The excitement and challenges of keeping up with technology are ever-present for developers. New tools and advancements constantly emerge, sparking discussions in various tech communities. However, it’s crucial to remember that the heart of this community lies in the people, not just the technology. This realization prompts us to delve into the social dynamics within the developer world.

Recently, at Toptal, we engaged in insightful discussions regarding women’s contributions to open source and the potential factors limiting their involvement. Intrigued by these conversations with Breanden Beneschott and Bozhidar Batsov, I was particularly struck by a thought: Bozhidar](https://github.com/bbatsov) is one of the top [open source contributors on GitHub. Where am I? If you check my public GitHub account as of today, it is mainly small test projects that I used in class for my students. They are half-baked, and definitely not representative of my skills or expertise. (You will have to take my word on this.) If someone were to consider hiring me based on what they can find in that account, I guess I would have a hard time making a living. Still, I have been a professional developer for more than 20 years, and in my everyday job I’ve been using more open source software than I care to remember. Over time, I have hacked the Linux kernel to bend it to some specific need, tweaked every router and NAS that I bought, patiently waited for months in the Raspberry Pi waiting list to get my hands on it and get my home-made domotics as I like it. Still, none of these tweaks and tests ever made it to my GitHub to become open source. Also, aside from fixing a bug in one of the first versions of Tomcat, I never contributed to an open source project. Curious, isn’t it?

You might assume it’s due to a lack of time or interest, but I can assure you it’s not that simple. While I may have convinced myself that my personal projects wouldn’t be of interest to others, the truth is the prospect of sharing my work publicly on platforms like GitHub, for all to see and critique, deeply intimidated me. And even though you can delete personal projects from GitHub, contributing to a well-established open source project feels permanent and irrevocable. What if my code isn’t good enough? What if I’ve misinterpreted the problem? What if my pull request is rejected? What if I’m subjected to online criticism?

Conversations with fellow developers, many of whom were women, quickly revealed that I wasn’t alone in this feeling. However, as an engineer, I believe there are no problems without solutions.

Addressing this is vital because contributing to open source projects can have a significant impact:

- Career Impact: Many clients will scrutinize your online presence before offering you a job; your GitHub, LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter profiles are all carefully considered. Make sure you are using these platforms to your advantage.

- Technical Skill Development: Examining code written by others, particularly experienced developers, provides invaluable learning opportunities. Deciphering poorly written code presents its own set of challenges and lessons.

- Soft Skill Enhancement: Open source projects thrive on collaboration. Learning to work effectively within a team, leveraging shared tools and communication channels, is what distinguishes a skilled developer from a truly exceptional one.

- Community Contribution: Every contribution, no matter how small, benefits open source projects. Even fixing a minor typo in documentation enhances the final product.

- Network Expansion: While sending out numerous resumes is common, personal connections often prove more effective. Active participation in open source projects facilitates networking opportunities, allowing you to connect with others, earn their respect, and build a strong professional reputation.

This is my personal journey in overcoming this fear, and sharing it is an integral part of that journey. I hope that my experience will inspire others who may be hesitant to write a blog post or make even a small contribution. I want them to know that the fear, in the end, was unfounded. Additionally, for those interested in open source but unsure of where to begin, I will provide some basic guidance.

Understanding Open Source Software and Where to Find It

Open source software, often shortened to OSS, is any software whose source code is publicly available and licensed for modification and redistribution. It can be found on websites, distributed through mailing lists, or even delivered in more unconventional ways. Most commonly, the code is hosted in a collaborative repository. While there are other options like SourceForge and Bitbucket, our focus here is on GitHub. GitHub is user-friendly, boasts a large community, supports various programming languages and development environments, and is widely used for both open source and closed source projects. Familiarizing yourself with GitHub is a valuable skill, as your future client projects may be hosted there.

What If I’m Still Learning to Code?

If you’re reading this, you’re likely interested in learning to code. Thankfully, there are fantastic resources available online, both free and paid. It’s best to pick one language to focus on initially. If you have no preference, JavaScript is a great choice—you can get started directly in your web browser, and it’s in high demand. Personally, I favor Python, which is versatile for web development and scientific applications. You’ll find excellent courses on platforms like Coursera, Khan Academy, and PluralSight.

What If I’m Not Familiar with Git?

Knowing Git is crucial, so I encourage you to take a Git class, even if you have some experience. You might be surprised by how much you can still learn. If you can’t confidently explain the rebase command or if the idea of a mismanaged rebase makes you nervous, a Git class would be beneficial. Personally, I completed the entire Git path on Code School, but many other platforms offer excellent Git courses.

How Do I Choose a Project on GitHub?

A good starting point is to explore the open-source projects behind the tools and frameworks you use regularly. By diving into their codebases, you’ll deepen your understanding of how they work. If there’s a specific technology or tool you’re passionate about, look for projects related to it or even the tool’s own project. Alternatively, GitHub Showcases, categorized by area of interest, can provide inspiration.

For instance, a quick GitHub search for “Raspberry” yields over 17,000 repositories. To narrow your search, prioritize projects with a sizable, active community and effective issue tracking. When evaluating a project, consider:

- Contributors: Aim for projects with ten or more contributors, as this indicates substantial interest. If you’re new to open source or still developing your skills, it’s best to stick with projects with no more than fifty contributors, as larger communities often involve larger, more complex codebases.

- Commits: Look for projects with at least a thousand commits and recent activity (within the past week). In the fast-paced world of OSS, a month of inactivity suggests a project has become stagnant, and you might not receive timely responses. Daily activity is a positive sign.

- Issues: Issues represent open problems, reported bugs, or feature requests. They offer a starting point for contribution and indicate the level of activity within the project.

Pay attention to the project’s primary programming language, which is usually displayed in the project page’s top bar. Take time to gauge the community’s tone by reading through discussions and comments. Some projects are known for their less-than-welcoming communities, which might not be ideal for beginners.

I selected ScyllaDB, a columnar data storage project. Having an interest in all things data and performance-related, I was drawn to it. Despite never having worked with it before, I felt confident I could navigate its codebase. While working with familiar tools might seem easier, I saw this as a challenge and an opportunity to learn something new. The project met all my other criteria: 18 contributors, 6,500 commits (the most recent one being 23 hours old at the time of writing), 178 open issues, and a very active community.

Taking the First Steps

Begin by cloning the repository and setting up the software locally. Familiarize yourself with its components. Then, delve into the issues list. Once you feel comfortable, attempt to replicate the issue on your machine to understand the source of the problem.

Alternatively, identify areas you can directly improve or modify, such as typos or formatting issues. I decided to fix a minor bug: an incorrect variable name within a script’s documentation.

While this may seem trivial, inaccurate documentation can be more detrimental than no documentation at all. Users rely on installation scripts and documentation; inaccurate information can lead to considerable frustration. Fixing this bug aligned well with my current skill set. It required me to work through the entire process and gain a degree of familiarity with the codebase. While bug fixing may not always be glamorous, it’s an excellent way to get your feet wet in a new project.

Creating a Fork

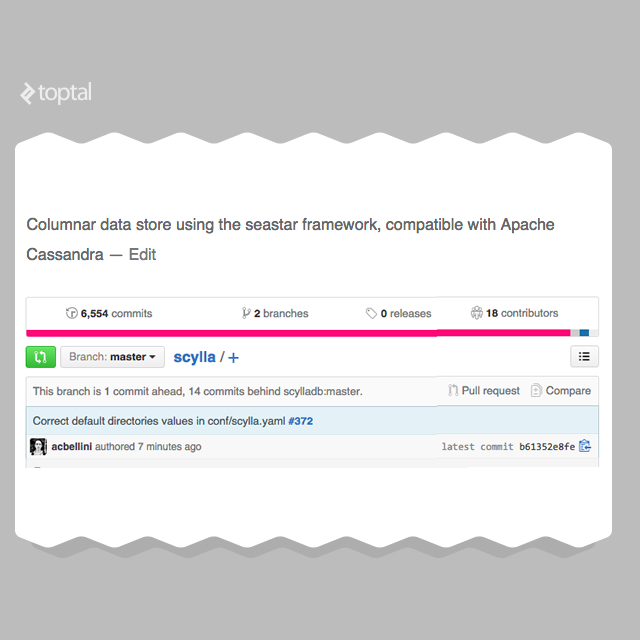

While this might seem obvious, I want to emphasize that I was a nobody to the ScyllaDB project. Granting me direct access to modify their codebase would be risky. Instead, I needed to create a “fork” within my own GitHub account. Here is my ScyllaDB fork. This serves as my personal sandbox where I have complete control over the code. If I wanted to create a modified version of ScyllaDB for a completely different purpose, I could do so here. Creating a fork is simple: navigate to the project’s main page on GitHub and click the “Fork” button. Not scary at all, right?

Time to Tackle the Bug

Now comes the time to test the code locally and implement the necessary changes. Ensure you have the Git client installed on your machine. Then, add your SSH public key to GitHub and verify it’s loaded in your ssh-agent. Cloning the code locally is straightforward; simply point your git clone command to your forked repository instead of the main branch:

| |

Assuming you’ve already tested the project from the main branch, your next step is to build and test your code locally, following the same procedures. Remember that if your project has dependencies on other GitHub projects, you’ll need to fork those as well, as references are relative. In my case, I had to fork seastar, scylla-ami, and scylla-swagger-ui.

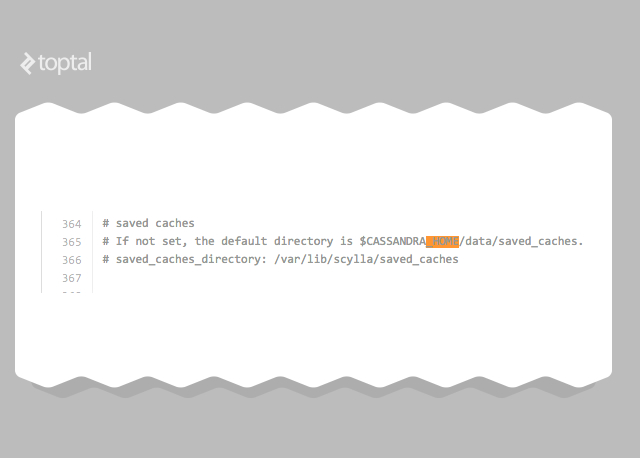

The bug I tackled was relatively simple. The documentation in conf/scylla.yaml referred to three configurable directories: one for data files, one for commit logs, and one seemingly unused directory for caches. All defaulted to subdirectories of $CASSANDRA_HOME:

Examining the code, I discovered discrepancies in the defaults. As highlighted in issue #372 (my starting point), $CASSANDRA_HOME shouldn’t be used. I confirmed this by experimenting with different configurations, removing the setting from the configuration file, and verifying the directories used. Once confident in my findings, I added, committed, and pushed the modified file:

| |

Notice that I included the issue number, preceded by a hash symbol (#), in the commit message. This instructs GitHub to automatically link my code changes to the relevant issue.

It’s important to note that during my code review, I noticed that the third directory, intended for caches, wasn’t being used. It was tempting to go a step further and remove this setting or add a comment indicating its unused status. However, that would have fallen outside the scope of issue #372, and it’s crucial to keep changes focused and relevant to the task at hand.

At this point, the bug is fixed within my private fork on GitHub. Now comes the part that used to make me apprehensive: formally requesting the ScyllaDB team to incorporate my code—in other words, creating a pull request.

The Final Step: The Pull Request

I find creating pull requests through GitHub’s web interface more intuitive and less error-prone than using the command line. To create my pull request, all I needed to do was click the small green button next to my branch name:

Note that GitHub automatically generated the comment. While my branch had one new commit, 14 additional commits had been added to the main repository since I created my fork. So, I clicked the green icon on the left.

Fortunately, my commit didn’t conflict with the 14 new commits, and GitHub gave me the green light to proceed. The commit message, though brief, provided all the necessary information: the purpose of my code change and its relation to the issue. As I clicked the button to confirm my request, I reflected on the fear I had felt just days earlier. It now felt unfounded. In the unlikely event that my fix was incorrect, it simply wouldn’t be accepted, and that would be the end of it.

If you check the issue details now, you’ll notice that GitHub automatically added a note indicating that a pull request exists for this issue. This is the beauty of including “#372” in the commit message—it prevents others from needlessly spending time on an already resolved issue.

Final Thoughts

With my pull request submitted, I awaited notification of its acceptance, knowing it could take a few days or even weeks. Someone would need to review my code, verify its functionality, ensure it effectively addresses the problem, and most importantly, confirm that it doesn’t introduce new bugs elsewhere in the codebase. This process takes time, and patience is key. In the end, if accepted, ScyllaDB gains a new contributor and resolves an issue, and I have my first OSS contribution.

Now, it’s your turn to give it a try. You might just discover that it’s not as intimidating as it seems.