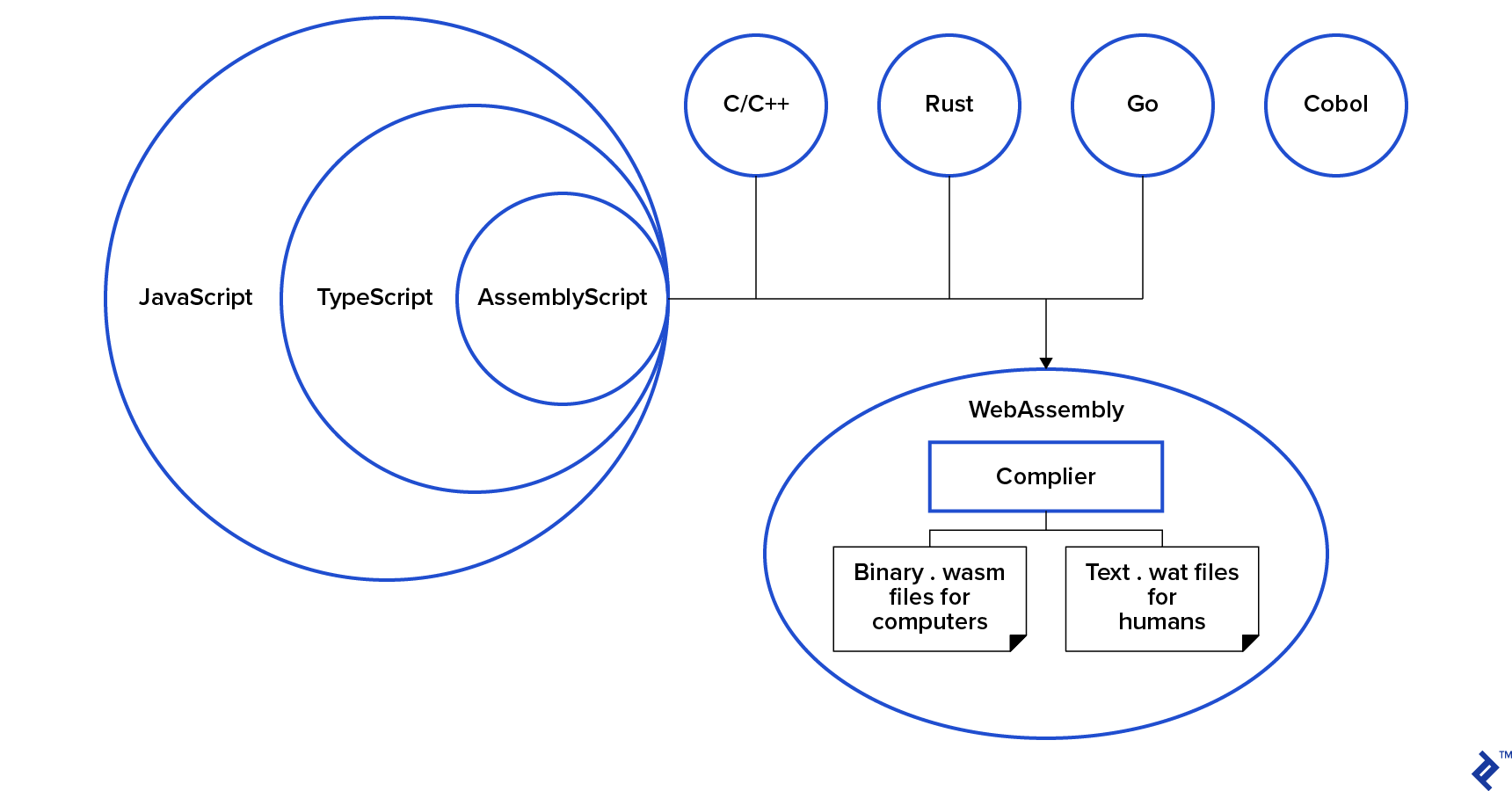

It’s undeniable that WebAssembly won’t be replacing JavaScript as the primary language for the web anytime soon.

“WebAssembly, or Wasm for short, is a binary instruction format designed for a stack-based virtual machine. Its purpose is to serve as a portable compilation target for high-level languages like C/C++/Rust, facilitating their deployment on the web for both client and server applications.” –WebAssembly.org

It’s crucial to understand that WebAssembly is not a programming language in itself. It operates more like an executable file (’.exe’) or, more accurately, a Java bytecode file (’.class’). Web developers compile their code from other languages into WebAssembly, which is then downloaded and executed by your browser.

Think of WebAssembly as borrowing features from other languages without fully committing to them, much like renting a boat or a horse for a specific purpose. It provides access to the strengths of other languages without requiring a complete shift in development practices. This allows the web to prioritize essential aspects such as feature delivery and user experience enhancement.

WebAssembly enjoys support from over 20 languages, including prominent ones like Rust, C/C++, C#/.Net, Java, Python, Elixir, Go, and even JavaScript itself.

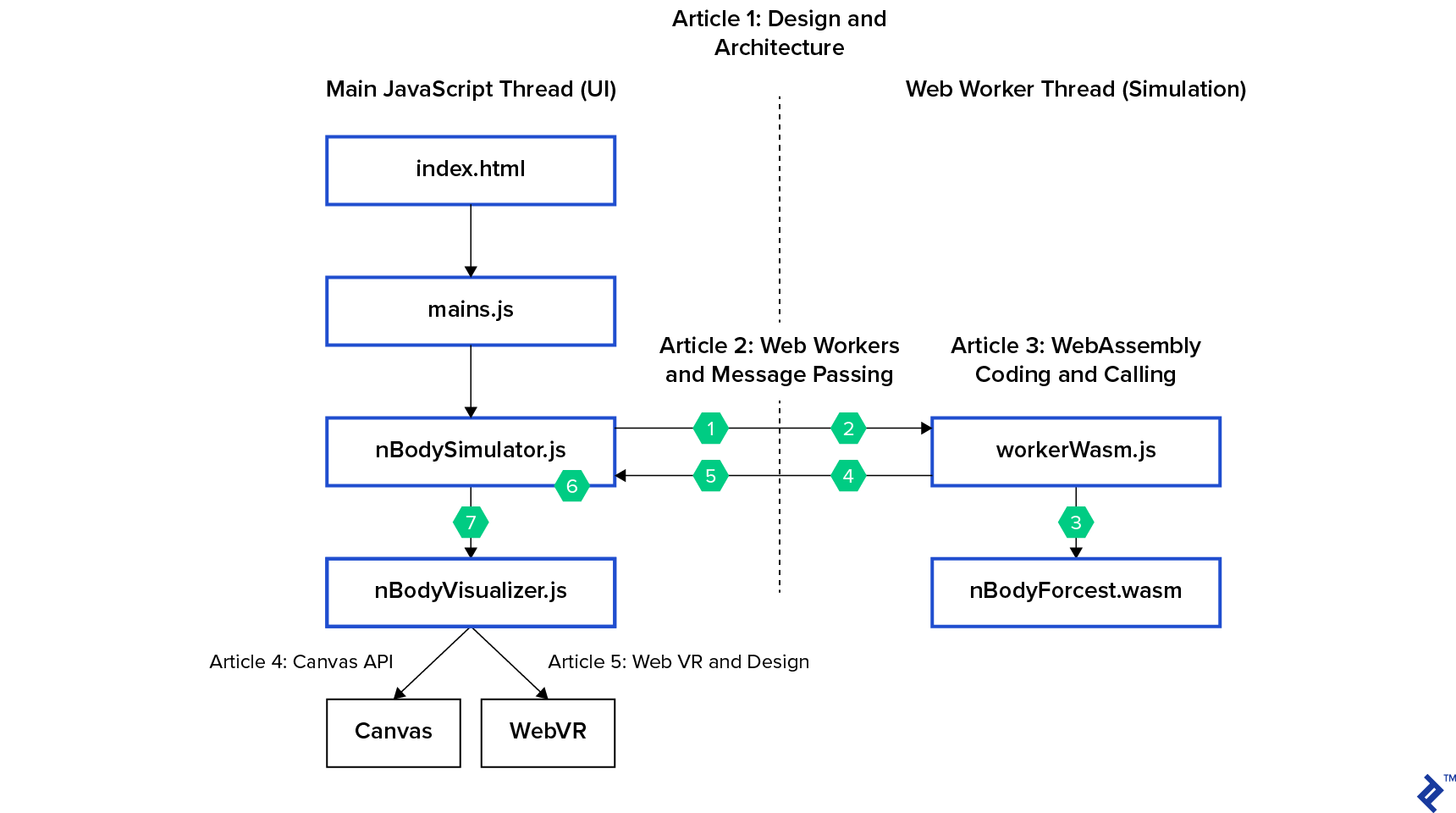

Recall the architecture diagram of our simulation; we offloaded the entire simulation process to nBodySimulator, which in turn manages the web worker.

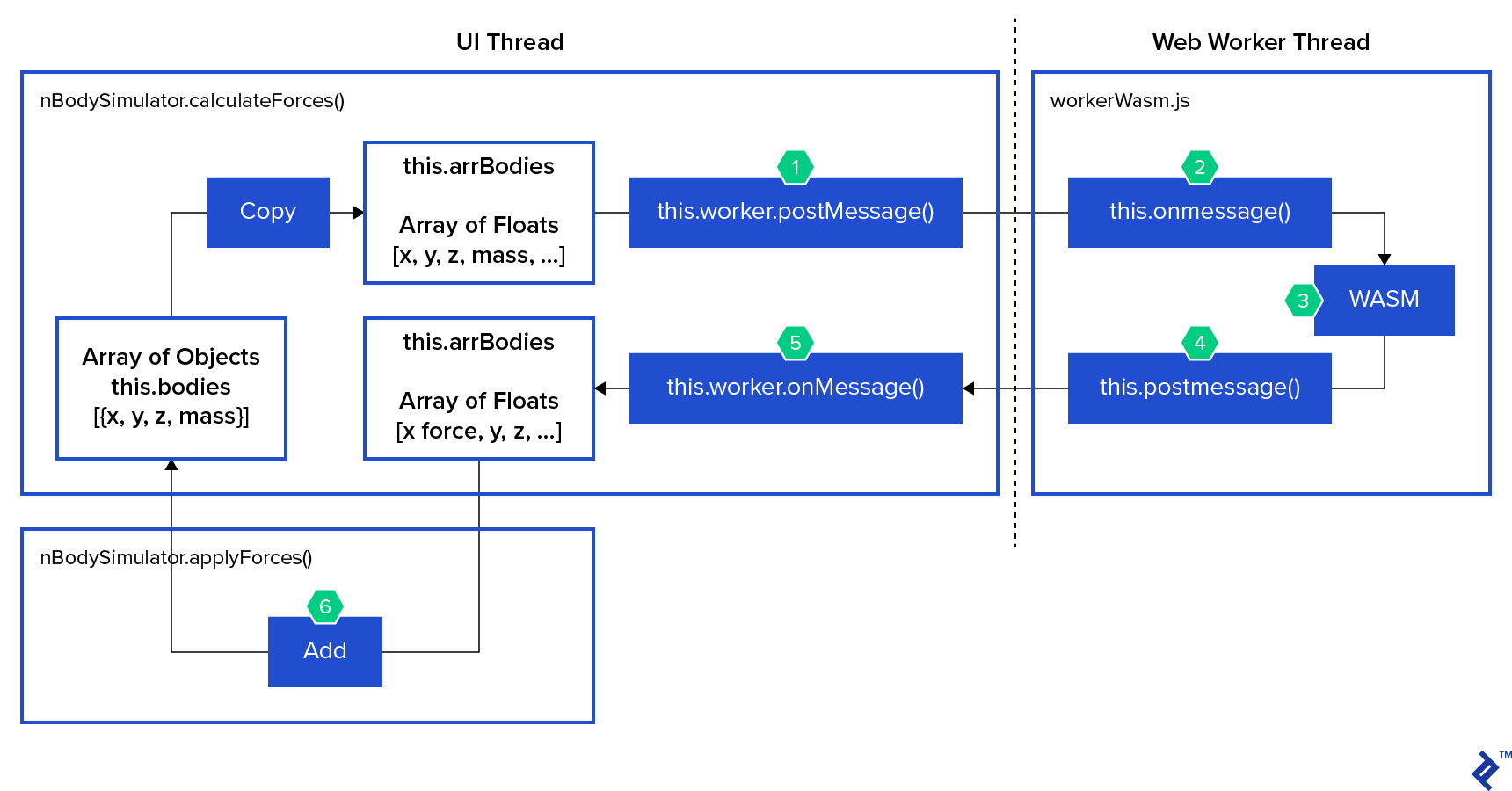

As highlighted in the introductory post, nBodySimulator has a step() function that is invoked every 33 milliseconds. Let’s break down the actions performed by the step() function, as depicted in the diagram:

- The

calculateForces() function within nBodySimulator initiates the calculation process by calling this.worker.postMessage(). - The

this.onmessage() function in workerWasm.js receives the message. workerWasm.js then synchronously executes the nBodyForces() function from the nBodyForces.wasm module.- Using

this.postMessage(), workerWasm.js sends the calculated forces back to the main thread. - The

this.worker.onMessage() function on the main thread receives and processes the returned data. - Subsequently,

nBodySimulator’s applyForces() function updates the positions of the bodies based on the received forces. - Finally, the visualizer performs a repaint to reflect the changes.

In the last installment, we developed the web worker responsible for encapsulating our WebAssembly computations. Today, we’ll focus on constructing the “WASM” component and handling data transfer in and out of it.

To maintain simplicity, I opted for AssemblyScript as the language for writing our computational logic. Being a subset of TypeScript, which itself is a typed superset of JavaScript, it should feel familiar.

Let’s illustrate this with an example. Consider an AssemblyScript function designed to compute the gravitational force between two bodies. The notation :f64 in someVar:f64 explicitly defines the someVar variable as a float for the compiler’s benefit. It’s crucial to remember that this code will be compiled and executed in an environment completely separate from JavaScript.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

| // AssemblyScript - a TypeScript-like language that compiles to WebAssembly

// src/assembly/nBodyForces.ts

/**

* Given two bodies, calculate the Force of Gravity,

* then return as a 3-force vector (x, y, z)

*

* Sometimes, the force of gravity is:

*

* Fg = G * mA * mB / r^2

*

* Given:

* - Fg = Force of gravity

* - r = sqrt ( dx + dy + dz) = straight line distance between 3d objects

* - G = gravitational constant

* - mA, mB = mass of objects

*

* Today, we're using better-gravity because better-gravity can calculate

* force vectors without polar math (sin, cos, tan)

*

* Fbg = G * mA * mB * dr / r^3 // using dr as a 3-distance vector lets

* // us project Fbg as a 3-force vector

*

* Given:

* - Fbg = Force of better gravity

* - dr = (dx, dy, dz) // a 3-distance vector

* - dx = bodyB.x - bodyA.x

*

* Force of Better-Gravity:

*

* - Fbg = (Fx, Fy, Fz) = the change in force applied by gravity each

* body's (x,y,z) over this time period

* - Fbg = G * mA * mB * dr / r^3

* - dr = (dx, dy, dz)

* - Fx = Gmm * dx / r3

* - Fy = Gmm * dy / r3

* - Fz = Gmm * dz / r3

*

* From the parameters, return an array [fx, fy, fz]

*/

function twoBodyForces(xA: f64, yA: f64, zA: f64, mA: f64, xB: f64, yB: f64, zB: f64, mB: f64): f64[] {

// Values used in each x,y,z calculation

const Gmm: f64 = G * mA * mB

const dx: f64 = xB - xA

const dy: f64 = yB - yA

const dz: f64 = zB - zA

const r: f64 = Math.sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy + dz * dz)

const r3: f64 = r * r * r

// Return calculated force vector - initialized to zero

const ret: f64[] = new Array<f64>(3)

// The best not-a-number number is zero. Two bodies in the same x,y,z

if (isNaN(r) || r === 0) return ret

// Calculate each part of the vector

ret[0] = Gmm * dx / r3

ret[1] = Gmm * dy / r3

ret[2] = Gmm * dz / r3

return ret

}

|

The function takes the (x, y, z, mass) properties of two bodies as input and returns a three-element float array representing the (x, y, z) components of the force vector they exert on each other. However, directly invoking this function from JavaScript is impossible as JavaScript lacks awareness of its existence. This necessitates “exporting” the function to JavaScript, leading us to our first technical hurdle.

Importing and Exporting in WebAssembly

In the realm of ES6, we handle imports and exports within JavaScript code using tools like Rollup or Webpack to ensure compatibility with older browsers that lack support for import and require(). This establishes a hierarchical dependency structure and unlocks advanced techniques such as “tree-shaking” and code-splitting.

However, in the context of WebAssembly, imports and exports serve purposes that differ from their ES6 counterparts. They primarily facilitate:

- Setting up a runtime environment for the WebAssembly module, including functions like

trace() and abort(). - Enabling the exchange of functions and constants between different runtime environments.

Observe the code snippet below. Notice how env.abort and env.trace are integral parts of the environment we must provide to our WebAssembly module. Meanwhile, functions like nBodyForces.logI are responsible for sending debugging messages to the console. Keep in mind that passing strings to and from WebAssembly is not straightforward since WebAssembly primarily deals with numerical types like i32, i64, f32, and f64, along with i32 references for abstract linear memory.

Note: It’s important to note that these code examples seamlessly switch between JavaScript (representing the web worker) and AssemblyScript (representing the WASM code).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

| // Web Worker JavaScript in workerWasm.js

/**

* When we instantiate the Wasm module, give it a context to work in:

* nBodyForces: {} is a table of functions we can import into AssemblyScript. See top of nBodyForces.ts

* env: {} describes the environment sent to the Wasm module as it's instantiated

*/

const importObj = {

nBodyForces: {

logI(data) { console.log("Log() - " + data); },

logF(data) { console.log("Log() - " + data); },

},

env: {

abort(msg, file, line, column) {

// wasm.__getString() is added by assemblyscript's loader:

// https://github.com/AssemblyScript/assemblyscript/tree/master/lib/loader

console.error("abort: (" + wasm.__getString(msg) + ") at " + wasm.__getString(file) + ":" + line + ":" + column);

},

trace(msg, n) {

console.log("trace: " + wasm.__getString(msg) + (n ? " " : "") + Array.prototype.slice.call(arguments, 2, 2 + n).join(", "));

}

}

}

|

Within our AssemblyScript code, we finalize the import of these functions as follows:

1

2

3

| // nBodyForces.ts

declare function logI(data: i32): void

declare function logF(data: f64): void

|

Note: Both the abort and trace functions are imported automatically.

Next, let’s export our interface from AssemblyScript. Here’s how we export some constants:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

| // src/assembly/nBodyForces.ts

// Gravitational constant. Any G could be used in a game.

// This value is best for a scientific simulation.

export const G: f64 = 6.674e-11;

// for sizing and indexing arrays

export const bodySize: i32 = 4

export const forceSize: i32 = 3

|

Now, we proceed to export the nBodyForces() function, which we intend to call from JavaScript. Observe how we export the Float64Array type at the beginning of the file. This enables us to utilize AssemblyScript’s JavaScript loader within our web worker for data retrieval (as demonstrated later):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

| // src/assembly/nBodyForces.ts

export const FLOAT64ARRAY_ID = idof<Float64Array>();

...

/**

* Given N bodies with mass, in a 3d space, calculate the forces of gravity to be applied to each body.

*

* This function is exported to JavaScript, so only takes/returns numbers and arrays.

* For N bodies, pass and array of 4N values (x,y,z,mass) and expect a 3N array of forces (x,y,z)

* Those forces can be applied to the bodies mass to update its position in the simulation.

* Calculate the 3-vector each unique pair of bodies applies to each other.

*

* 0 1 2 3 4 5

* 0 x x x x x

* 1 x x x x

* 2 x x x

* 3 x x

* 4 x

* 5

*

* Sum those forces together into an array of 3-vector x,y,z forces

*

* Return 0 on success

*/

export function nBodyForces(arrBodies: Float64Array): Float64Array {

// Check inputs

const numBodies: i32 = arrBodies.length / bodySize

if (arrBodies.length % bodySize !== 0) trace("INVALID nBodyForces parameter. Chaos ensues...")

// Create result array. This should be garbage collected later.

let arrForces: Float64Array = new Float64Array(numBodies * forceSize)

// For all bodies:

for (let i: i32 = 0; i < numBodies; i++) {

// Given body i: pair with every body[j] where j > i

for (let j: i32 = i + 1; j < numBodies; j++) {

// Calculate the force the bodies apply to one another

const bI: i32 = i * bodySize

const bJ: i32 = j * bodySize

const f: f64[] = twoBodyForces(

arrBodies[bI], arrBodies[bI + 1], arrBodies[bI + 2], arrBodies[bI + 3], // x,y,z,m

arrBodies[bJ], arrBodies[bJ + 1], arrBodies[bJ + 2], arrBodies[bJ + 3], // x,y,z,m

)

// Add this pair's force on one another to their total forces applied x,y,z

const fI: i32 = i * forceSize

const fJ: i32 = j * forceSize

// body0

arrForces[fI] = arrForces[fI] + f[0]

arrForces[fI + 1] = arrForces[fI + 1] + f[1]

arrForces[fI + 2] = arrForces[fI + 2] + f[2]

// body1

arrForces[fJ] = arrForces[fJ] - f[0] // apply forces in opposite direction

arrForces[fJ + 1] = arrForces[fJ + 1] - f[1]

arrForces[fJ + 2] = arrForces[fJ + 2] - f[2]

}

}

// For each body, return the sum of forces all other bodies applied to it.

// If you would like to debug wasm, you can use trace or the log functions

// described in workerWasm when we initialized

// E.g. trace("nBodyForces returns (b0x, b0y, b0z, b1z): ", 4, arrForces[0], arrForces[1], arrForces[2], arrForces[3]) // x,y,z

return arrForces // success

}

|

Delving into WebAssembly Artifacts: .wasm and .wat

When our AssemblyScript file (nBodyForces.ts) undergoes compilation into a WebAssembly nBodyForces.wasm binary, we have the option to generate a textual representation (.wat) that describes the instructions embedded in the binary.

Examining the contents of nBodyForces.wat, we can clearly see the imports and exports:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

| ;; This is a comment in nBodyForces.wat

(module

;; compiler defined types

(type $FUNCSIG$iii (func (param i32 i32) (result i32)))

…

;; Expected imports from JavaScript

(import "env" "abort" (func $~lib/builtins/abort (param i32 i32 i32 i32)))

(import "env" "trace" (func $~lib/builtins/trace (param i32 i32 f64 f64 f64 f64 f64)))

;; Memory section defining data constants like strings

(memory $0 1)

(data (i32.const 8) "\1e\00\00\00\01\00\00\00\01\00\00\00\1e\00\00\00~\00l\00i\00b\00/\00r\00t\00/\00t\00l\00s\00f\00.\00t\00s\00")

...

;; Our global constants (not yet exported)

(global $nBodyForces/FLOAT64ARRAY_ID i32 (i32.const 3))

(global $nBodyForces/G f64 (f64.const 6.674e-11))

(global $nBodyForces/bodySize i32 (i32.const 4))

(global $nBodyForces/forceSize i32 (i32.const 3))

...

;; Memory management functions we’ll use in a minute

(export "memory" (memory $0))

(export "__alloc" (func $~lib/rt/tlsf/__alloc))

(export "__retain" (func $~lib/rt/pure/__retain))

(export "__release" (func $~lib/rt/pure/__release))

(export "__collect" (func $~lib/rt/pure/__collect))

(export "__rtti_base" (global $~lib/rt/__rtti_base))

;; Finally our exported constants and function

(export "FLOAT64ARRAY_ID" (global $nBodyForces/FLOAT64ARRAY_ID))

(export "G" (global $nBodyForces/G))

(export "bodySize" (global $nBodyForces/bodySize))

(export "forceSize" (global $nBodyForces/forceSize))

(export "nBodyForces" (func $nBodyForces/nBodyForces))

;; Implementation details

...

|

Equipped with our nBodyForces.wasm binary and a web worker to execute it, we’re almost ready! However, we need to address the crucial aspect of memory management. To achieve seamless integration, we need to establish a mechanism for passing a variable-sized array of floats to WebAssembly and receiving a similar array back in JavaScript.

Initially, I approached this task with the naive assumption that I could effortlessly exchange these variable-sized arrays between JavaScript and a cross-platform, high-performance runtime environment. However, I quickly realized that passing data to and from WebAssembly presented the most unexpected challenge in this project.

Thankfully, the heavy lifting done by the AssemblyScript team came to my rescue. Their “loader” provided an elegant solution:

1

2

3

4

5

6

| // workerWasm.js - our web worker

/**

* AssemblyScript loader adds helpers for moving data to/from AssemblyScript.

* Highly recommended

*/

const loader = require("assemblyscript/lib/loader")

|

The presence of require() indicates the need for a module bundler like Rollup or Webpack. I chose Rollup for its simplicity and flexibility, and it proved to be an excellent choice.

Remember that our web worker, operating in a separate thread, essentially functions as an onmessage() function with a switch statement.

The loader helps us create our wasm module, conveniently providing additional memory management functions. Functions like __retain() and __release() handle garbage collection references within the worker’s runtime, __allocArray() copies our parameter array into the wasm module’s memory, and __getFloat64Array() retrieves the result array from the wasm module’s memory back into the worker’s runtime.

With this setup, we can now efficiently transfer float arrays to and from nBodyForces() and complete our simulation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

| // workerWasm.js

/**

* Web workers listen for messages from the main thread.

*/

this.onmessage = function (evt) {

// message from UI thread

var msg = evt.data

switch (msg.purpose) {

// Message: Load new wasm module

case 'wasmModule':

// Instantiate the compiled module we were passed.

wasm = loader.instantiate(msg.wasmModule, importObj) // Throws

// Tell nBodySimulation.js we are ready

this.postMessage({ purpose: 'wasmReady' })

return

// Message: Given array of floats describing a system of bodies (x,y,x,mass),

// calculate the Grav forces to be applied to each body

case 'nBodyForces':

if (!wasm) throw new Error('wasm not initialized')

// Copy msg.arrBodies array into the wasm instance, increase GC count

const dataRef = wasm.__retain(wasm.__allocArray(wasm.FLOAT64ARRAY_ID, msg.arrBodies));

// Do the calculations in this thread synchronously

const resultRef = wasm.nBodyForces(dataRef);

// Copy result array from the wasm instance to our javascript runtime

const arrForces = wasm.__getFloat64Array(resultRef);

// Decrease the GC count on dataRef from __retain() here,

// and GC count from new Float64Array in wasm module

wasm.__release(dataRef);

wasm.__release(resultRef);

// Message results back to main thread.

// see nBodySimulation.js this.worker.onmessage

return this.postMessage({

purpose: 'nBodyForces',

arrForces

})

}

}

|

Having covered all the necessary concepts, let’s recap our journey through web workers and WebAssembly, exploring the realm of the browser’s backend. Below are links to the corresponding code on GitHub:

- GET Index.html

- main.js

- nBodySimulator.js - This component sends a message to its designated web worker.

- workerWasm.js - This part handles the invocation of the WebAssembly function.

- nBodyForces.ts - This component is responsible for performing calculations and returning an array of forces.

- workerWasm.js - This part facilitates the transmission of the computed results back to the main thread.

- nBodySimulator.js - This component is responsible for resolving the promise associated with the forces.

- nBodySimulator.js - Finally, this part applies the received forces to the bodies and instructs the visualizers to update the display.

Moving forward, let’s shift our attention to building nBodyVisualizer.js. In the upcoming post, we’ll delve into creating a visualizer using the Canvas API. Finally, we’ll wrap up by integrating WebVR and Aframe.