Scala provides a concise and elegant syntax for writing both object-oriented and functional code, surpassing Java in terms of clarity (as an example). Case classes, higher-order functions, and the ability to infer types are just a few of the tools that Scala developers can utilize to create code that is more maintainable and less prone to errors.

However, even Scala code can become cluttered with boilerplate, leaving developers searching for ways to refactor and reuse such code effectively. For instance, certain libraries require developers to write repetitive code by calling an API for every subclass within a sealed class.

This remains true until developers discover the power of macros and quasiquotes, which allow them to generate this repetitive code automatically during compilation.

Use Case: Implementing a Shared Event Handler for Subtypes

While developing a microservices system, I needed to register a single event handler that would be invoked for all events derived from a particular base class. To avoid getting bogged down in framework-specific details, here’s a simplified representation of the API I was using for event handler registration:

| |

Given an event processor capable of handling any Event type, we can employ the addHandler method to register handlers for specific subclasses of Event.

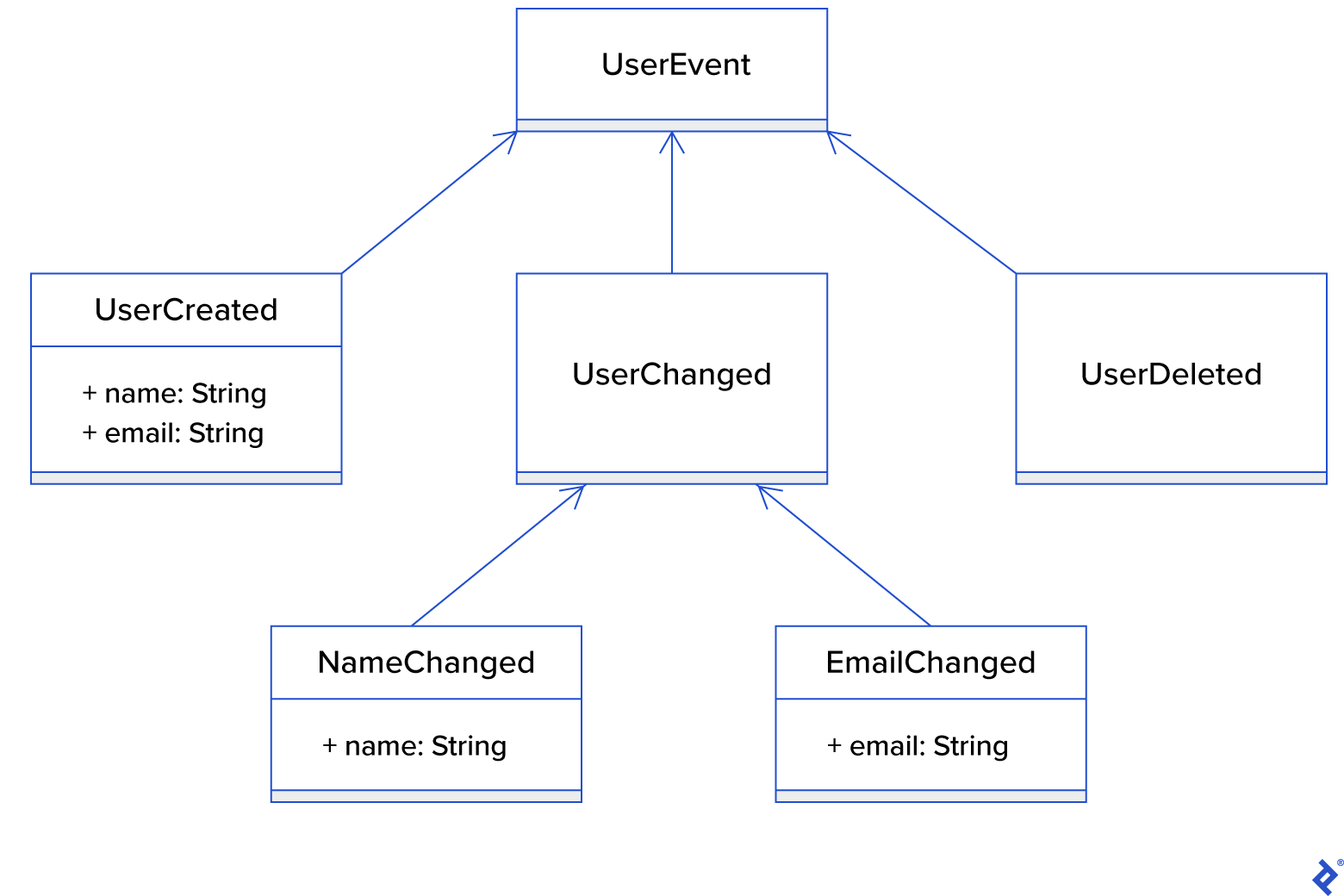

Observing the method signature above, a developer might reasonably assume that a handler registered for a particular type would also be triggered for events belonging to its subtypes. As an example, let’s examine the following class hierarchy representing events related to the lifecycle of a User entity:

The equivalent Scala declarations are as follows:

| |

While we can register a handler for each individual event class, what if we want to register a single handler for all event classes? My initial approach was to register the handler for the UserEvent class, expecting it to be invoked for all its subtypes.

| |

However, during testing, I observed that the handler was never invoked. This prompted me to investigate the code of Lagom, the framework I was using.

My investigation revealed that the event processor stored the registered handlers in a map, using the registered class as the key. Upon emitting an event, the processor would search for its class in the map to retrieve the corresponding handler. The implementation of the event processor followed this pattern:

| |

Since I had registered the handler for the UserEvent class, the processor couldn’t find a matching handler when a derived event like UserCreated was emitted.

The Emergence of Boilerplate

The solution was to register the same handler explicitly for each concrete event class, as demonstrated below:

| |

While this code now functions as intended, it introduces undesirable repetition.

This repetitive code is difficult to maintain, as any new event type would necessitate modifications in multiple places. Moreover, similar code patterns might exist elsewhere in the codebase, requiring consistent updates.

The situation is less than ideal, especially since UserEvent is a sealed class. This means that all its direct subclasses are known at compile time. It seems intuitive that we should be able to leverage this information to eliminate the boilerplate.

Enter Scala Macros

Unlike regular Scala functions, which return values based on parameters passed at runtime, Scala macros operate differently. These special functions generate code during the compilation process, replacing their invocations with the generated code.

Although the macro interface appears to accept values as parameters, its implementation actually captures the abstract syntax tree (AST) of these parameters. The AST represents the internal structure of the source code, which the compiler uses for analysis. The macro then utilizes this AST to generate a new AST, which ultimately replaces the original macro call during compilation.

Let’s define a macro that generates event handler registration code for all known subclasses of a given class:

| |

Observe that each parameter, including the type parameter and return type, has a corresponding AST expression in the implementation method. For instance, c.Expr[EventProcessor[Event]] corresponds to EventProcessor[Event]. The c: Context parameter provides access to the compilation context, allowing us to retrieve information available at compile time.

In our scenario, we need to obtain the children of our sealed class:

| |

The recursive call to the subclasses method ensures that we process not only the direct subclasses but also any indirect ones.

With the list of event classes to register in hand, we can proceed to construct the AST for the code that our Scala macro will generate.

Generating Scala Code: Choosing Between ASTs and Quasiquotes

When it comes to building our AST, we have two options: we can either manipulate AST classes directly or utilize Scala quasiquotes. While the former can lead to code that is verbose and difficult to maintain, quasiquotes provide a more elegant solution. They allow us to use a syntax that closely resembles the generated code, significantly reducing complexity.

To illustrate the contrast, consider the expression a + 2. Generating this using AST classes results in the following code:

| |

Quasiquotes achieve the same result with a more concise and readable syntax:

| |

To maintain the clarity of our macro, we will opt for quasiquotes.

Let’s define the AST and return it as the result of our macro function:

| |

This code begins with the processor expression received as a parameter. For each subclass of Event, it generates a call to the addHandler method, passing the subclass and the handler function as arguments.

We can now invoke the macro on the UserEvent class, which will generate the necessary code to register the handler for all its subclasses:

| |

This invocation will result in the generation of the following code:

| |

The code within the complete project now compiles successfully, and our test cases confirm that the handler is registered for each subclass of UserEvent. This approach instils confidence in our code’s ability to handle new event types gracefully.

Letting Scala Macros Handle Repetitive Code

Although Scala’s concise syntax generally helps avoid boilerplate, there are instances where code repetition becomes unavoidable and refactoring for reuse proves challenging. Scala macros, combined with the expressiveness of quasiquotes, offer a powerful mechanism to address such situations, ensuring that Scala code remains clean, maintainable, and free of unnecessary repetition.

Furthermore, there are widely used libraries, such as Macwire, that leverage the capabilities of Scala macros to assist developers in generating code efficiently. I highly recommend that every Scala developer explore this language feature, as it can be an invaluable asset a valuable asset.