As a skilled JavaScript developer, you aim for code that is clear, efficient, and easy to maintain. You tackle fascinating problems that, while distinct, don’t always demand novel solutions. You’ve probably written code resembling the answer to a completely different issue you’ve solved before. Though you might not realize it, you’ve employed JavaScript design patterns. These patterns are reusable solutions to recurring challenges in software development.

Over a language’s existence, numerous such reusable solutions are crafted and evaluated by a multitude of developers within that language’s community. This collective wisdom is what makes these solutions so valuable. They guide us in writing streamlined code while effectively addressing the problem at hand.

Design patterns offer several key advantages:

- Proven Solutions: Due to their widespread use, design patterns have a track record of success. They’ve often undergone multiple revisions and optimizations.

- Easy Reusability: Design patterns provide adaptable solutions that can be tailored to address various specific problems. They’re not confined to a single issue.

- Expressiveness: Design patterns offer elegant explanations for complex solutions.

- Enhanced Communication: When developers share a familiarity with design patterns, they can discuss potential solutions more effectively.

- Reduced Refactoring: Applications designed with patterns in mind often minimize the need for later refactoring, as the right pattern provides an optimal solution from the outset.

- Smaller Codebase: The elegance and efficiency of design patterns often lead to shorter, more concise code compared to alternative approaches.

Before we delve into JavaScript design patterns, let’s review some fundamental concepts.

A Concise History of JavaScript

JavaScript is currently one of the most popular programming languages for web development. Originally conceived as a “glue” to connect various displayed HTML elements, it was known as a client-side scripting language for early web browsers like Netscape Navigator, which could only render static HTML. The concept of such a scripting language sparked browser wars among industry giants like Netscape Communications (now Mozilla), Microsoft, and others.

Each major player sought to establish its own implementation of this scripting language, leading to Netscape’s JavaScript (created by Brendan Eich), Microsoft’s JScript, and so on. These implementations differed significantly, resulting in browser-specific development and “best viewed on” stickers accompanying web pages. The need for a standard, a cross-browser solution to unify development and simplify web page creation, became evident. This led to the emergence of ECMAScript.

ECMAScript is a standardized scripting language specification that all modern browsers strive to support. It boasts multiple implementations (or dialects), with JavaScript being the most prominent, as covered in this article. Since its inception, ECMAScript has standardized numerous crucial aspects. For the detail-oriented, Wikipedia provides a comprehensive list of standardized elements for each ECMAScript version. Browser support for ECMAScript versions 6 (ES6) and above remains incomplete, requiring transpilation to ES5 for full compatibility.

Understanding JavaScript

To fully grasp this article’s content, let’s introduce some vital language characteristics essential for comprehending JavaScript patterns. If asked “What is JavaScript?”, you might respond along these lines:

JavaScript is a lightweight, interpreted, object-oriented programming language with first-class functions, widely recognized as a scripting language for web pages.

This definition implies that JavaScript code has minimal memory usage, is easy to implement and learn, and boasts a syntax akin to languages like C++ and Java. As an interpreted language, its code is executed without prior compilation. Its support for procedural, object-oriented, and functional programming styles provides developers with remarkable flexibility.

While these features might seem common to many languages, let’s explore what distinguishes JavaScript. I’ll highlight a few key characteristics and elaborate on their significance.

First-class Functions in JavaScript

Coming from a C/C++ background, I initially struggled with this concept. JavaScript treats functions as first-class citizens, allowing you to pass them as arguments to other functions just like any other variable.

| |

JavaScript’s Prototype-based Nature

Similar to many object-oriented languages, JavaScript supports objects. Classes and inheritance are often associated with objects. However, JavaScript deviates slightly by not directly supporting classes in its core syntax. Instead, it employs prototype-based or instance-based inheritance.

ES6 introduces the formal term “class,” but browsers still lack full support. Even with the introduction of “class,” JavaScript continues to utilize prototype-based inheritance behind the scenes.

Prototype-based programming is an object-oriented style where behavior reuse (inheritance) involves reusing existing objects through delegation, with these objects serving as prototypes. We’ll delve deeper into this concept in the design patterns section, as many JS design patterns utilize this characteristic.

JavaScript Event Loops

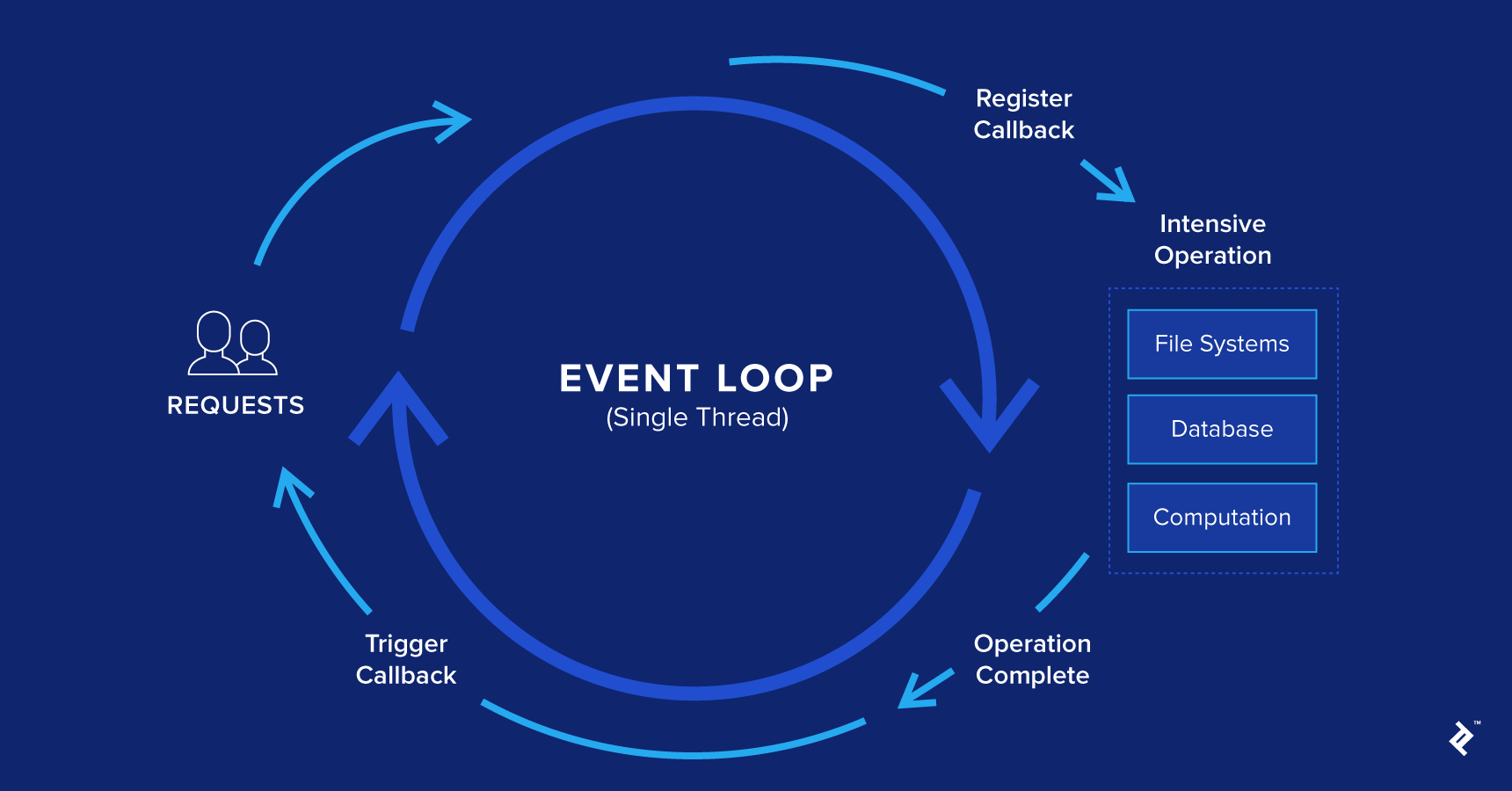

If you’ve worked with JavaScript, you’re likely familiar with “callback functions.” For the uninitiated, a callback function, passed as a parameter to another function (remembering that JavaScript treats functions as first-class citizens), executes after an event occurs. This mechanism is commonly used for subscribing to events like mouse clicks or key presses.

Whenever an event with an attached listener is triggered (otherwise, the event is lost), a message is sent to a queue, processed synchronously in a FIFO (first-in-first-out) manner. This is known as the event loop.

Each queued message has an associated function. When a message is dequeued, the runtime fully executes the function before processing any other message. Even if a function contains other function calls, they are all completed before handling the next queued message. This is called run-to-completion.

| |

The queue.waitForMessage() synchronously awaits new messages. Each message being processed has its own stack, which is processed until empty. Upon completion, a new message from the queue is processed, if available.

You may have heard that JavaScript is non-blocking. This means that during asynchronous operations, the program can handle other tasks, like user input, without halting the main execution thread while awaiting the asynchronous operation’s completion. This valuable JavaScript feature deserves its own article, but it falls outside this article’s scope.

Demystifying Design Patterns in JavaScript

As previously mentioned, design patterns are reusable solutions to common software design problems. Let’s explore some design pattern categories.

Proto-patterns: The Budding Stage

How does a pattern come to be? Imagine identifying a recurring problem and devising your own unique, undocumented solution. You consistently apply this solution, believing it’s reusable and beneficial to the developer community.

Does it instantly become a pattern? Fortunately, no. Developers with solid coding practices might mistake something resembling a pattern for an actual one.

So, how can you determine if what you’ve recognized is a genuine design pattern?

It involves seeking feedback from fellow developers, understanding the pattern creation process, and familiarizing yourself with existing patterns. A pattern must undergo a testing phase before achieving full-fledged status. This stage is called a proto-pattern.

A proto-pattern represents a potential pattern if it withstands rigorous testing by various developers across diverse scenarios, demonstrating its utility and accuracy. Transitioning to a fully recognized pattern involves substantial effort and documentation, exceeding the scope of this article.

Anti-patterns: Practices to Avoid

While design patterns embody good practices, anti-patterns represent the opposite—practices to steer clear of.

Modifying the Object class prototype is a prime example of an anti-pattern. Nearly all JavaScript objects inherit from Object (due to JavaScript’s prototype-based inheritance). Altering this prototype would affect all inheriting objects—a vast majority of JavaScript objects. This is a recipe for disaster.

Similarly, modifying objects you don’t own, like overriding a function from an object used extensively throughout an application, is another anti-pattern. In a large team setting, this could lead to naming conflicts, incompatible implementations, and maintenance nightmares.

Just as understanding good practices and solutions is crucial, so is recognizing and avoiding bad ones.

Categorizing Design Patterns

Design patterns can be categorized in various ways, with the most common being:

- Creational design patterns

- Structural design patterns

- Behavioral design patterns

- Concurrency design patterns

- Architectural design patterns

Creational Design Patterns

These patterns focus on object creation mechanisms that optimize the process compared to basic approaches. The fundamental way of creating objects can lead to design flaws or increased complexity. Creational patterns address this by controlling object creation. Popular patterns in this category include:

- Factory method

- Abstract factory

- Builder

- Prototype

- Singleton

Structural Design Patterns

These patterns concern object relationships, ensuring that changes to one part of a system don’t necessitate modifications throughout the entire system. Common patterns in this category include:

- Adapter

- Bridge

- Composite

- Decorator

- Facade

- Flyweight

- Proxy

Behavioral Design Patterns

Behavioral patterns focus on recognizing, implementing, and enhancing communication between different objects within a system. They help maintain synchronization among disparate system components. Well-known examples include:

- Chain of responsibility

- Command

- Iterator

- Mediator

- Memento

- Observer

- State

- Strategy

- Visitor

Concurrency Design Patterns

These patterns address multi-threaded programming paradigms. Some popular ones are:

- Active object

- Nuclear reaction

- Scheduler

Architectural Design Patterns

As the name suggests, these patterns are employed for architectural purposes. Some of the most renowned ones include:

- MVC (Model-View-Controller)

- MVP (Model-View-Presenter)

- MVVM (Model-View-ViewModel)

In the next section, we’ll delve into some of these design patterns with illustrative examples for better comprehension.

Illustrating Design Patterns with Examples

Each design pattern offers a specific solution to a particular problem. There’s no one-size-fits-all set of patterns. It’s vital to understand when a pattern is beneficial and whether it adds value. Familiarity with patterns and their ideal use cases enables us to determine their suitability for a given problem.

Applying the wrong pattern can have detrimental effects, leading to unnecessary code complexity, performance overhead, or even new anti-patterns.

These are critical considerations when applying design patterns. Let’s explore some JS design patterns every senior JavaScript developer should know.

Constructor Pattern

In classical object-oriented languages, a constructor is a special function within a class that initializes an object with default and/or provided values.

Common methods for creating objects in JavaScript include:

| |

Once an object is created, there are four ways (since ES3) to add properties:

| |

Curly brackets are the most popular method for object creation, while dot notation or square brackets are commonly used for adding properties. These are familiar tools for anyone with JavaScript experience.

While JavaScript lacks native class support, it allows for constructors using the “new” keyword before a function call. This enables us to use the function as a constructor and initialize properties like in classical languages.

| |

However, there’s room for improvement. Recall that JavaScript employs prototype-based inheritance. The previous approach redefines the writesCode method for each instance of the Person constructor. To avoid this, we can assign the method to the function prototype:

| |

Now, both Person constructor instances can access a shared instance of the writesCode() method.

Module Pattern

JavaScript never fails to surprise. Unlike many object-oriented languages, JavaScript doesn’t support access modifiers. In classical OOP, developers define classes and specify access rights for their members. Since JavaScript lacks native support for both classes and access modifiers, developers devised a way to emulate this behavior when needed.

Before exploring the module pattern, let’s discuss closures. A closure is a function that retains access to its parent scope even after the parent function completes execution. Closures help mimic access modifiers through scoping. Here’s an example:

| |

The IIFE ties the counter variable to a function that has been invoked and closed. However, the child function, which increments the counter, can still access it. Since the counter variable is inaccessible from outside the function expression, we’ve achieved privacy through scope manipulation.

Closures enable us to create objects with private and public components, known as modules. These are invaluable when we need to conceal specific object parts and expose only a necessary interface to the module’s user. Consider this example:

| |

This pattern’s key advantage is the clear separation of private and public object aspects, resonating with developers from classical object-oriented backgrounds.

However, there are drawbacks. Changing a member’s visibility requires code modification wherever that member is used due to the different access methods for public and private parts. Additionally, methods added after object creation cannot access the object’s private members.

Revealing Module Pattern

This pattern improves upon the module pattern described above. The primary distinction is that all object logic is written within the module’s private scope, with desired public parts exposed by returning an anonymous object. We can also rename private members when mapping them to their public counterparts.

| |

The revealing module pattern is one of at least three ways to implement a module pattern. The main differences lie in how public members are referenced. This makes the revealing module pattern easier to use and modify. However, it can be fragile in scenarios like using RMP objects as prototypes in inheritance chains. The problematic situations are:

- Private functions referencing public functions prevent overriding the public function, as the private function continues referencing the private implementation, introducing a bug.

- Public members pointing to private variables, when overridden externally, can lead to other functions still referencing the private value, causing issues.

Singleton Pattern

The singleton pattern is employed when a single instance of a class is required. For instance, you might need an object storing configuration settings. Creating a new object each time this configuration is needed throughout the system is unnecessary.

| |

In this example, the generated random number and config values remain constant because they are tied to the single instance.

It’s crucial that the access point for retrieving the singleton instance is unique and well-defined. Testing can be challenging with this pattern.

Observer Pattern

The observer pattern is highly effective for optimizing communication between disparate system components, promoting loose coupling.

While variations exist, this pattern generally involves two primary components: subjects and observers.

A subject manages operations related to a specific topic that observers subscribe to. These operations include subscribing and unsubscribing observers from topics and notifying them about events related to those topics.

A variant, the publisher/subscriber pattern, will be illustrated here. The key difference is that publisher/subscriber promotes even looser coupling.

While the observer pattern’s subject holds references to subscribed observers, directly calling their methods, the publisher/subscriber pattern utilizes channels as communication bridges between subscribers and publishers. The publisher triggers an event and executes the associated callback function.

A short publisher/subscriber example is provided below. For those interested, classic observer pattern examples are readily available online.

| |

This pattern is beneficial when multiple operations need to be performed based on a single event. Imagine making multiple AJAX calls to a backend service, with subsequent calls dependent on the results. Nesting these calls could lead to “callback hell.” The publisher/subscriber pattern offers a more elegant solution.

Testing various system components can be tricky with this pattern, as there’s no easy way to verify the behavior of subscribing components.

Mediator Pattern

Let’s touch upon a pattern valuable for decoupled systems. When numerous system components require coordination and communication, introducing a mediator can be an effective solution.

A mediator, acting as a central communication hub, handles the workflow between disparate system parts. The emphasis on “workflow” is crucial.

You might wonder: Both this pattern and the publisher/subscriber enhance communication between objects. What sets them apart?

The distinction lies in the mediator’s workflow management. The publisher/subscriber employs a “fire and forget” approach. As an event aggregator, it triggers events and notifies relevant subscribers, unconcerned with post-event actions. The mediator, in contrast, plays an active role in managing the workflow.

A wizard-like interface exemplifies a mediator. Imagine a lengthy registration process for a system. Breaking it down into multiple steps is often a good practice when extensive user information is required.

This approach leads to cleaner, maintainable code, and prevents overwhelming users with information. The mediator, in this case, would handle the registration steps, accommodating potential workflow variations, as each user might have a unique registration path.

This pattern fosters improved communication between system components, now channeled through the mediator, resulting in a cleaner codebase.

However, it introduces a single point of failure. If the mediator fails, the entire system could be compromised.

Prototype Pattern

As mentioned earlier, JavaScript doesn’t inherently support classes. Inheritance between objects is achieved through prototype-based programming.

This approach allows us to create objects that serve as prototypes for new objects. The prototype acts as a blueprint.

Having touched upon this concept, let’s illustrate its use with a simple example.

| |

Notice how prototype inheritance enhances performance. Both objects reference functions implemented within the prototype itself, rather than duplicating them within each object.

Command Pattern

The command pattern is valuable for decoupling objects that execute commands from those issuing them. Consider an application heavily reliant on API calls. If these APIs change, you’d need to modify the code wherever the affected APIs are called.

This scenario calls for an abstraction layer to separate objects making API calls from those dictating when to make them. This eliminates the need to modify every instance where the service is invoked. Instead, only the objects making the call—a single location—require changes.

As with any pattern, it’s crucial to recognize when it’s truly necessary. We must weigh the tradeoffs. Adding an abstraction layer over API calls can impact performance but potentially save substantial time during modifications.

| |

Facade Pattern

The facade pattern creates an abstraction layer between the public interface and the underlying implementation. It’s useful when a simpler or more user-friendly interface to a complex object is desired.

Selectors from DOM manipulation libraries like jQuery, Dojo, or D3 exemplify this pattern. These libraries boast powerful selector features, enabling complex queries like:

| |

This simplification hides the intricate logic operating behind the scenes.

The performance-simplicity tradeoff should always be considered. Avoid unnecessary complexity unless the benefits outweigh the drawbacks. In the case of these libraries, the tradeoff proved worthwhile, contributing to their success.

Moving Forward

Design patterns are indispensable tools for senior JavaScript developers. Understanding their intricacies can prove invaluable, saving time throughout a project’s lifecycle, particularly during maintenance. Modifying and maintaining systems built with appropriate design patterns can be immensely beneficial.

To maintain brevity, we’ll conclude the examples here. For further exploration, I highly recommend two sources that inspired this article: the Gang of Four’s book Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software and Addy Osmani’s Learning JavaScript Design Patterns.