Let’s start with a simple definition: Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) techniques allow us to generate samples from a distribution even when directly computing it is impossible.

What does this mean exactly? Let’s step back and discuss Monte Carlo Sampling.

Monte Carlo Sampling

What are Monte Carlo methods?

“Monte Carlo methods, or Monte Carlo experiments, are a broad class of computational algorithms that rely on repeated random sampling to obtain numerical results.” (Wikipedia)

Let’s simplify this.

Example 1: Area Estimation

Imagine you have an irregular shape, like the one shown below:

Your task is to calculate the area of this shape. One way is to divide it into small squares, count them, and get a decent approximation. However, this can be tedious and time-consuming.

This is where Monte Carlo sampling comes in!

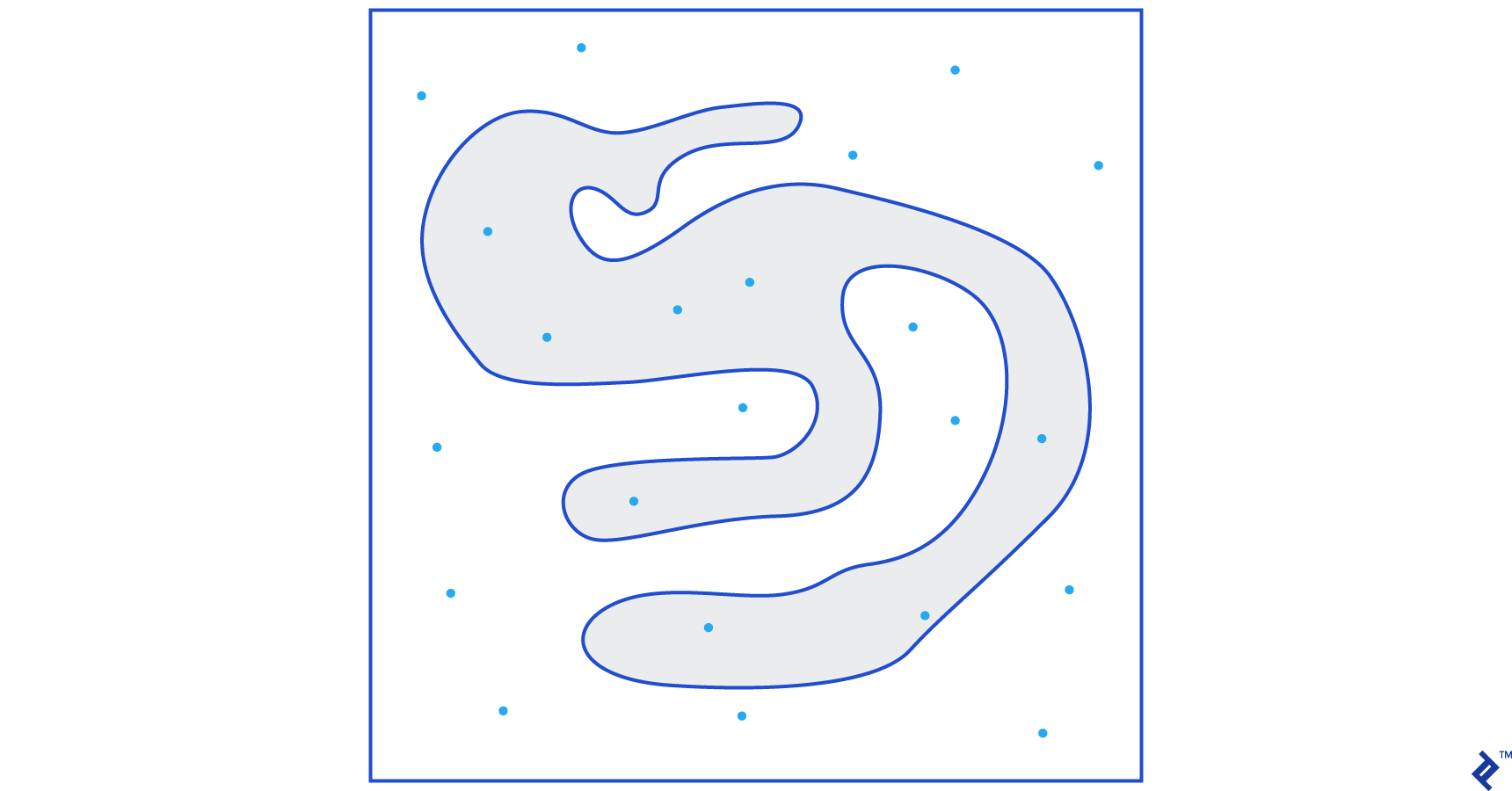

First, we enclose the shape within a larger square of a known area, say 50 cm2. Then, we randomly “throw darts” at this square.

We then count the total darts within the larger square and those landing inside our shape. Suppose we threw 100 darts and 22 landed inside the shape. We can now approximate the area using a simple formula:

area of shape = area of square *(number of darts in the shape) / (number of darts in the square)

In our case, this becomes:

area of shape = 50 * 22/100 = 11 cm2

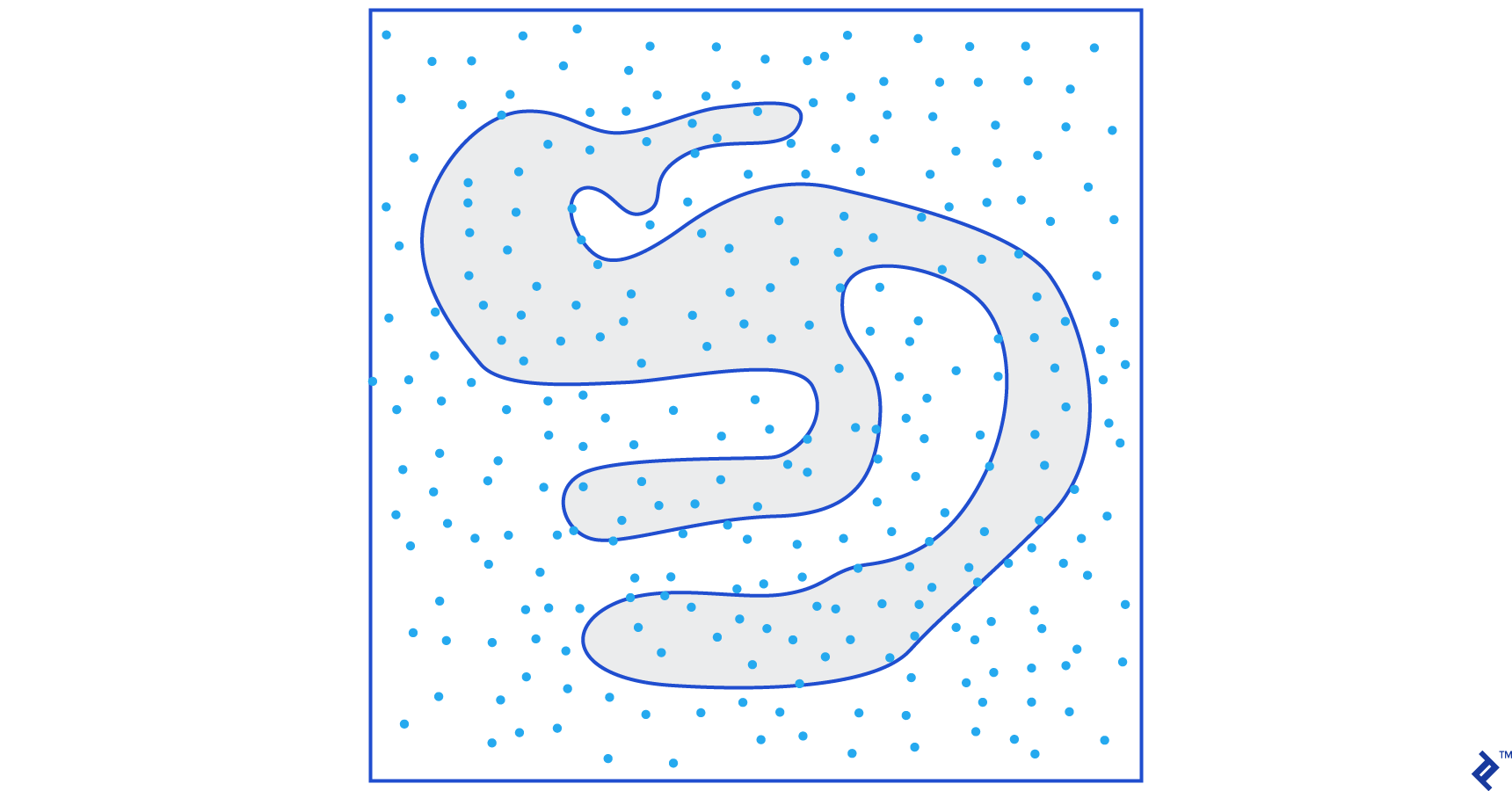

Increasing the “darts” tenfold improves the accuracy:

area of shape = 50 * 280/1000 = 14 cm2

This illustrates how Monte Carlo sampling simplifies complex problems like this.

The Law of Large Numbers

The area estimation improved with more darts due to the Law of Large Numbers:

“The law of large numbers is a theorem that describes the result of performing the same experiment a large number of times. According to the law, the average of the results obtained from a large number of trials should be close to the expected value, and will tend to become closer as more trials are performed.”

Let’s move on to another example, the famous Monty Hall problem.

Example 2: The Monty Hall Problem

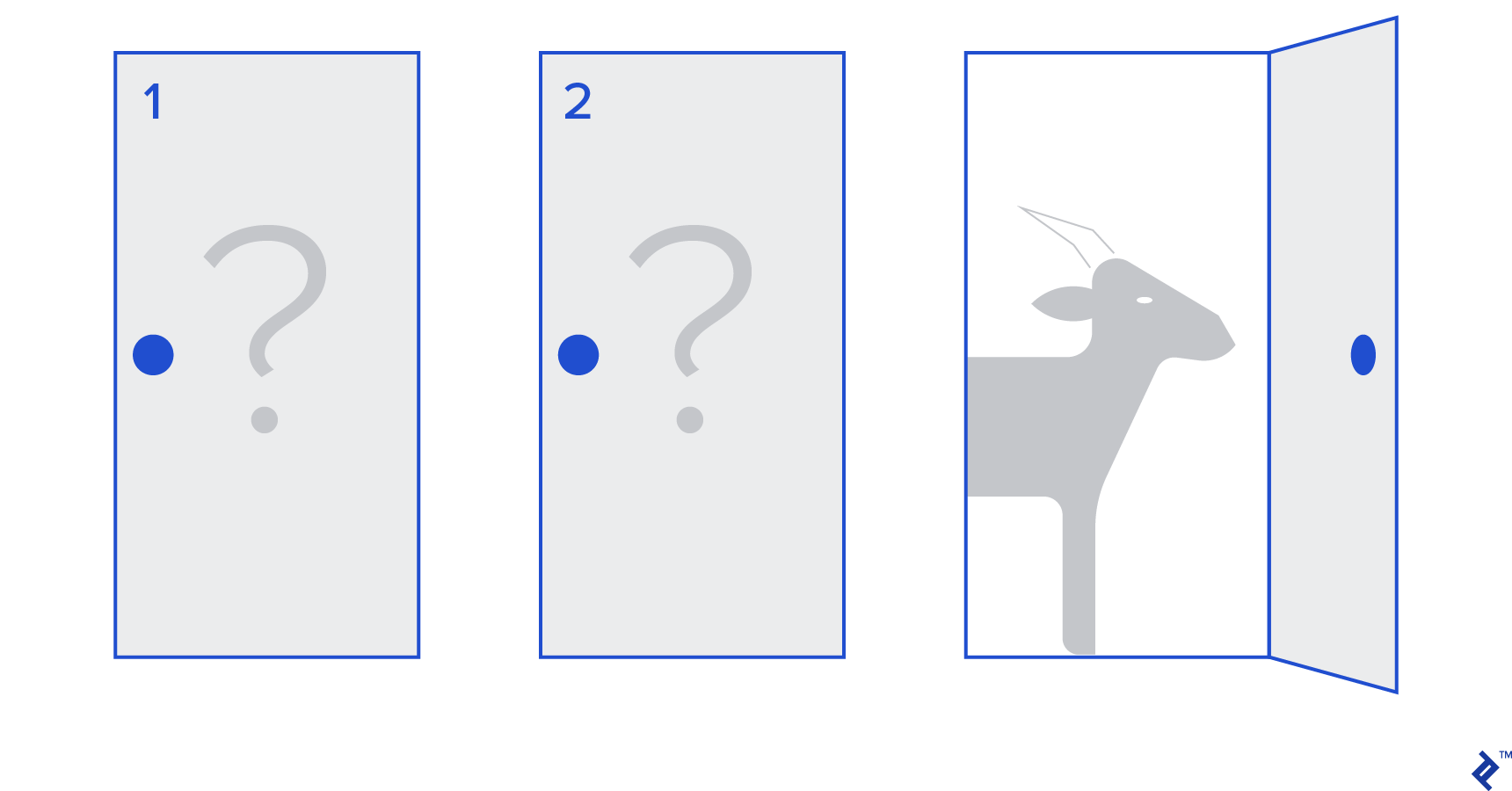

The Monty Hall problem is a well-known brain teaser:

“There are three doors, one has a car behind it, the others have a goat behind them. You choose a door, the host opens a different door, and shows you there’s a goat behind it. He then asks you if you want to change your decision. Do you? Why? Why not?”

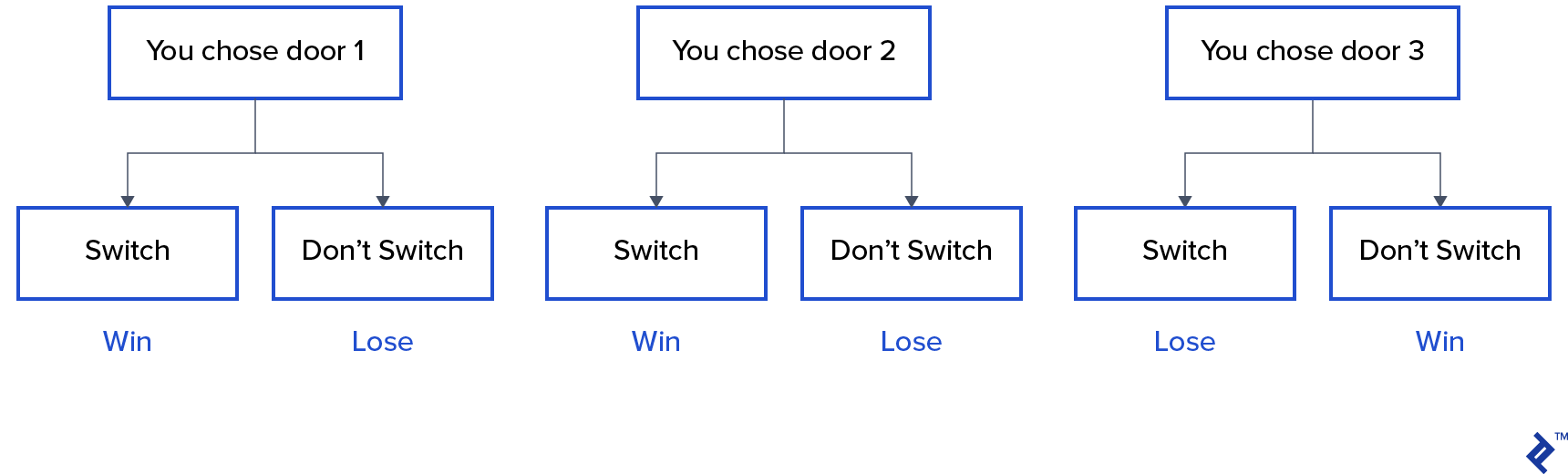

It seems like the chances of winning are equal whether you switch doors or not, but that’s not the case. A simple flowchart illustrates this:

Assuming the car is behind door 3:

Switching doors wins ⅔ of the time, while sticking with the initial choice only wins ⅓ of the time.

Let’s simulate this using sampling:

| |

The assign_car_door() function randomly selects a door (0, 1, or 2) to hide the car behind. assign_door_to_open chooses a door with a goat behind it, different from your pick, for the host to open. win_or_lose returns true or false based on whether you win the car, depending on if you “switch” doors.

Running this simulation 10 million times:

- Probability of winning without switching: 0.334134

- Probability of winning with switching: 0.667255

These results closely match the flowchart’s predictions.

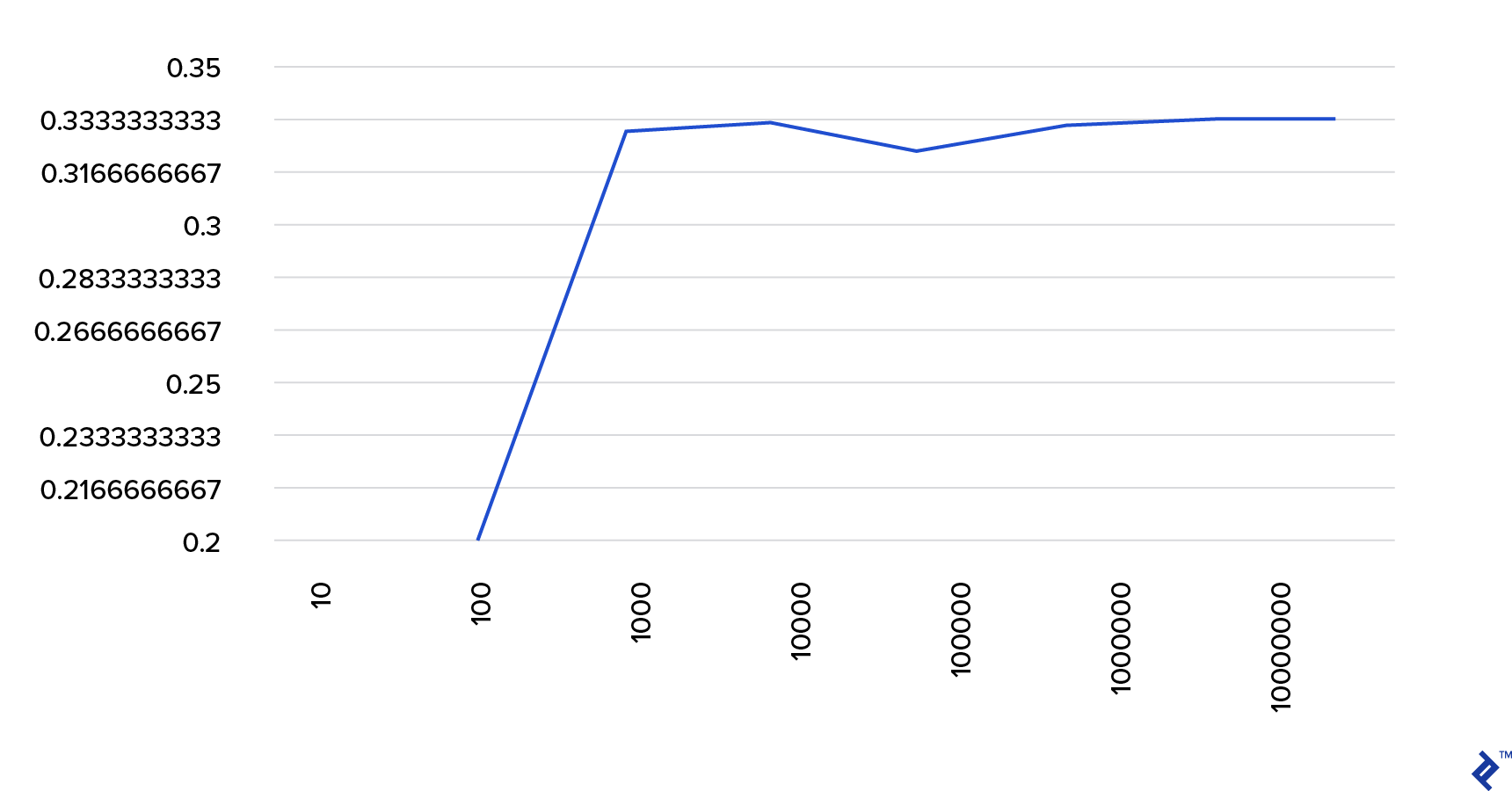

The more simulations we run, the closer the results get to the true probabilities, confirming the law of large numbers:

This table further demonstrates this:

| Simulations run | Probability of winning if you switch | Probability of winning if you don't switch |

| 10 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| 10^2 | 0.63 | 0.33 |

| 10^3 | 0.661 | 0.333 |

| 10^4 | 0.6683 | 0.3236 |

| 10^5 | 0.66762 | 0.33171 |

| 10^6 | 0.667255 | 0.334134 |

| 10^7 | 0.6668756 | 0.3332821 |

The Bayesian Approach

“Frequentist, known as the more classical version of statistics, assume that probability is the long-run frequency of events (hence the bestowed title).”

“Bayesian statistics is a theory in the field of statistics based on the Bayesian interpretation of probability where probability expresses a degree of belief in an event. The degree of belief may be based on prior knowledge about the event, such as the results of previous experiments, or on personal beliefs about the event.” - from Probabilistic Programming and Bayesian Methods for Hackers

What does this mean in simpler terms?

Frequentist thinking considers probabilities in the long run. A 0.001% chance of a car crash means that out of countless car trips, 0.001% would likely result in a crash.

Bayesian thinking is different. It starts with a prior belief. A belief of 0 means you’re certain an event won’t happen, while a belief of 1 means you’re sure it will.

As we observe data, we update this prior belief accordingly. This is done using Bayes theorem.

Bayes Theorem

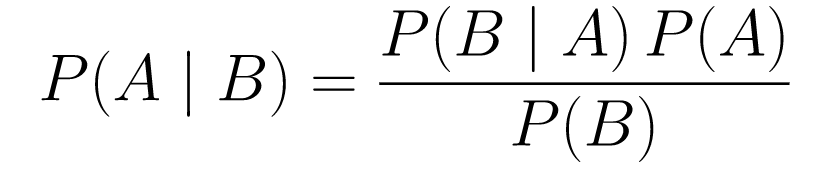

Let’s break this down.

P(A | B)is the probability of event A happening given that event B has already occurred. This is the posterior probability. B represents observed data, so it tells us the probability of A given the data.P(A)is the prior probability, our initial belief in event A happening.P(B | A)is the likelihood, the probability of observing data B if A is true.

Let’s consider an example: cancer screening.

Probability of Cancer

A patient gets a mammogram, and the result is positive. What’s the probability of actually having cancer?

Let’s define the probabilities:

- 1% of women have breast cancer.

- Mammograms detect cancer 80% of the time when present.

- 9.6% of mammograms are false positives.

It’s incorrect to assume an 80% chance of having cancer just because of a positive mammogram. This ignores the prior knowledge that cancer is rare (1% occurrence). We need to incorporate this prior using Bayes’ theorem:

P(C+ | T+) =(P(T+|C+)*P(C+))/P(T+)

P(C+ | T+): Probability of having cancer given a positive test (what we want).P(T+ | C+): Probability of a positive test given cancer (80% or 0.8).P(C+): Prior probability of having cancer (1% or 0.01).P(T+): Probability of a positive test, calculated as: _P(T+) = P(T+|C-)_P(C-)+P(T+|C+)P(C+)P(T+ | C-): Probability of a false positive (9.6% or 0.096).P(C-): Probability of not having cancer (99% or 0.99).

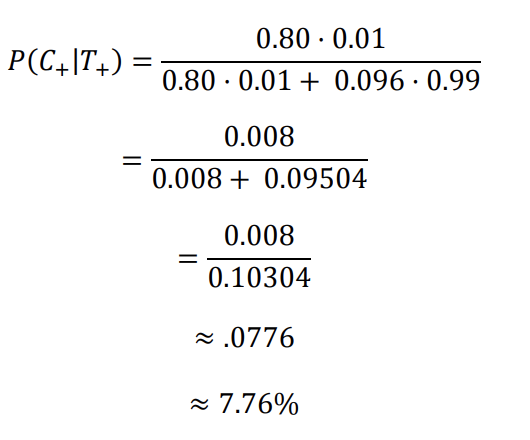

Plugging these values into the formula:

So, a positive mammogram translates to a 7.76% chance of having cancer. This makes sense considering the high false positive rate (9.6%) leads to many false positives within a population. For rare diseases, most positive results will be false.

Now, let’s revisit the Monty Hall problem using Bayes’ theorem.

Monty Hall Problem

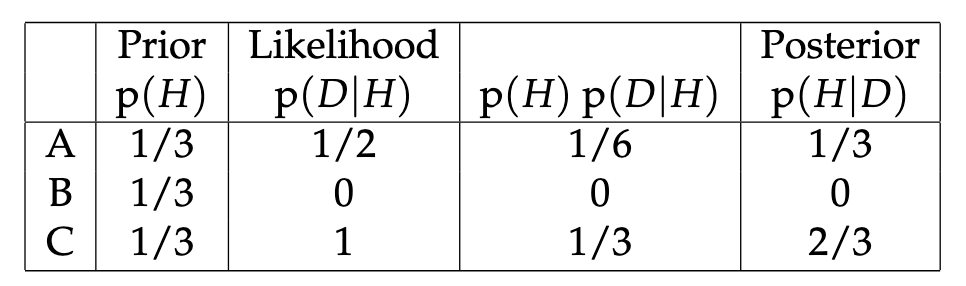

Priors:

- You initially choose door A.

- P(H) = ⅓ for all doors (equal chance of hiding the car).

Likelihood:

P(D|H): Monty opens door B revealing a goat.P(D|H)= ½ if the car is behind door A (50% chance of choosing B or C).P(D|H)= 0 if the car is behind door B (can’t open the door with the car).P(D|H)= 1 if the car is behind door C (forced to open B).

We want to know P(H|D): probability of the car being behind each door given Monty’s action.

The posterior P(H|D) shows that switching to door C from A increases the probability of winning.

Metropolis-Hastings

Let’s combine what we’ve learned to understand how Metropolis-Hastings works.

Metropolis-Hastings utilizes Bayes’ theorem to approximate the posterior distribution of a complex distribution, especially those difficult to sample from directly.

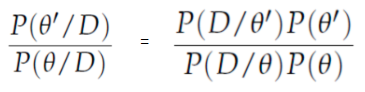

How? It randomly picks samples from a space and compares the probability of the new sample belonging to the posterior with that of the previous sample. Since we’re looking at the ratio of probabilities, P(B) from equation (1) cancels out:

P(acceptance) = ( P(newSample) * Likelihood of new sample) / (P(oldSample) * Likelihood of old sample)

The function f determines the “likelihood” of each new sample. f must be proportional to the desired posterior distribution.

To determine if a new proposed θ′ should be accepted or rejected, this ratio is calculated:

Where θ is the old sample, P(D| θ) is the likelihood of sample θ.

Let’s illustrate this with an example. You have data and want to find the normal distribution that best fits it:

X ~ N(mean, std)

We’ll define priors for both the mean and standard deviation. For simplicity, assume both follow a normal distribution with mean 1 and standard deviation 2:

Mean ~ N(1, 2) std ~ N(1, 2)

Let’s generate some data with a true mean of 0.5 and a standard deviation of 1.2:

| |

PyMC3

We’ll use the PyMC3 library to model the data and find the posterior distribution for the mean and standard deviation.

| |

Explanation:

- We define the priors for the mean and standard deviation (normal distribution with mean 1 and standard deviation 2).

x = pm.Normal(“X”, mu = mean, sigma = std, observed = X)defines the variable of interest, incorporating the defined mean, standard deviation, and the generated data.

Results:

| |

The estimated standard deviation is centered around 1.2, and the mean is around 1.55, which are close to the true values!

Let’s now implement Metropolis-Hastings from scratch for a deeper understanding.

From Scratch

Generating a Proposal

How does Metropolis-Hastings choose which sample to pick?

It uses a proposal distribution, a normal distribution centered at the current accepted sample with a standard deviation (hyperparameter) that we can adjust. A larger standard deviation leads to a wider search from the current sample. Let’s code this:

This function takes the current mean and standard deviation and proposes new values for both.

| |

Accepting/Rejecting a Proposal

Let’s code the acceptance/rejection logic. It involves two parts: prior and likelihood.

Calculating the probability of the proposal coming from the prior:

| |

This calculates how likely the proposed mean and standard deviation are to belong to the defined prior distribution.

Calculating the likelihood, how well the observed data fits the proposed distribution:

| |

We multiply the probability of each data point belonging to the proposed distribution.

Now, we call these functions for both the current and proposed mean and standard deviation:

| |

The complete code:

| |

Finally, let’s create the function to generate the posterior samples.

Generating the Posterior

Putting everything together to generate the posterior:

| |

Room for Improvement

Logarithms are useful!

Remember: a * b = antilog(log(a) + log(b)) and a / b = antilog(log(a) - log(b)).

This is helpful when dealing with very small probabilities, as multiplying them might lead to zero. Instead, we can add their logarithms to avoid this.

Our code becomes:

| |

Since we’re now using the log of the acceptance probability:

if np.random.rand() < acceptance_prob:

Becomes:

if math.log(np.random.rand()) < acceptance_prob:

Running the updated code and plotting the results:

| |

The estimated standard deviation is centered around 1.2, and the mean is around 1.5. We did it!

Moving Forward

You now understand how Metropolis-Hastings works and might wonder about its applications.

Bayesian Methods for Hackers is an excellent resource for probabilistic programming. To explore Bayes’ theorem and its applications further, check out Think Bayes by Allen B. Downey.

Thank you for reading. I hope this encourages you to delve into the fascinating world of Bayesian statistics.