The Swift programming language derives significant power from its protocol feature.

Protocols establish a “blueprint” outlining the methods, properties, and other specifications necessary for specific tasks or functionalities.

Swift’s compile-time protocol conformity checks enable developers to catch critical code errors before execution. This protocol system allows for flexible and extensible code without sacrificing Swift’s inherent expressiveness.

Swift elevates the practicality of protocols by offering solutions to common interface limitations found in many other programming languages.

While previous Swift versions only permitted extensions for classes, structures, and enums (common in modern languages), version 2 onwards allows protocol extensions as well.

This article explores how Swift protocols facilitate reusable, maintainable code, and how protocol extensions help consolidate changes within large, protocol-oriented codebases.

Protocols

So, what exactly is a protocol?

In essence, a protocol acts as an interface that defines properties and methods. Any type conforming to a protocol must provide specific values for the defined properties and implement the required methods. To illustrate:

| |

The Queue protocol describes a queue containing integer items using straightforward syntax.

When defining a property within the protocol block, it’s necessary to specify whether it’s read-only ({ get }) or both readable and writable ({ get set }). Here, the Count variable (an Int) is read-only.

If a protocol requires a property to be both gettable and settable, a constant stored property or a read-only computed property won’t suffice.

However, if only gettability is required, any property type can fulfill the requirement, and the property can still be settable if it benefits your code.

For functions defined within a protocol, the mutating keyword is crucial for indicating whether the function modifies content. Apart from this, the function signature acts as a sufficient definition.

To conform to a protocol, a type must furnish all instance properties and implement all methods outlined in the protocol. As an example, below is the Container struct, conforming to our Queue protocol by storing pushed Ints within a private items array.

| |

However, our current Queue protocol has a significant drawback.

Only containers handling Ints can conform to it.

This limitation can be overcome using “associated types,” which function similarly to generics. Let’s modify the Queue protocol to demonstrate this:

| |

Now, the Queue protocol allows storing any type of item.

When implementing the Container structure, the compiler infers the associated type from the context (method return type and parameter types). This allows creating a Container structure with a generic items type, as shown below:

| |

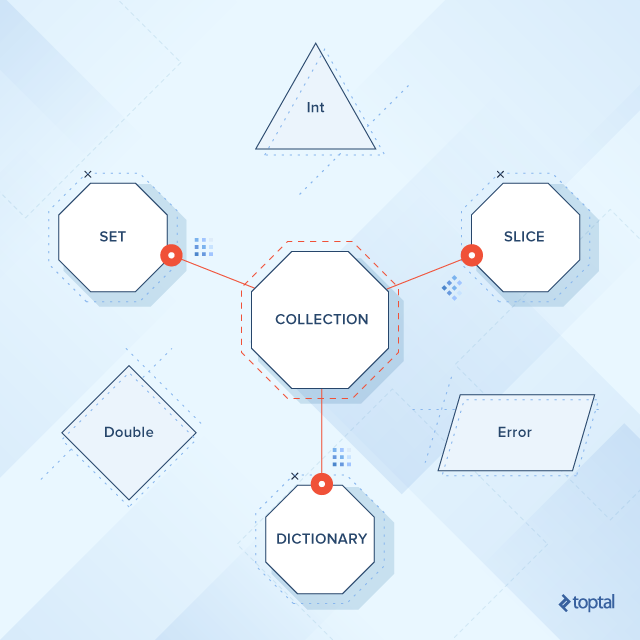

Protocols simplify coding in many scenarios.

For instance, any object representing an error can conform to the Error protocol (or LocalizedError for localized descriptions).

This allows for applying the same error handling logic to any of these error objects throughout your code, eliminating the need for a specific object (like Objective-C’s NSError) to represent errors. You can use any type conforming to Error or LocalizedError.

You can even extend the String type to conform to LocalizedError and throw strings as errors.

| |

Protocol Extensions

Protocol extensions enhance protocols by enabling us to:

Provide default implementations for protocol methods and default values for properties, making them “optional.” Conforming types can choose between providing their own implementations or utilizing the defaults.

Add implementations for methods not explicitly defined in the protocol, “decorating” conforming types with these additional methods. This allows adding specific methods to multiple types already conforming to the protocol without individually modifying each type.

Default Method Implementation

Let’s define another protocol:

| |

This protocol defines objects responsible for handling application errors. For example:

| |

Here, we simply print the error’s localized description. Protocol extensions allow us to make this the default implementation.

| |

This makes the handle method optional by providing a default implementation.

This ability to extend existing protocols with default behaviors is powerful, allowing protocols to evolve and expand without breaking compatibility with existing code.

Conditional Extensions

While we provided a default handle method implementation, simply printing to the console isn’t very user-friendly.

Ideally, we’d present an alert view with a localized description when the error handler is a view controller. We can achieve this by extending the ErrorHandler protocol but limit the extension to specific cases (when the type is a view controller).

Swift allows adding such conditions to protocol extensions using the where keyword.

| |

Self (capital “S”) here refers to the type (structure, class, or enum). By specifying that we’re extending the protocol only for types inheriting from UIViewController, we gain access to UIViewController specific methods (like present(viewControllerToPresnt: animated: completion)).

Now, any view controller conforming to ErrorHandler has its own default handle method implementation that displays an alert view with a localized description.

Ambiguous Method Implementations

Consider two protocols, each with a method having the same signature:

| |

Both protocols have extensions providing default implementations for their respective methods.

| |

Now, suppose a type conforms to both protocols:

| |

This leads to an ambiguous method implementation issue. The type doesn’t clearly indicate which implementation to use, resulting in a compilation error. To resolve this, we must explicitly implement the method within the type itself.

| |

Many object-oriented languages struggle with resolving ambiguous extension definitions. Swift handles this gracefully through protocol extensions by empowering the programmer to address situations where the compiler falls short.

Adding New Methods

Let’s revisit the Queue protocol:

| |

Every type conforming to Queue has a count instance property indicating the number of stored items. This allows us, for instance, to compare these types to determine which is larger. We can add this comparison method via protocol extension:

| |

This method isn’t part of the Queue protocol itself because it’s not directly related to queue functionality.

Therefore, it’s not a default protocol method implementation but rather a new method implementation “decorating” all conforming types. Without protocol extensions, we’d need to add this method to each type individually.

Protocol Extensions vs. Base Classes

While seemingly similar to using a base class, protocol extensions offer distinct advantages:

Classes, structures, and enums can conform to multiple protocols, inheriting default implementations from all of them. This resembles multiple inheritance in other languages.

Protocols are adoptable by classes, structures, and enums, while base classes and inheritance are limited to classes.

Swift Standard Library Extensions

Besides extending custom protocols, you can extend those from Swift’s standard library. For example, to find the average size of a collection of queues, we can extend the standard Collection protocol.

Sequence data structures in Swift’s standard library, where elements are traversable and accessible via indexed subscripts, usually conform to the Collection protocol. Protocol extensions allow extending all such data structures or selectively extending a subset.

Note: The protocol previously known as

CollectionTypein Swift 2.x was renamed toCollectionin Swift 3.

| |

Now we can calculate the average size of any queue collection (Array, Set, etc.). Without protocol extensions, we’d have to add this method to each collection type separately.

Swift’s standard library utilizes protocol extensions for implementing methods like map, filter, reduce, and others.

| |

Protocol Extensions and Polymorphism

As mentioned earlier, protocol extensions allow adding default method implementations and entirely new ones. But what distinguishes these two features? Let’s return to the error handler example.

| |

This results in a fatal error.

Now, remove the handle(error: Error) method declaration from the protocol.

| |

The outcome remains the same: a fatal error.

Does this imply no difference between adding a default protocol method implementation and adding a new one via extension?

Not quite! A difference exists, evident when changing the handler variable type from Handler to ErrorHandler.

| |

Now, the console output is: The operation couldn’t be completed. (ApplicationError error 0.)

However, reintroducing the handle(error: Error) method declaration to the protocol reverts to the fatal error.

| |

Let’s analyze the order of events in each scenario.

Method declaration present in the protocol:

The protocol declares the handle(error: Error) method and provides a default implementation. The Handler implementation overrides this method. Consequently, the correct implementation is invoked at runtime, regardless of the variable’s type.

Method declaration absent from the protocol:

Without the method declaration in the protocol, the type cannot override it. Thus, the invoked implementation depends on the variable’s type.

If it’s of type Handler, the implementation within the type is called. If it’s ErrorHandler, the implementation from the protocol extension is invoked.

Protocol-oriented Code: Safe yet Expressive

This article showcased the power of protocol extensions in Swift.

Unlike other languages with restrictive interfaces, Swift’s protocols are more flexible. Swift circumvents common limitations by allowing developers to resolve ambiguities as needed.

Swift protocols and their extensions enable code to be as expressive as in dynamic languages while retaining compile-time type safety. This ensures code reusability, maintainability, and increases confidence when making changes to your Swift codebase.

We hope this article proves beneficial and welcome your feedback and insights.