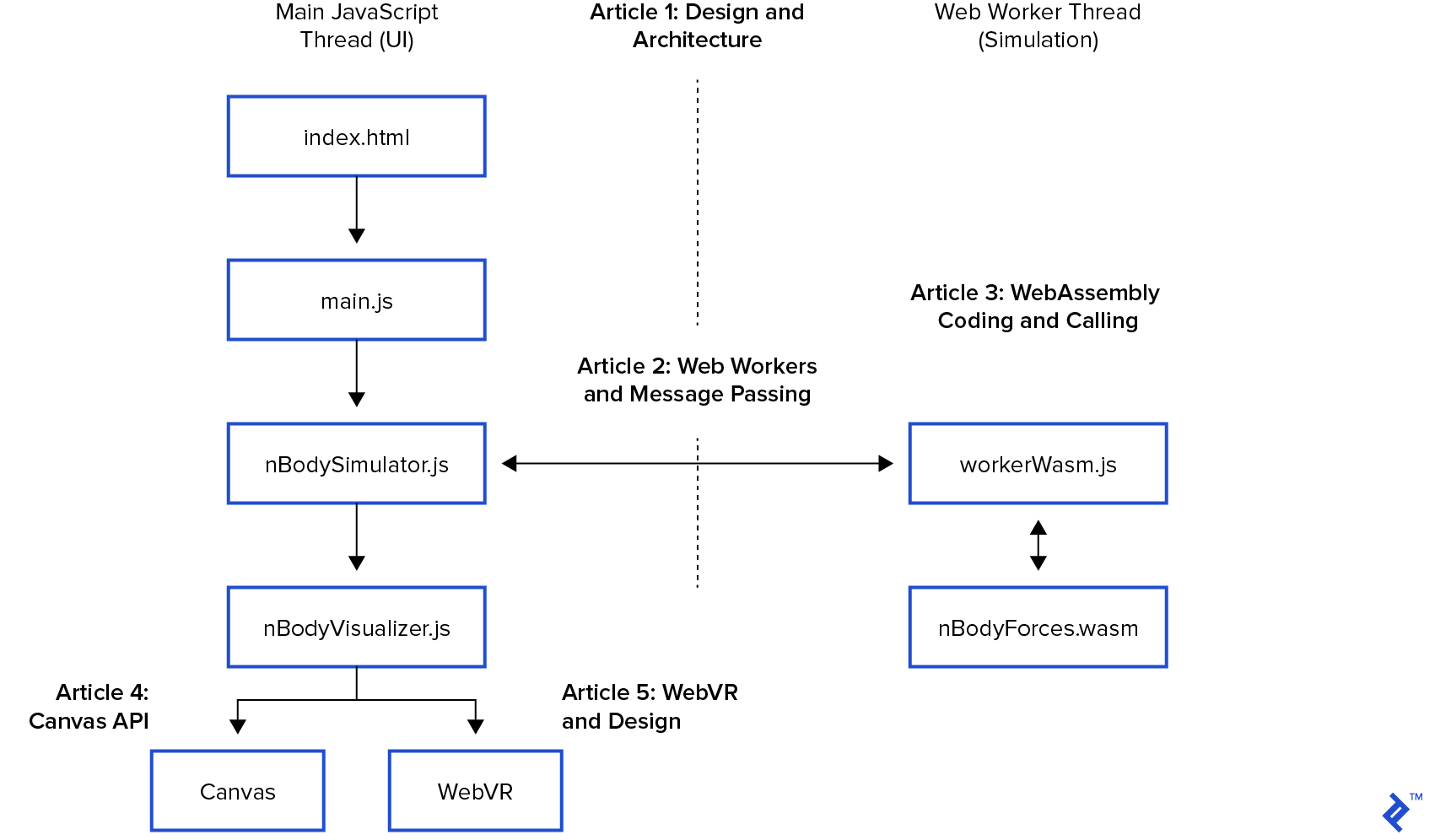

The thrill of completion is real, and with this final step, we’ve birthed a celestial gravity simulation in WebVR. This article will guide us through integrating our high-performance simulation code (explained in Articles 1-3) with a WebVR visualizer, building on the canvas visualizer from Article 4.

For those joining us mid-journey, the previous articles provide context:

- “n-body problem” Intro and Architecture

- Web Workers for Additional Browser Threads

- WebAssembly and AssemblyScript for O(n²) Performance

- Canvas Data Visualization

- WebVR Data Visualization

To keep things concise, we’ll gloss over some previously covered technical details. Feel free to revisit earlier posts for a refresher, or dive right in.

This series has explored the browser’s evolution from a single-threaded JavaScript runtime to a multi-threaded powerhouse using web workers and WebAssembly. These advancements, reminiscent of desktop computing, are now accessible in Progressive Web Apps and the SaaS model.

VR is poised to revolutionize sales and marketing, offering immersive, distraction-free environments for communication, persuasion, and engagement measurement through eye tracking and interaction. While data remains fundamental, executive summaries and consumer experiences will be delivered through WebVR, much like mobile dashboards for the flat web.

These technologies also empower distributed browser edge computing. Imagine a web application simulating millions of stars with WebAssembly computations, or an animation tool rendering others’ creations during your editing process.

Entertainment, as it often does, is spearheading VR adoption, similar to its role in mobile’s rise. However, as VR becomes ubiquitous (like mobile-first design), it will become the expected standard (VR-first design). This is an exhilarating era for designers and developers, with VR presenting a radically different design paradigm.

A bold statement: you’re not a true VR designer unless you can grip. This field is constantly evolving. My goal is to share insights from software and film to fuel the “VR-first design” dialogue. We all learn and grow together.

Driven by these grand possibilities, I envisioned this project as a polished tech demo, and WebVR fits the bill perfectly!

WebVR and Google A-Frame

The WebVR git repo is a modified version of the canvas version for practical reasons: easier hosting on Github pages and accommodating WebVR changes without cluttering the canvas codebase.

Recall from our initial architecture discussion that the entire simulation was delegated to nBodySimulator.

In the web worker article, nBodySimulator’s step() function, called every 33ms, invoked calculateForces() (our O(n²) WebAssembly code from Article 3) to update positions and refresh the display. In the canvas visualization post, we achieved this with a canvas element, extending the following base class:

| |

The Integration Challenge

With the simulation in place, our goal is seamless integration with WebVR without restructuring the project. All modifications within the simulation occur every 33ms in the main UI thread’s paint(bodies) function.

This marks our “finish line.” Let’s get this done!

Constructing Virtual Reality

First, a design blueprint:

- What constitutes VR?

- How is WebVR design articulated?

- How do we enable interaction within VR?

Virtual Reality’s roots run deep, echoing in every campfire story—tiny virtual worlds built on embellished tales and mundane details.

Imagine amplifying these stories tenfold with 3D visuals and audio. As my film production budgeting instructor would say, “We’re just paying for the poster; we’re not recreating reality.”

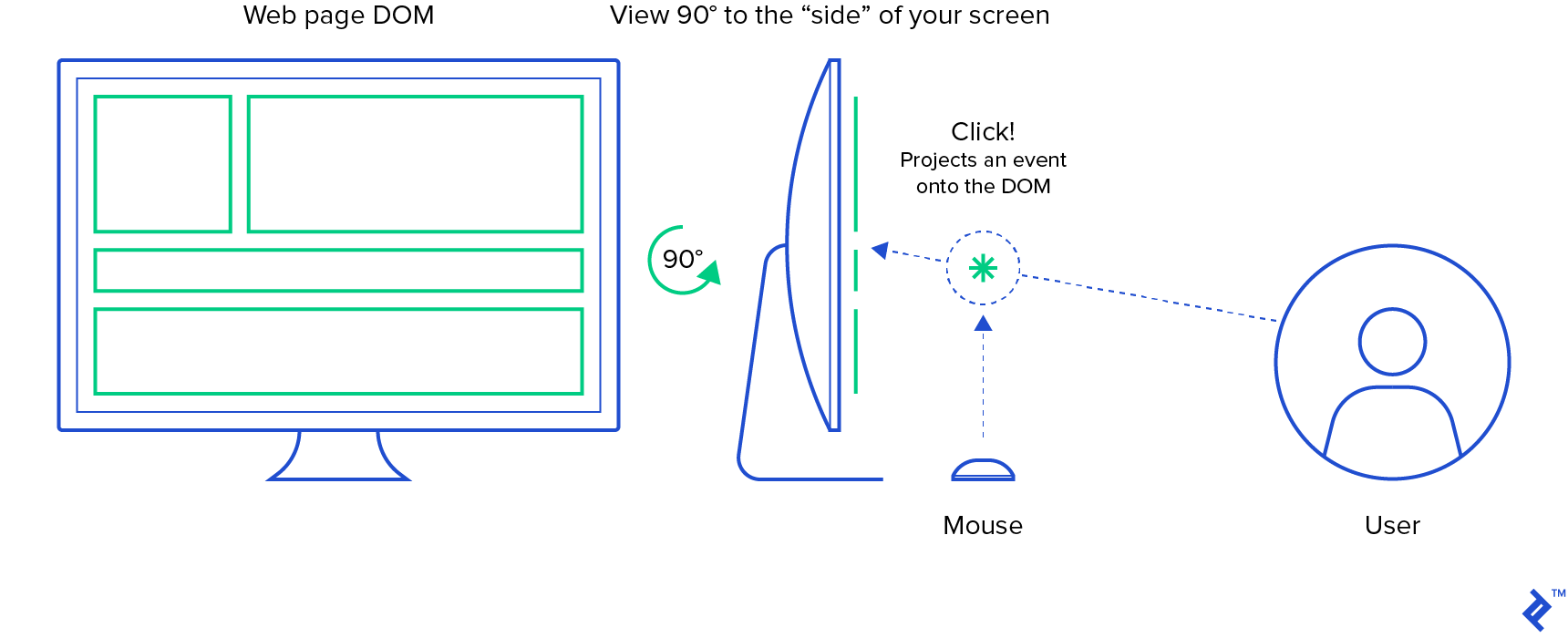

Those familiar with the browser DOM know it’s structured like a hierarchical tree.

Web design inherently assumes a frontal viewpoint. A side view would expose the DOM elements as lines, while a rear view would only reveal the <body> tag, obscuring its children.

VR’s immersive power lies in user agency—control over viewpoint, style, pace, and interaction order. No need to prioritize any specific element. However, programmatically manipulating the camera will induce nausea (VR sickness) in the user.

VR sickness is a real phenomenon. Our eyes and inner ears both detect motion, crucial for upright walking. Conflicting signals from these sensors trigger a natural response—vomiting—as the brain assumes ingestion of something disagreeable. We’ve all been there. This survival instinct has been extensively documented in VR literature. The free “Epic Fun” title on Steam, particularly the rollercoaster, provides a potent VR sickness demonstration.

Virtual Reality manifests as a “scene graph,” mirroring the DOM’s tree-like structure to manage complexity in a convincing 3D environment. Instead of scrolling and routing, we position the viewer as the focal point, drawing the experience toward them.

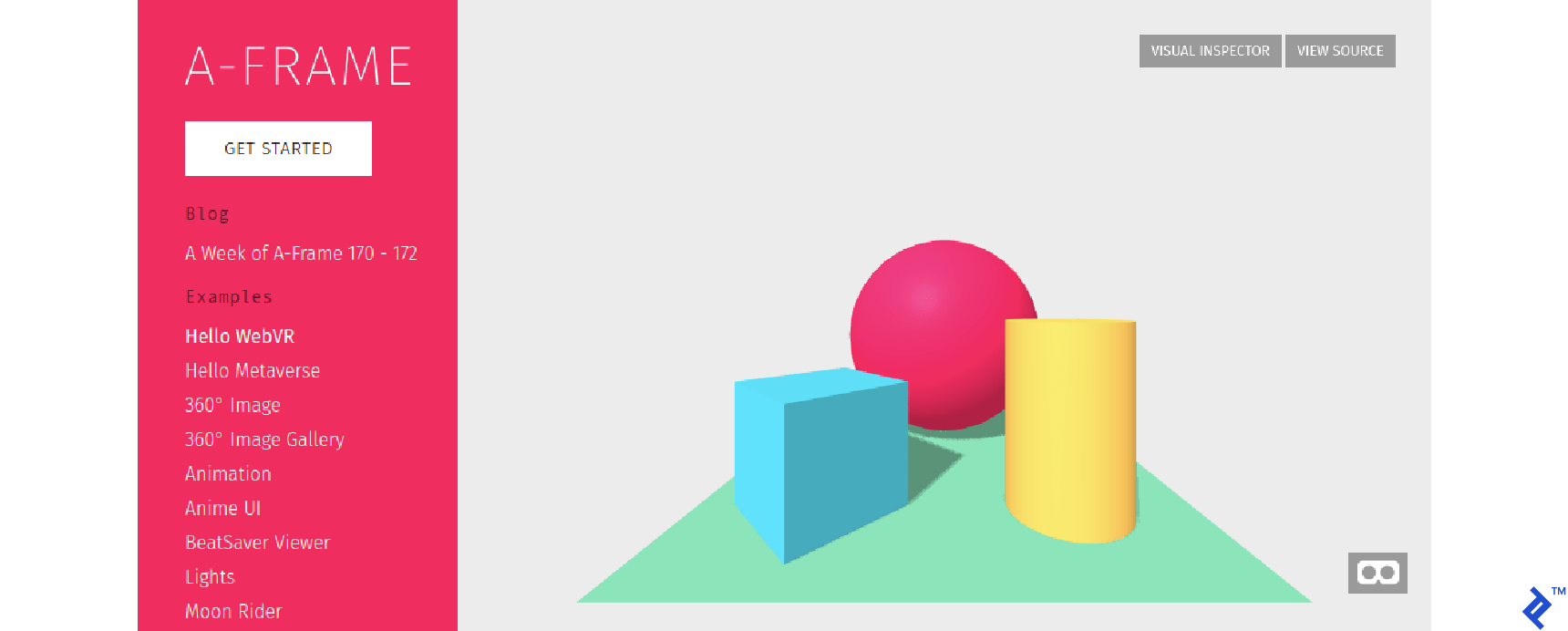

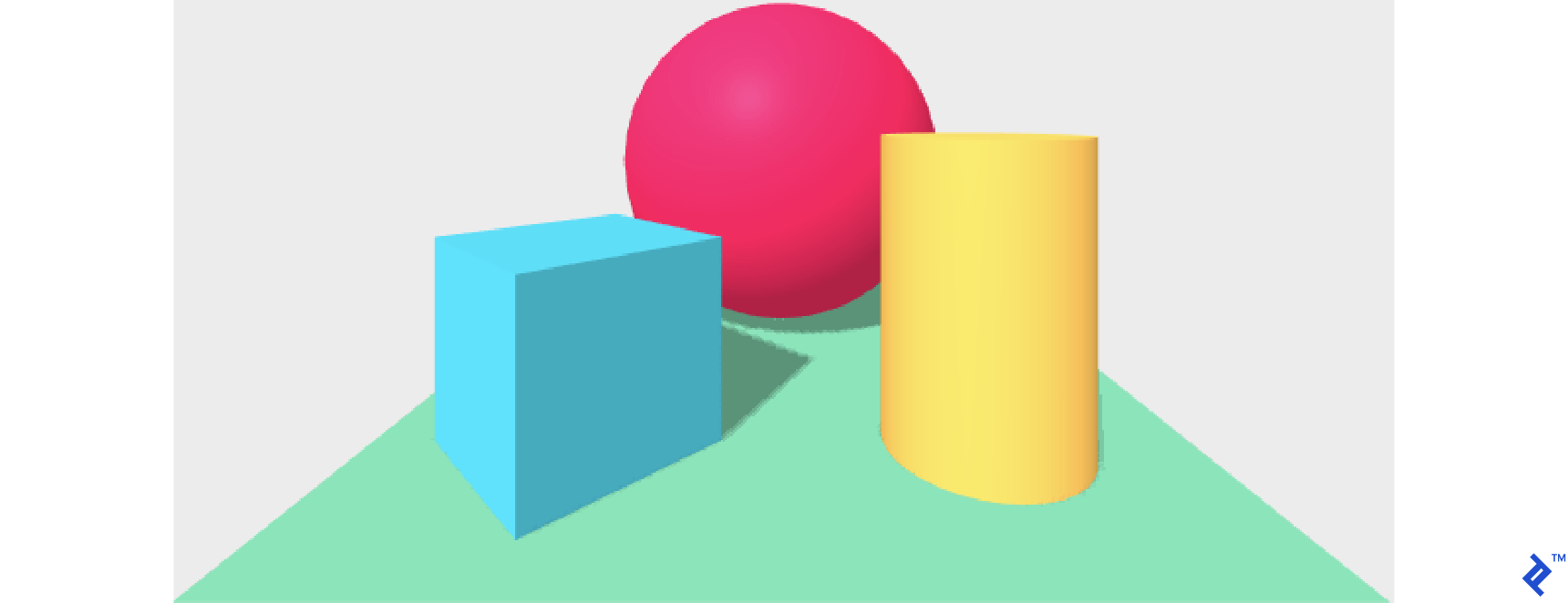

Let’s examine the quintessential “Hello World” scene graph from Google’s A-Frame WebVR Framework:

| |

This HTML document generates a browser DOM. The <a-*> tags belong to the A-Frame framework, with <a-scene> as the scene graph’s root. Here, we see four 3D primitives within the scene.

Initially, we perceive the scene through a flat-web browser. The lower-right mask allows users to switch to a 3D stereoscopic view.

Theoretically, you should be able to:

- Open this on your phone.

- Hold it up to your face.

- Immerse yourself in a new reality!

However, this typically requires the specialized lenses of a VR headset. Affordable VR headsets are available for Android phones (like those based on Google Cardboard), but for content development, a dedicated HMD (Head Mounted Display) such as Oculus Quest is recommended.

Similar to scuba diving or skydiving, Virtual Reality is an equipment-based experience.

The VR Designer’s Steep Learning Curve

Observe how A-Frame’s Hello World scene incorporates default lighting and camera settings:

- Differently colored cube faces indicate self-shadowing.

- A shadow cast by the cube onto the plane implies directional lighting.

- The absence of a gap between the cube and the plane suggests a world with gravity.

These subtle cues reassure the viewer that the device on their face isn’t entirely out of place.

Note that this default setup is implicit in the Hello World code. A-Frame thoughtfully provides sensible defaults, but this highlights a critical chasm flat-web designers must bridge—the world of camera and lighting.

We often take default lighting for granted. Consider buttons, for example:

The pervasiveness of implicit lighting is evident in design and photography. Even the “flat design” button can’t escape the web’s default lighting, casting a shadow down and to the right.

Mastering lighting and camera setups—designing, conveying, and implementing them—represents the steep learning curve for WebVR designers. The “Language of Film” encompasses cultural norms conveyed through various camera and lighting setups to evoke emotions and tell stories. In filmmaking, the professionals responsible for designing and maneuvering lights and cameras are called the [grip department](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grip_(job).

Back to Our Virtual Universe

Now, back to our celestial WebVR scene, which follows a similar structure:

| |

This HTML document loads the A-Frame framework and an interaction plugin. Our scene starts with <a-scene id="a-pocket-universe">.

We begin with <a-sky color="#222"></a-sky>, defining a background color for everything not explicitly defined within the scene.

Next, we create an “orbital plane” to ground the viewer as they navigate this unfamiliar world. It’s a simple disc with a small black sphere at coordinates (0,0,0). Without it, rotating felt disorienting:

| |

Now, we establish a collection to dynamically manage (add, remove, reposition) A-Frame entities.

| |

This acts as the stage for nBodyVisualizer’s paint(bodies) to work its magic.

Then, we define the relationship between the viewer and this world. This tech demo aims to showcase WebVR and its enabling technologies. A simple “astronaut” narrative injects playfulness, and a stellar signpost serves as a navigational reference point.

| |

This completes our scene graph. For a phone demo, I wanted some user interaction within this spinning world. How can we translate the “Throw Debris” button into VR?

Buttons, fundamental to modern design—where do they exist in VR?

Interactions in WebVR

VR has its own concept of “above and below the fold.” Initial interactions occur through the user’s avatar or camera, allowing movement and exploration.

On a desktop, WASD keys control movement, and the mouse handles camera rotation. While this facilitates exploration and information gathering, it doesn’t truly express user intent.

Real Reality has two key features often absent in the web:

- Perspective: Objects visually shrink as they recede.

- Occlusion: Objects are hidden or revealed based on their position.

VR simulates these features to create the illusion of 3D, and they can be leveraged to reveal information, interface elements, and even set the mood before interactions occur. Most people appreciate a moment to soak in the experience before proceeding.

In WebVR, interaction happens in 3D space. We have two primary tools:

- Collision: A passive 3D event triggered when objects occupy the same space.

- Projection: An active 2D function call identifying objects intersecting a line.

Collision: The Quintessential VR Interaction

In VR, a “collision” is self-explanatory: two objects occupying the same space trigger an event within A-Frame.

Emulating a button press requires providing the user with an object (a pawn) and a means to press it.

Unfortunately, WebVR can’t assume the presence of controllers. Many will experience it on desktops, phones (potentially as a stereoscopic view through Google Cardboard or Samsung Gear VR), lacking the ability to physically “touch” objects. Therefore, collisions must involve the user’s “personal space.”

We could assign players an astronaut-shaped pawn to move around, but forcing them into a chaotic swarm of planets feels jarring and contradicts our design’s sense of spaciousness.

Projection: Simulating 2D Clicks in 3D

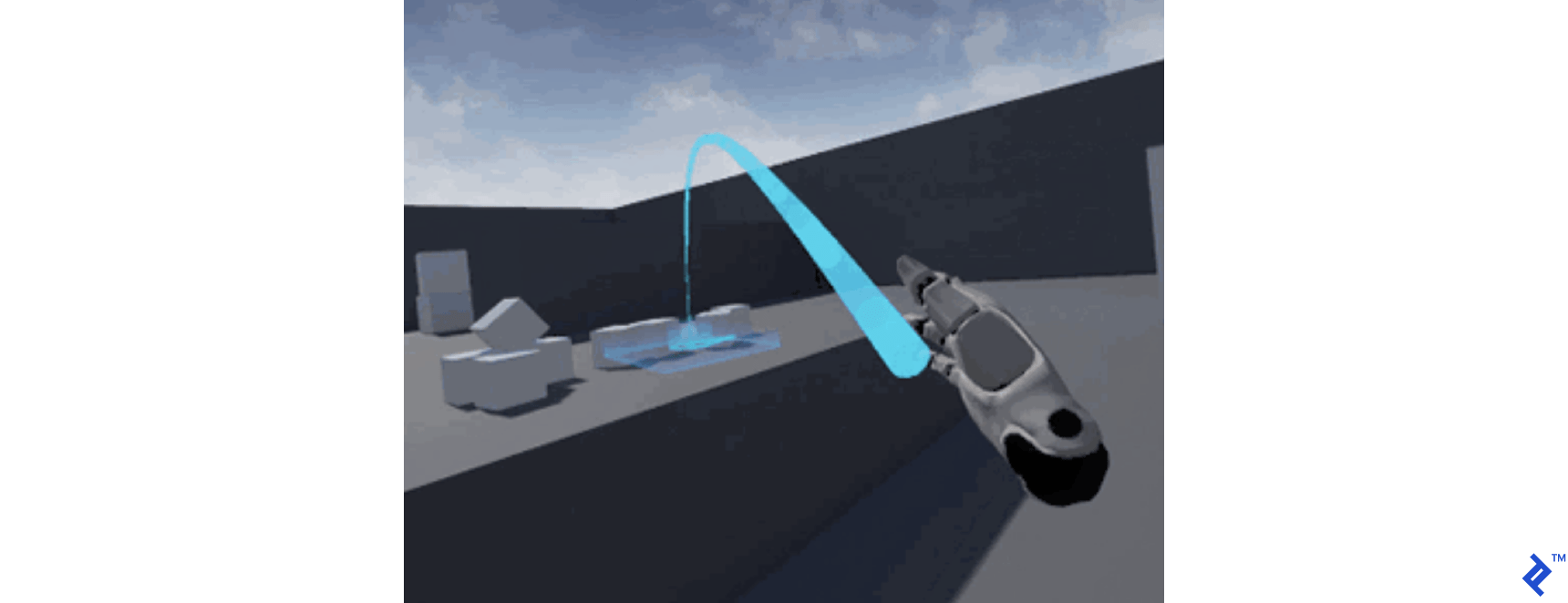

Besides collision, “projection” offers another avenue. Projecting a line through our scene reveals what it intersects. The “teleport ray” exemplifies this.

A teleport ray acts as a visual guide, indicating potential movement destinations. This “projection” searches for suitable landing spots, returning objects along its path. Here’s a teleport ray example:

Notice the ray’s downward-pointing parabolic shape, naturally intersecting the “ground” like a projectile and establishing a maximum teleportation range. Limits are crucial design considerations in VR, and reality offers plenty of natural constraints.

Projection effectively “flattens” the 3D world, allowing users to “click” objects like using a mouse. First-person shooters are essentially elaborate “2D click” games with frustratingly small hitboxes, often masked by intricate storylines.

The prevalence of guns in VR stems from their evolution into precise and reliable 3D mice, and “clicking” is a universally understood action requiring minimal learning.

Projection also maintains a safe distance between the user and the scene. Remember, approaching objects in VR naturally occludes others, potentially obscuring their significance.

Projection Without Controllers: Leveraging the “Gaze”

To achieve this interaction primitive without controllers, we can project the viewer’s “gaze” as a line-of-sight “cursor.” This cursor, visualized as a small blue circle, enables interaction with objects using a “fuse” mechanism—essentially, clicking with your eyes!

Think back to campfire stories: the more outlandish the tale, the less detail needed to sell it. Staring at the sun is a deliberately obvious and absurd “gaze” interaction. We use this “stare” to trigger the addition of new “debris” planets to the simulation. Surprisingly, no one has questioned this choice—VR has a disarming charm in its absurdity.

In A-Frame, the camera (representing the player’s invisible pawn) and this line-of-sight “cursor” are implemented as camera rigging. Nesting the <a-cursor> within the <a-camera> ensures the cursor inherits the camera’s transformations. Moving or rotating the camera also affects the gaze direction.

| |

The cursor’s “fuse” requires a full second of sustained “stare” before triggering an event.

With default lighting, you might notice the sun’s unlit “back.” I haven’t ventured outside the orbital plane, and I’m not sure that’s how suns actually work. However, for our tech demo’s stylized reality, it suffices.

Alternatively, embedding lighting within the camera element, moving with the user, would create a more intimate and potentially eerie asteroid miner experience. These are intriguing design choices.

The Integration Plan

We’ve established the integration points between the A-Frame <a-scene> and our JavaScript simulation:

A-Frame <a-scene>:

A designated collection for bodies:

<a-entity id="a-bodies"></a-entity>A cursor emitting projection events:

<a-cursor color="#4CC3D9" fuse="true" timeout="1"></a-cursor>

Our JavaScript simulation:

nBodyVisWebVR.paint(bodies): Manages (adds, removes, repositions) VR entities based on simulation data.addBodyArgs(name, color, x, y, z, mass, vX, vY, vZ): Introduces new debris bodies into the simulation.

index.html loads main.js, which initializes the simulation, much like the canvas version:

| |

We set the visualizer’s htmlElement to the a-bodies collection, which will contain the bodies.

Managing A-Frame Objects with JavaScript

With the scene declared in index.html, let’s implement the visualizer.

First, we configure nBodyVisualizer to read from the nBodySimulation bodies list and dynamically manage (create, update, delete) A-Frame objects within the <a-entity id="a-bodies"></a-entity> collection.

| |

The constructor stores the A-Frame collection, makes the simulation globally accessible for gaze events, and initializes an ID counter to synchronize bodies between our simulation and A-Frame’s scene.

| |

We loop through simulation bodies to establish labels and a lookup table for mapping A-Frame entities to their simulation counterparts.

Next, we iterate through existing A-Frame bodies, removing any culled by the simulation (for exceeding boundaries), enhancing perceived performance.

Finally, we loop through simulation bodies, creating new <a-sphere> elements for missing bodies and repositioning existing ones using aBody.object3D.position.set(body.x, body.y, body.z).

Manipulating A-Frame elements programmatically is achieved through standard DOM functions. Adding an element involves appending a string to the container’s innerHTML. This approach feels slightly unconventional but works, and I haven’t found a superior alternative.

Notice the ternary operator near “star” when creating the appended string to set an attribute.

| |

If the body is a “star,” we add attributes defining its events. Here’s how our star is represented in the DOM:

| |

Three attributes, debris-listener, event-set__enter, and event-set__leave, govern interactions and represent the final stretch of our integration.

Defining A-Frame Events and Interactions

We utilize the NPM package “aframe-event-set-component” within the entity’s attributes to change the sun’s color upon the viewer’s “gaze.”

This “gaze,” a projection from the viewer’s position and rotation, provides crucial feedback, indicating that their attention influences the environment.

Our star sphere now responds to two shorthand events enabled by the plugin: event-set__enter and event-set__leave:

| |

Next, we attach a debris-listener to our star sphere, implemented as a custom A-Frame component.

| |

A-Frame components are defined globally:

| |

This component acts like a “click” listener, triggered by the gaze cursor to introduce 10 new random bodies into the scene.

In summary:

- We declare the WebVR scene using A-Frame in standard HTML.

- JavaScript enables dynamic management (adding, removing, updating) of A-Frame entities.

- Interactions are created in JavaScript using event handlers through A-Frame plugins and components.

WebVR: We Came, We Saw, We Conquered

I hope this tech demo has been as insightful for you as it has been for me. The principles applied here (web workers and WebAssembly) extend beyond WebVR, holding promise for browser edge computing.

Virtual Reality is a technological tidal wave. If you recall the awe of holding your first smartphone, experiencing VR for the first time amplifies that feeling tenfold across all aspects of computing. It’s only been 12 years since the first iPhone.

VR has existed for much longer, but its widespread adoption hinges on technologies driven by the mobile revolution and Facebook’s Oculus Quest, not the PC.

The internet and open-source are testaments to human ingenuity. To everyone who contributed to the flat internet, I salute your vision and daring spirit.

We have the power to create, so let’s build worlds!