There’s been a lot of interest in MPWTest ("The Simplest Testing Framework That Could Possibly Work"), my personal unit testing framework. Let’s dive into how it streamlines test-driven development (TDD) and makes it enjoyable.

I built MPWTest out of a desire to fully embrace TDD. This was before XCTest existed. Even SenTestKit, its predecessor, was relatively new, and I wasn’t aware of it.

MPWTest is unique. I find it surpasses xUnit-style frameworks (JUnit, SUnit, XCTest). While these frameworks are better than no testing, they can feel heavy, creating unnecessary hurdles that may contribute to developer resistance to unit testing.

Many see testing as a chore. It’s considered beneficial but tedious.

MPWTest changed that for me. It makes TDD enjoyable—more like a snack than a chore. These “snacks” are not only enjoyable but good for development, helping me maintain focus and productivity.

I wholeheartedly endorse MPWTest.

While I’m unfamiliar with standard practices, the fact that everything resides in a single file and is integrated into the build process makes it exceptionally fast.

It’s akin to Xcode previews but for testing, especially in the context of SwiftUI.

1/

— 𝔾𝕦𝕤𝕥𝕒𝕧𝕠 𝕄𝕦𝕔𝕙𝕠 𝕃𝕠𝕧𝕖 👌🏻 (@LongMuchoLove) May 28, 2020

The beauty of MPWTest is its ability to empower rapid and reliable code changes—the essence of agile:

Contrary to popular belief in Agile literature, agility hinges on the ability to modify code rapidly and securely. This relies on the ability to re-test code swiftly and effectively. Fast-running automated tests (“unit tests”) are the cornerstone of agility.

— Jason Gorman (only, more indoors than usual) (@jasongorman) April 18, 2020

Let me explain how it works.

Setup

Begin by compiling the testlogger binary from the MPWTest project. I place mine in /usr/local/bin. You can choose any location, adjusting the paths accordingly.

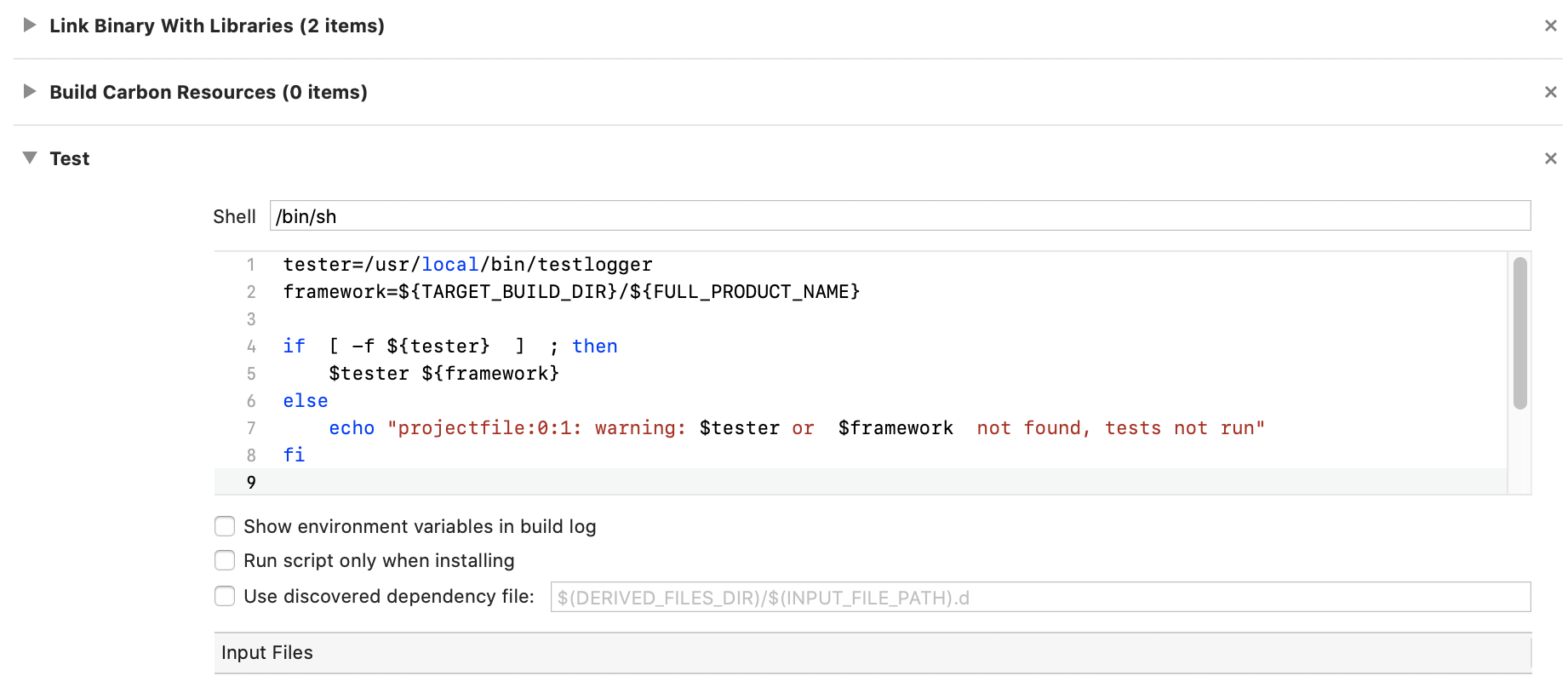

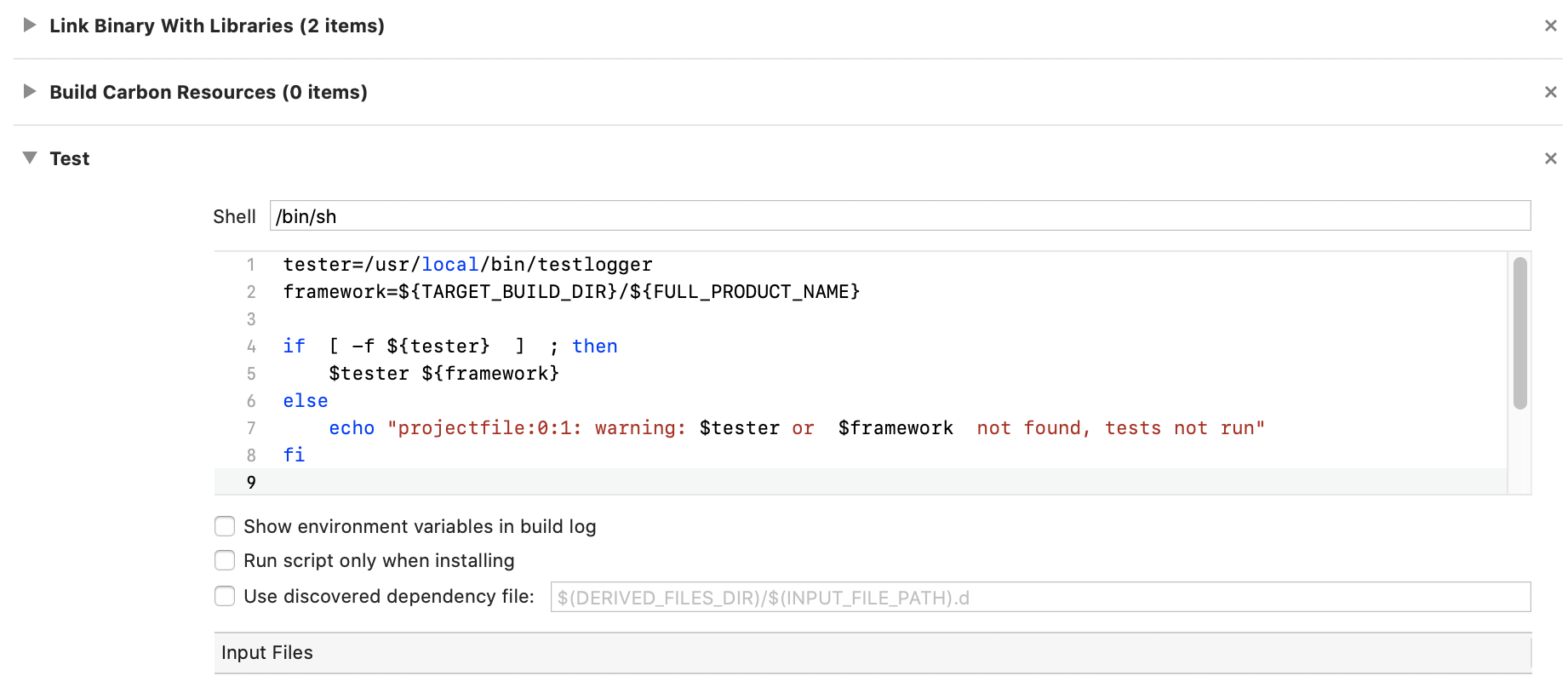

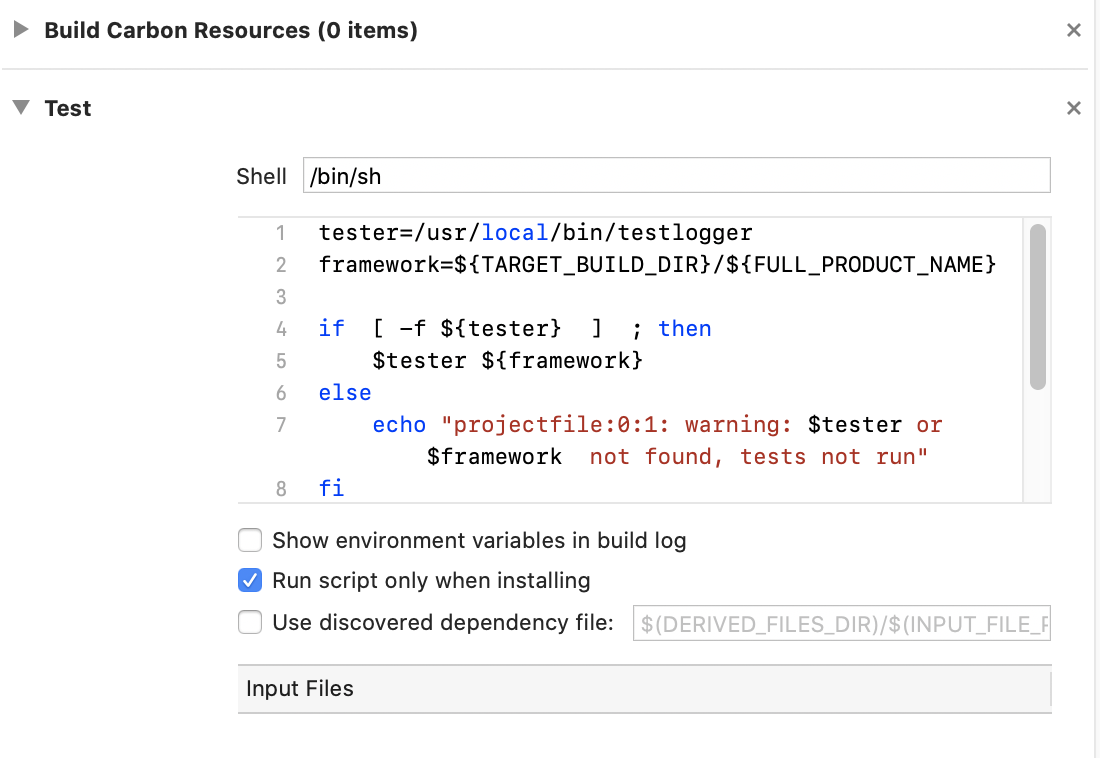

Next, add a “Script” build phase to your framework project (MPWTest is designed for frameworks).

` ``` tester=/usr/local/bin/testlogger framework=${TARGET_BUILD_DIR}/${FULL_PRODUCT_NAME}

if [ -f ${tester} ] ; then $tester ${framework} else echo “projectfile:0:1: warning: $tester or $framework not found, tests not run” fi

``` `

Your project’s Build Phases pane should look similar to this:

No separate test bundles or targets—simplified. This becomes particularly advantageous when dealing with multiple frameworks, eliminating unnecessary overhead.

Code

In the class you want to test, implement the +(NSArray*)testSelectors method, returning an array of test method names. For instance, here’s an example from a JSON parser:

` ``` +testSelectors { return @[ @“testParseJSONString”, @“testParseSimpleJSONDict”, @“testParseSimpleJSONArray”, @“testParseLiterals”, @“testParseNumbers”, @“testParseGlossaryToDict”, @“testDictAfterNumber”, @“testEmptyElements”, @“testStringEscapes”, @“testUnicodeEscapes”, @“testCommonStrings”, @“testSpaceBeforeColon”, ]; }

``` `

You could generate these names automatically, but I prefer an explicit list as part of the specification—it ensures no test is accidentally omitted.

Next, implement a test, for example, testUnicodeEscapes:

` ``` +(void)testUnicodeEscapes { MPWMASONParser *parser=[MPWMASONParser parser]; NSData *json=[self frameworkResource:@“unicodeescapes” category:@“json”]; NSArray *array=[parser parsedData:json]; NSString *first = [array objectAtIndex:0]; INTEXPECT([first length],1,@“length of parsed unicode escaped string”); INTEXPECT([first characterAtIndex:0], 0x1234, @“expected value”); IDEXPECT([array objectAtIndex:1], @"\n", @“second is newline”); }

``` `

The macros INTEXPECT() and IDEXPECT() assert integer and object equality, respectively. Others handle nil, boolean, and float comparisons.

I typically group tests in a testing category at the file’s end:

` ``` … @end

#import “DebugMacros.h”

@implementation MPWMASONParser(testing)

``` `

The DebugMacros.h header contains the EXPECT() macros and is the only dependency—no linking required.

Beyond a unified bundle, having tests within the class file simplifies navigation and comprehension. Tests serve as living documentation, always in context.

This approach avoids the complexities of parallel class hierarchies, a known source of friction and maintenance headaches.

Use

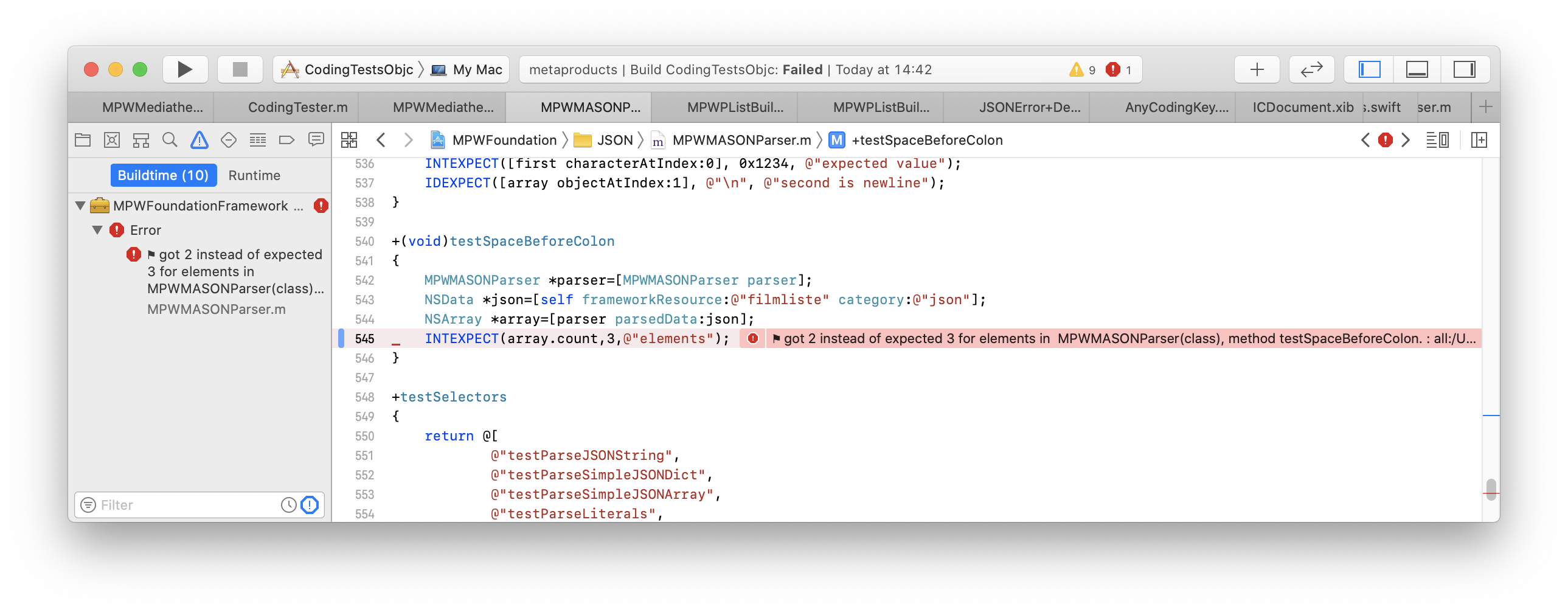

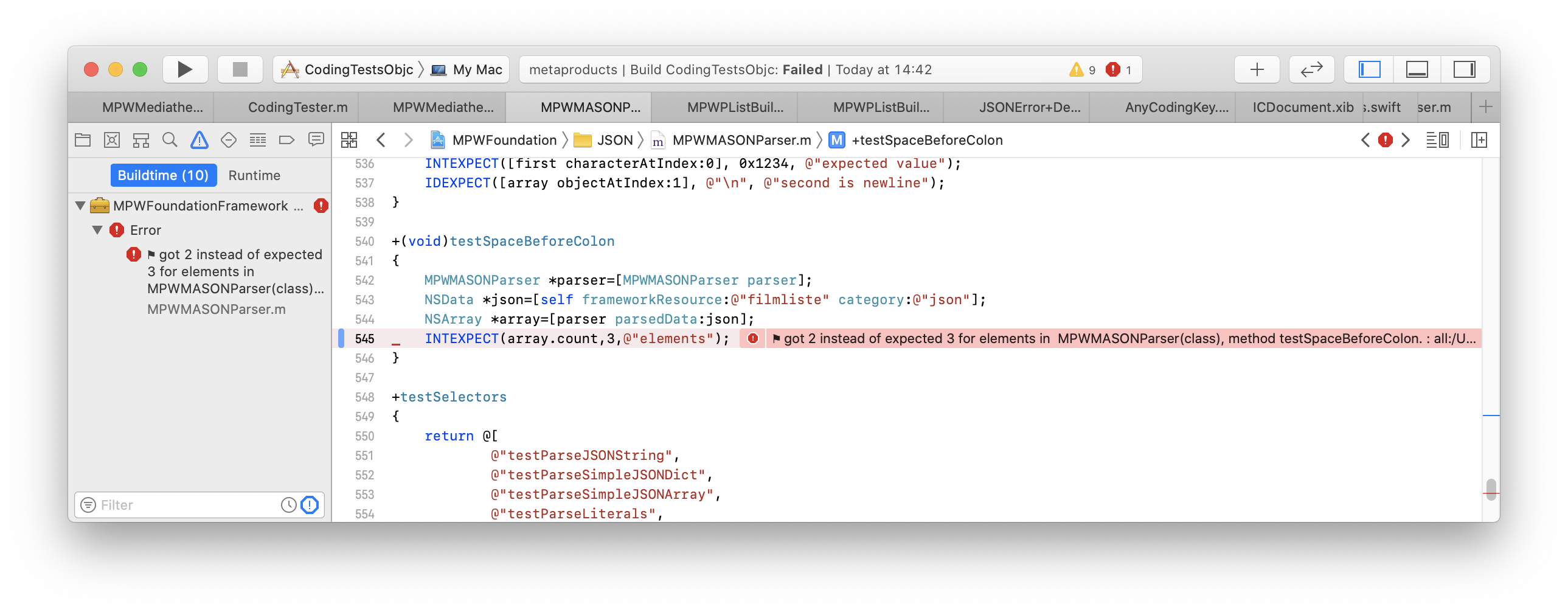

Once set up, build your projects—tests execute automatically. Test failures appear as expected:

My usual workflow:

- Add the test name to

+testSelectors. - Build (expecting tests to fail).

- While Xcode builds, add an empty test method.

- Build again (ensuring tests now pass).

- Add an

EXPECT()orEXPECTTRUE(false,@"impelemented")as a placeholder.

This iterative process may seem involved but keeps me in sync with the build system’s feedback.

Integrating tests into every build fosters confidence and promotes a proactive approach to code quality.

This constant feedback loop encourages maintaining green tests, as build failures directly impact development. It also motivates writing fast tests, making testing seamless.

Caveats

There are some downsides. Xcode’s unit test integration isn’t fully supported. This wasn’t a priority when MPWTest was conceived, as Apple’s focus was on their integrated solution.

However, displaying test failures as errors and navigation to the failing line works. This leverages Xcode’s mechanism for parsing compiler output from stdout.

While Xcode’s unit test UI has its merits, it can reinforce the separation between testing and development. With always-running, green, and fast tests, dedicated UI becomes less critical.

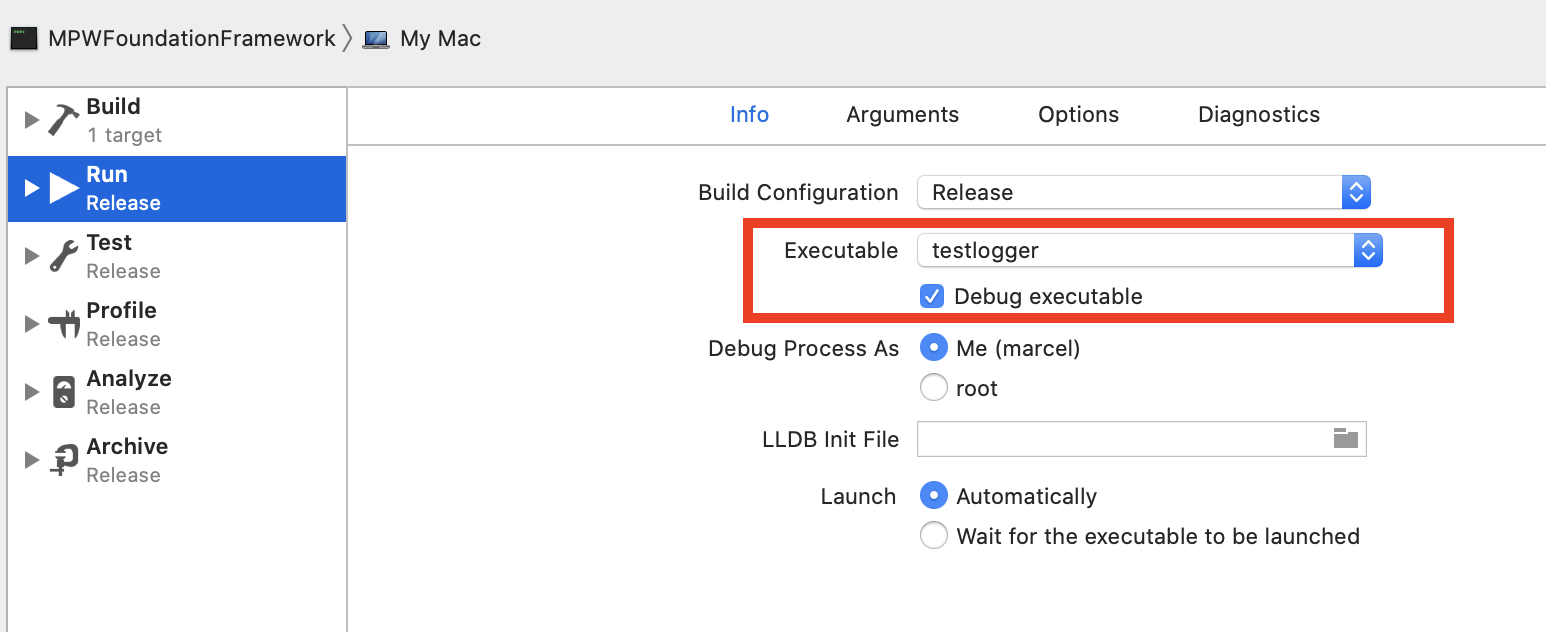

Debugging is another hurdle. A test failure halts the build, preventing executable debugging. As I primarily use TDD for failure detection, this is rarely an issue.

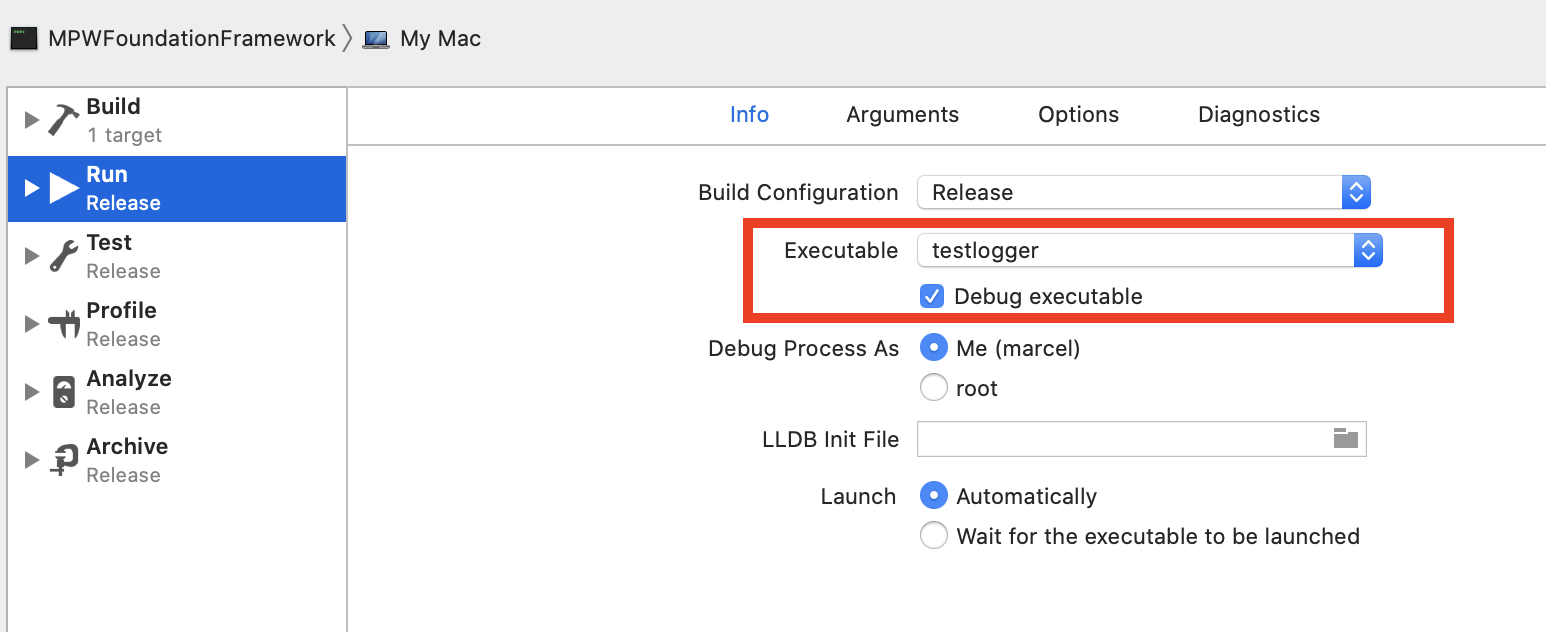

Previously, I resorted to command-line debugging (e.g., lldb testlogger MPWFoundation). However, I discovered that you can specify an executable in your target’s build scheme. Setting this to testlogger enables framework debugging.

The remaining challenge is Xcode’s inability to run the executable after a build failure and the lack of build phase debugging.

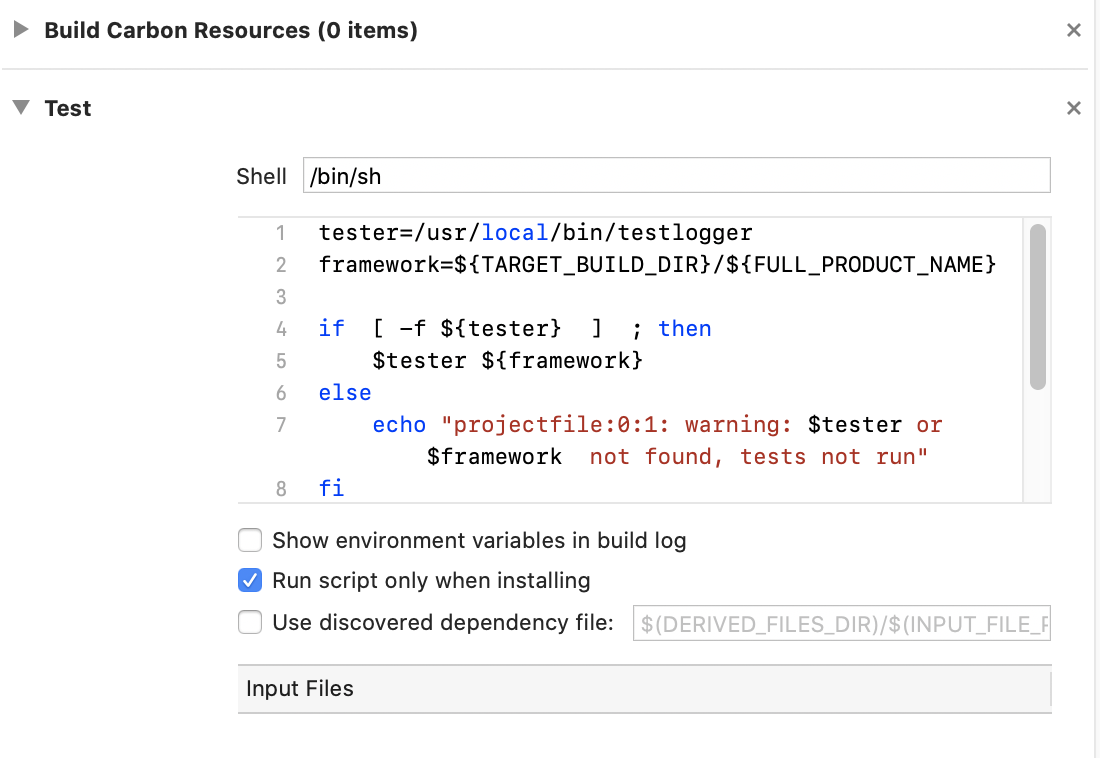

A workaround is temporarily disabling the Test build phase using the “Run script only when installing” flag.

While these are minor inconveniences, they stand out against the otherwise seamless experience.

You can still opt for dedicated test classes if needed. Additionally, every class can provide a test fixture object with setup and teardown methods, as in xUnit.

The runtime introspection used to discover tests is interesting and requires periodic updates to accommodate new system classes.

Outlook

I encourage you to explore MPWTest. Feedback, positive or negative, is invaluable.

Currently, there’s no Swift support. While Objective-C compatibility may exist, Swift’s dynamism might require compiler-level changes for similar integration. I’m actively researching Swift interoperability, and new possibilities are emerging.

These lessons will undoubtedly shape linguistically integrated testing in Objective-Smalltalk. As with many aspects of Objective-Smalltalk, the path to seamless integration is within reach.

This experience underscores the simplicity of unit testing. As Kent Beck once said, everyone should build their own. So, go forth and create amazing things!