This tutorial provides a concise explanation of monads and demonstrates their implementation in five popular programming languages: JavaScript, Python, Ruby, Swift, and Scala. Whether you’re seeking to understand monads in a specific language or compare different implementations, this guide has you covered!

By leveraging monads, you can effectively eliminate various bugs, including null-pointer exceptions, unhandled exceptions, and race conditions.

This tutorial covers the following:

- An overview of category theory

- The definition of a monad

- Implementations of Option (“Maybe”), Either, and Future monads, accompanied by a sample program illustrating their use in JavaScript, Python, Ruby, Swift, and Scala

Let’s embark on this journey! Our first destination is category theory, the foundation of monads.

Introduction to Category Theory

Category theory, a mathematical field that gained prominence in the mid-20th century, underpins many functional programming concepts, including monads. We’ll briefly examine some category theory concepts relevant to software development.

Three core concepts define a category:

- Type represents data types as seen in statically typed languages, such as

Int,String,Dog,Cat, etc. - Functions establish connections between types, visualized as arrows from one type to another (or to themselves). A function $f$ from type $T$ to type $U$ is denoted as $f: T \to U$, analogous to a programming function taking a $T$ type argument and returning a $U$ type value.

- Composition combines existing functions to create new ones, denoted by the $\cdot$ operator. In a category, for any functions $f: T \to U$ and $g: U \to V$, there exists a unique function $h: T \to V$ denoted as $f \cdot g$. Essentially, this operation maps a pair of functions to a new one. Programming languages readily support this operation. For example, given a function $strlen: String \to Int$ returning the length of a string and another function $even: Int \to Boolean$ checking for even numbers, we can create a function $even{\_}strlen: String \to Boolean$ to determine if a string’s length is even. Here, $even{\_}strlen = even \cdot strlen$. Composition implies:

- Associativity: $f \cdot g \cdot h = (f \cdot g) \cdot h = f \cdot (g \cdot h)$

- Identity function existence: $\forall T: \exists f: T \to T$. In simpler terms, for every type $T$, there’s a function mapping $T$ to itself.

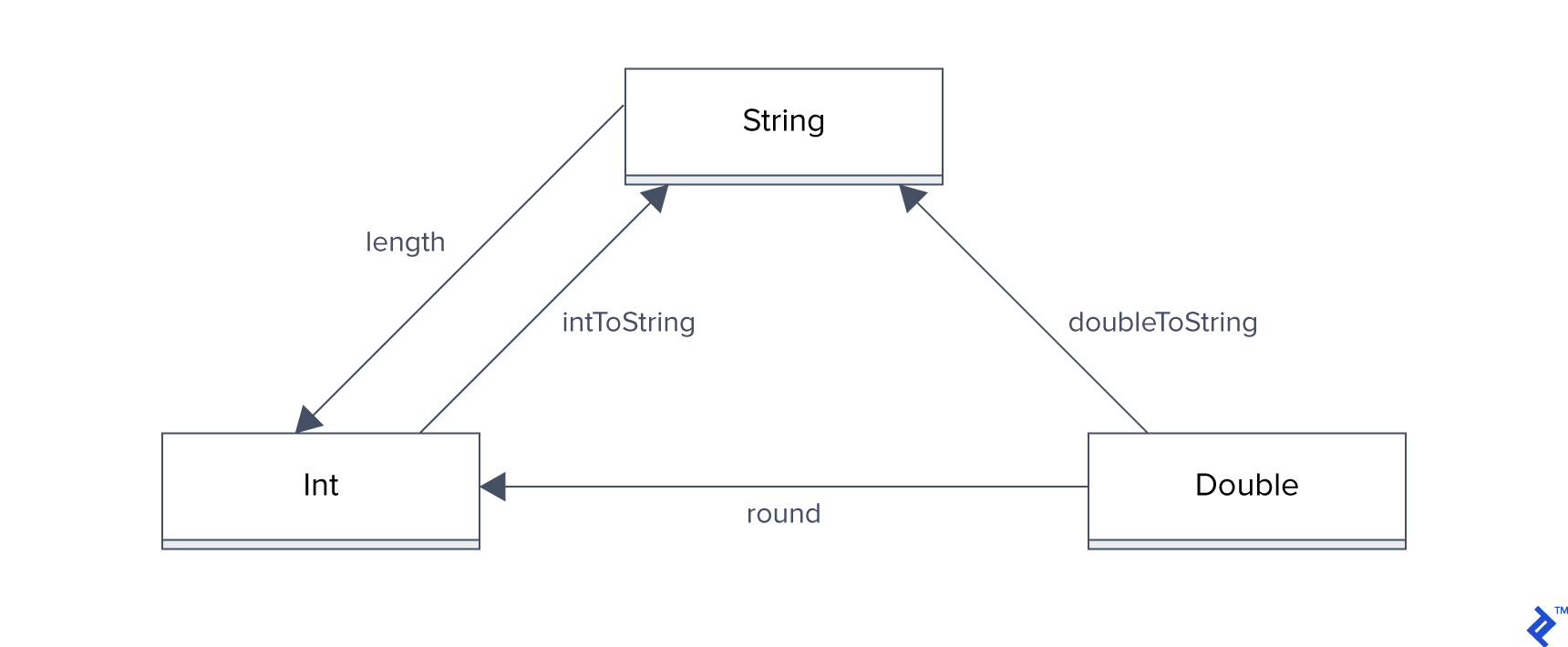

Let’s visualize a simple category:

Note: We assume Int, String, and other types here are non-nullable, meaning the null value is absent.

Note 2: This diagram represents only a portion of a category, sufficient for our discussion as it includes the essential elements without unnecessary complexity. A complete category would also include composed functions like $roundToString: Double \to String = intToString \cdot round$ to satisfy the composition requirement.

You’ll observe that functions within this category are quite basic. In fact, it’s nearly impossible to introduce bugs into them. There are no nulls, no exceptions—just arithmetic and memory operations. The only potential issues arise from processor or memory failures, requiring program termination—a rare occurrence.

Having all our code operate at this level of stability would be ideal! However, real-world applications require functionalities like I/O. This is where monads come to the rescue: They encapsulate unstable operations within small, well-tested code units, enabling stable calculations throughout your application!

Enter Monads

Let’s refer to unstable behavior like I/O as a side effect. Our goal is to work with previously defined functions like length and types like String in a stable manner, even with this side effect.

Starting with an empty category $M[A]$, we aim to create a category containing values with a specific side effect and values without any. Initially, this category is empty and not very useful. To enhance its utility, we’ll follow these steps:

- Populate it with values from category $A$ types like

String,Int,Double, etc. (green boxes in the diagram below). - With these values, meaningful operations are still limited. So, for each function $f: T \to U$ from $A$, we’ll create a function $g: M[T] \to M[U]$ (blue arrows in the diagram below). This enables us to perform the same operations on values in category $M[A]$ as in category $A$.

- This new category $M[A]$ introduces a new class of functions with the signature $h: T \to M[U]$ (red arrows in the diagram below), arising from promoting values in step one. These functions distinguish working with $M[A]$ from working with $A$. The final step ensures these functions operate seamlessly on types in $M[A]$, allowing us to derive function $m: M[T] \to M[U]$ from $h: T \to M[U]$.

![Creating a new category: Categories A and M[A], plus a red arrow from A's Double to M[A]'s Int, labelled "roundAsync". M[A] reuses every value and function of A at this point.](https://assets.toptal.io/images?url=https%3A%2F%2Fuploads.toptal.io%2Fblog%2Fimage%2F127403%2Ftoptal-blog-image-1540211900150-82f554ff98243b2ef4c9f00c13f64c14.png)

We define two methods to promote values of $A$ types to $M[A]$ types: one without side effects and one with.

- The first, called $pure$, applies to each value of a stable category: $pure: T \to M[T]$. The resulting $M[T]$ values have no side effects, hence the name $pure$. For instance, in an I/O monad, $pure$ immediately returns a value without the possibility of failure.

- The second, called $constructor$, unlike $pure$, returns $M[T]$ with potential side effects. For example, an async I/O monad’s $constructor$ could fetch data from the web, returning it as a

String. The returned value would have the type $M[String]$ in this case.

With these two promotion methods, you, the programmer, decide which function to use based on the program’s requirements. Consider fetching the HTML page from https://www.toptal.com/javascript/option-maybe-either-future-monads-js. You create a function $fetch$. Due to potential issues like network failures, the return type is $M[String]$. The function signature becomes $fetch: String \to M[String]$, using the $constructor$ for $M$ within its body.

For testing, you create a mock function $fetchMock: String \to M[String]$. While the signature remains the same, $fetchMock$ directly injects the HTML page without any unstable network operations, using $pure$ in its implementation.

Next, we need a function to safely promote any function $f$ from category $A$ to $M[A]$ (blue arrows in the diagram). This function is $map: (T \to U) \to (M[T] \to M[U])$.

We now have a category that can handle side effects (using $constructor$) and includes all functions from the stable category, ensuring their stability within $M[A]$. This introduces functions like $f: T \to M[U]$, such as $pure$, $constructor$, and combinations of these with $map$. We need a way to work with arbitrary functions in the form $f: T \to M[U]$.

To apply a function based on $f$ to $M[T]$, using $map$ would result in a function $g: M[T] \to M[M[U]]$, introducing an undesired additional category $M[M[A]]$. To address this, we introduce the $flatMap: (T \to M[U]) \to (M[T] \to M[U])$ function.

Let’s illustrate the need for $flatMap$. Assume we’ve completed step 2, having $pure$, $constructor$, and $map$. We want to fetch an HTML page from toptal.com, scan all URLs within it, and fetch those as well. We create a function $fetch: String \to M[String]$ to fetch a single URL and return its HTML page.

Applying this function to a URL gives us $x: M[String]$, the toptal.com page. After some transformations on $x$, we obtain a URL $u: M[String]$. We’d like to apply $fetch$ to $u$, but its input type is $String$, not $M[String]$. This is where $flatMap$ comes in, converting $fetch: String \to M[String]$ to $m_fetch: M[String] \to M[String]$.

Having completed all three steps, we can now compose any value transformations we need. For example, given a value $x$ of type $M[T]$ and a function $f: T \to U$, we can apply $f$ to $x$ using $map$, resulting in a value $y$ of type $M[U]$. This ensures 100% bug-free value transformations as long as $pure$, $constructor$, $map$, and $flatMap$ are implemented correctly.

Instead of handling potential issues related to side effects throughout your codebase, you only need to ensure the correct implementation of these four functions. At the end of your program, you’ll have a single $M[X]$ from which you can safely extract the value $X$ and handle any error cases.

This is essentially what a monad is: an entity implementing $pure$, $map$, and $flatMap$. (While $map$ can be derived from $pure$ and $flatMap$, its widespread use and utility warrant its inclusion in the definition.)

The Option Monad, a.k.a. the Maybe Monad

Let’s delve into the practical implementation and use of monads. Our first example, the Option monad, addresses the infamous null pointer error common in classic programming languages. Tony Hoare, the inventor of null, famously called it his “Billion Dollar Mistake”:

This has led to innumerable errors, vulnerabilities, and system crashes, which have probably caused a billion dollars of pain and damage in the last forty years.

Let’s see how we can improve upon this. The Option monad either holds a non-null value or no value at all. This resembles a null value, but with the Option monad, we can safely utilize our well-defined functions without the risk of encountering null pointer exceptions. Let’s examine implementations in various languages:

JavaScript—Option Monad/Maybe Monad

class Monad {

// pure :: a -> M a

pure = () => { throw "pure method needs to be implemented" }

// flatMap :: # M a -> (a -> M b) -> M b

flatMap = (x) => { throw "flatMap method needs to be implemented" }

// map :: # M a -> (a -> b) -> M b

map = f => this.flatMap(x => new this.pure(f(x)))

}

export class Option extends Monad {

// pure :: a -> Option a

pure = (value) => {

if ((value === null) || (value === undefined)) {

return none;

}

return new Some(value)

}

// flatMap :: # Option a -> (a -> Option b) -> Option b

flatMap = f =>

this.constructor.name === 'None' ?

none :

f(this.value)

// equals :: # M a -> M a -> boolean

equals = (x) => this.toString() === x.toString()

}

class None extends Option {

toString() {

return 'None';

}

}

// Cached None class value

export const none = new None()

Option.pure = none.pure

export class Some extends Option {

constructor(value) {

super();

this.value = value;

}

toString() {

return `Some(${this.value})`

}

}

Python—Option Monad/Maybe Monad

class Monad:

# pure :: a -> M a

@staticmethod

def pure(x):

raise Exception("pure method needs to be implemented")

# flat_map :: # M a -> (a -> M b) -> M b

def flat_map(self, f):

raise Exception("flat_map method needs to be implemented")

# map :: # M a -> (a -> b) -> M b

def map(self, f):

return self.flat_map(lambda x: self.pure(f(x)))

class Option(Monad):

# pure :: a -> Option a

@staticmethod

def pure(x):

return Some(x)

# flat_map :: # Option a -> (a -> Option b) -> Option b

def flat_map(self, f):

if self.defined:

return f(self.value)

else:

return nil

class Some(Option):

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

self.defined = True

class Nil(Option):

def __init__(self):

self.value = None

self.defined = False

nil = Nil()

Ruby—Option Monad/Maybe Monad

class Monad

# pure :: a -> M a

def self.pure(x)

raise StandardError("pure method needs to be implemented")

end

# pure :: a -> M a

def pure(x)

self.class.pure(x)

end

def flat_map(f)

raise StandardError("flat_map method needs to be implemented")

end

# map :: # M a -> (a -> b) -> M b

def map(f)

flat_map(-> (x) { pure(f.call(x)) })

end

end

class Option < Monad

attr_accessor :defined, :value

# pure :: a -> Option a

def self.pure(x)

Some.new(x)

end

# pure :: a -> Option a

def pure(x)

Some.new(x)

end

# flat_map :: # Option a -> (a -> Option b) -> Option b

def flat_map(f)

if defined

f.call(value)

else

$none

end

end

end

class Some < Option

def initialize(value)

@value = value

@defined = true

end

end

class None < Option

def initialize()

@defined = false

end

end

$none = None.new()

Swift—Option Monad/Maybe Monad

import Foundation

enum Maybe<A> {

case None

case Some(A)

static func pure<B>(_ value: B) -> Maybe<B> {

return .Some(value)

}

func flatMap<B>(_ f: (A) -> Maybe<B>) -> Maybe<B> {

switch self {

case .None:

return .None

case .Some(let value):

return f(value)

}

}

func map<B>(f: (A) -> B) -> Maybe<B> {

return self.flatMap { type(of: self).pure(f($0)) }

}

}

Scala—Option Monad/Maybe Monad

import language.higherKinds

trait Monad[M[_]] {

def pure[A](a: A): M[A]

def flatMap[A, B](ma: M[A])(f: A => M[B]): M[B]

def map[A, B](ma: M[A])(f: A => B): M[B] =

flatMap(ma)(x => pure(f(x)))

}

object Monad {

def apply[F[_]](implicit M: Monad[F]): Monad[F] = M

implicit val myOptionMonad = new Monad[MyOption] {

def pure[A](a: A) = MySome(a)

def flatMap[A, B](ma: MyOption[A])(f: A => MyOption[B]): MyOption[B] = ma match {

case MyNone => MyNone

case MySome(a) => f(a)

}

}

}

sealed trait MyOption[+A] {

def flatMap[B](f: A => MyOption[B]): MyOption[B] =

Monad[MyOption].flatMap(this)(f)

def map[B](f: A => B): MyOption[B] =

Monad[MyOption].map(this)(f)

}

case object MyNone extends MyOption[Nothing]

case class MySome[A](x: A) extends MyOption[A]

We start by implementing a base Monad class for all our monad implementations. This simplifies things significantly, as implementing just pure and flatMap for a specific monad provides access to many other methods automatically (limited to map in our examples for brevity, but generally including useful methods like sequence and traverse for handling arrays of Monads).

We express map as a composition of pure and flatMap. Examining flatMap’s signature, $flatMap: (T \to M[U]) \to (M[T] \to M[U])$, reveals its similarity to $map: (T \to U) \to (M[T] \to M[U])$. The only difference is the additional $M$ in the middle, which we address using pure to convert $U$ into $M[U]$. This way, we express map in terms of flatMap and pure.

This approach works seamlessly in Scala due to its advanced type system and in dynamically typed languages like JS, Python, and Ruby. However, Swift, being statically typed and lacking advanced type features like higher-kinded types, requires a separate map implementation for each monad.

Note that the Option monad is already a standard feature in languages like Swift and Scala, explaining the slight name variations in our implementations.

With our base Monad class in place, let’s move on to the Option monad implementations. As mentioned earlier, the core concept is that Option either holds a value (Some) or not (None).

The pure method simply promotes a value to Some, while flatMap checks the Option’s current state. If it’s None, it returns None. If it’s Some with an underlying value, it extracts this value, applies f() to it, and returns the result.

Using just these two functions and map, encountering a null pointer exception becomes impossible. (A potential issue could arise within our flatMap implementation, but that’s just a few lines of code checked once. Afterward, we can confidently use our Option monad implementation throughout our codebase without fearing null pointer exceptions.)

The Either Monad

Next up is the Either monad, essentially an Option monad with Some renamed to Right and None renamed to Left. However, Left in this case can also hold a value.

This is useful for representing exceptions. If an exception occurs, the Either value will be Left(Exception). The flatMap function halts progression if the value is Left, mimicking exception throwing behavior: If an exception happens, further execution stops.

JavaScript—Either Monad

import Monad from './monad';

export class Either extends Monad {

// pure :: a -> Either a

pure = (value) => {

return new Right(value)

}

// flatMap :: # Either a -> (a -> Either b) -> Either b

flatMap = f =>

this.isLeft() ?

this :

f(this.value)

isLeft = () => this.constructor.name === 'Left'

}

export class Left extends Either {

constructor(value) {

super();

this.value = value;

}

toString() {

return `Left(${this.value})`

}

}

export class Right extends Either {

constructor(value) {

super();

this.value = value;

}

toString() {

return `Right(${this.value})`

}

}

// attempt :: (() -> a) -> M a

Either.attempt = f => {

try {

return new Right(f())

} catch(e) {

return new Left(e)

}

}

Either.pure = (new Left(null)).pure

Python—Either Monad

from monad import Monad

class Either(Monad):

# pure :: a -> Either a

@staticmethod

def pure(value):

return Right(value)

# flat_map :: # Either a -> (a -> Either b) -> Either b

def flat_map(self, f):

if self.is_left:

return self

else:

return f(self.value)

class Left(Either):

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

self.is_left = True

class Right(Either):

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

self.is_left = False

Ruby—Either Monad

require_relative './monad'

class Either < Monad

attr_accessor :is_left, :value

# pure :: a -> Either a

def self.pure(value)

Right.new(value)

end

# pure :: a -> Either a

def pure(value)

self.class.pure(value)

end

# flat_map :: # Either a -> (a -> Either b) -> Either b

def flat_map(f)

if is_left

self

else

f.call(value)

end

end

end

class Left < Either

def initialize(value)

@value = value

@is_left = true

end

end

class Right < Either

def initialize(value)

@value = value

@is_left = false

end

end

Swift—Either Monad

import Foundation

enum Either<A, B> {

case Left(A)

case Right(B)

static func pure<C>(_ value: C) -> Either<A, C> {

return Either<A, C>.Right(value)

}

func flatMap<D>(_ f: (B) -> Either<A, D>) -> Either<A, D> {

switch self {

case .Left(let x):

return Either<A, D>.Left(x)

case .Right(let x):

return f(x)

}

}

func map<C>(f: (B) -> C) -> Either<A, C> {

return self.flatMap { Either<A, C>.pure(f($0)) }

}

}

Scala—Either Monad

package monad

sealed trait MyEither[+E, +A] {

def flatMap[EE >: E, B](f: A => MyEither[EE, B]): MyEither[EE, B] =

Monad[MyEither[EE, ?]].flatMap(this)(f)

def map[EE >: E, B](f: A => B): MyEither[EE, B] =

Monad[MyEither[EE, ?]].map(this)(f)

}

case class MyLeft[E](e: E) extends MyEither[E, Nothing]

case class MyRight[A](a: A) extends MyEither[Nothing, A]

// ...

implicit def myEitherMonad[E] = new Monad[MyEither[E, ?]] {

def pure[A](a: A) = MyRight(a)

def flatMap[A, B](ma: MyEither[E, A])(f: A => MyEither[E, B]): MyEither[E, B] = ma match {

case MyLeft(a) => MyLeft(a)

case MyRight(b) => f(b)

}

}

Catching exceptions is also straightforward: simply map Left to Right. (We omit this in our examples for brevity.)

The Future Monad

Finally, let’s explore the Future monad. This monad acts as a container for a value available either immediately or in the near future. Using map and flatMap, you can create chains of Futures that wait for a Future value to resolve before executing the next dependent code block. This resembles the concept of Promises in JS.

Our objective is to bridge existing asynchronous APIs across different languages to a consistent base. Callbacks in $constructor$ offer the most straightforward design approach.

While callbacks introduced the “callback hell” problem in JavaScript and other languages, this won’t be an issue for us thanks to monads. In fact, the Promise object in JavaScript, designed to address callback hell, is a monad itself!

Let’s examine the Future monad’s constructor signature:

constructor :: ((Either err a -> void) -> void) -> Future (Either err a)

Breaking it down, we first define:

type Callback = Either err a -> void

Here, Callback is a function accepting either an error or a resolved value as an argument and returning nothing. Now the signature becomes:

constructor :: (Callback -> void) -> Future (Either err a)

We need to provide a function that returns nothing and triggers a callback once the asynchronous computation resolves to either an error or a value. This enables easy bridging for any language.

Turning to the Future monad’s internal structure, the key idea is a cache variable. This variable stores a value if the Future monad is resolved and remains empty otherwise. Subscribing to the Future with a callback triggers it immediately if the value is resolved. Otherwise, the callback is added to a subscribers list.

Upon Future resolution, each callback in the list is triggered exactly once with the resolved value in a separate thread (or as the next function in the event loop for JS). Careful synchronization primitive usage is crucial here to prevent race conditions.

The basic flow involves initiating the asynchronous computation provided as the constructor argument and pointing its callback to our internal callback method. Simultaneously, you can subscribe to the Future monad, adding your callbacks to the queue. Once the computation completes, the internal callback method invokes all queued callbacks. This approach closely resembles the asynchronous handling in Reactive Extensions (RxJS, RxSwift, etc.).

The Future monad’s public API consists of pure, map, and flatMap, similar to previous monads. Additionally, we include a couple of convenient methods:

-

asynctakes a synchronous blocking function and executes it in a separate thread. traversetakes an array of values and a function mapping a value to aFuture. It returns aFutureof an array containing resolved values.

Let’s see this in action:

JavaScript—Future Monad

import Monad from './monad';

import { Either, Left, Right } from './either';

import { none, Some } from './option';

export class Future extends Monad {

// constructor :: ((Either err a -> void) -> void) -> Future (Either err a)

constructor(f) {

super();

this.subscribers = [];

this.cache = none;

f(this.callback)

}

// callback :: Either err a -> void

callback = (value) => {

this.cache = new Some(value)

while (this.subscribers.length) {

const subscriber = this.subscribers.shift();

subscriber(value)

}

}

// subscribe :: (Either err a -> void) -> void

subscribe = (subscriber) =>

(this.cache === none ? this.subscribers.push(subscriber) : subscriber(this.cache.value))

toPromise = () => new Promise(

(resolve, reject) =>

this.subscribe(val => val.isLeft() ? reject(val.value) : resolve(val.value))

)

// pure :: a -> Future a

pure = Future.pure

// flatMap :: (a -> Future b) -> Future b

flatMap = f =>

new Future(

cb => this.subscribe(value => value.isLeft() ? cb(value) : f(value.value).subscribe(cb))

)

}

Future.async = (nodeFunction, ...args) => {

return new Future(cb =>

nodeFunction(...args, (err, data) => err ? cb(new Left(err)) : cb(new Right(data)))

);

}

Future.pure = value => new Future(cb => cb(Either.pure(value)))

// traverse :: [a] -> (a -> Future b) -> Future [b]

Future.traverse = list => f =>

list.reduce(

(acc, elem) => acc.flatMap(values => f(elem).map(value => [...values, value])),

Future.pure([])

)

Python—Future Monad

from monad import Monad

from option import nil, Some

from either import Either, Left, Right

from functools import reduce

import threading

class Future(Monad):

# __init__ :: ((Either err a -> void) -> void) -> Future (Either err a)

def __init__(self, f):

self.subscribers = []

self.cache = nil

self.semaphore = threading.BoundedSemaphore(1)

f(self.callback)

# pure :: a -> Future a

@staticmethod

def pure(value):

return Future(lambda cb: cb(Either.pure(value)))

def exec(f, cb):

try:

data = f()

cb(Right(data))

except Exception as err:

cb(Left(err))

def exec_on_thread(f, cb):

t = threading.Thread(target=Future.exec, args=[f, cb])

t.start()

def async(f):

return Future(lambda cb: Future.exec_on_thread(f, cb))

# flat_map :: (a -> Future b) -> Future b

def flat_map(self, f):

return Future(

lambda cb: self.subscribe(

lambda value: cb(value) if (value.is_left) else f(value.value).subscribe(cb)

)

)

# traverse :: [a] -> (a -> Future b) -> Future [b]

def traverse(arr):

return lambda f: reduce(

lambda acc, elem: acc.flat_map(

lambda values: f(elem).map(

lambda value: values + [value]

)

), arr, Future.pure([]))

# callback :: Either err a -> void

def callback(self, value):

self.semaphore.acquire()

self.cache = Some(value)

while (len(self.subscribers) > 0):

sub = self.subscribers.pop(0)

t = threading.Thread(target=sub, args=[value])

t.start()

self.semaphore.release()

# subscribe :: (Either err a -> void) -> void

def subscribe(self, subscriber):

self.semaphore.acquire()

if (self.cache.defined):

self.semaphore.release()

subscriber(self.cache.value)

else:

self.subscribers.append(subscriber)

self.semaphore.release()

Ruby—Future Monad

require_relative './monad'

require_relative './either'

require_relative './option'

class Future < Monad

attr_accessor :subscribers, :cache, :semaphore

# initialize :: ((Either err a -> void) -> void) -> Future (Either err a)

def initialize(f)

@subscribers = []

@cache = $none

@semaphore = Queue.new

@semaphore.push(nil)

f.call(method(:callback))

end

# pure :: a -> Future a

def self.pure(value)

Future.new(-> (cb) { cb.call(Either.pure(value)) })

end

def self.async(f, *args)

Future.new(-> (cb) {

Thread.new {

begin

cb.call(Right.new(f.call(*args)))

rescue => e

cb.call(Left.new(e))

end

}

})

end

# pure :: a -> Future a

def pure(value)

self.class.pure(value)

end

# flat_map :: (a -> Future b) -> Future b

def flat_map(f)

Future.new(-> (cb) {

subscribe(-> (value) {

if (value.is_left)

cb.call(value)

else

f.call(value.value).subscribe(cb)

end

})

})

end

# traverse :: [a] -> (a -> Future b) -> Future [b]

def self.traverse(arr, f)

arr.reduce(Future.pure([])) do |acc, elem|

acc.flat_map(-> (values) {

f.call(elem).map(-> (value) { values + [value] })

})

end

end

# callback :: Either err a -> void

def callback(value)

semaphore.pop

self.cache = Some.new(value)

while (subscribers.count > 0)

sub = self.subscribers.shift

Thread.new {

sub.call(value)

}

end

semaphore.push(nil)

end

# subscribe :: (Either err a -> void) -> void

def subscribe(subscriber)

semaphore.pop

if (self.cache.defined)

semaphore.push(nil)

subscriber.call(cache.value)

else

self.subscribers.push(subscriber)

semaphore.push(nil)

end

end

end

Swift—Future Monad

import Foundation

let background = DispatchQueue(label: "background", attributes: .concurrent)

class Future<Err, A> {

typealias Callback = (Either<Err, A>) -> Void

var subscribers: Array<Callback> = Array<Callback>()

var cache: Maybe<Either<Err, A>> = .None

var semaphore = DispatchSemaphore(value: 1)

lazy var callback: Callback = { value in

self.semaphore.wait()

self.cache = .Some(value)

while (self.subscribers.count > 0) {

let subscriber = self.subscribers.popLast()

background.async {

subscriber?(value)

}

}

self.semaphore.signal()

}

init(_ f: @escaping (@escaping Callback) -> Void) {

f(self.callback)

}

func subscribe(_ cb: @escaping Callback) {

self.semaphore.wait()

switch cache {

case .None:

subscribers.append(cb)

self.semaphore.signal()

case .Some(let value):

self.semaphore.signal()

cb(value)

}

}

static func pure<B>(_ value: B) -> Future<Err, B> {

return Future<Err, B> { $0(Either<Err, B>.pure(value)) }

}

func flatMap<B>(_ f: @escaping (A) -> Future<Err, B>) -> Future<Err, B> {

return Future<Err, B> { [weak self] cb in

guard let this = self else { return }

this.subscribe { value in

switch value {

case .Left(let err):

cb(Either<Err, B>.Left(err))

case .Right(let x):

f(x).subscribe(cb)

}

}

}

}

func map<B>(_ f: @escaping (A) -> B) -> Future<Err, B> {

return self.flatMap { Future<Err, B>.pure(f($0)) }

}

static func traverse<B>(_ list: Array<A>, _ f: @escaping (A) -> Future<Err, B>) -> Future<Err, Array<B>> {

return list.reduce(Future<Err, Array<B>>.pure(Array<B>())) { (acc: Future<Err, Array<B>>, elem: A) in

return acc.flatMap { elems in

return f(elem).map { val in

return elems + [val]

}

}

}

}

}

Scala—Future Monad

package monad

import java.util.concurrent.Semaphore

class MyFuture[A] {

private var subscribers: List[MyEither[Exception, A] => Unit] = List()

private var cache: MyOption[MyEither[Exception, A]] = MyNone

private val semaphore = new Semaphore(1)

def this(f: (MyEither[Exception, A] => Unit) => Unit) {

this()

f(this.callback _)

}

def flatMap[B](f: A => MyFuture[B]): MyFuture[B] =

Monad[MyFuture].flatMap(this)(f)

def map[B](f: A => B): MyFuture[B] =

Monad[MyFuture].map(this)(f)

def callback(value: MyEither[Exception, A]): Unit = {

semaphore.acquire

cache = MySome(value)

subscribers.foreach { sub =>

val t = new Thread(

new Runnable {

def run: Unit = {

sub(value)

}

}

)

t.start

}

subscribers = List()

semaphore.release

}

def subscribe(sub: MyEither[Exception, A] => Unit): Unit = {

semaphore.acquire

cache match {

case MyNone =>

subscribers = sub :: subscribers

semaphore.release

case MySome(value) =>

semaphore.release

sub(value)

}

}

}

object MyFuture {

def async[B, C](f: B => C, arg: B): MyFuture[C] =

new MyFuture[C]({ cb =>

val t = new Thread(

new Runnable {

def run: Unit = {

try {

cb(MyRight(f(arg)))

} catch {

case e: Exception => cb(MyLeft(e))

}

}

}

)

t.start

})

def traverse[A, B](list: List[A])(f: A => MyFuture[B]): MyFuture[List[B]] = {

list.foldRight(Monad[MyFuture].pure(List[B]())) { (elem, acc) =>

Monad[MyFuture].flatMap(acc) ({ values =>

Monad[MyFuture].map(f(elem)) { value => value :: values }

})

}

}

}

// ...

implicit val myFutureMonad = new Monad[MyFuture] {

def pure[A](a: A): MyFuture[A] =

new MyFuture[A]({ cb => cb(myEitherMonad[Exception].pure(a)) })

def flatMap[A, B](ma: MyFuture[A])(f: A => MyFuture[B]): MyFuture[B] =

new MyFuture[B]({ cb =>

ma.subscribe(_ match {

case MyLeft(e) => cb(MyLeft(e))

case MyRight(a) => f(a).subscribe(cb)

})

})

}

Notice how Future’s public API remains free of low-level details like threads, semaphores, etc. You simply provide something with a callback, and the monad takes care of the rest!

Composing a Program from Monads

Let’s build a program using our monads. We have a file containing a list of URLs and want to fetch them in parallel, truncate the responses to 200 bytes for brevity, and print the result.

First, we convert existing language APIs to monadic interfaces (using functions readFile and fetch). We then compose them into a chain to obtain the final result. Note that the chain itself remains exceptionally safe, as all the complex details are encapsulated within the monads.

JavaScript—Sample Monad Program

import { Future } from './future';

import { Either, Left, Right } from './either';

import { readFile } from 'fs';

import https from 'https';

const getResponse = url =>

new Future(cb => https.get(url, res => {

var body = '';

res.on('data', data => body += data);

res.on('end', data => cb(new Right(body)));

res.on('error', err => cb(new Left(err)))

}))

const getShortResponse = url => getResponse(url).map(resp => resp.substring(0, 200))

Future

.async(readFile, 'resources/urls.txt')

.map(data => data.toString().split("\n"))

.flatMap(urls => Future.traverse(urls)(getShortResponse))

.map(console.log)

Python—Sample Monad Program

import http.client

import threading

import time

import os

from future import Future

from either import Either, Left, Right

conn = http.client.HTTPSConnection("en.wikipedia.org")

def read_file_sync(uri):

base_dir = os.path.dirname(__file__) #<-- absolute dir the script is in

path = os.path.join(base_dir, uri)

with open(path) as f:

return f.read()

def fetch_sync(uri):

conn.request("GET", uri)

r = conn.getresponse()

return r.read().decode("utf-8")[:200]

def read_file(uri):

return Future.async(lambda: read_file_sync(uri))

def fetch(uri):

return Future.async(lambda: fetch_sync(uri))

def main(args=None):

lines = read_file("../resources/urls.txt").map(lambda res: res.splitlines())

content = lines.flat_map(lambda urls: Future.traverse(urls)(fetch))

output = content.map(lambda res: print("\n".join(res)))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Ruby—Sample Monad Program

require './lib/future'

require 'net/http'

require 'uri'

semaphore = Queue.new

def read(uri)

Future.async(-> () { File.read(uri) })

end

def fetch(url)

Future.async(-> () {

uri = URI(url)

Net::HTTP.get_response(uri).body[0..200]

})

end

read("resources/urls.txt")

.map(-> (x) { x.split("\n") })

.flat_map(-> (urls) {

Future.traverse(urls, -> (url) { fetch(url) })

})

.map(-> (res) { puts res; semaphore.push(true) })

semaphore.pop

Swift—Sample Monad Program

import Foundation

enum Err: Error {

case Some(String)

}

func readFile(_ path: String) -> Future<Error, String> {

return Future<Error, String> { callback in

background.async {

let url = URL(fileURLWithPath: path)

let text = try? String(contentsOf: url)

if let res = text {

callback(Either<Error, String>.pure(res))

} else {

callback(Either<Error, String>.Left(Err.Some("Error reading urls.txt")))

}

}

}

}

func fetchUrl(_ url: String) -> Future<Error, String> {

return Future<Error, String> { callback in

background.async {

let url = URL(string: url)

let task = URLSession.shared.dataTask(with: url!) {(data, response, error) in

if let err = error {

callback(Either<Error, String>.Left(err))

return

}

guard let nonEmptyData = data else {

callback(Either<Error, String>.Left(Err.Some("Empty response")))

return

}

guard let result = String(data: nonEmptyData, encoding: String.Encoding.utf8) else {

callback(Either<Error, String>.Left(Err.Some("Cannot decode response")))

return

}

let index = result.index(result.startIndex, offsetBy: 200)

callback(Either<Error, String>.pure(String(result[..<index])))

}

task.resume()

}

}

}

var result: Any = ""

let _ = readFile("\(projectDir)/Resources/urls.txt")

.map { data -> [String] in

data.components(separatedBy: "\n").filter { (line: String) in !line.isEmpty }

}.flatMap { urls in

return Future<Error, String>.traverse(urls) { url in

return fetchUrl(url)

}

}.map { responses in

print(responses)

}

RunLoop.main.run()

Scala—Sample Monad Program

import scala.io.Source

import java.util.concurrent.Semaphore

import monad._

object Main extends App {

val semaphore = new Semaphore(0)

def readFile(name: String): MyFuture[List[String]] =

MyFuture.async[String, List[String]](filename => Source.fromResource(filename).getLines.toList, name)

def fetch(url: String): MyFuture[String] =

MyFuture.async[String, String](

uri => Source.fromURL(uri).mkString.substring(0, 200),

url

)

val future = for {

urls <- readFile("urls.txt")

entries <- MyFuture.traverse(urls)(fetch _)

} yield {

println(entries)

semaphore.release

}

semaphore.acquire

}

There you have it—monad solutions in practice. You can find the complete code for this article on GitHub.

Overhead: Done. Benefits: Ongoing

While using monads for this simple program might seem like overkill, the initial setup remains constant in size. From now on, you can write extensive asynchronous code using monads without worrying about threads, race conditions, semaphores, exceptions, or null pointers!