It’s common to hear that metaprogramming is a technique reserved for Ruby experts and beyond the reach of everyday programmers. However, this is far from the truth. This blog post aims to debunk this misconception and make metaprogramming accessible to the average Ruby developer, allowing them to harness its power.

It’s important to note that metaprogramming can have a broad meaning and its usage can be prone to misuse and extremes. Therefore, I’ll focus on providing practical examples that demonstrate its everyday applications in programming.

Metaprogramming

Metaprogramming is a technique that allows you to write code that dynamically generates other code at runtime. This means you can define methods and classes on the fly. While it might sound complex, it essentially enables you to modify existing classes, handle non-existent methods by creating them dynamically, write more concise and DRY code by reducing repetition, and much more.

The Basics

Let’s start with the fundamentals of metaprogramming through an example. Consider the following code:

| |

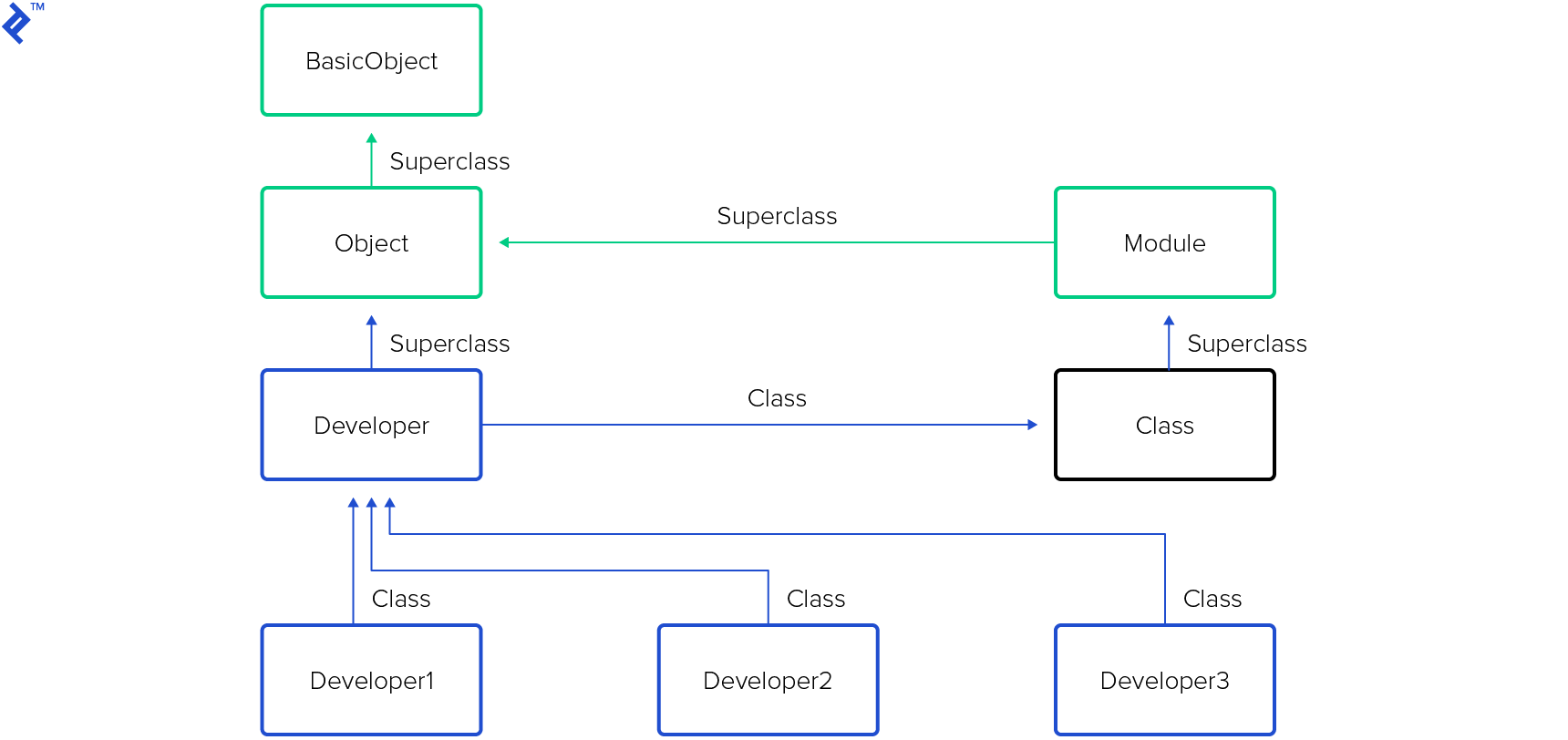

We’ve defined a class with two methods: a class method and an instance method. This is fundamental Ruby, but there’s a lot happening under the hood that we need to understand. It’s crucial to remember that the Developer class itself is an object. In Ruby, everything is treated as an object, including classes. Since Developer is an instance, it’s an instance of the Class class. Here’s a representation of the Ruby object model:

| |

Understanding the significance of self is key. The frontend method is a standard instance method available to Developer instances. However, the backend method is a class method. This is because every line of Ruby code is executed within a specific context, represented by self. The value of self points to the current object, which can vary depending on the code being executed. For instance, inside a class definition, self references the class itself, which is an instance of the Class class.

| |

Within instance methods, self refers to an instance of the class.

| |

Within class methods, self refers to the class itself, the specifics of which will be discussed later in this article:

| |

This brings us to the concept of a class method. Before delving into that, we need to introduce metaclasses, also known as singleton classes or eigenclasses. The frontend class method we defined earlier is simply an instance method defined within the metaclass associated with the Developer object! A metaclass is a class that Ruby automatically creates and inserts into the inheritance hierarchy to house class methods, ensuring they don’t interfere with instances of the class.

Metaclasses

Every object in Ruby possesses its own metaclass, which is hidden from the developer but accessible. Since our Developer class is ultimately an object, it has its own metaclass. Let’s illustrate this by creating a String object and manipulating its metaclass:

| |

Here, we’ve added a singleton method called something to the object. Unlike class methods, which are accessible to all instances of a class, singleton methods are specific to a single instance. Class methods are commonly used, while singleton methods are less prevalent. However, both types of methods are added to the object’s metaclass.

The previous example can be rewritten as follows:

| |

Despite the syntax difference, both achieve the same outcome. Now, let’s revisit our Developer class example and explore different ways to define a class method:

| |

This is the standard definition used by most developers.

| |

This is equivalent to the previous definition. We define the backend class method for Developer without explicitly using self. Defining a method in this manner automatically makes it a class method.

| |

Here, we define a class method using syntax similar to defining a singleton method for a String object. Note the use of self, which refers to the Developer object. We open the Developer class, making self equal to the Developer class. Next, we use class << self, setting self to Developer’s metaclass. Finally, we define the backend method within Developer’s metaclass.

| |

This block sets self to Developer’s metaclass for its duration. Consequently, the backend method is added to Developer’s metaclass instead of the class itself.

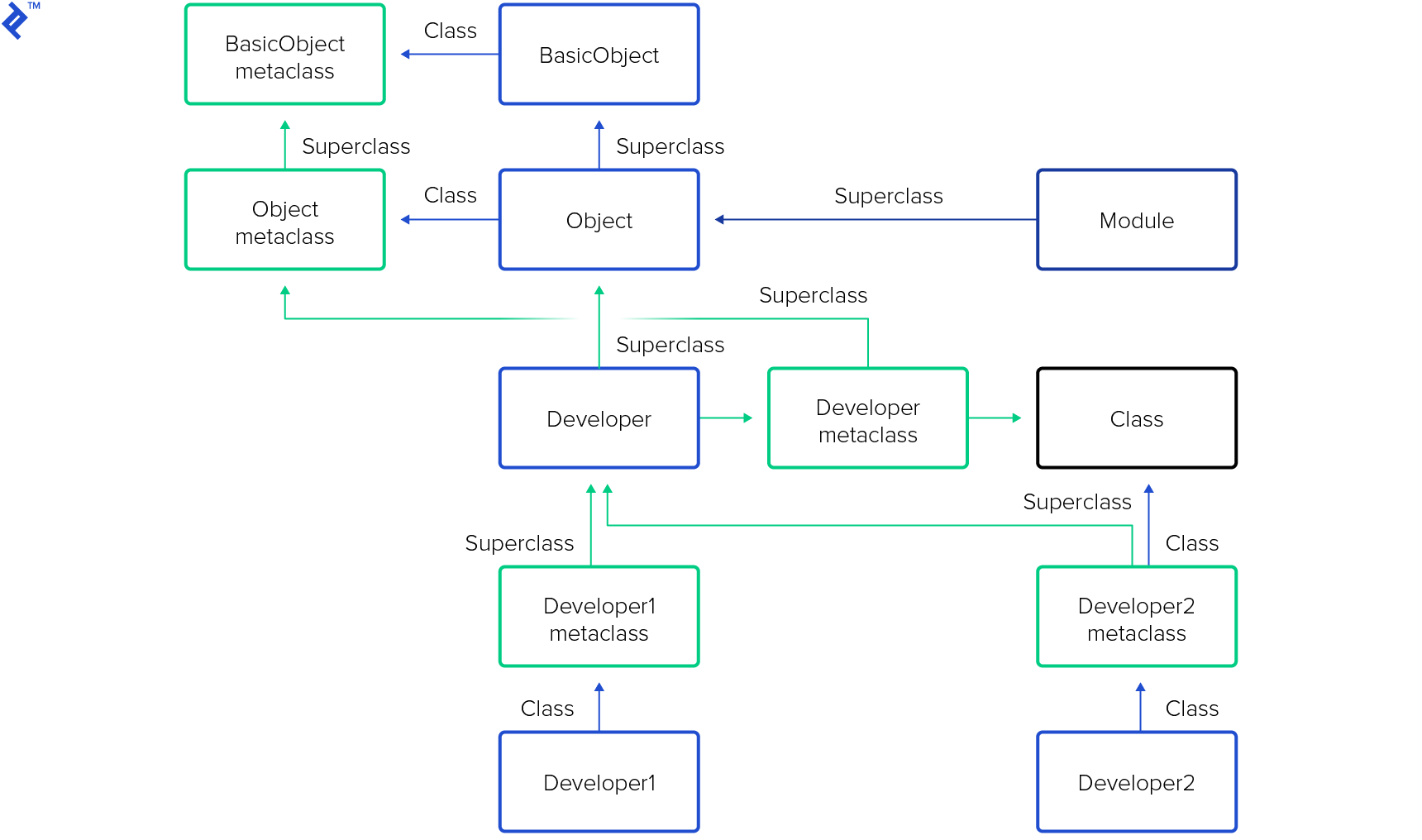

Let’s examine how the metaclass behaves within the inheritance tree:

Previous examples haven’t provided concrete evidence of the metaclass’s existence. However, we can use a trick to reveal this hidden class:

| |

We define an instance method within the Object class. Inside this method, self refers to the Object object. We then use class << self to change the current self to point to the metaclass of the current object. Since the current object is the Object class, this would be the instance’s metaclass. The method returns self, which represents the metaclass. By calling this instance method on any object, we can obtain its metaclass. Let’s recreate our Developer class and explore further:

| |

To demonstrate that frontend is an instance method of a class and backend is an instance method of a metaclass, consider the following:

| |

It’s important to note that you don’t need to reopen Object and add this hack to access the metaclass. Ruby provides the singleton_class method for this purpose. While functionally equivalent to our metaclass_example hack, it provides insights into Ruby’s internal workings:

| |

Defining Methods Using “class_eval” and “instance_eval”

Another way to create a class method is using instance_eval:

| |

The Ruby interpreter evaluates this code within the context of an instance, which is the Developer object in this case. When defining a method on an object, you create either a class method or a singleton method. In this instance, it’s a class method—more precisely, class methods are singleton methods of a class, while others are singleton methods of an object.

Conversely, class_eval evaluates code within the context of a class instead of an instance. It effectively reopens the class. Here’s how class_eval can be used to create an instance method:

| |

In essence, class_eval changes self to refer to the original class, while instance_eval changes self to refer to the original class’s metaclass.

Defining Missing Methods on the Fly

Another crucial aspect of metaprogramming is the concept of method_missing. When a method is called on an object, Ruby searches for the method within the class’s instance methods. If not found, it continues up the ancestors chain. If the method remains unfound, Ruby calls the method_missing method, an instance method of Kernel inherited by every object. Since Ruby consistently calls this method for missing methods, we can leverage it for various purposes.

define_method is a method defined in the Module class used for dynamic method creation. It takes the new method’s name and a block, where the block’s parameters become the new method’s parameters. While both def and define_method create methods, define_method can be used in conjunction with method_missing to write DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) code. More specifically, define_method can manipulate scopes when defining a class, but that’s beyond the scope of this discussion. Let’s illustrate with a simple example:

| |

This demonstrates how define_method creates an instance method without using def. However, we can achieve much more. Consider this code snippet:

| |

This code is not DRY. We can improve it using define_method:

| |

This is better but not perfect. If we want to add a new method, such as coding_debug, we need to manually add "debug" to the array. We can address this using method_missing:

| |

Let’s break down this code. Calling a non-existent method triggers method_missing. We only want to create a new method if the method name starts with "coding_". Otherwise, we call super to handle the truly missing method. We use define_method to create the new method. This allows us to create numerous methods starting with "coding_", making our code significantly DRYer. Since define_method is private to Module, we use send to invoke it.

Wrapping up

This is just a glimpse into the world of metaprogramming. To become a Ruby expert, mastering these building blocks is essential. Once you grasp these concepts, you can explore more advanced topics like creating your own Domain-Specific Language (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain-specific_language) (DSL). While DSLs are a separate topic altogether, these fundamental concepts are crucial for understanding them. Many widely used gems in Rails, such as RSpec and ActiveRecord, are built using DSLs, which you’ve likely used without realizing it.

Hopefully, this article provides a stepping stone towards understanding metaprogramming and perhaps even building your own DSLs, enabling you to write more efficient and expressive code.