Getting started with React is fairly easy, as the first part of this tutorial demonstrated. Simply use Create React App (CRA) to initialize a project and begin coding. However, as your project grows, managing your code can become challenging, especially if you’re new to React. Components might become unnecessarily large, or you might have elements that should be components but aren’t, leading to repetitive code.

This is where you should begin thinking in terms of React development solutions.

When starting a new application or design that will eventually become a React application, first identify the components in your sketch, determine how to separate them for better management, and identify repetitive elements (or their behavior). Resist adding code that might be “useful in the future." While tempting, that future may never arrive, and you’ll be stuck with extra generic functions or components with numerous configurable options.

Additionally, consider separating components longer than 2-3 window heights (if feasible) for improved readability.

Controlled vs. Uncontrolled Components in React

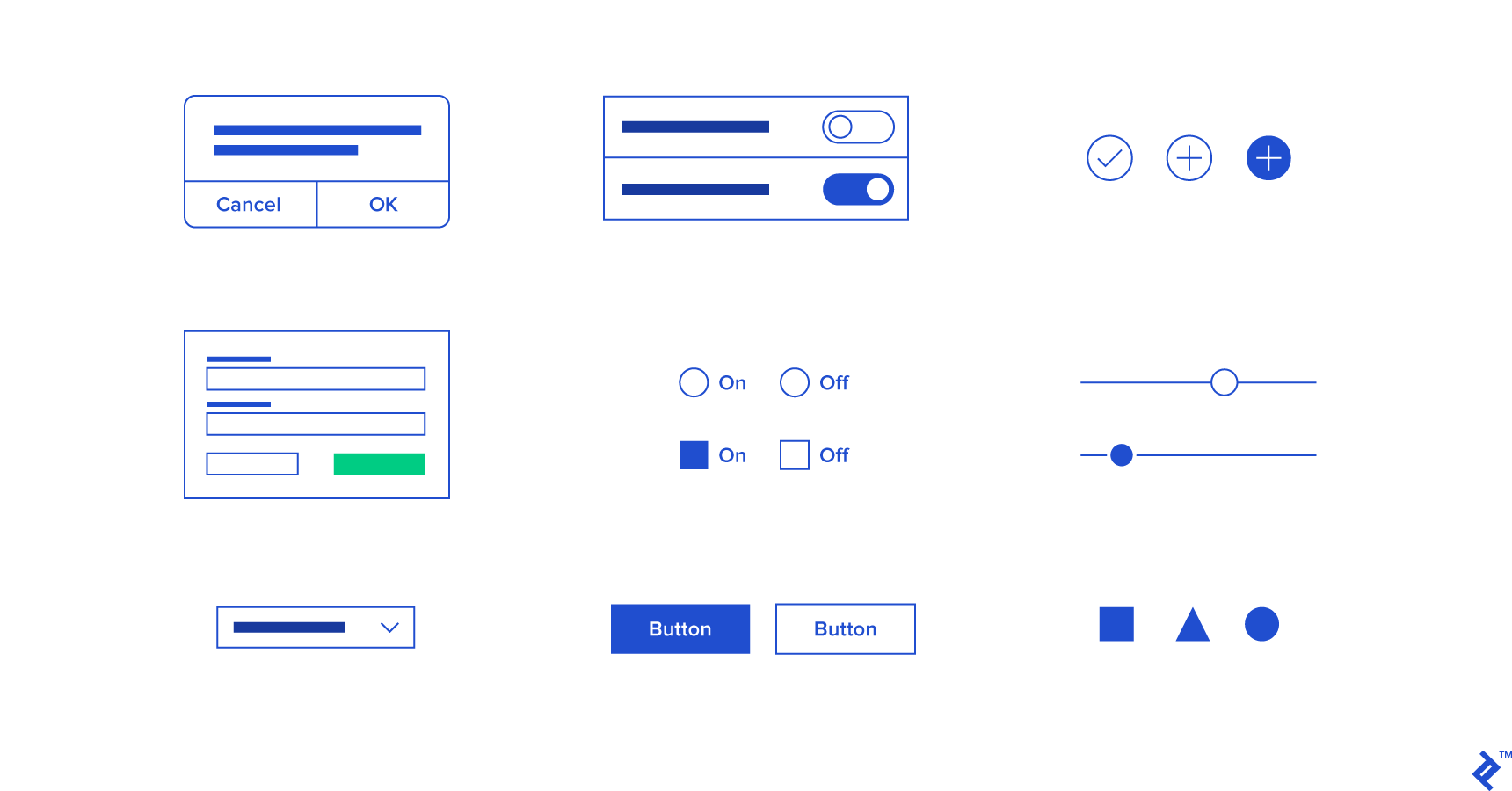

Most applications require user input and interaction, enabling users to enter text, upload files, select fields, and more. React handles user interaction in two ways: controlled and uncontrolled components.

Controlled components, as the name implies, are managed by React. React provides a value to the user-interactive element, while uncontrolled elements don’t receive a value property. This ensures a single source of truth (the React state), preventing discrepancies between what’s displayed and the current state. Developers need to pass a function that reacts to user interaction with a form, updating its state.

| |

With uncontrolled components, we don’t directly manage value changes. To access the current value, we use refs.

| |

So, which approach should you choose? In most scenarios, controlled components are preferred, but exceptions exist. One such instance is the file type input, where the value is read-only and requires user interaction for modification. Controlled components are generally more readable and easier to work with. Validation relies on re-rendering, the state can be updated easily, and input errors (e.g., format or empty fields) can be indicated directly.

Refs

Previously mentioned, refs offer a special feature available in class components before hooks were introduced in version 16.8.

Refs provide developers access to a React component or DOM element (depending on where the ref is attached) through a reference. However, it’s best practice to minimize their use and reserve them for essential scenarios, as they can hinder code readability and disrupt the top-down data flow. Nevertheless, there are situations where refs are necessary, particularly with DOM elements (e.g., programmatically changing focus). When attached to a React component element, you can use methods from the referenced component. However, this practice should be avoided, as there are better alternatives (e.g., lifting state up and moving functions to parent components).

There are three ways to implement refs:

- Using a string literal (legacy and discouraged),

- Using a callback function set in the

refattribute, - Creating a ref with

React.createRef()and binding it to a class property for access (references become available from thecomponentDidMountlifecycle).

Additionally, there are cases where refs are not passed down and instances where you need to access a deeply nested reference element from the current component. For example, imagine you have a <Button> component containing an <input> DOM element, and you’re currently in a <Row> component. To access the input’s DOM focus function from the <Row> component, you would use forwardRef).

One scenario where references are not passed down is when a higher order component is applied to a component. This occurs because ref is not a prop (similar to key) and is not passed down, so it references the HOC instead of the wrapped component. To address this, we can utilize React.forwardRef, which takes props and refs as arguments, allowing us to assign them to prop and pass them down to the desired component.

| |

Error Boundaries

As complexity increases, the likelihood of errors also rises. This is where error boundaries in React come into play. So how do they function?

If an error occurs and there’s no error boundary as its parent, the entire React application will crash. While it’s preferable to display no information than to mislead users with incorrect data, crashing the entire application and displaying a blank screen isn’t always desirable. Error boundaries offer increased flexibility, allowing you to either implement one globally to display a generic error message or use them for specific widgets to either hide them or display alternative content.

It’s important to note that error boundaries only handle errors within declarative code, not imperative code (e.g., event handlers or function calls). For imperative code, the traditional try/catch approach should be used.

Error boundaries also provide a mechanism to send error information to your chosen Error Logger within the componentDidCatch lifecycle method.

| |

Higher Order Components

Higher Order Components (HOCs) are a widely discussed and frequently used pattern in React. If you’re familiar with HOCs, you’ve likely encountered patterns like withNavigation, connect, and withRouter in various libraries.

HOCs are functions that accept a component as an argument and return a new component with enhanced capabilities. This enables the creation of easily extensible functions that enrich components (e.g., providing access to navigation). HOCs can take different forms depending on the implementation. While a component argument is always required, they can accept additional arguments, such as options. For instance, in connect, you first invoke a function with configurations, which returns another function that accepts a component argument and returns the HOC.

Here are a few recommendations and things to avoid when working with HOCs:

- Provide a descriptive display name for your wrapper HOC function (to easily identify it as an HOC).

- Avoid using HOCs inside render methods. Use the enhanced component directly to prevent unnecessary re-mounting and state loss.

- Static methods are not automatically copied, so manually copy any static methods from the original component to the HOC.

- As mentioned earlier, Refs are not passed down, so employ

React.forwardRefto address this.

| |

Styling

While not directly related to React itself, styling deserves mention for several reasons.

Firstly, both regular CSS and inline styles function as expected. You can apply class names from CSS files using the className attribute, and inline styles work similarly to regular HTML styling. However, instead of passing a style string, React uses objects with specific style values. Style attributes are also camelCased (e.g., border-radius becomes borderRadius).

React has popularized some styling solutions that have become widely adopted, such as CSS Modules, which are now integrated into CRA. With CSS Modules, you import stylesheets like name.modules.css and use the class names as properties to style your components. Some IDEs (e.g., WebStorm) even offer autocomplete for CSS Modules, suggesting available class names.

Another popular solution in React is CSS-in-JS (e.g., the emotion library). It’s important to reiterate that both CSS Modules and Emotion (or CSS-in-JS in general) are not limited to React.

Hooks in React

Hooks are arguably the most anticipated addition to React since its rewrite. Do they live up to the hype? From my experience, absolutely! Hooks are functions that unlock new possibilities, including:

- Reducing the need for

classcomponents solely used for features like local state or refs, leading to cleaner component code. - Achieving the same results with less code.

- Making functions easier to reason about and test (e.g., using the react-testing-library).

- Accepting parameters, with results from one hook usable in another (e.g., using

setStatefromuseStatewithinuseEffect). - Improved minification compared to classes, which can be problematic for minifiers.

- Potentially eliminating the need for HOCs and render props patterns, which can introduce new challenges while solving others.

- Enabling the creation of custom hooks by any skilled React developer.

React includes several built-in hooks. The three fundamental ones are useState, useEffect, and useContext. Additionally, there are several others, such as useRef and useMemo. Let’s focus on the basics for now.

Let’s examine useState by creating a simple counter example. The implementation is straightforward:

| |

It’s invoked with an initialState (value) and returns an array containing two elements. Using array destructuring, we can directly assign these elements to variables. The first element always represents the latest state after updates, while the second is a function used to update the state. Simple, right?

Due to the evolving nature of components previously known as stateless functional components, this naming convention is no longer accurate, as they can now have state using hooks. The terms class components and function components better reflect their functionality, at least since version 16.8.0.

The update function (in our case, setCounter) can also accept a function that receives the previous state as an argument:

| |

However, unlike this.setState in class components, which performs a shallow merge, using a function with setCounter overrides the entire state.

Furthermore, initialState can be a function instead of a plain value. This function is executed only during the initial render and not on subsequent renders.

| |

It’s worth noting that if you call setCounter with the same value as the current state (counter), the component will not re-render.

Next, useEffect allows us to introduce side effects into functional components. This includes subscriptions, API calls, timers, or any other necessary operations. Functions passed to useEffect are executed after every render unless a dependency array is provided as the second argument, specifying which prop changes should trigger a re-run. To execute the effect only on mount and cleanup on unmount, pass an empty array.

| |

The code above will run only once due to the empty dependency array. It behaves similarly to componentDidMount but fires slightly later. If you need a similar hook that runs before the browser paint, use useLayoutEffect, but be aware that updates using this hook are applied synchronously, unlike useEffect.

useContext is relatively straightforward to grasp. You provide the context you want to access (the object returned by createContext), and it returns the corresponding context value.

| |

Creating your own hook is simple:

| |

Here, we utilize the standard useState hook and initialize it with the window width. Then, within useEffect, we attach a listener that triggers handleResize on window resize events. We also clean up the listener when the component unmounts (see the return statement in useEffect). Easy!

Note: The keyword use in hook names is crucial. It enables React to enforce rules and prevent incorrect usage, such as calling hooks from regular JavaScript functions.

Checking Types

Before Flow and TypeScript became prevalent, React had its own prop checking mechanism.

PropTypes verify that the properties (props) received by a React component adhere to the defined structure. If there’s a mismatch (e.g., an object instead of an array), a warning is logged to the console. Keep in mind that PropTypes are only checked in development mode due to their potential performance impact.

Since React 15.5, PropTypes reside in a separate package that needs to be installed. They are declared alongside regular props using a static property called propTypes (unsurprisingly). You can combine them with defaultProps, which provide default values for undefined props. While DefaultProps are not directly related to PropTypes, they can help resolve some PropTypes warnings.

Currently, Flow and TypeScript are far more popular choices for type checking in React projects.

- TypeScript, developed by Microsoft, is a typed superset of JavaScript that catches errors before runtime and offers superior autocomplete during development. It also significantly improves refactoring. With Microsoft’s backing and extensive experience with typed languages, TypeScript is a reliable choice.

- Flow, unlike TypeScript, is not a separate language but a static type checker for JavaScript. It’s more of a tool integrated into JavaScript than a language itself. Flow’s core concept is similar to TypeScript’s, enabling type annotations to reduce bugs before execution. CRA (Create React App) supports both TypeScript and Flow out of the box.

Personally, I find TypeScript to be faster, particularly with autocomplete, which can be a bit sluggish in Flow. It’s worth noting that IDEs like WebStorm, which I prefer, rely on a CLI for Flow integration. On the other hand, Flow offers an easy opt-in mechanism for individual files using the // @flow comment at the beginning. From what I’ve observed, TypeScript seems to have gained more traction than Flow, with many popular libraries being migrated from Flow to TypeScript.

There are other options mentioned in the official React documentation, such as Reason (developed by Facebook and gaining popularity within the React community), Kotlin (developed by JetBrains), and more.

For front-end developers, Flow and TypeScript offer a lower barrier to entry compared to switching to languages like Kotlin or F#. However, for back-end developers transitioning to front-end, these languages might be easier to adopt.

Production and React Performance

The most fundamental change for production is switching the DefinePlugin to “production” mode and adding the UglifyJsPlugin for Webpack. In CRA, this is as simple as running npm run build (which executes react-scripts build). Keep in mind that Webpack and CRA are not the only build tools available; alternatives like Brunch exist. Refer to the official React documentation or the specific tool’s documentation for guidance. To verify the correct mode, use React Developer Tools, which indicates whether you’re in production or development mode. These steps ensure your application runs without development checks and warnings, and the resulting bundle is minified.

For React applications, you can further optimize the handling of the built JavaScript file. If the bundle size is relatively small, you can stick with a single “bundle.js” file. Alternatively, consider splitting it into “vendor + bundle” or “vendor + smallest required part + dynamically import other parts when needed.” This approach is beneficial for large applications where loading everything upfront is unnecessary. Remember that including unused JavaScript code in the main bundle increases its size and slows down initial load times.

Vendor bundles are useful if you plan to freeze library versions that are unlikely to change frequently (or at all). Also, larger files compress better with gzip, so the benefits of splitting might not always outweigh the overhead. Experimentation is key, as the ideal approach depends on your specific file sizes.

Code Splitting

Code splitting can be implemented in various ways, but let’s focus on the approaches available in CRA and React itself. To split code into separate chunks, we can utilize import(), which leverages Webpack’s capabilities (import itself is currently a Stage 3 proposal and not yet part of the JavaScript standard). When Webpack encounters import(), it initiates code splitting, separating the code within the import() statement into a different chunk.

Combining this with React.lazy(), which also requires import(), allows us to dynamically load components. We provide the file path to the component that needs to be rendered. Then, using React.suspense(), we can display a fallback component while the imported component loads. You might wonder why this is necessary if we’re importing a single component.

The reason is that React.lazy() displays the component loaded via import(), but import() might fetch more than just that component. It could include other libraries, additional code, and more, resulting in multiple bundled files. Finally, we can wrap everything in an ErrorBoundary (refer to the error boundaries section for code) to handle potential errors during component import (e.g., network errors).

| |

This is a basic example, and you can achieve much more. You can use import and React.lazy for dynamic route splitting (e.g., separate bundles for admin and regular users or for large routes). However, keep in mind that React.lazy currently only supports default exports and doesn’t work with server-side rendering.

React Code Performance

If your React application experiences performance issues, two tools can help identify the bottlenecks.

The first is Chrome Performance Tab, which provides insights into component lifecycles (e.g., mount, update). This helps pinpoint components causing performance issues and optimize them accordingly.

The other option is the DevTools Profiler](https://reactjs.org/blog/2018/09/10/introducing-the-react-profiler.html), introduced in React 16.5+. Combined with shouldComponentUpdate (or PureComponent, explained in [part one of this tutorial]), it enables performance optimization for critical components.

Of course, following web development best practices is crucial. This includes debouncing events like scrolling, optimizing animations (using transforms instead of animating height changes), and more. It’s easy to overlook these best practices, especially when starting with React.

The State of React in 2019 and Beyond

Regarding the future of React, I remain optimistic. In my view, React will maintain its dominant position in 2019 and beyond.

With a strong foundation, a large and active community, and continuous improvements from the core team, React is well-positioned for the foreseeable future. The community is vibrant, constantly generating new ideas, while the core team remains dedicated to enhancing React, introducing new features, and addressing existing issues. React also benefits from backing by a large company, and the previous licensing concerns have been resolved with the MIT license.

While some areas are expected to evolve or improve (e.g., reducing React’s size by potentially removing synthetic events or renaming className to class), even minor changes can have implications for browser compatibility. It remains to be seen how Web Components will impact React’s role as they gain popularity. While I don’t anticipate Web Components replacing React entirely, they could complement each other well.

In the near term, hooks are a significant addition to React. This is arguably the most substantial change since the rewrite, opening up new opportunities and further empowering functional components.

Finally, there’s React Native, a technology I’ve been extensively involved with. React Native has made significant strides in recent years, addressing issues like the lack of a robust navigation solution and numerous bugs. It’s currently undergoing a core rewrite, which, similar to the React rewrite, aims to be internal without requiring major changes for developers. Exciting improvements include asynchronous rendering, a faster and more efficient bridge between native and JavaScript, and much more.

The React ecosystem has a bright future, with hooks and React Native updates poised to be the most impactful changes in 2019.