Next.js provides developers with tools that go beyond typical server-side rendering. By utilizing various configurations, software engineers can optimize their Next.js applications for peak performance. In practice, Next.js developers regularly implement a combination of caching strategies, diverse pre-rendering methods, and dynamic components. These techniques allow them to fine-tune and tailor Next.js rendering to align with specific project requirements.

Maintaining a balance between page load speed and optimal server load becomes particularly crucial when building large-scale, multi-page web applications with tens of thousands of pages. Selecting the appropriate rendering techniques is paramount in crafting a high-performance web app. Careful selection prevents the unnecessary consumption of hardware resources and helps avoid unnecessary costs.

Next.js Pre-rendering Techniques

While Next.js pre-renders all pages by default, developers can enhance performance and efficiency by leveraging different Next.js rendering types and approaches to pre-rendering and rendering. In addition to traditional client-side rendering (CSR), Next.js presents developers with a choice between two primary pre-rendering options:

Server-side rendering **(**SSR) generates web pages dynamically when a request is made. Although this approach increases server load, it’s essential for pages with dynamic content that need to be indexed by search engines and shared on social media.

Static site generation **(**SSG) focuses on rendering web pages during the build process. Next.js offers flexibility in static generation, allowing for generation with or without data, and includes automatic static optimization to determine if a page is suitable for pre-rendering.

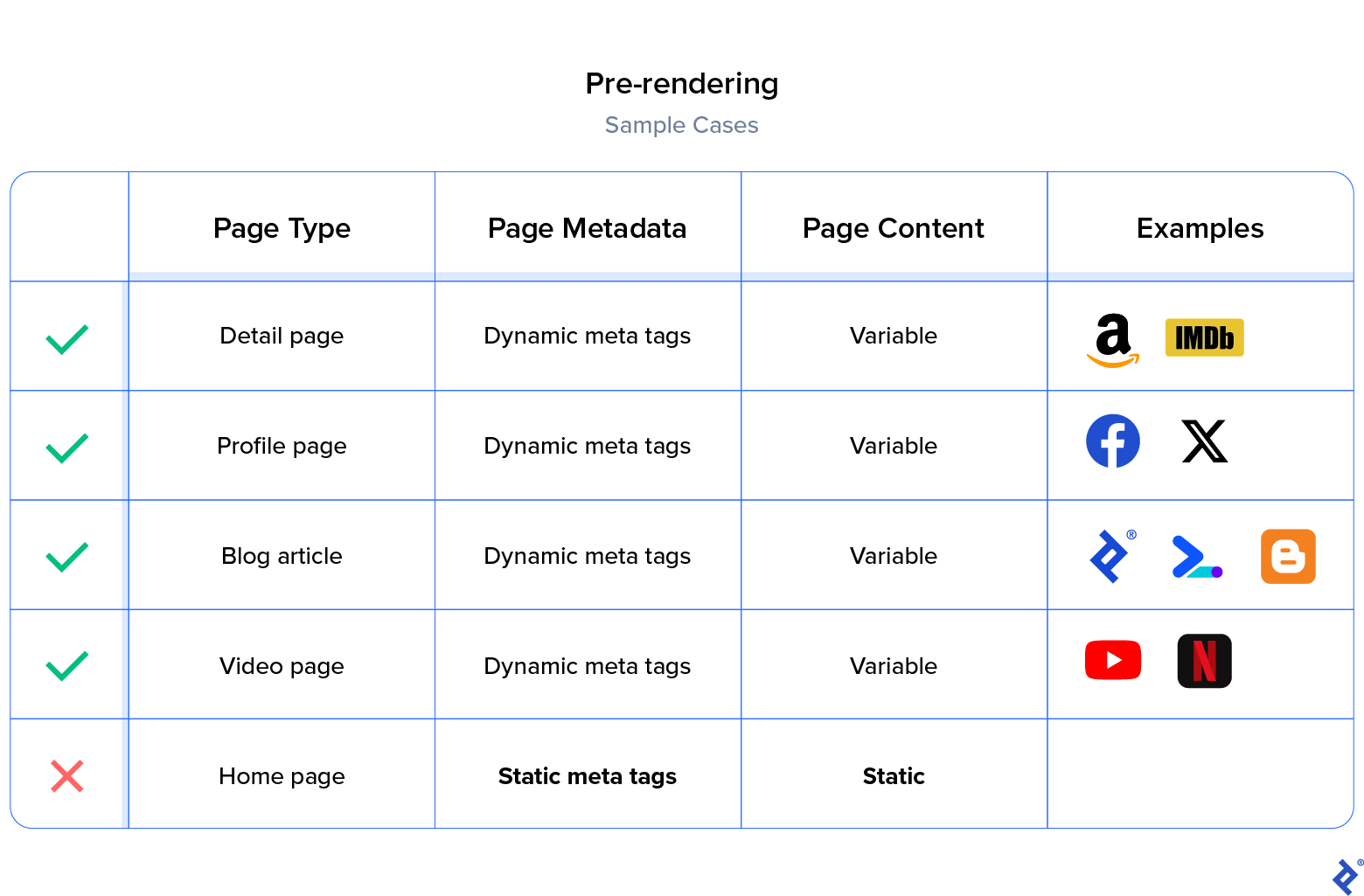

Pre-rendering proves beneficial for pages that require both social media visibility (Open Graph protocol) and strong SEO performance (meta tags) while containing dynamic content based on route endpoints. Consider an X (formerly Twitter) user profile page accessible via the /@twitter_name endpoint, where each page has unique metadata. In scenarios like this, pre-rendering all pages within the route is a recommended strategy.

Beyond metadata, SSR often outperforms CSR in terms of first input delay (FID), a Core Web Vitals metric measuring the time from a user’s initial interaction to the point when the browser can respond. Rendering large or data-intensive components on the client-side can lead to noticeable FID delays, especially for users with slower internet connections.

While prioritizing Next.js performance optimization, it’s crucial to avoid overloading the DOM tree on the server side, as this inflates the HTML document size. If content is located towards the bottom of a page and not immediately visible on the initial load, client-side rendering is a more efficient choice for that specific component.

By considering factors like variability, bulk size, and update/request frequency, we can further refine pre-rendering into several optimal methods. Choosing the right strategy requires a mindful approach to server load, aiming to prevent negative impacts on user experience and avoid unnecessary hosting expenses.

Determining the Factors for Next.js Performance Optimization

Just as traditional server-side rendering can strain the server at runtime, pure static generation might lead to a significant build-time load. Choosing the right rendering technique necessitates careful consideration of the nature of the webpage and route.

When fine-tuning Next.js for optimal performance, we have a variety of options at our disposal. When evaluating each route endpoint, it’s important to consider the following factors:

- Variability: This refers to the nature of the webpage’s content. Is it time-dependent (changing every minute), action-dependent (changing based on user actions like creating or updating content), or stale (remaining unchanged until the next build)?

- Bulk size: This factor considers the estimated maximum number of pages within that specific route endpoint. For instance, a streaming app might have 30 different genre pages.

- Frequency of updates: This refers to how often the content is expected to be updated, whether it’s time-dependent or action-dependent. For example, content might be updated 10 times a month.

- Frequency of requests: This represents the estimated rate of user or client requests to a particular webpage. For instance, a page might receive 100 requests per day or 10 requests per second.

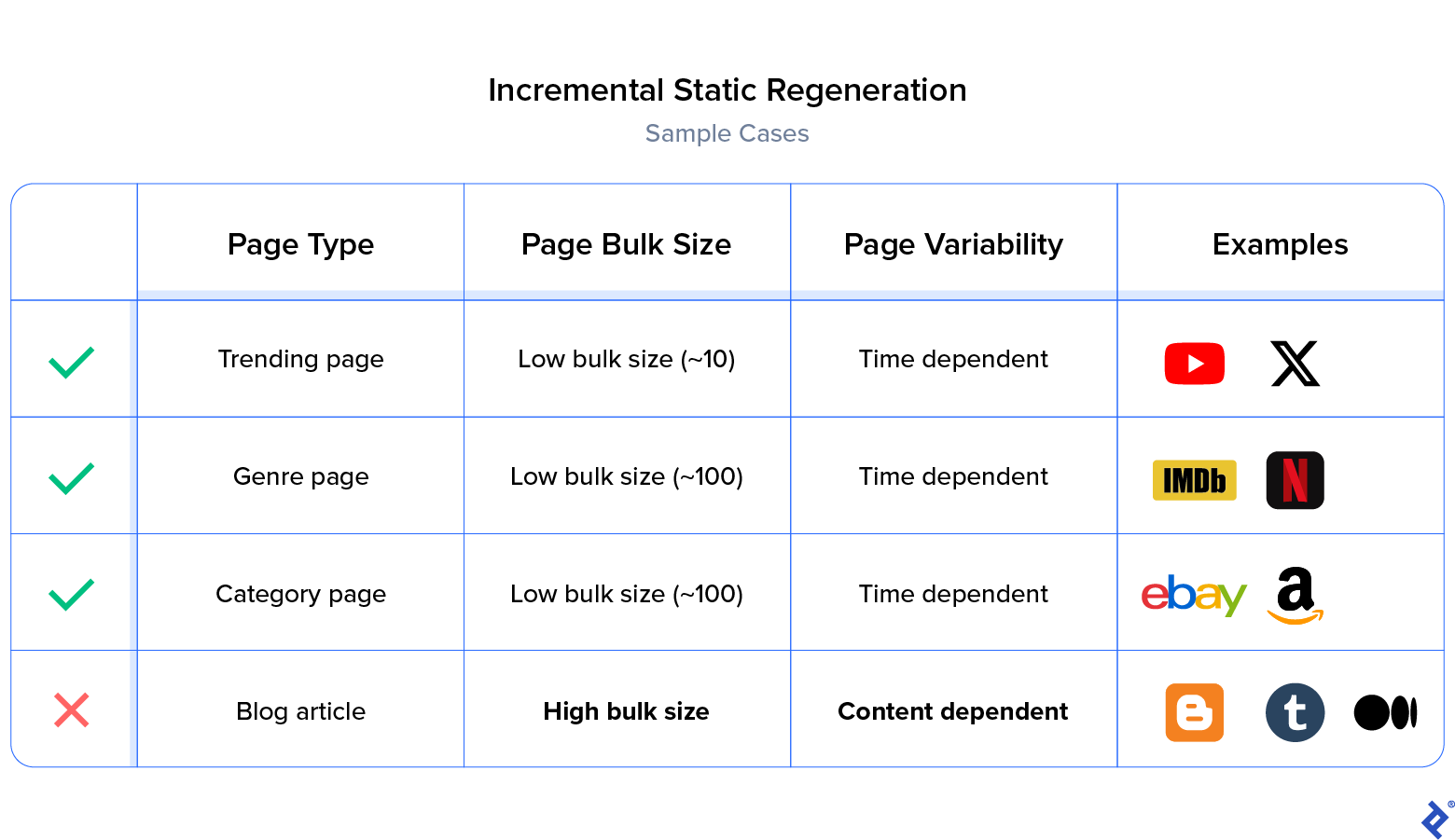

Low Bulk Size and Time-dependent Variability

Incremental static regeneration (ISR) is a technique where web pages are revalidated at a set interval. It is well-suited for standard website pages where data refreshes are expected at regular intervals. For instance, in a streaming app like Netflix, a genres/genre_id route point might require daily content refreshes for each genre page. Given the limited number of genres (around 200), ISR is an effective choice as it revalidates the page only if the cached or pre-built version is older than one day.

Here’s an example of how ISR is implemented:

| |

In this case, Next.js will revalidate these pages every 10 seconds at most. It’s essential to note that the revalidation isn’t continuous but triggered by incoming requests. Here’s a breakdown of how it works:

- A user requests a page that uses ISR.

- Next.js serves the cached (potentially outdated) page.

- Next.js checks if the cached page is older than 10 seconds.

- If the cached page is older, Next.js regenerates the page with fresh content.

High Bulk Size and Time-dependent Variability

Many server-side applications fall within this category. These pages, termed “public” pages, can be cached for a specific duration. Their content is not user-specific, and real-time data updates aren’t strictly necessary. In these situations, the sheer volume of pages (potentially around 2 million) makes generating them all at build time impractical.

SSR and Caching:

The optimal approach often involves server-side rendering (SSR) combined with caching. This means generating the webpage at runtime upon request on the server and caching it for a predetermined period (e.g., a day, hour, or minute). This ensures subsequent requests are served the cached page, preventing the need to generate millions of pages during the build or repeatedly generate the same page at runtime.

Let’s look at a basic example of implementing SSR with caching:

| |

If you’re interested in delving deeper into cache headers, you can find more information about Next.js caching documentation.

ISR and Fallback:

While generating millions of pages during the build process isn’t ideal, there are instances where having them in the build folder is necessary for configuration or custom rollbacks. In such cases, it’s possible to bypass page generation at build time and instead generate them on demand. This on-demand generation occurs either upon the first request or subsequent requests that exceed the stale age (revalidate interval) of the existing page.

To accomplish this, we start by including {fallback: 'blocking'} in the getStaticPaths function. When the build process begins, we disable or restrict access to the API, preventing the generation of any path routes. This effectively bypasses the unnecessary generation of millions of pages at build time, opting for on-demand generation at runtime. The generated pages are then stored in the build folder (_next/static) for future requests and builds.

Here’s an example of how to limit static generation during the build phase:

| |

Next, we want to cache the generated page for a set period and revalidate it once it becomes stale. The approach used for ISR earlier applies here as well:

| |

If a new request arrives after the 10-second interval, the page is revalidated. If the page hasn’t been built yet, it’s invalidated. This method effectively replicates the functionality of SSR with caching, but with the added step of storing the generated pages in the build output folder (/_next/static).

In most cases, SSR with caching proves to be the superior choice. ISR with fallback carries the potential drawback of initially displaying outdated information. Until a user visits a page to trigger revalidation, the content might be stale. While insignificant for some applications, this delay in displaying updated content can be unacceptable for others.

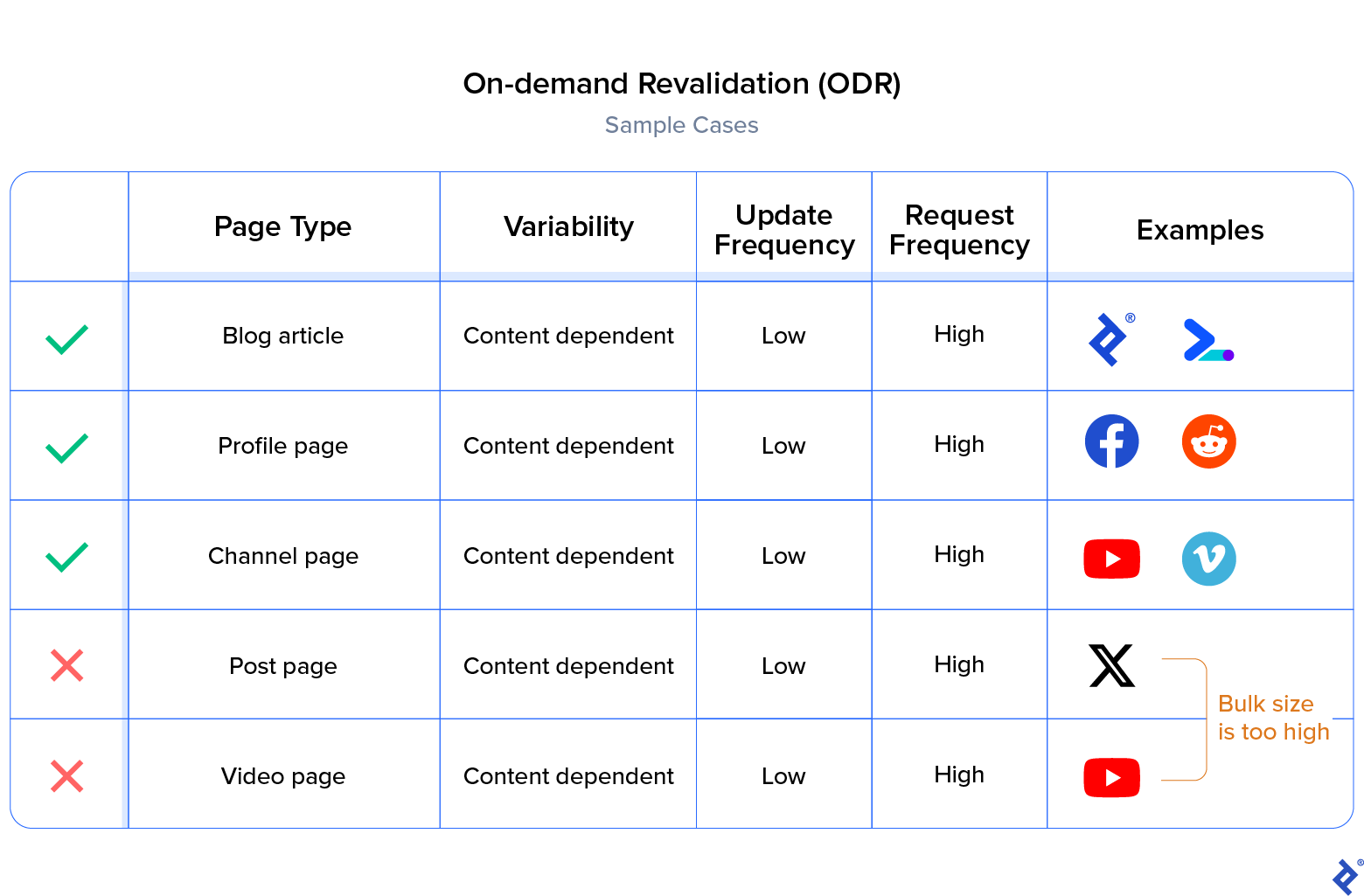

Content-dependent Variability

On-demand revalidation (ODR) offers a way to revalidate pages at runtime using webhooks. This technique is particularly useful for optimizing Next.js applications where content accuracy is paramount. Imagine building a blog with a headless CMS that provides webhooks triggered by content creation or updates. In such a scenario, you can call the corresponding API endpoint to revalidate the relevant webpage. The same principle applies to backend REST APIs; when a document is updated or created, a request can be sent to revalidate the page.

Here’s an example illustrating ODR in action:

| |

When dealing with exceptionally large datasets (e.g., around 2 million entries), it might be prudent to skip page generation during the build phase entirely. This can be done by passing an empty array of paths:

| |

By adopting this approach, we mitigate the issue encountered with ISR where users might initially see outdated content. With ODR, both User A and User B will see the most up-to-date information upon revalidation, and the regeneration process occurs in the background, independent of user requests.

There are instances where it’s beneficial to shift from content-dependent variability to time-dependent variability. This strategy proves useful when dealing with high bulk sizes or frequent updates or requests.

Let’s consider an example of an IMDB movie details page. While reviews and ratings might be updated frequently, real-time updates aren’t critical to the application’s functionality. Even an hour’s delay in reflecting updates is generally acceptable. In this case, switching to ISR significantly reduces server load as the movie details page doesn’t need to be updated every time a user submits a review. As a general rule, if the update frequency exceeds the request frequency, a transition to time-dependent variability might be advantageous.

With the release of React server components in React 18, Layouts RFC emerges as a highly anticipated feature update in Next.js. This update promises to bring support for single-page applications (SPAs), nested layouts, and a new routing system. The Layouts RFC further enhances data fetching, introducing parallel fetching, which allows Next.js to begin rendering before all data has been retrieved. Prior to this, with sequential data fetching, content-dependent rendering was only possible after completing the preceding fetch operation.

Next.js Hybrid Approaches With CSR

In Next.js, client-side rendering (CSR) always follows pre-rendering. Often viewed as a supplementary rendering type, CSR is particularly valuable in scenarios where minimizing server load or incorporating lazy loaded components is desired. The hybrid approach of combining pre-rendering with CSR offers advantages in numerous situations.

If the content is dynamic and doesn’t necessitate Open Graph integration, client-side rendering becomes a suitable option. For instance, we can employ SSG/SSR to pre-render a basic layout at build time and then populate the DOM after the component loads.

In cases like these, metadata generally remains unaffected. Consider the Facebook home feed, which updates every 60 seconds with variable content. The page’s core metadata (e.g., page title, home feed) remains constant, thus having no negative impact on the Open Graph protocol or SEO visibility.

Dynamic Components

Client-side rendering is well-suited for content that isn’t immediately visible within the browser window on initial load, such as components hidden by default until a user interaction occurs (e.g., login modals, alerts, dialog boxes). These components can be displayed by loading content after the initial render (if the rendering component is already in the JavaScript bundle) or by lazy loading the component itself through next/dynamic.

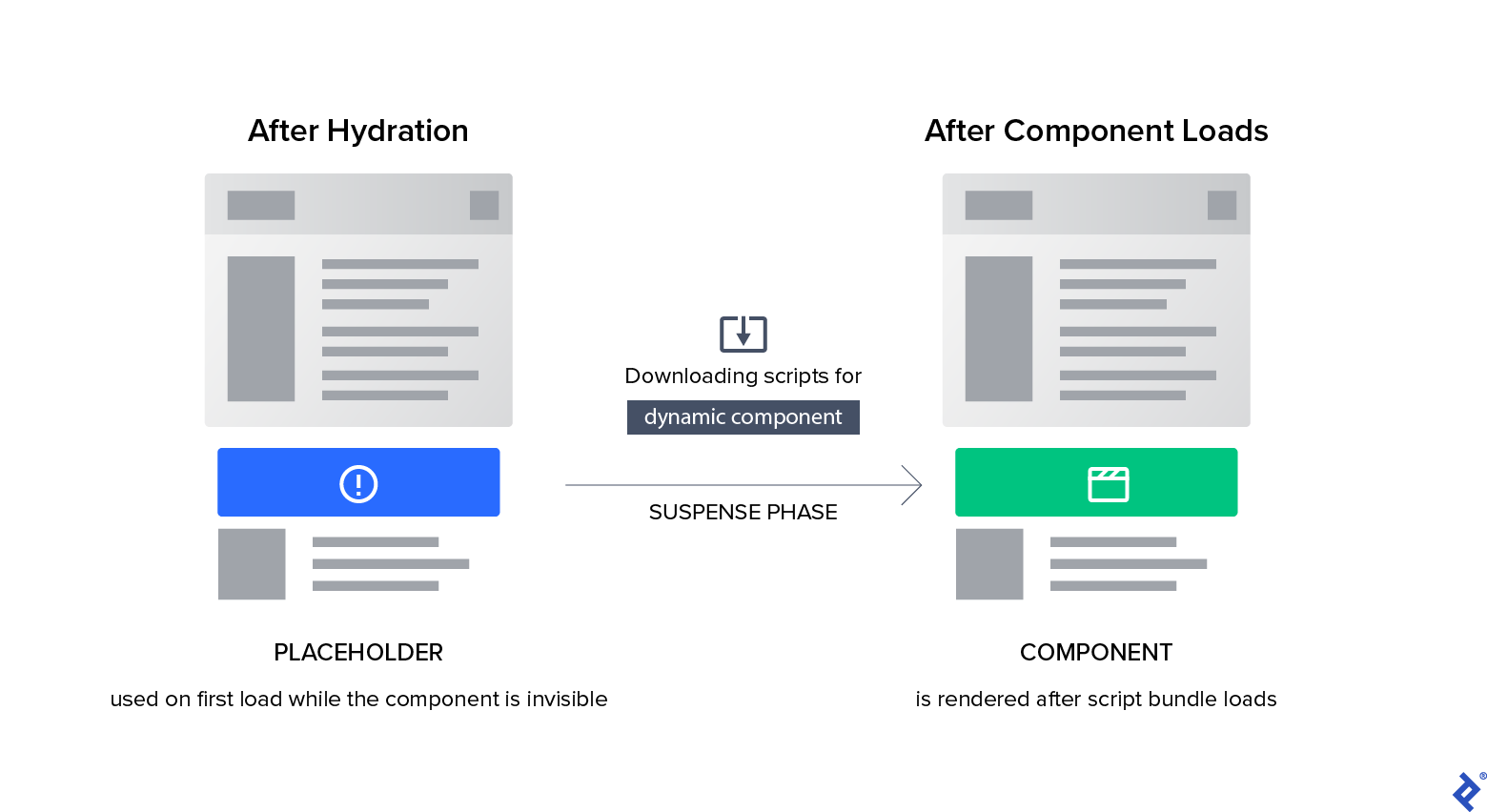

Typically, a website render starts with plain HTML, followed by hydration and client-side rendering techniques. These techniques might include fetching content when a component loads or using dynamic components.

Hydration is a process where React utilizes JSON data and JavaScript instructions to transform static HTML into interactive components. For example, it might attach event handlers to a button. However, this process can sometimes create the perception of a slower page load, as seen with empty X profile layouts where profile content loads progressively. Pre-rendering can mitigate this issue, especially when the content is readily available during the pre-rendering phase.

The suspense phase refers to the interval during which dynamic components are being loaded and rendered. Next.js provides the option to display a placeholder or fallback component during this phase.

Here’s an example of importing a dynamic component in Next.js:

| |

You can also render a fallback component while the dynamic component loads:

| |

It’s worth noting that next/dynamic includes a Suspense callback to show a loader or an empty layout while the component loads. This ensures that the header component is excluded from the page’s initial JavaScript bundle, resulting in faster initial load times. The Suspense fallback component will render first, followed by the Modal component once the Suspense boundary is resolved.

Next.js Caching: Tips and Techniques

When your goal is to enhance page performance and reduce server load simultaneously, caching becomes an invaluable tool. We’ve discussed how caching, especially in the context of SSR, can effectively improve availability and performance for routes with high bulk sizes. In Next.js, most assets, including pages, scripts, images, and videos, come with configurable cache settings that can be tailored to your specific requirements. Before delving into this further, let’s briefly review some fundamental caching concepts.

When a user accesses a website, the caching process for a webpage typically involves three main checkpoints:

- Browser Cache: This is the first line of defense. If a cached version of the requested resource exists, it’s served directly from the browser’s cache. If not, the request moves on to the next checkpoint.

- Content Delivery Network (CDN) Cache: CDNs store cached content on a network of servers distributed globally. This is also referred to as edge caching.

- Origin Server: If a resource isn’t found in the browser or CDN caches, the request reaches the origin server. Here, the resource is fetched and served. If the cache needs to be updated (i.e., the cached content is outdated), the origin server handles the revalidation.

Immutable assets served from /_next/static, such as CSS, JavaScript, images, and similar assets, automatically include caching headers:

| |

For Next.js server-side rendering, the caching behavior is managed by the Cache-Control header, which is set within the getServerSideProps function:

| |

In contrast, for statically generated pages (SSGs), the revalidate option within the getStaticProps function automatically generates the caching header.

Understanding and Configuring a Cache Header

While writing a cache header is generally straightforward, configuring it correctly requires an understanding of the various directives. Let’s break down the meaning of each tag:

Public vs. Private

The first crucial decision involves choosing between private and public. The public directive allows the response to be cached in shared caches like CDNs and proxy servers, while private restricts caching to the private cache (typically the user’s browser cache).

If a page is intended for a wide audience and its content remains consistent for all users, then public is the preferred choice. Conversely, if the page’s content is personalized for individual users, private should be used.

In practice, private is less common because developers often aim to leverage CDNs to cache their pages, which the private directive would prevent. Using private is generally reserved for pages containing user-specific or sensitive information that shouldn’t be stored in shared caches:

| |

Maximum Age

The s-maxage directive defines the maximum duration (in seconds) for which a cached page is considered fresh. Once this duration is exceeded, a revalidation occurs upon the next request. Although exceptions exist, s-maxage is suitable for a wide range of websites. The ideal value for s-maxage depends on your website’s analytics and how frequently the content is updated. For instance, if a page receives numerous daily hits but its content updates only once a day, a 24-hour s-maxage value is reasonable.

Must Revalidate vs. Stale While Revalidate

The must-revalidate directive enforces that a cached response can be reused only if it’s fresh. If the response is stale, it must be revalidated with the origin server. On the other hand, stale-while-revalidate allows a stale response to be reused for a specified duration while it’s being revalidated in the background.

Use must-revalidate when content updates are expected at specific intervals, rendering previous content invalid. For example, this directive would be suitable for a stock trading website where prices fluctuate frequently, making old data unreliable.

Conversely, stale-while-revalidate is appropriate when content updates occur periodically, but previous content, while outdated, isn’t entirely invalid. Consider a page showcasing the top 10 trending shows on a streaming platform. While this list might change daily, displaying slightly outdated content for a short period might be acceptable. The first user to request the page after the content update will trigger the revalidation process. This strategy is generally viable if the website traffic isn’t extremely high or if the content’s importance is relatively low. However, with high traffic, there’s a higher chance of numerous users seeing outdated content before the revalidation completes. As a rule of thumb, stale-while-revalidate is best suited for non-critical content updates.

You can control the duration for which stale content is served based on the content’s priority. A common duration is 59 seconds, as most pages take up to a minute to rebuild:

| |

Stale If Error

Another useful configuration is stale-if-error:

| |

This directive sets a time limit for how long a stale response can be used if a page rebuild fails, for example, due to a server error.

The Future of Next.js Rendering

It’s important to remember that no single perfect configuration fits all scenarios. The optimal approach often depends on the specific nature of your application. Start by carefully analyzing the factors we’ve discussed and select the Next.js rendering type and techniques that align best with your project’s needs.

Pay close attention to cache settings, especially when dealing with applications that experience high user traffic or page views. Large-scale applications with dynamic content generally benefit from shorter cache durations to ensure better performance and reliability. Conversely, smaller applications might not require such frequent cache refreshes.

While the techniques covered in this article provide a comprehensive toolkit for most scenarios, it’s important to stay informed about new features and updates regularly released by Vercel for Next.js. For instance, the introduction of the app router feature in Next.js 13 brings its own set of performance considerations. Continuous learning and adaptation to the evolving landscape of Next.js are crucial for maintaining optimal performance.