Chris Jones, Researcher for Statewatch

This article delves into the numerous legal obstacles faced by the EU’s Data Retention Directive, both at national and EU levels. This is the third installment in a series examining this controversial legislation, which has recently been overturned by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). The information presented is a result of research conducted by Statewatch as part of the SECILE project, which focuses on the impact, legitimacy, and effectiveness of counter-terrorism measures in securing Europe.

Initial Legal Challenge within the EU Court of Justice

The Data Retention Directive faced its first legal challenge when Ireland, with Slovakia’s support, requested the EU Court of Justice to invalidate the Directive due to an incorrect legal basis. They argued that data retention fell under the purview of “police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters” within the EU Treaty, not the internal market. However, the ECJ dismissed the case in February 2009, asserting that Directive 2006/24 governs operations separate from police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters. The court stated that the directive doesn’t standardize law enforcement agencies’ access to data, nor does it regulate how this data is used or exchanged between these authorities. It concluded that Directive 2006/24 primarily targets the operations of service providers within the internal market, excluding state activities outlined in Title VI of the EU Treaty.

Challenges within Bulgaria

In Bulgaria, the NGO Access to Information Program initiated legal action that resulted in the first ruling on national laws implementing the Directive. In December 2008, Bulgaria’s Supreme Administrative Court nullified a section of the implementing legislation. This section granted the Ministry of Interior “passive access via computer terminal” to retained data and permitted access to “security services and other law enforcement bodies” without a warrant. The court determined that this provision lacked limitations on data access through computer terminals and did not offer adequate safeguards for the right to privacy as outlined in Article 32, Paragraph 1 of the Bulgarian Constitution. It also found the legislation deficient in establishing a system to protect against unwarranted intrusions into personal or familial matters and safeguards for honor, dignity, and reputation. Furthermore, the court pointed out that the legislation failed to acknowledge other pertinent laws like the Penal Procedure Code, the Special Surveillance Means Act, and the Personal Data Protection Act, all of which define the conditions for granting access to personal data.

Challenges within Hungary

In June 2008, the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (HCLU or TASZ, Társaság a Szabadságjogkért) requested that the Hungarian Constitutional Court review Act C of 2003 on electronic communications, specifically its amendment concerning data retention. They sought an “ex-post examination” of the amendment, alleging its unconstitutionality and demanding the annulment of data retention provisions. The HCLU argued that Act C already contained numerous restrictive data retention provisions before the amendment. The changes introduced only added the retention of Internet communications data and removed the loosely defined but pre-existing legal justifications for data processing. The HCLU contended that these amendments disregarded the Directive’s provisions, which state that data should be “accessible for the investigation, detection, and prosecution of serious crimes.” Although filed in 2008, the case is still pending. Fanny Hidvégi of the HCLU attributes the delay to new restrictions on submitting cases to the Constitutional Court, implemented on January 1, 2012. These restrictions led to the automatic dismissal of all pending cases from individuals or institutions no longer authorized to submit them. The HCLU has now initiated a new, extensive process that necessitates exhausting all other legal avenues before the Constitutional Court can review Hungary’s data retention measures.

Challenges within Romania

In October 2009, the Romanian Constitutional Court determined that the proposed national legislation to enact the Data Retention Directive violated Romanian constitutional rights. This included provisions protecting freedom of movement, the right to a private and family life, the confidentiality of correspondence, and freedom of expression. The court deemed the government’s attempt to justify mandatory telecommunications data retention by citing unspecified “threats to national security” as unlawful. Furthermore, the court referenced the 1978 ECHR ruling in Klass v Germany, which established that employing surveillance measures without adequate and sufficient safeguards could lead to the erosion of democracy under the guise of protecting it.

In October 2011, the European Commission urged the Romanian government to introduce new laws transposing the Directive, issuing a “reasoned opinion” under Article 258 of the TFEU. This action carried the threat of a full infringement procedure at the European Court of Justice if ignored. Consequently, a new law was drafted but met with rejection from the Romanian Senate. The proposed law faced heavy criticism from the media leading up to the vote. The country’s Data Protection Authority withheld its endorsement, stating that articles pertaining to security services remained ambiguous. Civil society groups also voiced opposition. Even the government refrained from sponsoring the law, leaving it to the Minister of Communications and Information Society to propose it in his capacity as an MP rather than a minister. Strong backing from the Minister of European Affairs fueled criticism, suggesting that the push for the law stemmed solely from avoiding sanctions by the European Court of Justice.

In the end, the Senate vote proved inconclusive, and the legislation proceeded to the Chamber of Deputies. At the end of May 2012, it was approved with 197 votes in favor, 18 against, and a significant number of abstentions among the 332 deputies. Concerns about fundamental rights were largely absent from discussions within the Chamber of Deputies and the two primary committees responsible for debating the law. Critics contend that provisions related to accessing retained data are even more problematic in the final version compared to the initial proposal. On February 21, 2013, the European Commission withdrew the infringement procedure it had launched in 2011.

Challenges within Cyprus

In February 2011, the Supreme Court of Cyprus ruled that certain aspects of the national law transposing the Data Retention Directive were in violation of the Cypriot constitution and established case law on surveillance. This case stemmed from individuals whose telecommunications data was disclosed to the police based on District Court orders. The individuals argued that the laws underpinning these orders, namely Articles 4 and 5 of Law 183(I) 2007, which aimed to harmonize Cypriot law with the Directive, and consequently the District Court orders themselves infringed upon their rights to privacy and confidentiality of communications. The Supreme Court concurred that the petitioners’ rights had indeed been violated, leading to the annulment of provisions deemed to exceed the requirements outlined in the Data Retention Directive. However, the court refrained from questioning the legality of the Directive itself.

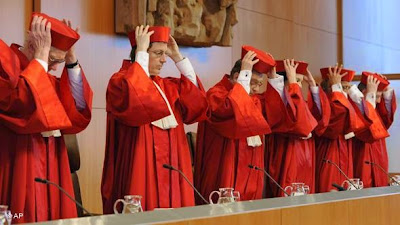

Challenges within Germany

The Bundestag passed legislation integrating the Data Retention Directive into the Telecommunication Act and Code of Criminal Procedure on November 9, 2007, which came into effect on January 1, 2008. One day prior, on December 31, 2007, 35,000 German citizens, represented by the NGO AK Vorrat, submitted a complaint regarding the legislation to the Federal Constitutional Court. On March 2, 2010, the court determined that the transposing provisions constituted a disproportionate infringement on Article 10 (confidentiality of communications) of the Basic Law (Grundgesetz) and violated legal standards related to purpose limitation, data security, transparency, and legal remedies.

It’s important to note that the court did not rule on the Directive itself, stating that data retention is, in principle, a proportionate response to investigating serious crimes and preventing imminent threats against life, bodily harm, personal freedom, and the safety and security of the Federal Republic or its individual states. The court’s stance was that the newly enacted domestic law failed to meet legal standards concerning purpose limitation (restrictions on the use of retained data), data security, transparency, and the availability of legal remedies.

In January 2011, the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) proposed a “quick freeze” system for limited data preservation during criminal investigations as an alternative to data retention. Under this system, police and/or public prosecutors would issue “quick freeze” orders to access metadata already held by telecommunication providers, such as billing information. Accessing this “frozen” data would require judicial approval. Additionally, the MoJ proposed an obligation for ISPs to retain internet traffic data for seven days. This would allow investigators to identify individuals behind known IP addresses, particularly in cases involving child pornography. Criminal investigators would request traffic and communication data through service providers without having direct access. This paper reflected proposals from the Federal Commissioner for Data Protection in June 2010, along with suggestions from privacy advocates.

More radical activists argued that any mandatory storage of communications data should be outlawed. Conversely, the Interior Ministry rejected these proposals, insisting on fully implementing the Directive. They argued that the Constitutional Court had already established that it was possible to implement the Directive while safeguarding individual privacy through robust data security measures. These included encryption and the “four eyes principle” (requiring approval from at least two individuals) as prerequisites for accessing data and log files, strict purpose limitation, and the protection of professions bound by confidentiality.

The MoJ drafted a “quick freeze” bill in April 2012, but it was never introduced in Parliament due to sustained opposition from the Interior Ministry, who were dissatisfied with the proposed freezing periods. They demanded three months instead of the one month suggested by the Ministry of Justice and sought to include offenses such as fraud and hacking. The debate continues, and new legislation has yet to be introduced.

Meanwhile, the European Commission initiated infringement proceedings and escalated the case to the European Court of Justice in July 2012, seeking to impose a daily fine of €315,000.

Challenges within the Czech Republic

On March 13, 2011, the Czech Republic’s Constitutional Court declared that the national law implementing the Directive was unconstitutional. They determined that the retention period exceeded the Directive’s requirements and that the data’s use was not restricted to instances of serious crime or terrorism. The court found the national legislation lacking clear and comprehensive rules for protecting personal data and informing individuals whose data had been requested. Echoing Germany’s stance, the court maintained that it could not review the Directive itself but noted that, in principle, nothing prevented its implementation in a manner consistent with constitutional law.

A subsequent Constitutional Court decision in December 2011 scrutinized the procedures for obtaining access to retained data, deeming them overly vague and in breach of the proportionality rule. The court considered this a violation of the right to privacy and informational self-determination. In the interim, the Czech government amended the implementing legislation to address the court’s judgment. However, the NGO Iuridicum Remedium has filed new legal challenges against the revised legislation, arguing that the regulations remain inadequate and could potentially enable the “monitoring of content in Internet communications.”

Challenges within Slovakia

In August 2012, a group of Slovakian MPs, with support from the European Information Society Institute, filed a legal complaint against the legislation enacting the Data Retention Directive. They requested that the Slovak Constitutional Court examine whether the laws implementing the Directive and governing access to retained data by authorities align with constitutional provisions on proportionality, the rights to privacy and data protection, and freedom of speech. The complaint argues that these measures infringe upon provisions safeguarding privacy, data protection, and freedom of expression as outlined in Slovakian human rights law, the European Convention on Human Rights, and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. This complaint is still pending resolution.

Challenges within Sweden

The European Commission has been engaged in a protracted effort to align Sweden’s domestic legislation with the Data Retention Directive. Following Sweden’s failure to meet the initial September 2007 deadline, the Commission initiated infringement proceedings. In February 2010, the European Court of Justice ruled that Sweden had failed to fulfill its obligations. A legislative proposal was put forth in December 2010 and adopted in March 2012. The new law, intended to take effect in May 2012, was overwhelmingly approved by the Swedish parliament, with 233 MPs voting in favor, 41 against, and 19 abstaining. However, the Left Party and the Greens invoked a constitutional provision allowing one-sixth of parliament members to delay the enactment of new measures.

In May 2013, the European Court of Justice ordered Sweden to pay a €3 million fine for its delay in implementing the legislation. The court dismissed Sweden’s arguments regarding domestic controversy surrounding the law’s implementation, asserting that a Member State cannot justify non-compliance with European Union law based on its internal legal order, provisions, practices, or prevailing situations. They emphasized that this principle also applies to decisions like the Swedish Parliament’s choice to postpone the adoption of the bill designed to transpose the directive.

Challenges within the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU)

The most significant obstacle to the Data Retention Directive’s implementation emerged from joint cases brought by the NGO Digital Rights and plaintiffs in a case referred by the Austrian Constitutional Court. Following a hearing in July, the Advocate General’s opinion on the case, published in December 2013, recommended that the court declare the entire Directive incompatible with Articles 52(1) and 7 of the EU Charter. Article 52(1) states that limitations on rights must be legally established and must respect the essence of those rights and freedoms, while Article 7 pertains to the right to privacy. The case centers around the Directive’s compatibility with Articles 7 (respect for private and family life) and 8 (protection of personal data) of the European Union’s Charter of Fundamental Rights. During the hearing, representatives for those who brought the cases argued that the Directive fundamentally clashes with the Charter and that there is still no evidence to support its necessity or proportionality.

Representing the Austrian privacy group AK Vorrat, Edward Scheucher contended that the combined impact of restrictions on fundamental rights must be considered when assessing a measure’s legitimacy. He argued that, considering the revelations about PRISM, this cumulative effect significantly alters the outcome compared to when the German Constitutional Court decided to annul certain aspects of German transposition legislation. Furthermore, he stated that Austria’s implementation of the directive clearly demonstrates that a Charter-compliant national implementation of the Data Retention Directive is not feasible. This argument is strengthened by the fact that one of the primary authors of the Austrian implementation is among the 11,139 Austrian plaintiffs who challenged data retention before the Austrian Constitutional Court.

Responding to requests for evidence to support the Directive’s necessity, the Austrian and Irish governments presented new statistics on the use of retained data at the hearing. Representatives from Italy, Spain, and the UK, along with the Commission, the Council, and the Parliament, also argued in favor of the Directive. However, even the Directive’s proponents had to acknowledge a lack of statistical evidence. The UK admitted to having no “scientific data” to substantiate the need for data retention. Judge Thomas von Danwitz, the Court’s primary rapporteur for the hearing, requested information that led to the Directive’s adoption in 2006, given that the Commission claimed in 2008 to lack sufficient information for a comprehensive review. Meanwhile, legal representatives for the Council urged the Court not to strip law enforcement of their tools.

Finally, Advocate-General Cruz Villalón recommended that the Court address the cases by declaring that Directive 2006/24/EC is fundamentally incompatible with Article 52(1) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. He argued that this incompatibility stems from the limitations imposed on exercising fundamental rights due to the data retention obligation, which lack the necessary safeguards and principles for regulating data access and use. He also found Article 6 of Directive 2006/24 incompatible with Articles 7 and 52(1) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights, as it mandates Member States to retain data specified in Article 5 of the directive for up to two years.

The Grand Chamber’s judgment, analyzed in Steve Peers’ separate post, ultimately aligned with this recommendation. The EU has finally been compelled to revise its mandatory data retention regulations.

Barnard & Peers: chapter 9, chapter 25