Is your website’s rendering performance up to par with current standards? Rendering is the process of transforming a server’s response into the visual content displayed by the browser when someone visits your website. A subpar rendering performance can result in a higher bounce rate.

Several server responses determine how a page is rendered. This article focuses on the initial rendering of a web page, which begins with parsing HTML, assuming the browser successfully received HTML as the server’s response. We’ll explore the factors contributing to lengthy rendering times and how to address them.

Critical Rendering Path

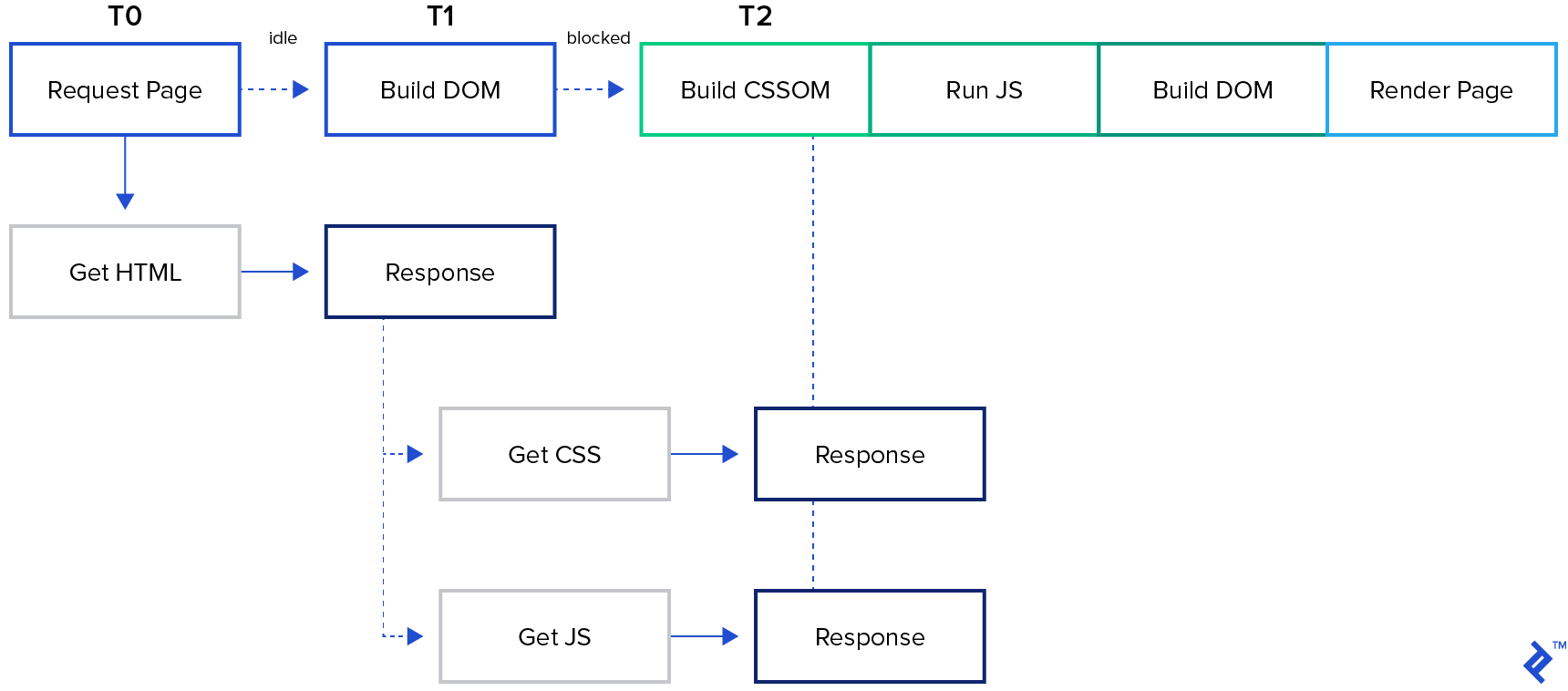

The critical rendering path (CRP) describes the steps your browser takes to convert code into viewable pixels on your screen. While some stages can be performed concurrently to optimize time, others must be executed sequentially. Here’s a visualization:

Initially, the browser receives and begins parsing the server response. Upon encountering a dependency, the browser attempts to download it.

If the dependency is a stylesheet, the browser must fully parse it before rendering the page. This is why CSS is considered render-blocking.

If it’s a script, the browser pauses parsing, downloads the script, and executes it. Only then can parsing resume because JavaScript can modify the web page content, particularly HTML. This is why JS is called parser blocking.

Once parsing is complete, the browser constructs the Document Object Model (DOM) and Cascading Style Sheets Object Model (CSSOM). Combining these models produces the Render Tree. Parts of the page not visible on screen are excluded from the Render Tree, which only includes data essential for drawing the page.

The penultimate stage, Layout (also known as Reflow), translates the Render Tree. Here, the browser calculates the position and size of every Render Tree node.

Finally, the Paint stage involves coloring the pixels based on the data calculated in the previous stages.

Optimization-related Conclusions

Website performance optimization aims to reduce:

- The volume of data transferred.

- The number of resources, especially blocking ones, downloaded by the browser.

- The length of the CRP.

Before delving into the specifics, let’s highlight a crucial optimization principle.

How To Measure Performance

A fundamental rule of optimization: Measure first, optimize as needed. Most browsers’ developer tools include a Performance tab for measuring performance. When optimizing for the fastest initial render, focus on the timing of these events:

- First Paint

- First Contentful Paint

- First Meaningful Paint

“Paint” signifies the successful rendering of a page—the final step in the critical rendering path. Multiple renders may occur consecutively as browsers strive to display content promptly and update it later.

Besides rendering time, consider the number of blocking resources and their download duration. You can find this information in the Performance tab after taking measurements.

Performance Optimization Strategies

Based on our discussion, three primary website performance optimization strategies emerge:

- Minimizing the amount of data transmitted.

- Reducing the total number of critical resources transmitted.

- Shortening the critical rendering path.

1. Minimize the Amount of Data To Be Transferred

Start by removing any unused elements, including unreachable JavaScript functions, styles with selectors that don’t match any element, and HTML tags permanently hidden by CSS. Next, eliminate all duplicates.

Implementing an automated minification process is recommended. For instance, this process should remove comments from server-side output (excluding source code) and unnecessary characters like whitespace in JS.

The remaining content, essentially text, can be safely compressed using an algorithm like GZIP, which most browsers support.

Lastly, caching, while not helpful for the initial render, significantly improves performance on subsequent visits. Two key points to remember:

- Ensure your CDN supports and has properly configured caching.

- Instead of waiting for resource expiration, implement a mechanism to update resources from your end proactively. Embed file “fingerprints” into URLs to enable invalidate local cache.

Define caching policies on a per-resource basis. Some resources rarely change, others are more dynamic, some contain sensitive information, and others are public. Utilize the “private” directive to prevent CDNs from caching private data.

While image requests don’t block parsing or rendering, optimizing web images can also be beneficial.

2. Reduce the Total Count of Critical Resources

“Critical” resources are essential for proper web page rendering. Consequently, we can defer loading styles and scripts not directly involved in this process.

Stylesheets

Indicate non-essential CSS files by setting media attributes to all links referencing stylesheets. This allows the browser to prioritize resources matching the current media (device type, screen size) and treat other stylesheets with lower priority (processed but not as part of the critical rendering path). For instance, adding media="print" to a style tag referencing print styles prevents them from impacting the critical rendering path when the media isn’t print (e.g., when viewing the page in a browser).

Further optimization can be achieved by inlining some styles, reducing the number of server roundtrips otherwise required to fetch stylesheets.

Scripts

Since scripts can modify the DOM and CSSOM, they are parser blocking. However, scripts that don’t alter these structures shouldn’t block parsing, saving valuable time.

Mark all script tags with either the async or defer attribute.

Scripts marked async don’t impede DOM construction or CSSOM as they can execute before CSSOM is ready. Be aware that inline scripts still block CSSOM unless placed before CSS.

Conversely, scripts with the defer attribute are evaluated after the page load. Therefore, they shouldn’t modify the document to avoid triggering a re-render.

In essence, defer delays script execution until after the page load event, while async allows scripts to run in the background during document parsing.

3. Shorten the Critical Rendering Path Length

Strive to minimize the CRP length. The approaches discussed earlier contribute to this goal.

Using media queries as attributes for style tags reduces the number of resources downloaded. The defer and async attributes for script tags prevent scripts from blocking parsing.

Minification, compression, and GZIP archiving shrink the transferred data size, reducing data transfer time.

Inlining styles and scripts minimizes browser-server roundtrips.

Another option is rearranging code within files. For optimal performance, prioritize displaying ATF (above the fold) content—the area immediately visible without scrolling. Restructure code related to ATF rendering to load required styles and scripts first, pausing everything else (parsing and rendering). Always measure performance before and after making changes.

Conclusion: Optimization Encompasses Your Entire Stack

In conclusion, website performance optimization involves all aspects of your site response, including caching, CDN setup, refactoring, resource optimization, and more. However, approach these optimizations incrementally. Use this article as a guide and consistently measure performance before and after implementing changes.

Browser developers continuously work on optimizing website performance. One common technique is the “pre-loader,” which scans ahead in HTML to initiate multiple resource requests simultaneously for parallel processing. Therefore, keeping style and script tags close together in HTML (line-wise) is beneficial.

Additionally, batch HTML updates to minimize layout events triggered not only by DOM or CSSOM changes but also by device orientation shifts and window resizing.

Useful resources and further reading:

- PageSpeed Insights

- Acing Google’s PageSpeed Insights Assessment

- Caching Checklist

- A way to test if GZIP is enabled for your website

- High Performance Browser Networking: A book by Ilya Grigorik