CoW) in your Ruby interpreter. Forking a 20MB app 100 times could use 2GB of memory!

Multithreading has its complexities, but fork() brings challenges like shared file descriptors, semaphores, and inter-process communication via pipes.

Ruby Multithreading

Let’s try making the program faster using Ruby multithreading.

Multiple threads within a process have less overhead than processes due to shared memory.

Let’s revisit our test case with Ruby’s Thread class:

| |

Results on a quad-core processor with MRI Ruby 2.0.0p353:

| |

Disappointing! Why is it similar to synchronous execution?

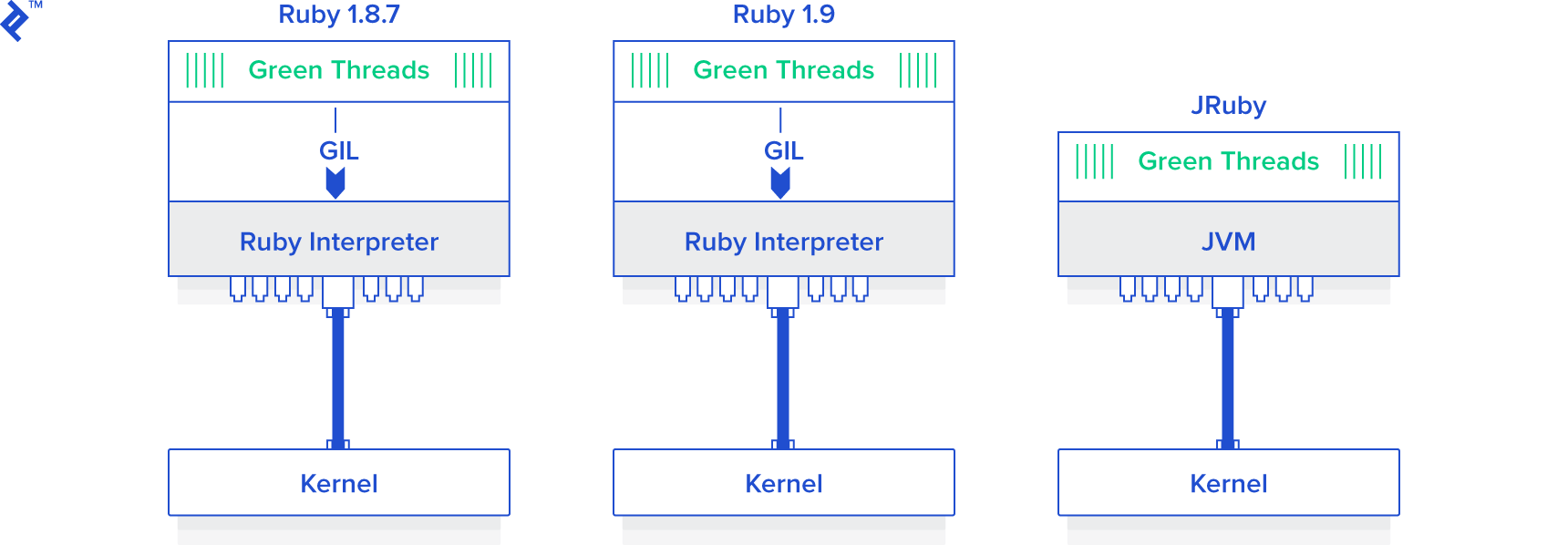

The culprit is the infamous Global Interpreter Lock (GIL). The GIL in CRuby (MRI) hinders true threading.

The Global Interpreter Lock synchronizes threads in interpreters, allowing only one to execute at a time. GIL-based interpreters (like Ruby MRI and CPython) execute one thread at a time, even on multi-core CPUs.

How can we leverage multithreading in Ruby with the GIL limitation?

Unfortunately, CRuby offers limited multithreading benefits.

However, Ruby concurrency (without parallelism) is useful for IO-bound tasks (e.g., network operations). Threads existed before multi-core systems for a reason.

Consider alternatives like JRuby or Rubinius if possible. They lack a GIL and support true parallel Ruby threading.

Here’s the threaded code on JRuby (instead of CRuby):

| |

That’s more like it!

However…

Threads Ain’t Free

Improved performance with threads doesn’t mean unlimited scalability. Threads consume resources, leading to limitations.

Let’s run the mailer 10,000 times instead of 100:

| |

An error occurred on OS X 10.8 after spawning around 2,000 threads:

| |

Resource exhaustion is inevitable, limiting scalability.

Thread Pooling

Fortunately, thread pooling offers a solution.

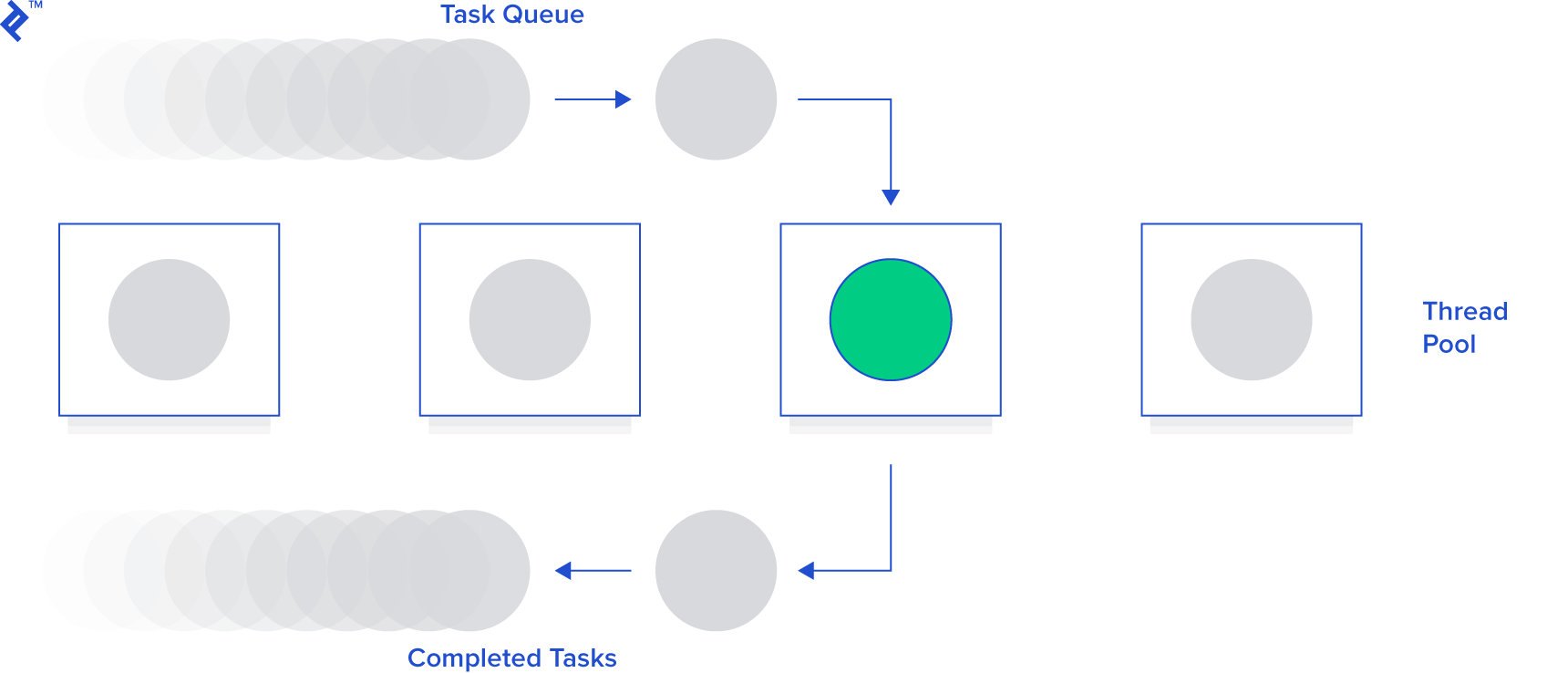

A thread pool is a collection of pre-created, reusable threads for task execution. It’s beneficial for numerous short tasks, minimizing thread creation overhead.

A crucial parameter is the pool size (number of threads). Threads can be instantiated upfront or lazily (as needed).

When assigned a task, the pool uses an idle thread. If none are available (and the maximum is reached), it waits for a thread to become free.

Let’s use Queue (a thread safe data type) for a simple thread pool implementation:

require “./lib/mailer” require “benchmark” require ‘thread’

| |

We used Queue for thread-safe job queuing, avoiding complex implementations with a mutex.

We pushed mailer IDs to the queue and created ten worker threads.

Each worker thread pops tasks from the queue, executing them upon availability.

This solution is scalable but relatively complex.

Celluloid

The Ruby Gem ecosystem offers gems that simplify multithreading.

Celluloid is an excellent example. It provides a clean way to implement actor-based concurrency in Ruby. Celluloid allows building concurrent programs with concurrent objects as easily as sequential ones.

We’ll focus on the Pools feature, but explore Celluloid further. It helps build multithreaded Ruby programs without deadlocks and offers features like Futures and Promises.

Here’s our mailer using Celluloid:

| |

Clean, simple, scalable, and robust.

Background Jobs

Another option, depending on your needs, is background jobs. Several Ruby Gems support background processing (queuing and processing jobs asynchronously). Popular choices include Sidekiq, Resque, Delayed Job, and Beanstalkd.

We’ll use Sidekiq with Redis (a key-value store).

First, install and run Redis locally:

| |

With Redis running, here’s our mailer (mail_worker.rb) using Sidekiq:

| |

Trigger Sidekiq with mail_worker.rb:

| |

And from IRB:

| |

Incredibly simple and easily scalable by adjusting the worker count.

Sucker Punch, another asynchronous RoR processing library, is another option. The implementation with Sucker Punch is similar, replacing Sidekiq::Worker with SuckerPunch::Job and MailWorker.perform_async() with MailWorker.new.async.perform().

Conclusion

Achieving high concurrency in Ruby is simpler than you might think.

Forking multiplies processing power, while multithreading offers a lighter-weight approach but requires managing resources. Thread pools address resource limitations. Gems like Celluloid simplify multithreading with its Actor model.

Background processing provides an alternative for time-consuming tasks, with various libraries and services available. Popular options include database-backed job frameworks and message queues.

Forking, threading, and background processing are all valid options. Choose the best fit for your application, environment, and requirements. Hopefully, this tutorial has provided a helpful overview.