HTTP/3 is the next generation of the HTTP protocol, coming soon after HTTP/2, which is still relatively new. Considering the 16-year gap between HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2, is HTTP/3 really something to be concerned about?

In short, yes, it’s important to stay informed about HTTP/3. Just like HTTP/2 brought significant improvements by switching from ASCII to binary, HTTP/3 introduces major changes by moving from TCP to UDP as the underlying transport protocol.

Despite being in its draft stage, HTTP/3 is already being implemented, and there’s a good chance it’s running on your network. However, its functionality presents new challenges. What are the advantages? What do network engineers, system administrators, and developers need to know?

TL;DR

- Faster websites are more successful.

- HTTP/2 brings a big performance boost because it solves the HTTP head-of-line blocking problem (HOL). It introduces request/response multiplexing, binary framing, header compression, stream prioritization, and server push.

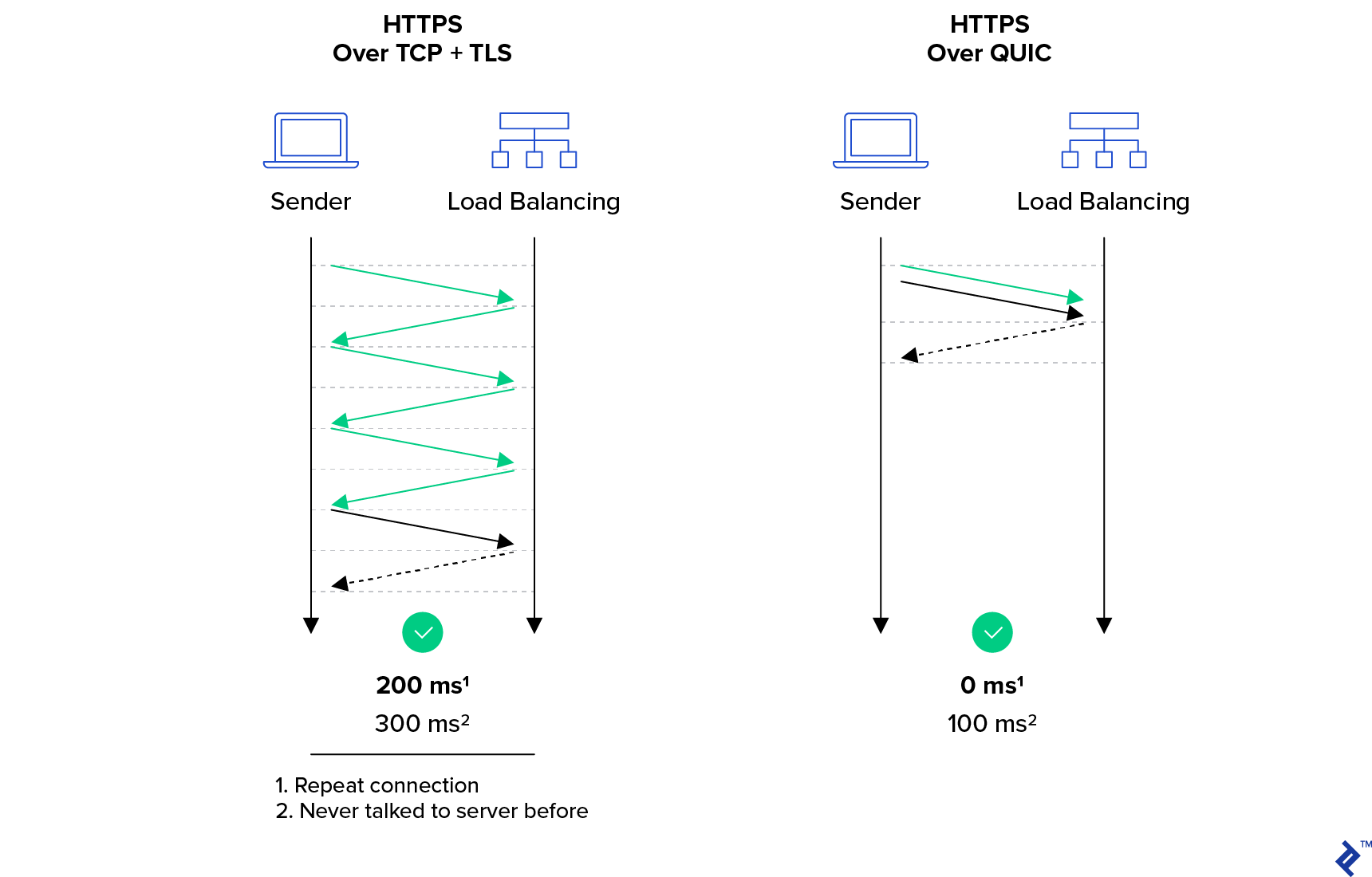

- HTTP/3 is even faster because it incorporates all of HTTP/2 and solves the TCP HOL blocking problem as well. HTTP/3 is still just a draft but is already being deployed. It is more efficient, uses fewer resources (system and network), requires encryption (SSL certificates are mandatory), and uses UDP.

- Although web browsers are likely to continue to support the older versions of HTTP for some time, performance benefits and prioritization of HTTP/3-savvy sites by search engines should drive adoption of the newer protocols.

- SPDY is obsolete and anyone using it should replace it with HTTP/2.

- Today's sites should already be supporting both HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2.

- In the near future, site owners will probably want to be supporting HTTP/3 as well. However, it's more controversial than HTTP/2, and we'll likely see a lot of larger networks simply blocking it instead of taking the time to deal with it.

Performance and Efficiency: The Core Issue

The goal of website and application development is user engagement. While some target a specific audience, many aim for maximum user reach, as a larger user base often translates to higher revenue.

A mere 100-millisecond delay in website load time can reduce conversion rates by 7 percent.

Akamai Online Retail Performance Report: Milliseconds Are Critical (2017)

To illustrate, an eCommerce platform with daily sales of $40,000 could lose a million dollars annually due to such a delay.

It’s well known that a website’s performance is crucial for its popularity. Studies on online shopping behavior continues to find links between increased bounce rates and longer loading times, and between shopper loyalty and website performance during the shopping experience underscore this:

Research findings also found that:

- 47% of consumers anticipate web pages to load within 2 seconds.

- 40% abandon websites that take longer than 3 seconds to load.

And this was the state of online shopper patience over a decade ago. Thus, performance is paramount, and both HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 contribute to better website performance.

A Quick Look at HTTP/2

A solid grasp of HTTP/2 is essential for understanding HTTP/3. Why was there a need for HTTP/2 in the first place?

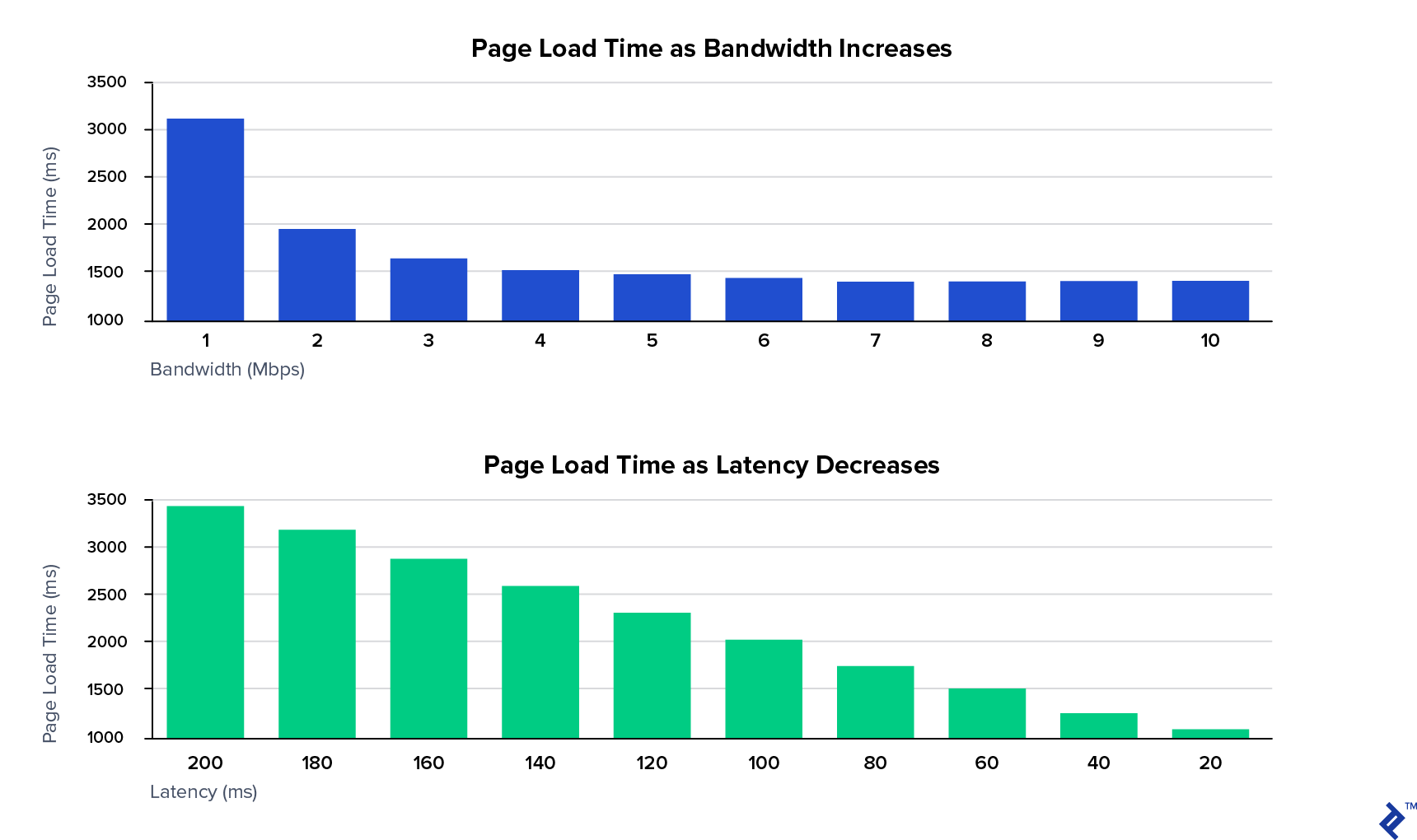

HTTP/2 originated as SPDY, a Google project that emerged from a study identifying latency as the primary web performance bottleneck. The study concluded that simply having “more bandwidth doesn’t matter (much)”:

Consider the analogy of plumbing and the Internet. Bandwidth can be compared to the diameter of a water pipe. A wider pipe carries more water, enabling faster water transfer between two points.

However, regardless of the pipe’s size, if it’s empty and water needs to travel from one end to the other, it takes time. This time, in Internet terms, is called the round trip time or RTT.

The study focused on reducing page load time. While increasing bandwidth initially helps (e.g., doubling bandwidth from 1 Mbps to 2 Mbps halves load time), the benefits quickly plateau.

Conversely, reducing latency provides consistent benefits and yields the best outcomes.

HTTP HOL: The Head-of-line Blocking Issue

The primary latency culprit in HTTP/1 is the head-of-line blocking problem. Web pages usually require multiple resources: CSS, JavaScript, fonts, images, AJAX/XMR, etc., necessitating multiple browser requests to the server. However, not all resources are essential for initial page usability.

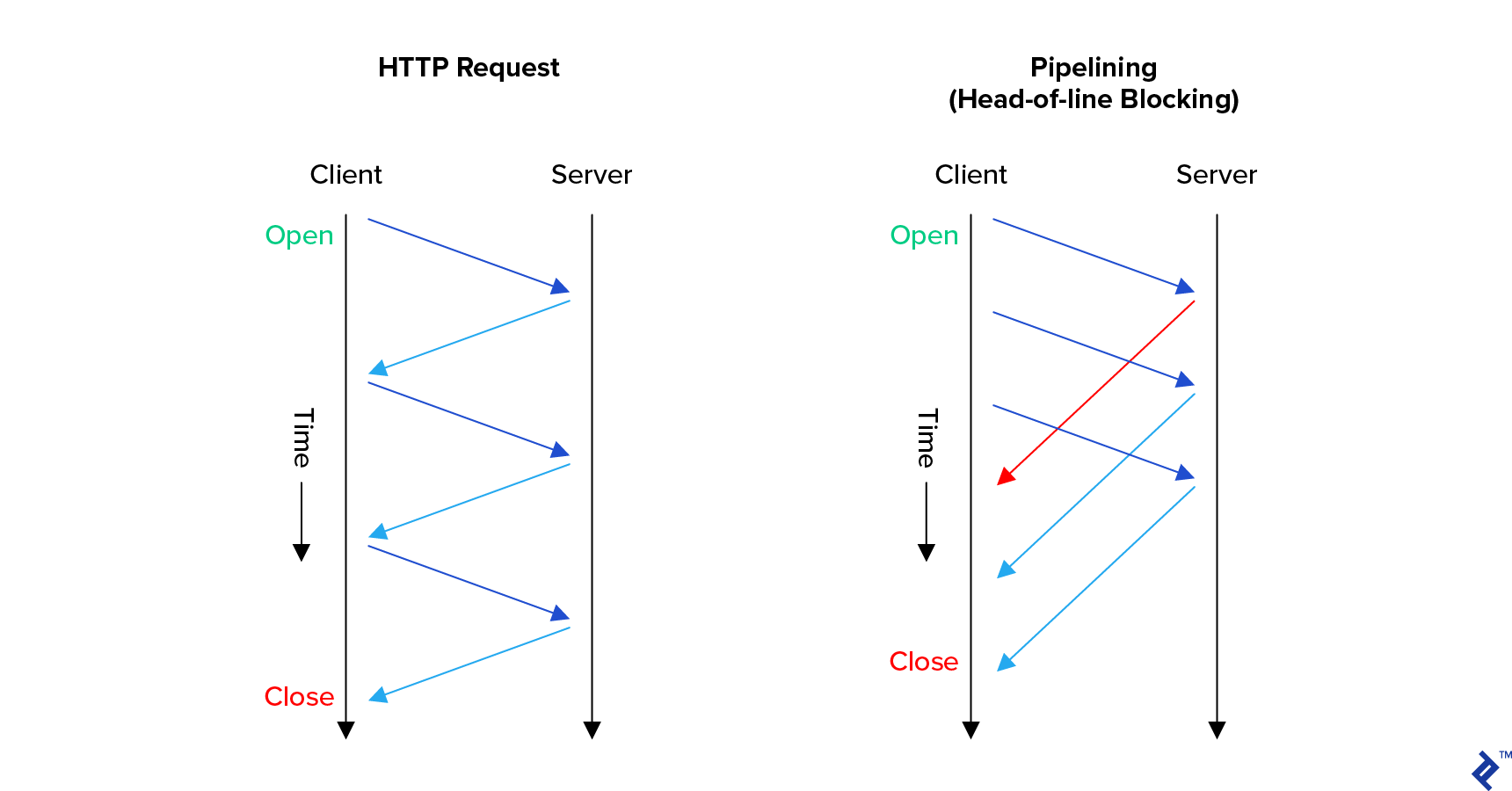

HTTP/1.0 required the browser to fully complete a request, including receiving the entire response, before initiating the next. Requests had to be processed sequentially, with each request blocking subsequent ones, hence the name.

To circumvent HOL blocking, browsers make multiple simultaneous connections to a server. However, excessive connections can overload servers, workstations, and networks, limiting this approach.

HTTP/1.1 introduced improvements, notably pipelining, allowing browsers to initiate new requests without waiting for previous ones to finish. This significantly improved loading times in low-latency environments.

However, responses still arrived sequentially, maintaining the head-of-line blocking issue. Surprisingly, many servers still don’t utilize pipelining.

Interestingly, HTTP/1.1 also introduced keep-alive, aiming to reduce overhead by reusing TCP connections for multiple HTTP requests. However, this attempt to address a TCP-related performance issue proved ineffective, with many experts advising against it due to server bogging from inactive connections. We’ll delve deeper into TCP and its resolution in HTTP/2 later.

HTTP/2’s Solution to HTTP HOL Blocking

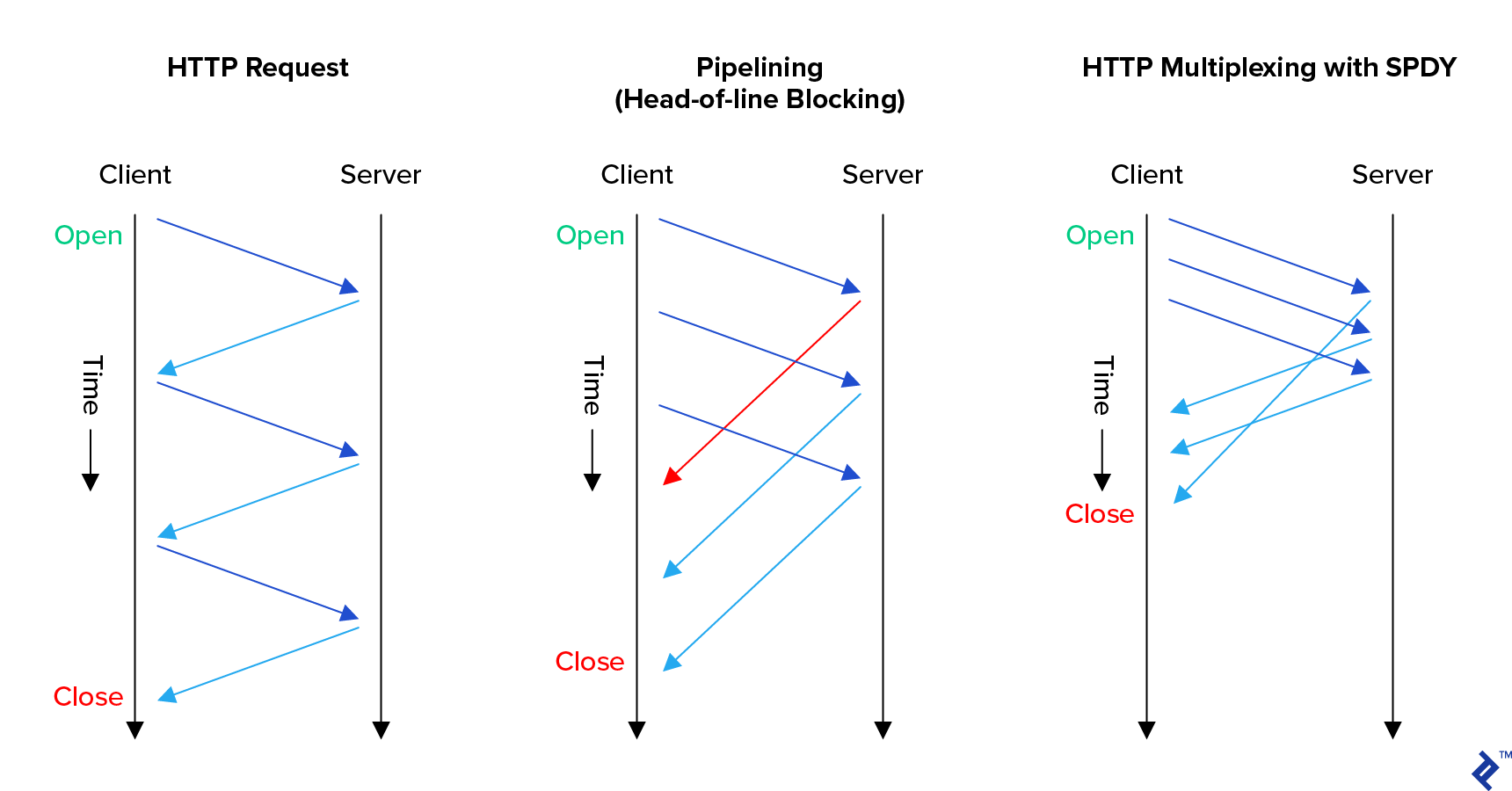

HTTP/2 introduced request-response multiplexing over a single connection. Browsers can not only initiate new requests anytime but also receive responses out of order, eliminating blocking at the application level.

This empowers HTTP/2-aware servers to maximize efficiency, as we’ll explore further.

While multiplexing is a key feature, HTTP/2 boasts other significant improvements, all interconnected.

HTTP/2 Binary Framing

HTTP/2 transitions from an inefficient human-readable ASCII request-response model to a streamlined binary framing approach. Communication is no longer limited to simple requests and responses:

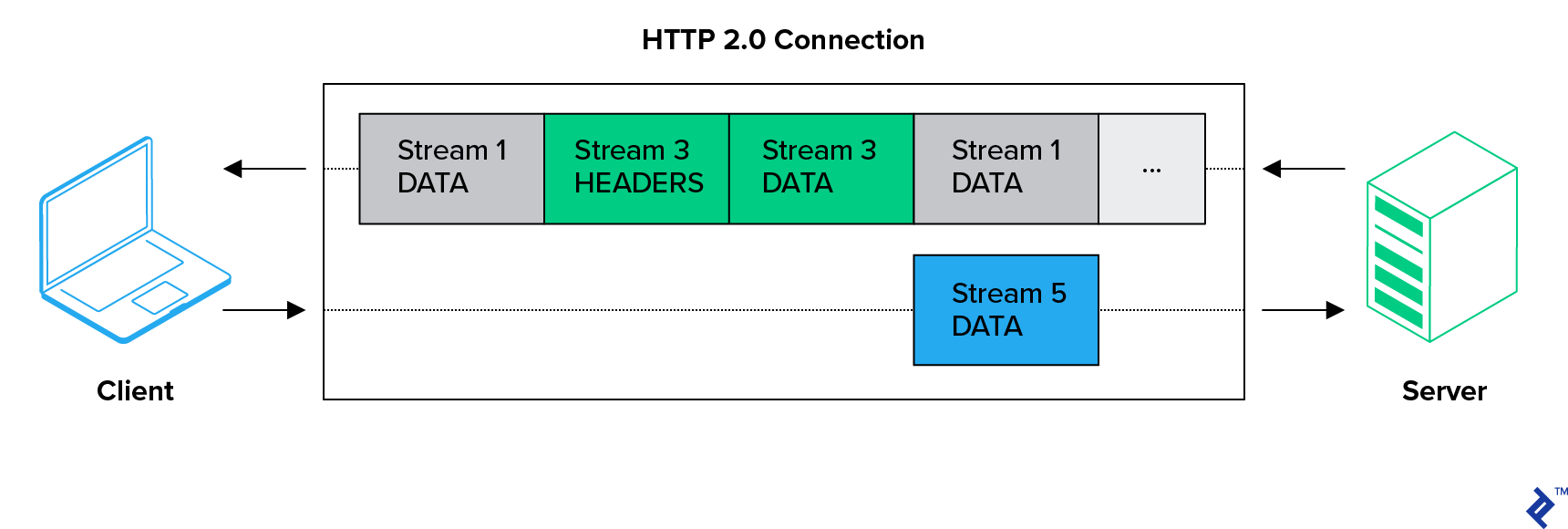

In HTTP/2, browsers and servers communicate over bidirectional streams containing multiple messages, each composed of multiple frames.

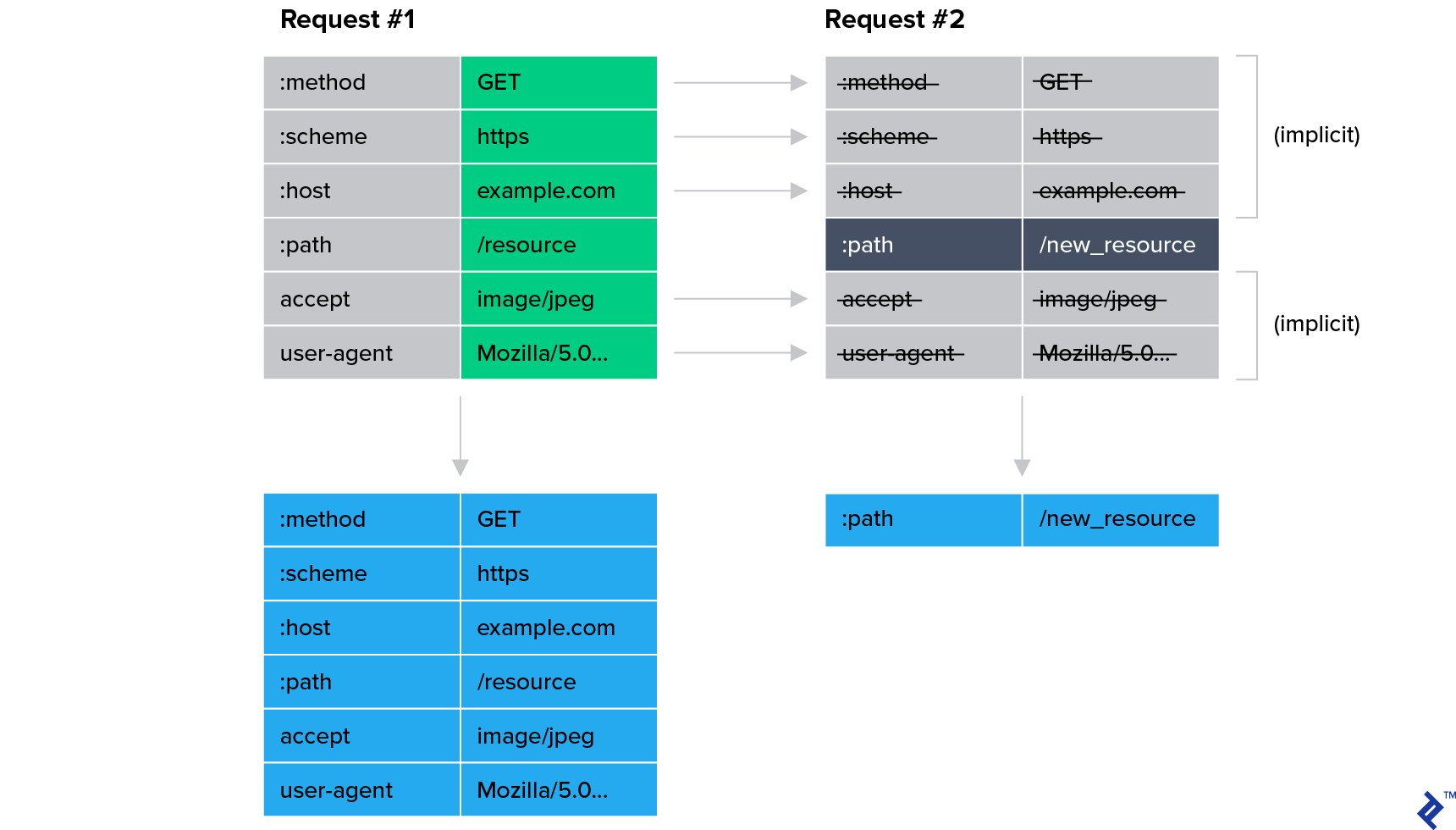

HTTP/2 HPACK (Header Compression)

Header compression using the HPACK format in HTTP/2 significantly reduces bandwidth consumption for most websites. This is because a majority of headers within a connection are identical.

Cloudflare reports substantial bandwidth savings thanks to HPACK alone:

- 76% compression for incoming headers

- 53% reduction in total incoming traffic

- 69% compression for outgoing headers

- 1.4% to 15% reduction in total outgoing traffic

Reduced bandwidth generally translates to faster websites.

HTTP/2 Stream Prioritization and Server Push

Multiplexing in HTTP/2 enables servers to maximize efficiency. While it facilitates faster delivery of readily available resources (e.g., cached JavaScript) before slower ones (e.g., large images, dynamically generated JSON), it also unlocks further performance enhancements through stream prioritization.

Stream prioritization ensures that nearly complete page elements are fully loaded without waiting for resource-intensive requests. This is achieved through a weighted dependency tree, guiding the server on resource allocation for serving responses.

This is particularly crucial for progressive web applications (PWAs). For instance, consider a page with four JavaScript files: two for functionality and two for ads. The worst-case scenario involves loading parts of both functional and ad-related JavaScript, followed by large images, before loading the remaining JavaScript. This leads to initial page dysfunction, as everything waits for the slowest resource.

With stream prioritization, browsers instruct the server to prioritize both functional JavaScript files, ensuring user interaction without waiting for ads to fully load. While the overall loading time may not improve, the perceived performance significantly increases. However, this browser behavior relies heavily on algorithms rather than developer-specified instructions.

Similarly, HTTP/2’s server push allows servers to proactively send resources to the browser before it requests them. This efficient bandwidth utilization preloads resources the server anticipates the browser will need soon. The goal is to eliminate resource inlining, which bloats resources and increases loading times.

However, both features require careful developer configuration for optimal results. Simply enabling them isn’t enough.

HTTP/2 offers numerous potential benefits, some easier to implement than others. But how has it fared in practice?

Adoption of HTTP vs HTTP/2

SPDY emerged in 2009, while HTTP/2 was standardized in 2015. SPDY became an unstable development branch, with HTTP/2 as the final version. Consequently, SPDY became obsolete, and HTTP/2 is now the widely adopted standard.

Post-standardization, HTTP/2 (or “h2”) adoption surged to around 40% of the top 1,000 websites, primarily driven by large hosting and cloud providers implementing support for their customers. However, adoption has since plateaued, and the majority of the internet still relies on HTTP/1.

Browser Support for HTTP/2 Clear Text Mode: A Missing Piece

Many advocated for mandatory encryption in HTTP/2. However, the standard defined both encrypted (h2) and clear text (h2c) modes, potentially allowing HTTP/2 to fully replace HTTP/1.

Despite this, current browsers solely support HTTP/2 over encrypted connections, intentionally omitting clear text mode. Instead, they rely on HTTP/1 backward compatibility for insecure servers. This stems from the push for a secure web by default.

HTTP/3: Rationale and Distinctions

With HTTP’s head-of-line blocking addressed by HTTP/2, focus shifted to the next major latency contributor: the TCP head-of-line blocking problem.

Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) Explained

IP (internet protocol) networks rely on computers exchanging packets, which are essentially data units with addressing information.

However, applications often require streams of data. To ensure this illusion, the transmission control protocol (TCP) provides applications with a pipe for data flow, guaranteeing “first in, first out” (FIFO) order. These characteristics have made TCP widely used.

TCP’s data delivery guarantees necessitate handling diverse situations. One complex issue is maintaining data flow during network overload without exacerbating the problem. The congestion control algorithm, a continuously evolving internet specification, addresses this. Insufficient congestion control can cripple the internet.

In October 1986, the Internet experienced its first “congestion collapse.” Data throughput between LBL and UC Berkeley (separated by 400 yards and three network hops) plummeted from 32 Kbps to a mere 40 bps.

This is where the TCP head-of-line blocking problem arises.

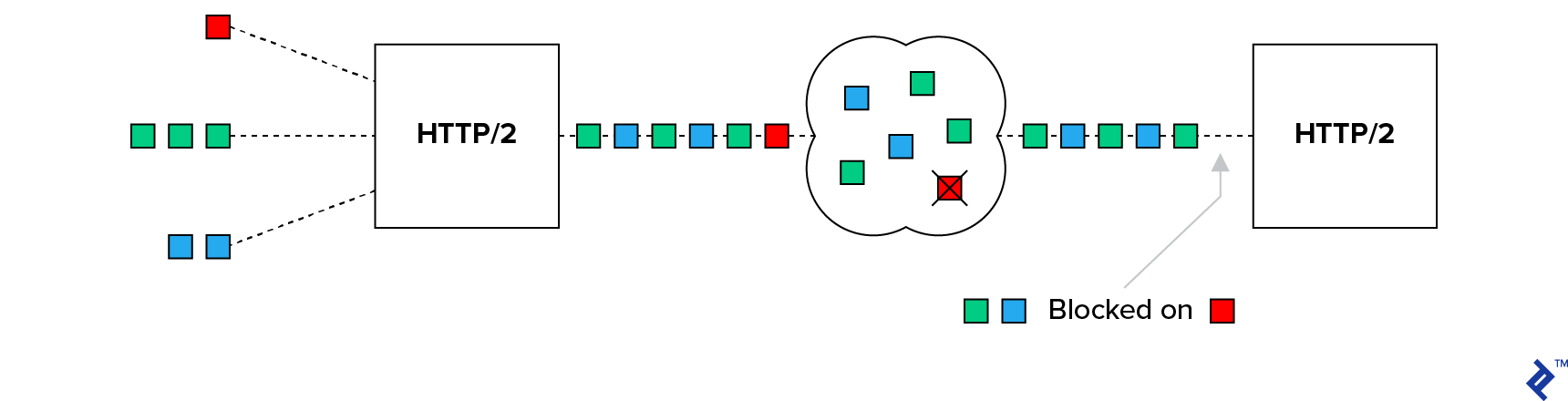

TCP HOL Blocking: The Problem

TCP congestion control utilizes backoff and retransmission mechanisms for packets when loss is detected. Backoff alleviates network congestion, while retransmission ensures eventual data delivery.

However, TCP data can arrive out of order, requiring the receiver to reorder packets before reassembly. Unfortunately, a single lost packet can stall the entire TCP stream, blocking the head of the line.

Google tackled this issue by introducing a protocol called QUIC.

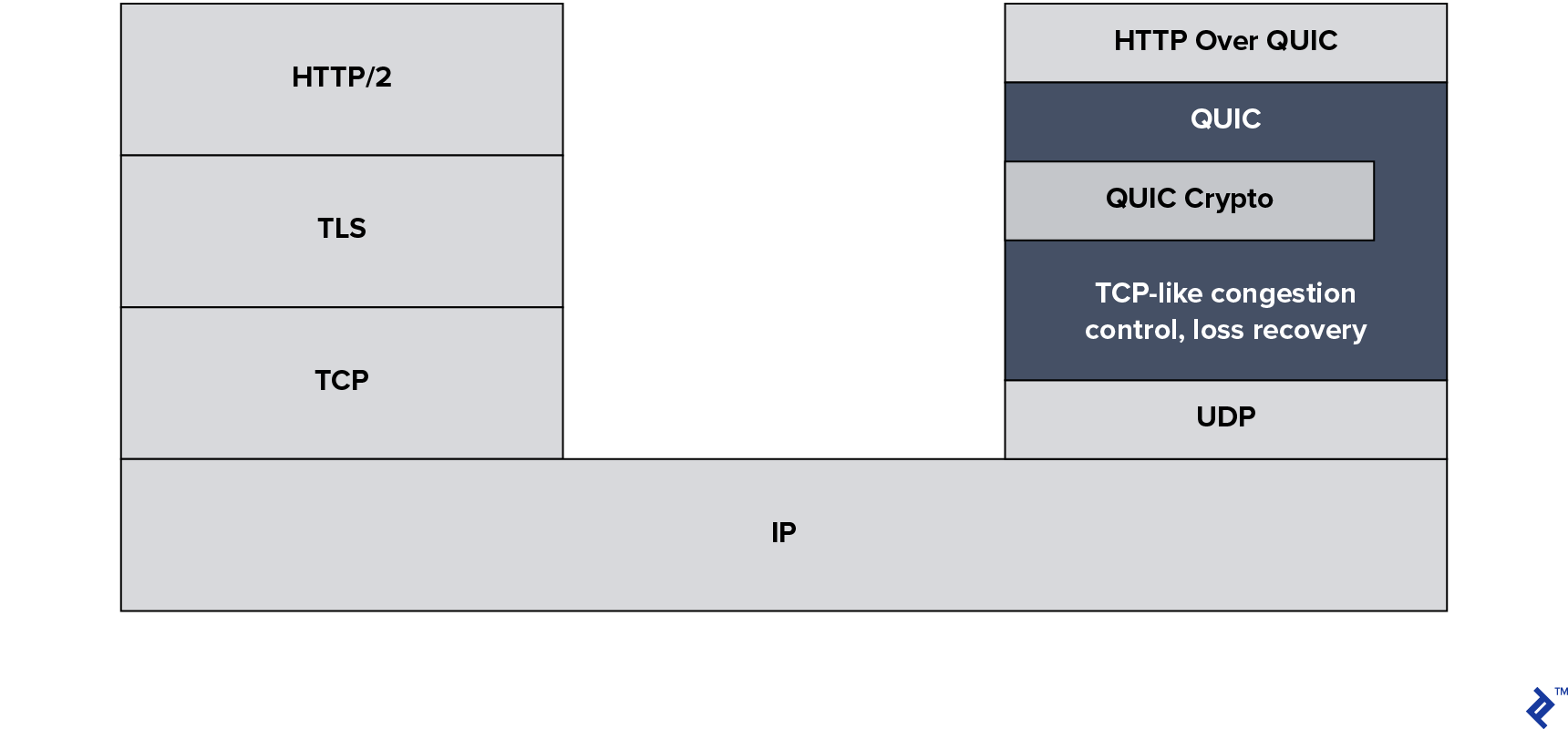

The QUIC protocol, built on UDP instead of TCP, forms the foundation of HTTP/3.

Understanding UDP

The user datagram protocol (UDP) offers an alternative to TCP. It doesn’t provide the illusion of a stream or TCP’s guarantees. Instead, it simply facilitates placing data into packets, addressing them, and sending them. It’s unreliable, unordered, and lacks congestion control.

UDP prioritizes lightweight communication with minimal features, allowing applications to implement their own guarantees. This is beneficial for real-time applications like phone calls, where receiving 90% of data immediately is preferable to receiving 100% eventually.

HTTP/3’s Solution to TCP HOL Blocking

Switching to UDP alone doesn’t solve the TCP HOL blocking problem. Ensuring data delivery and preventing network congestion collapse are crucial. QUIC achieves this by providing an optimized HTTP over UDP experience.

With QUIC managing stream management, binary framing, etc., HTTP/2’s role atop QUIC diminishes. This drives the standardization of QUIC + HTTP as HTTP/3.

Note: QUIC has multiple versions due to its ongoing development and production deployment, including a Google-specific version called GQUIC. It’s important to distinguish between older QUIC protocols and the new HTTP/3 standard.

Always Encrypted

HTTP/3 incorporates encryption inspired by TLS but doesn’t directly use it. One implementation challenge involves modifying TLS/SSL libraries to accommodate new functionalities.

Unlike HTTPS, which only protects data with TLS, leaving transport metadata visible, HTTP/3 secures both data and the transport protocol. While enhancing security, this also improves performance by minimizing HTTP/2’s overhead.

HTTP/3’s Impact on Networking Infrastructure

HTTP/3 isn’t without its critics, primarily concerning its impact on networking infrastructure.

Client-Side Implications

Client-side UDP traffic often faces rate limiting and blocking, rendering HTTP/3 ineffective.

Furthermore, HTTP monitoring and interception are common. Even with HTTPS, networks analyze clear text transport elements to enforce website access restrictions based on network or region. Some countries even mandate this for service providers. HTTP/3’s mandatory encryption makes this impossible.

This extends beyond government-level filtering. Universities, libraries, schools, and homes with parental controls often block or log website access, which HTTP/3’s encryption hinders.

Limited filtering is currently possible using the unencrypted server name indication (SNI) field containing the hostname. However, the introduction of ESNI (encrypted SNI) in the TLS standard will soon change this.

Server-Side Implications

Best practices dictate blocking traffic on unused ports and protocols, requiring administrators to open UDP 443 for HTTP/3 instead of relying on existing TCP 443 rules.

Network infrastructure can make TCP sessions sticky, routing them to the same server despite changing priorities. HTTP/3’s use of sessionless UDP necessitates infrastructure updates to track unencrypted HTTP/3-specific connection IDs for sticky routing.

HTTP inspection for abuse detection, security monitoring, and malware prevention is common but impossible with HTTP/3’s encryption. However, options with shared security keys are possible if devices support HTTP/3.

Lastly, managing more SSL certificates is a concern for administrators, although services like Let’s Encrypt alleviate this.

Widespread HTTP/3 adoption might be hindered until widely accepted solutions address these concerns.

Web Development: The Impact of HTTP/3

There’s little to worry about on the web development front. HTTP/2’s stream prioritization and server push are present in HTTP/3. Developers should get familiar with these features for optimal site performance.

Utilizing HTTP/3 Today

Google Chrome and Chromium users are already equipped for HTTP/3. While production-ready HTTP/3 servers are still in development—the specification is not yet finalized—tools for experimentation are available. Google and Cloudflare have already implemented support in their production environments.

Using Caddy in Docker provides the simplest way to try it out. You’ll need an SSL certificate and a publicly accessible IP address. The steps are:

- DNS configuration. Set up a live hostname, e.g.,

yourhostname.example.com IN A 192.0.2.1. - Caddyfile creation. Include these lines:

| |

- Caddy execution: Run

docker run -v Caddyfile:/etc/Caddyfile -p 80:80 -p 443:443 abiosoft/caddy --quicor, if outside Docker, usecaddy --quic. - Chromium with QUIC: Launch Chromium with

chromium --enable-quic. - (Optional) Install a Protocol Indicator extension.

- Access the QUIC-enabled server, where you should see a file browser.

Developers can test their servers using these helpful tools:

- Keycdn’s HTTP/2 Test

- LiteSpeed’s HTTP3Check

- Qualys’ SSL Server Test

Thank you for reading!