Coding isn’t always about practical tasks like app development, goal achievement, or meeting project requirements. It can be a source of enjoyment, a way to revel in the creation process. In fact, many individuals see programming and its development as a recreational activity. At Toptal, we were eager to experiment with something novel within our community. Thus, we decided to develop a bot-vs-bot gaming platform centered around Battleship, which is now open-source.

Since its internal launch, the platform has attracted considerable interest from talented bot creators in our community. We were particularly impressed by Toptal engineer Quân Lê, who developed a tool for effortless debugging of Battlescripts bots. The announcement also sparked interest in building custom bot-vs-bot engines, supporting diverse game types and rules. From the unveiling of Battlescripts, innovative ideas have poured in. Today, we’re pleased to announce that Battlescripts is open-source. This allows our community and others to explore the codebase, contribute, or fork it to create something entirely new.

A Look Inside Battlescripts

Battlescripts is constructed using straightforward components. It operates on Node.js and utilizes popular, well-implemented packages like Express, Mongoose, and more. Both the back-end and front-end scripts are written in pure JavaScript. The application only relies on two external dependencies: MongoDB and Redis. User-submitted bot code is executed using the “vm” module module included in Node.js. While Docker enhances security in production, it is not a mandatory requirement for running Battlescripts.

The Battlescripts code is available on GitHub under the BSD 3-clause license. The included README.md provides comprehensive instructions on cloning the repository and running the application locally.

Web Server

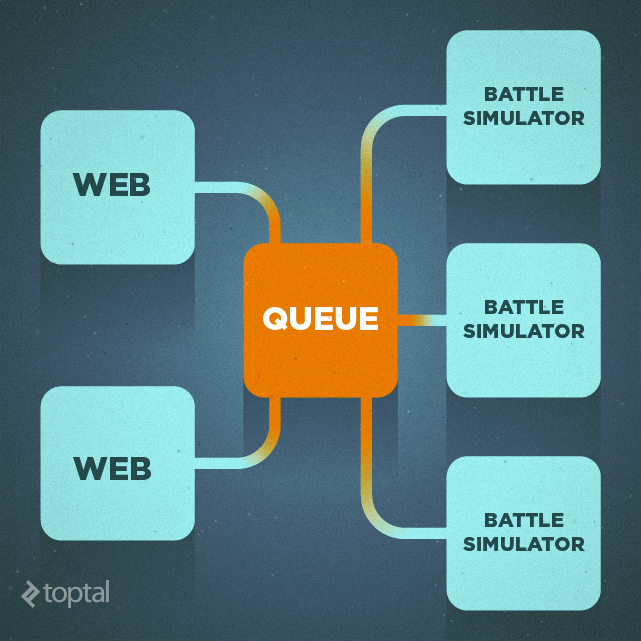

The application’s structure resembles that of simple Express.js web applications. The app.js file initializes the server, connecting to the database, registering common middleware, and defining social authentication strategies. Models and routes are defined within the “lib/” directory. The application requires only a few models: Battle, Bot, Challenge, Contest, Party, and User. Bot battles are simulated externally using the Node.js package Kue. This isolation of the engine from the web server nodes prevents interference and maintains web application responsiveness and stability.

Bots & Engine

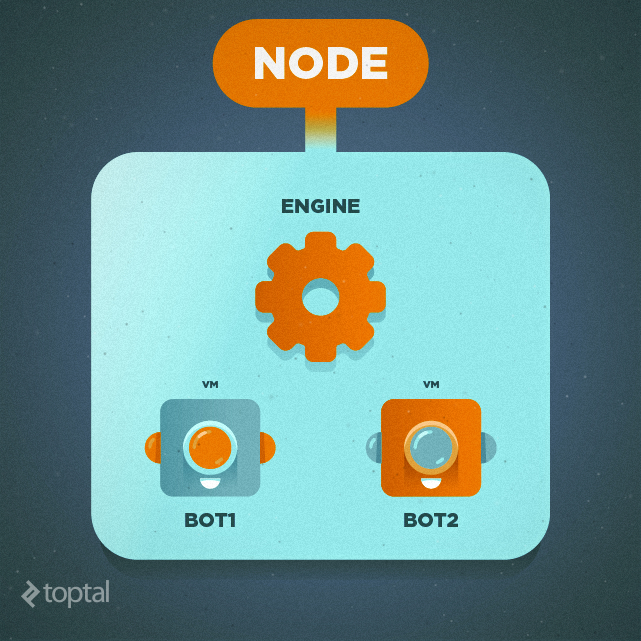

Building the engine was simplified by the fact that bots are written in JavaScript, the same language used for our Node.js back-end. When handling user-submitted code, ensuring it doesn’t compromise server security or stability is paramount. Node.js provides the “vm” module, which addresses part of this challenge by enabling the execution of untrusted code in an isolated context. While the official documentation recommends running untrusted code in a separate process for production environments, the “vm” module and its features suffice for local development.

Executing JavaScript Code

To execute arbitrary JavaScript code within a separate context in Node.js, you can use the “vm” module as follows:

| |

Within this “new context,” the executed code lacks access to functions like “console.log,” as they don’t exist in that environment. However, you can expose functions from the original context, like “context.log,” by passing them as attributes of “ctxObj.”

In Battlescripts, worker nodes simulate battles by running each bot within separate Node.js “vm” contexts. The engine synchronizes the state of these contexts for both bots, adhering to the game’s rules.

The “runInNewContext” function also accepts an optional third argument, an object controlling aspects of code execution:

- The filename used in generated stack traces for this execution.

- Whether errors are printed to stderr.

- The maximum execution time in milliseconds before a timeout occurs.

One limitation of the “vm” module is the inability to restrict memory usage. This and other limitations are addressed on the production server using Docker and by how engine nodes are managed. Frequent use of the “vm” module can lead to memory leaks that are hard to trace and resolve. Even reusing context objects doesn’t prevent this memory growth. Our solution involves a simple strategy: after each battle simulation in a worker node, the node terminates. A supervisor program on the production server then immediately restarts the worker node, making it available for the next simulation within a fraction of a second.

Enhancing Extensibility

Initially, Battlescripts was designed around the standard rules of Battleship, with a less extensible engine. However, requests for new game types emerged, as users realized some games are easier for bots to master. For instance, TicTacToe has a smaller state space than Chess, making it simpler for bots to achieve a win or draw.

Recent modifications to the Battlescripts engine simplify the introduction of new game types. This is achieved by adhering to a structure with a few hook-like functions. To illustrate, TicTacToe was added as a new game type, with all related code residing in “lib/games/tictactoe.js.”

For this article, we’ll focus on the Battleship implementation. Exploring the TicTacToe code is left as an exercise.

Battleship Game Logic

Before examining the game’s implementation, let’s glance at a standard Battlescript bot:

| |

That’s it! Each bot is a constructor function with a “play” method. This method is called each turn, receiving an object as an argument. This object contains a method for the bot to make its move and may include additional attributes reflecting the game state.

As mentioned, the engine has been refactored. Battleship-specific logic is extracted from the core engine. While the engine handles the complexities, the Battleship game definition remains simple:

| |

Here, we define three hook functions: init, play, and turn. Each is invoked with the engine as its context. The “init” function is called during engine object instantiation, typically used to initialize engine state attributes. One such attribute, essential for every game, is “grids,” optionally accompanied by “pieces.” This attribute is always an array with two elements, representing the game board state for each player.

| |

The “play” hook is invoked before the game starts, allowing for tasks like placing game pieces on the board for bots.

| |

While this code might appear complex, its purpose is straightforward. It generates arrays of pieces for each bot and positions them uniformly on the corresponding grids. The code scans the grid for each piece, storing valid positions (where pieces don’t overlap or occupy adjacent cells) in a temporary array.

Lastly, the “turn” hook differs slightly from the others. It returns an object used as the first argument when calling a bot’s “play” method.

| |

This method first informs the engine that the bot has made a move. Any bot failing to make an attacking move in any turn automatically forfeits. If the move hits a ship, the code determines if it’s destroyed. If so, it returns details about the destroyed ship; otherwise, it returns “true,” indicating a hit without additional information.

Throughout the code, we see attributes and methods accessed via “this.” These are provided by the Engine object:

this.turn.called: Initially false before each turn, set to true to indicate the bot has acted.

this.turn.botNo: Indicates the bot that made the turn (0 or 1).

this.end(botNo): Ends the game, marking the specified bot as the winner. Calling with -1 results in a draw.

this.track(botNo, isOkay, data, failReason): A convenience method for recording bot move details or failure reasons, used for visualizing the simulation on the front-end.

This essentially covers the back-end implementation of a game on the platform.

Game Replay Functionality

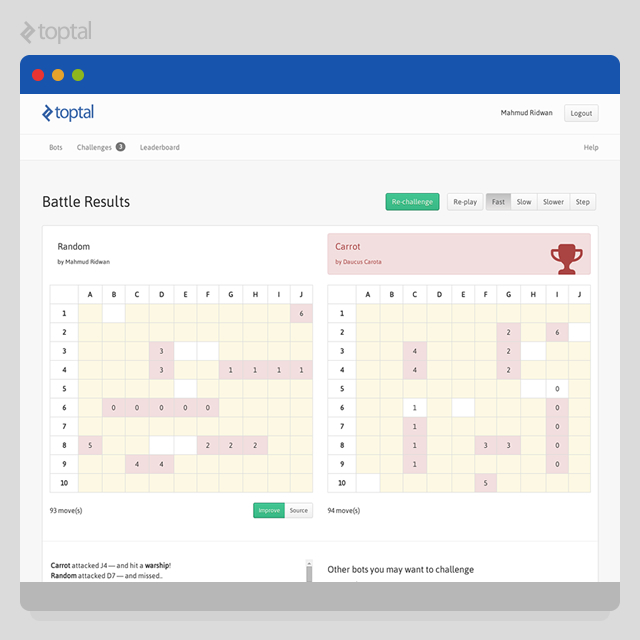

Upon completion of a battle simulation, the front-end redirects to the game replay page, displaying the simulation, results, and game data.

This view is rendered by the back-end using “battle-view-battleships.jade” in the “views/” directory, with battle details in context. The front-end JavaScript handles the replay animation using data recorded by the engine’s “trace()” method, available within this template’s context.

| |

Future Directions

With Battlescripts now open source, contributions are highly encouraged. The platform is mature yet has room for improvement. Whether it’s a new feature, security patch, or bug fix, feel free to open an issue in the repository or fork and submit a pull request. If this inspires you to build something entirely new, let us know and share a link in the comments below!