This article is the second in a series exploring how to effectively use pydantic in Django projects. The first part focused on using pydantic’s Python type hints to improve the management of Django settings.

Developers often create inconsistencies between their development and production environments, leading to avoidable issues and increased workload. Maintaining consistent setups simplifies continuous deployment and streamlines the development process. To illustrate this, we’ll build a sample Django application using Docker, pydantic, and conda to create a consistent development environment.

A typical development environment consists of:

- A local version control repository.

- A Dockerized PostgreSQL database.

- A conda environment for managing Python dependencies.

Both simple and complex projects can benefit from using pydantic and Django. The following steps demonstrate a straightforward solution for environment mirroring.

Git Repository Configuration

Before diving into coding or system setup, we’ll initialize a local Git repository:

| |

We’ll begin with a basic Python .gitignore file placed in the repository’s root directory. This file will be updated throughout the tutorial, and we’ll later add files that should be excluded from Git tracking.

Django PostgreSQL Configuration Using Docker

Django, by default, utilizes SQLite; however, we generally prefer more robust databases like PostgreSQL for handling mission-critical data, especially due to SQLite’s limitations with concurrent user access. Maintaining the same database for development and production is crucial, aligning with the principles of The Twelve-factor App.

Fortunately, running a local PostgreSQL instance is effortless with the help of Docker and Docker Compose.

To keep our root directory organized, we’ll place Docker-related files in dedicated subdirectories. Let’s start by creating a Docker Compose file for deploying PostgreSQL:

| |

Next, we’ll create a docker-compose environment file to configure the PostgreSQL container:

| |

With the database server defined and configured, let’s start the container in the background:

| |

It’s important to highlight the use of sudo in the command above. This is necessary unless specific steps are implemented within our development environment.

Database Creation

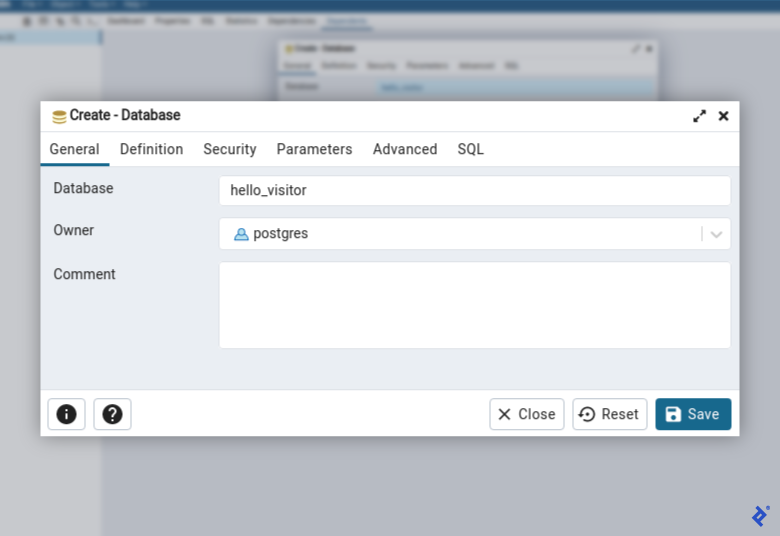

We’ll use a common toolset, pgAdmin4, to connect to and set up PostgreSQL, employing the same credentials defined earlier in the environment variables.

Now, let’s create a new database named hello_visitor:

With our database ready, we can proceed with setting up our programming environment.

Python Environment Management via Miniconda

We need an isolated Python environment with the necessary dependencies. We’ll use Miniconda for easy setup and management.

Let’s create and activate our conda environment:

| |

Now, create a file named hello-visitor/requirements.txt to list our Python dependencies:

| |

Next, instruct Python to install these dependencies:

| |

With the dependencies installed, we are prepared for application development.

Django Scaffolding

We’ll use django-admin to scaffold our project and app, followed by running the generated manage.py file:

| |

Next, configure Django to load our project. In the settings.py file, update the INSTALLED_APPS array to include our newly created homepage app:

| |

Application Setting Configuration

Following the pydantic and Django settings approach from the first installment, we need to create an environment variables file for our development environment. We’ll transfer our existing settings to this file as follows:

- Create

src/.envto store our development environment settings. - Copy settings from

src/hello_visitor/settings.pytosrc/.env. - Remove the copied lines from the

settings.pyfile. - Ensure the database connection string uses the previously configured credentials.

Our src/.env environment file should resemble this:

| |

Configure Django to read settings from environment variables using pydantic with this code:

| |

If you encounter issues after making these changes, compare your modified settings.py file with the version in our source code repository.

Model Creation

Our application will keep track of and show the number of times the homepage has been visited. To do this, we’ll need a model to store this count and then use Django’s object-relational mapper to initialize a single database row through a data migration.

First, let’s create the VisitCounter model:

| |

Next, initiate a migration to create the database tables:

| |

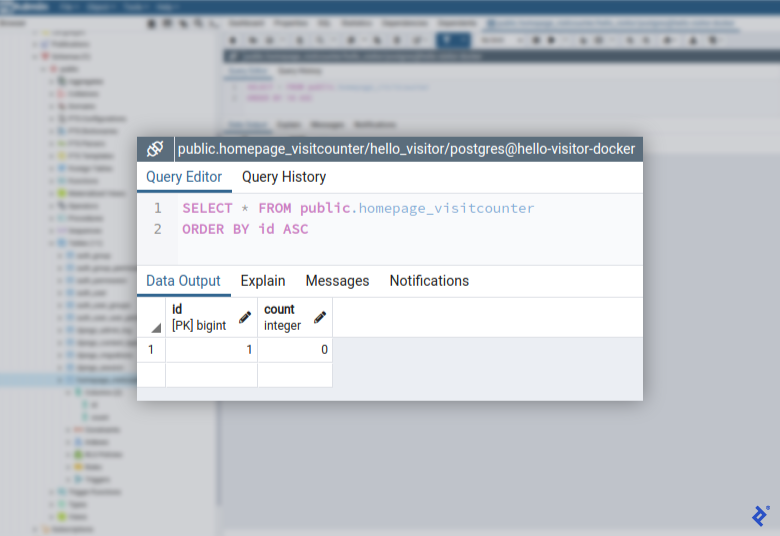

We can use pgAdmin4 to view the database and confirm the existence of the homepage_visitcounter table.

Now, let’s add an initial value to our homepage_visitcounter table. We’ll create a new migration file using Django’s scaffolding to achieve this:

| |

Modify the generated migration file to utilize the VisitCounter.insert_visit_counter method defined earlier:

| |

We can now execute this modified migration for the homepage app:

| |

By examining the contents of our table, we can ensure the migration was successful:

We can see that our homepage_visitcounter table exists and has an initial visit count of 0. With the database set up, we can move on to building the UI.

Create and Configure Our Views

Our UI implementation consists of two main components: a view and a template.

We’ll create the homepage view, which will be responsible for increasing the visitor count, saving it to the database, and passing the updated count to the template for display:

| |

Our Django application needs to handle requests directed at homepage. We’ll add the following file to configure this:

| |

To serve our homepage application, we need to register it in a separate urls.py file:

| |

The base HTML template for our project will reside in a new file, src/templates/layouts/base.html:

| |

We’ll extend the base template for our homepage app in a new file, src/templates/homepage/index.html:

| |

The final step in UI creation involves informing Django about the location of these templates. Let’s add a TEMPLATES['DIRS'] dictionary item to our settings.py file:

| |

With the user interface implemented, we’re almost ready to test the application. But first, let’s set up the final component of our environment: static content caching.

Our Static Content Configuration

To ensure consistency with our production environment, we’ll configure static content caching in our development system.

All static files for our project will be placed in a single directory, src/static, and Django will be instructed to collect these files before deployment.

We’ll use Toptal’s logo as the favicon for our application and store it as src/static/favicon.ico:

| |

Next, configure Django to collect static files:

| |

We only want to keep the original static files in the source code repository, excluding the production-optimized versions. Let’s add the latter to our .gitignore file:

| |

Now that our source code repository is correctly storing the necessary files, we can configure our caching system to handle these static files.

Static File Caching

To enhance the efficiency of serving static files for our Django application, we’ll utilize WhiteNoise in production, and consequently, in our development environment as well.

Register WhiteNoise as middleware by adding the following code snippet to the src/hello_visitor/settings.py file. The order of registration is critical, and WhiteNoiseMiddleware must be placed immediately after SecurityMiddleware:

| |

Static file caching should now be configured in our development environment, enabling us to run the application.

Running Our Development Server

With a fully coded application, we can launch Django’s built-in development web server using the following command:

| |

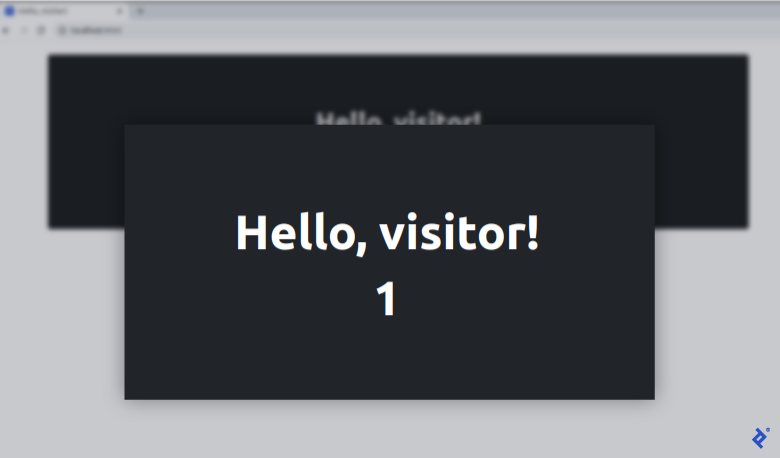

Each time we refresh the page at http://localhost:8000, the visit count will increment:

We now have a functioning application that tracks visits with each page refresh.

Ready To Deploy

This tutorial outlined the steps to create a functional application within a robust Django development environment that mirrors a production setup. Part 3 will delve into deploying our application to its production environment. In the meantime, you can explore additional exercises showcasing the advantages of Django and pydantic in the code-complete repository accompanying this pydantic tutorial.

The Toptal Engineering Blog expresses gratitude to Stephen Davidson for reviewing and beta testing the code samples presented in this article.